Advanced Strategies for Troubleshooting Poor Drug Solubility in Formulation Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the pervasive challenge of poor aqueous solubility, which affects up to 90% of new drug candidates.

Advanced Strategies for Troubleshooting Poor Drug Solubility in Formulation Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals tackling the pervasive challenge of poor aqueous solubility, which affects up to 90% of new drug candidates. It explores the foundational principles of solubility and the Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS), details established and emerging methodological approaches from particle size reduction to lipid-based formulations, and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies for common technical hurdles. Furthermore, it examines advanced validation techniques, including machine learning and Quality by Design (QbD), and provides a comparative analysis of technologies to guide strategic formulation selection for improved bioavailability and clinical success.

Understanding the Solubility Challenge: Scope, Classification, and Impact on Bioavailability

Quantifying the Problem: Poor Solubility in Drug Development

The high prevalence of poorly water-soluble compounds is one of the most significant challenges in modern pharmaceutical development. The following table summarizes key quantitative data on this issue:

Table 1: Prevalence and Impact of Poorly Soluble Drugs

| Metric | Prevalence | Source/Note |

|---|---|---|

| New Chemical Entities (NCEs) | >70% are poorly water-soluble [1] | A leading factor in formulation challenges. |

| Drugs in Discovery Pipeline | Nearly 90% [2] [3] | Majority of molecules in development. |

| Approved Drugs on Market | ~40% [2] [4] | A significant portion of existing medicines. |

| BCS Class II & IV Drugs | >80% of NCEs [3] | BCS II (low solubility, high permeability); BCS IV (low solubility, low permeability). |

This widespread issue directly impacts a drug's bioavailability, which is the proportion of a drug that enters systemic circulation unaltered and can have a pharmacological effect [3]. For oral dosage forms, which constitute over 50% of all pharmaceutical formulations, poor aqueous solubility is a frequent barrier to achieving adequate bioavailability, often rendering drugs ineffective [5] [1].

Troubleshooting Guide: Addressing Common Solubility Challenges

This section provides a question-and-answer format to address specific, frequently encountered problems in pre-formulation and development.

FAQ: Pre-formulation and Strategy

Q1: My new chemical entity (NCE) has extremely low aqueous solubility. What is the first scientific approach I should take?

A: Begin by thoroughly characterizing your compound's physicochemical properties. Key factors affecting solubility include:

- pH and pKa: For ionizable compounds, solubility is highly pH-dependent. Weakly acidic drugs are more soluble at pH > pKa, while weakly basic drugs are more soluble at pH < pKa [2]. Determining the pKa is essential for considering salt formation.

- Polarity: A drug must be lipid-soluble to pass through membranes for absorption but require some aqueous solubility for dissolution. The lipid-water partition coefficient (Log P) is a critical parameter to measure [5].

- Solid-State Properties: Investigate the melting point and crystallinity. High-melting, highly crystalline "brick dust" compounds are often challenging [3] [6].

Q2: How do I select the right bioavailability enhancement technology for my compound?

A: The selection is guided by the compound's properties within the Biopharmaceutical Classification System (BCS) and the underlying reason for poor bioavailability. The following workflow diagram outlines a logical decision-making process:

FAQ: Technical and Manufacturing Issues

Q3: I am developing an Amorphous Solid Dispersion (ASD) via spray drying, but my API has low solubility in preferred organic solvents like methanol and acetone. What can I do?

A: This is a common problem with high-melting point "brick dust" compounds [6]. Two advanced solutions are:

- Temperature Shift Process: Use an inline heat exchanger to rapidly heat the API-polymer slurry to a temperature above the solvent's boiling point immediately before atomization. This can achieve an 8- to 14-fold increase in dissolved API concentration, dramatically improving throughput [6].

- Volatile Processing Aids: For ionizable compounds, add a volatile acid (e.g., acetic acid for basic drugs) or base (e.g., ammonia for acidic drugs) to the solvent system to ionize and dissolve the API. The aid is removed during spray drying, regenerating the native API form in the amorphous dispersion [6].

Q4: During tablet compression, my tablets are exhibiting capping and lamination. Could this be related to the solubility-enhancing formulation?

A: Yes. These defects are often related to the formulation's properties and process parameters [7].

- Possible Reasons:

- Too many fine particles in the granulate, which can trap air.

- Not enough or an inefficient binder, leading to weak tablet structure.

- Compression force is too high.

- The speed of the tablet press is too high, not allowing time for entrapped air to escape.

- Solutions:

- Optimize the particle size distribution of the granulate.

- Use a sufficient quantity of an efficient binding agent.

- Adjust the compression force and use pre-compression.

- Decrease the speed of the tablet press to extend dwell time [7].

Q5: The dissolution rate of my final tablet is prolonged and out of specification. How can I troubleshoot this?

A: This is often a formulation-related issue [7].

- Possible Reasons:

- Too much binder used, forming a too-dense matrix.

- No disintegrant or an inefficient disintegrant is present in the formulation.

- The compression force used was too hard, reducing porosity.

- Solutions:

- Reduce the amount of binder in the formulation.

- Incorporate a disintegrant or superdisintegrant.

- Decrease the compression force during tableting [7].

Experimental Protocols for Key Solubility Enhancement Techniques

Protocol: Formulation Screening for Amorphous Solid Dispersions (ASD)

Objective: To create and screen amorphous solid dispersions for a poorly water-soluble API to enhance solubility and dissolution rate.

Materials:

- API: Poorly water-soluble drug compound.

- Polymers: e.g., HPMC (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose), HPMCAS (hydroxypropyl methylcellulose acetate succinate), PVP-VA (polyvinylpyrrolidone-vinyl acetate copolymer).

- Solvent: e.g., Acetone, Methanol, Dichloromethane (DCM).

- Equipment: Spray dryer or rotary evaporator, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD), dissolution apparatus.

Methodology:

- Solubility Parameter Screening: Use computational tools (e.g., via QM/MD modeling) or empirical methods to calculate the solubility parameters of the API and various polymers. Select polymer candidates with parameters closest to the API to maximize miscibility [3] [8].

- Solution Preparation: Prepare clear solutions of the API and polymer in a suitable organic solvent at a defined ratio (e.g., 10:90 to 50:50 API-to-polymer). For low-solubility compounds, apply heat or use volatile processing aids as described in FAQ #3 [6].

- ASD Formation:

- Spray Drying: Atomize the solution into a heated drying chamber. Collect the dried solid particles. Key parameters: inlet temperature, feed rate, atomization pressure [6].

- Hot-Melt Extrusion: Physically mix the API and polymer and feed into a heated extruder. The intense mixing and thermal energy dissolve the API into the polymer melt. Key parameters: barrel temperature profile, screw speed, screw configuration [5] [3].

- Solid-State Characterization:

- Use DSC to confirm the absence of the API's crystalline melting point, indicating amorphization.

- Use XRPD to verify the crystalline API has been converted to an amorphous state (shown by a halo pattern instead of sharp peaks).

- In-Vitro Performance Testing:

- Conduct dissolution studies under physiologically relevant conditions (e.g., pH 1.2, 4.5, 6.8) and compare the dissolution profile against the pure crystalline API.

Protocol: Production of Drug Nanocrystals via Nano-Milling

Objective: To reduce the particle size of a poorly soluble crystalline drug to the nanoscale to increase surface area and dissolution rate.

Materials:

- API: Poorly water-soluble drug compound.

- Stabilizers: Surfactants (e.g., polysorbates, sodium lauryl sulfate) or polymers (e.g., HPC, PVP).

- Milling Media: e.g., Zirconia or glass beads (0.1-1.0 mm).

- Equipment: Wet bead mill or high-pressure homogenizer.

Methodology:

- Suspension Preparation: Create a pre-suspension by dispersing the coarse API powder in an aqueous solution containing stabilizers.

- Nano-Milling:

- Wet Bead Milling: Charge the milling chamber with milling media and the pre-suspension. Mill for a predetermined cycle time. The intense shear forces from bead collisions fracture the drug particles. Key parameters: bead size, milling speed, milling time, and temperature control [1].

- High-Pressure Homogenization: Alternatively, pass the pre-suspension through a high-pressure homogenizer for multiple cycles to achieve particle size reduction via shear, cavitation, and collision [1].

- Separation and Recovery: Separate the nanocrystal suspension from the milling beads using a sieve.

- Characterization:

- Particle Size Analysis: Use dynamic light scattering (DLS) or laser diffraction to determine the mean particle size (Z-average) and particle size distribution (PDI). The target is typically a mean particle size below 1 μm [5].

- Dissolution Testing: Perform a dissolution test and compare the rate and extent of release against the unmilled API.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Solubility Enhancement Formulations

| Category | Item | Function in Experiment | Example Uses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polymers for ASDs | HPMC (Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose) | Matrix former; inhibits crystallization and stabilizes the amorphous form. | Spray drying, hot-melt extrusion [1]. |

| PVP-VA (Polyvinylpyrrolidone-Vinyl Acetate) | Matrix former; enhances dissolution and maintains supersaturation. | Melt extrusion (e.g., in NORVIR) [1]. | |

| HPMCAS (HPMC Acetate Succinate) | pH-dependent polymer; dissolves in intestinal pH, preventing precipitation. | Spray drying for enteric protection [1]. | |

| Lipid-Based Carriers | Medium-Chain Triglycerides (MCT Oil) | Lipid vehicle; enhances solubility of lipophilic drugs and promotes absorption. | Self-emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems (SEDDS) [4]. |

| Surfactants (e.g., Polysorbate 80) | Emulsifier; lowers interfacial tension, aiding in emulsion and micelle formation. | SEDDS, SMEDDS, and nanoemulsions [5] [4]. | |

| Co-solvents (e.g., PEG 400) | Solubilizer; increases drug solubility in liquid formulations. | Liquid oral and parenteral formulations [5] [3]. | |

| Other Carriers & Agents | Cyclodextrins | Complexation agent; forms inclusion complexes to hide hydrophobic drug moieties. | Oral and injectable formulations [1] [4]. |

| Superdisintegrants (e.g., Croscarmellose Sodium) | Disintegrant; swells rapidly in water, breaking tablets apart to increase surface area. | Immediate-release tablets for poorly soluble drugs [7]. | |

| Processing Aids | Volatile Acids/Bases (e.g., Acetic Acid, Ammonia) | Temporary ionizer; increases API solubility in organic solvents during processing. | Spray drying of ionizable "brick dust" compounds [6]. |

| 5-O-(E)-p-Coumaroylquinic acid | 3-p-Coumaroylquinic Acid|For Research | Bench Chemicals | |

| [D-Pro4,D-Trp7,9,Nle11] Substance P (4-11) | [D-Pro4,D-Trp7,9,Nle11] Substance P (4-11), CAS:89430-34-2, MF:C58H77N13O10, MW:1116.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

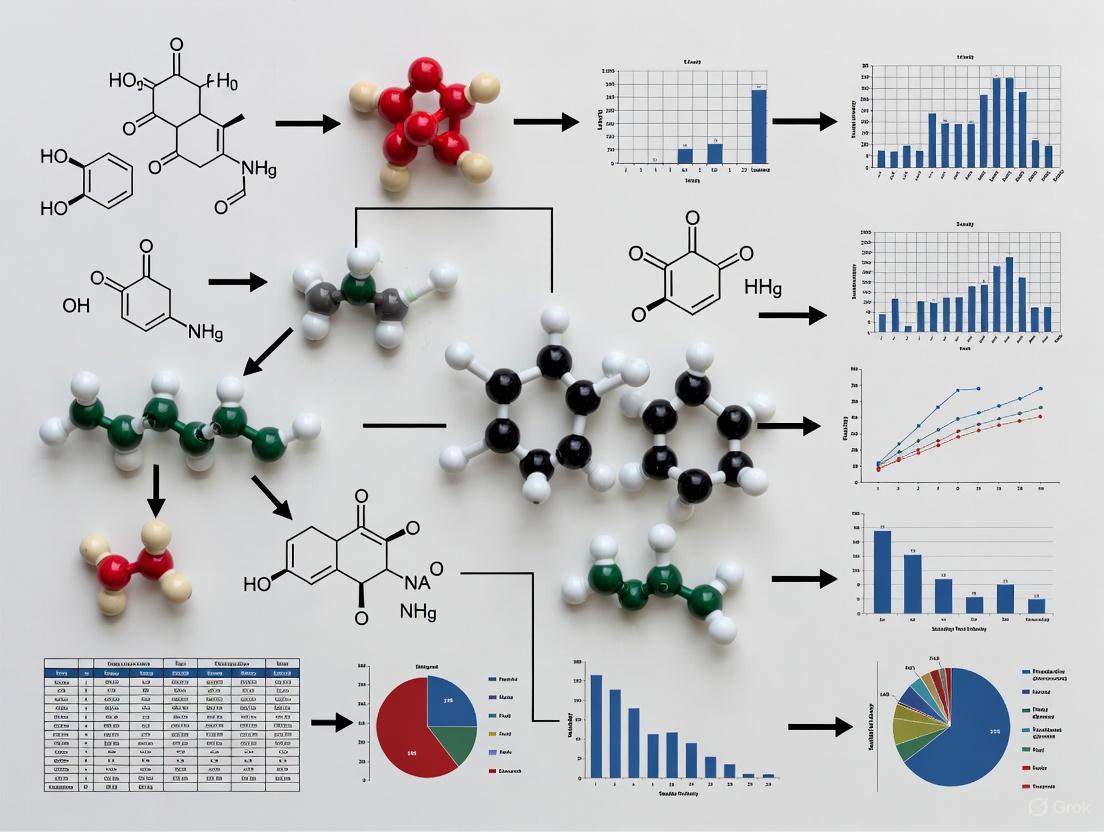

Workflow Visualization: Spray Drying with Temperature Shift

For compounds with poor organic solubility, the standard spray drying process must be modified. The following diagram illustrates the "Temperature Shift" method:

FAQ 1: What fundamentally distinguishes BCS Class II from Class IV drugs?

The core distinction lies in their permeability.

Both BCS Class II and IV drugs share the challenge of low solubility, meaning the highest dose strength does not dissolve in 250 mL or less of aqueous media over a pH range of 1 to 6.8 (or 7.5, depending on the guideline) [9] [10] [11]. However, their absorption pathways differ significantly:

- BCS Class II: High Permeability, Low Solubility. Once dissolved, these drugs are well-absorbed (human absorption extent is ≥ 85% or 90%) because they can easily cross the intestinal membrane. Their bioavailability is primarily limited by their dissolution rate in the gastrointestinal fluids [9] [12] [13].

- BCS Class IV: Low Permeability, Low Solubility. These drugs face a dual challenge. Even if they dissolve, their ability to permeate the intestinal lining is poor (human absorption extent is < 85% or 90%). This results in very low and variable bioavailability [10] [14].

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of all BCS classes for a comprehensive overview.

Table 1: Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Drug Classes

| BCS Class | Solubility | Permeability | Key Characteristics & Absorption Challenge | Example Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Well-absorbed; absorption rate is typically higher than excretion [10]. | Metoprolol, Paracetamol [10] |

| Class II | Low | High | Solubility-limited absorption; high absorption number but low dissolution number [9]. | Carbamazepine, Naproxen, Glibenclamide [9] |

| Class III | High | Low | Permeability-limited absorption; drug solvates quickly but permeation is slow [10]. | Cimetidine [10] |

| Class IV | Low | Low | Poorly absorbed; low and variable bioavailability due to both solubility and permeability constraints [10] [14]. | Bifonazole, Itraconazole [10] [14] |

FAQ 2: What advanced techniques can overcome the solubility challenge for Class II drugs?

For BCS Class II drugs, the primary goal is to enhance solubility and dissolution rate to improve bioavailability. Advanced methods move beyond traditional particle size reduction (micronization) by manipulating the drug's solid-state form or creating novel delivery systems [9] [14].

Experimental Protocol: Preparation of Solid Dispersions via Hot-Melt Method This is a common technique to create amorphous solid dispersions, which can significantly enhance solubility.

- Objective: To disperse a poorly soluble drug within a hydrophilic polymer matrix to create a single-phase, amorphous system with improved dissolution properties.

- Materials:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) - BCS Class II drug (e.g., Itraconazole).

- Hydrophilic polymer carrier (e.g., Povidone, Polyethylene glycol).

- Surfactant (optional, e.g., Sodium Lauryl Sulfate).

- Procedure:

- Weighing: Accurately weigh the drug and the carrier polymer in a predetermined ratio.

- Melting: Heat the mixture directly in an inert container until both components melt. The temperature must be carefully controlled to avoid degradation.

- Rapid Cooling: With continuous stirring, rapidly cool the molten mixture using an ice bath. This quick solidification helps prevent the drug from recrystallizing, locking it in an amorphous state within the polymer matrix.

- Solidification & Milling: The solidified mass is crushed, pulverized, and sieved to obtain a uniform powder.

- Characterization: The final solid dispersion must be characterized using techniques like Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) and X-Ray Powder Diffraction (XRPD) to confirm the amorphous nature of the drug [9] [14].

Table 2: Advanced Solubility Enhancement Techniques for BCS Class II/IV Drugs

| Technique | Mechanism | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Nanoinization [9] [11] | Reduces particle size to 200-600 nm, dramatically increasing surface area for dissolution. | Prevents particle aggregation; requires stabilizers. |

| Pharmaceutical Cocrystals [14] | Forms a new crystalline structure with a coformer via non-covalent bonds, improving solubility without changing API's molecular structure. | Selects pharmaceutically acceptable coformers; ensures physical stability. |

| Lipid-Based Systems (e.g., SEDDS) [14] | Uses lipids and surfactants to solubilize the drug and form fine emulsions in the GI tract, facilitating absorption. | Optimizes surfactant concentration to avoid GI irritation; prevents drug precipitation. |

| Cyclodextrin Complexation [15] | Hydrophobic cavity of cyclodextrin molecules encapsulates drug molecules, increasing apparent aqueous solubility. | Considers the solubility-permeability trade-off, as complexation can reduce free drug available for absorption [15] [16]. |

This common experimental hurdle is often due to the solubility-permeability interplay [15] [16]. When solubility is increased using certain "solubility-enabling formulations," the apparent intestinal permeability of the drug may be inadvertently reduced.

- Mechanism: Intestinal permeability is partially determined by the drug's partition coefficient between the membrane and the aqueous GI milieu (( K_m )). Formulations that increase solubility by incorporating the drug into cyclodextrin complexes or surfactant micelles decrease the free fraction of the drug available to partition into the intestinal membrane. While the total dissolved drug concentration is high, the concentration gradient of the free, absorbable drug—the driving force for permeability—is lowered [15] [16].

- Illustrative Experiment: A mass transport model demonstrated that as the concentration of hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin (HPβCD) increases, the apparent solubility of progesterone rises, but its effective permeability (( P_{eff} )) decreases due to the reduction in free drug fraction [15].

The following diagram illustrates this critical trade-off, which is key to troubleshooting failed absorption experiments.

FAQ 4: What strategies can simultaneously address both solubility and permeability for Class IV drugs?

BCS Class IV drugs are the most challenging, requiring formulations that tackle both low solubility and low permeability.

- Supersaturating Drug Delivery Systems (SDDS): These systems, such as amorphous solid dispersions, create a high-energy, metastable state of the drug that generates a supersaturated solution in the GI tract. Unlike cyclodextrin or surfactant-based systems, supersaturation increases the free drug concentration, thereby enhancing the driving force for permeability and potentially overcoming the solubility-permeability trade-off [16].

- Permeation Enhancers: Incorporate excipients that temporarily and reversibly alter the integrity of the intestinal epithelium. These can increase paracellular transport or fluidize the cellular membrane for better transcellular uptake. Caution: Their safety and long-term effects require thorough investigation.

- Prodrug Strategy: Chemically modify the drug to improve its inherent physicochemical properties. A prodrug can be designed to have better solubility and/or permeability than the parent drug. Once absorbed, the prodrug is metabolized back to the active moiety within the body.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Solubility and Permeability Enhancement Experiments

| Research Reagent | Function in Formulation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophilic Polymers (Povidone, PEG) [9] | Carrier matrix in solid dispersions to inhibit crystallization and maintain drug in amorphous state. | Hot-melt method and solvent evaporation for solid dispersions. |

| Cyclodextrins (HPβCD, SBE-β-CD) [15] | Molecular encapsulation agent forming water-soluble inclusion complexes with hydrophobic drugs. | Enhancing solubility for pre-clinical toxicology studies; used in oral and parenteral formulations. |

| Lipids & Surfactants (in SEDDS) [14] | Formulate self-emulsifying systems that spontaneously form microemulsions in GI fluid, solubilizing the drug. | Delivery of lipophilic BCS Class II drugs like paclitaxel. |

| Coformers for Cocrystals (e.g., succinic acid, caffeine) [14] | A component that forms hydrogen bonds with the API to create a new crystal lattice with improved properties. | Cocrystallization to enhance solubility and stability of a poorly soluble API. |

| Permeation Enhancers (e.g., sodium caprate) | Temporarily and reversibly increase intestinal membrane permeability. | Formulation of BCS Class III/IV drugs to improve absorption. |

| Doxazosin D8 | Doxazosin D8, MF:C23H25N5O5, MW:459.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| 2-(Methyl-d3)phenol | 2-(Methyl-d3)phenol, MF:C7H8O, MW:111.16 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

FAQ 1: What are the primary physicochemical properties that dictate a drug candidate's solubility? The two most critical properties are Melting Point (MP) and the partition coefficient (logP). A high melting point indicates strong crystal lattice energy, making dissolution difficult. LogP measures lipophilicity; a very high value indicates poor aqueous solubility. These properties define the "Brick-Dust" (high MP, moderate logP) and "Grease-Ball" (low MP, high logP) molecule paradigms.

FAQ 2: My compound has poor solubility. How do I determine if it's a 'Brick-Dust' or 'Grease-Ball' molecule? Perform the following characterization:

- Determine Melting Point: Use Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC).

- Measure LogP/LogD: Use shake-flask or chromatographic methods (e.g., HPLC).

- Compare to Thresholds: Use the data to classify your molecule.

Table 1: Characteristic Properties of Brick-Dust vs. Grease-Ball Molecules

| Property | Brick-Dust Molecule | Grease-Ball Molecule | Typical Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Melting Point (°C) | > 200 | < 150 | 200 °C |

| LogP | Moderate (1-3) | High (> 3) | 3 |

| Solubility Limitation | Solid-state (crystal lattice) | Solvation (hydrophobicity) | - |

| Common Structural Traits | High aromaticity, H-bond donors/acceptors, planar structure | Aliphatic chains, few polar groups, flexible | - |

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Issue - Poor Aqueous Solubility in Early Discovery

- Problem: Low measured solubility in pH 7.4 buffer is hampering biological assays.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Measure LogD at pH 7.4: This is more relevant than logP for ionizable compounds. A logD7.4 > 3 suggests a Grease-Ball issue.

- Check Melting Point: If MP > 200°C, a Brick-Dust component is significant.

- Assess Ionizability: Check the pKa. If the compound is ionizable, solubility will be pH-dependent.

- Solutions:

- For Grease-Ball (High LogD): Use solubilizing agents like cyclodextrins or surfactants (e.g., 0.01% Tween-80) in the assay buffer.

- For Brick-Dust (High MP): Use co-solvents like DMSO (keep ≤1% final concentration) or employ a amorphous solid dispersion pre-screening method.

- For Ionizable Compounds: Adjust the buffer pH to favor the ionized state (e.g., pH < pKa for bases, pH > pKa for acids).

Experimental Protocol 1: Determination of Apparent Solubility via Shake-Flask Method

- Objective: To determine the equilibrium solubility of a compound in a specific buffer.

- Materials: Test compound, buffer (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline, pH 7.4), orbital shaker, water bath, HPLC system with UV detection.

- Procedure:

- Prepare a saturated solution by adding an excess of solid compound to 1-2 mL of buffer in a vial.

- Agitate the suspension for 24 hours at a constant temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C) using an orbital shaker.

- After 24 hours, centrifuge an aliquot at a high speed (e.g., 14,000 rpm) for 10 minutes to separate undissolved solid.

- Dilute the supernatant appropriately with a compatible solvent (e.g., methanol:water 1:1).

- Analyze the diluted sample by HPLC against a standard curve of known concentrations.

- Calculation: Apparent Solubility (µg/mL) = (Measured Concentration from HPLC) × (Dilution Factor).

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Issue - Failure in Formulation Development for Animal Dosing

- Problem: Unable to achieve sufficient exposure in pharmacokinetic studies due to precipitation upon dosing.

- Diagnosis Steps:

- Review Physicochemical Data: Confirm the molecule's classification using Table 1.

- Perform Solvent Screening: Test solubility in various pharmaceutically acceptable solvents and surfactants.

- Solutions:

- For Brick-Dust Molecules: Explore salt formation (for ionizable compounds) or prepare an amorphous solid dispersion (SDD) using spray drying.

- For Grease-Ball Molecules: Utilize lipid-based formulations (e.g., SEDDS - Self-Emulsifying Drug Delivery Systems) containing oils, surfactants, and co-solvents.

- For Mixed/Neutral Compounds: Consider complexation with cyclodextrins or use of nanocrystal suspensions.

Experimental Protocol 2: Screening for Lipid-Based Formulations (SEDDS)

- Objective: To identify a self-emulsifying formulation that solubilizes the drug and forms a fine emulsion upon aqueous dilution.

- Materials: Drug compound, oils (e.g., Labrafil M1944CS, Captex 355), surfactants (e.g., Kolliphor RH40, Tween 80), co-surfactants (e.g., PEG 400, Transcutol P), vortex mixer, stability chamber.

- Procedure:

- Select a range of oils, surfactants, and co-surfactants. Pre-solubilize the drug in each excipient to assess maximum solubility.

- Based on solubility data, create ternary phase diagrams with varying ratios of Oil:Surfactant:Co-surfactant.

- For each promising mixture, add an excess of the drug and vortex until dissolved/saturated.

- Dilute a small aliquot of the preconcentrate (e.g., 50 µL) in a relevant aqueous medium (e.g., 0.01N HCl, pH 6.8 buffer) under gentle agitation.

- Visually assess the emulsion for clarity, phase separation, or precipitation over 1-2 hours.

- Select the most robust formulations for further stability and in vivo testing.

Diagram: Solubility Troubleshooting Workflow

Solubility Problem-Solving Pathway

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Solubility and Formulation Screening

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation |

|---|---|

| Kolliphor P407 | A non-ionic surfactant used to enhance solubility of lipophilic compounds and form micelles. |

| Hydroxypropyl Betadex (HP-β-CD) | A cyclodextrin used to form inclusion complexes, improving the apparent solubility and stability of drugs. |

| Labrasol ALF | A non-ionic surfactant and co-surfactant commonly used in SEDDS formulations to aid self-emulsification. |

| Capmul MCM C8 | A medium-chain mono/diglyceride used as an oil phase in lipid-based formulations. |

| HPMC (Hypromellose) | A polymer used as a matrix carrier in amorphous solid dispersions to inhibit crystallization. |

| DMSO | A universal solvent for creating high-concentration stock solutions for in vitro assays (use with caution in vivo). |

| Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) | An ionic surfactant used in dissolution media to simulate sink conditions for poorly soluble drugs. |

| o-Toluic acid-13C | 2-Methylbenzoic Acid|Research Use |

| Glycolic acid-d2 | Glycolic acid-d2, CAS:75502-10-2, MF:C2H4O3, MW:78.06 g/mol |

In pharmaceutical development, solubility is a critical parameter that directly influences a drug candidate's absorption, bioavailability, and ultimate therapeutic efficacy. The distinction between thermodynamic and kinetic solubility represents a fundamental concept that formulation scientists must grasp to properly interpret data, troubleshoot formulation issues, and develop robust dosage forms. Thermodynamic solubility refers to the maximum concentration of a compound that can remain dissolved in a solution at equilibrium under specific temperature and pressure conditions, representing the genuine equilibrium solubility where the solid phase exists in equilibrium with the solution phase [17]. Conversely, kinetic solubility describes the concentration at which a compound initially dissolved in an organic solvent (typically DMSO) begins to precipitate when introduced into an aqueous medium, representing a metastable condition that can exceed the equilibrium solubility [17] [18]. This technical guide explores these critical distinctions through troubleshooting guides and FAQs designed to address specific experimental challenges in formulation research.

Core Concepts: Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Solubility

Fundamental Definitions and Distinctions

Thermodynamic Solubility represents the true equilibrium state where the chemical potential of the solid phase equals the chemical potential of the dissolved phase. It answers the question: "To what extent does the compound dissolve?" and is characterized by:

- Measurement starting from the solid compound

- Achievement of equilibrium between solid and dissolved phases

- Dependence on the solid-state form (crystalline, amorphous, polymorph)

- Relevance for formulation development and predicting in vivo behavior [17] [18] [19]

Kinetic Solubility describes a metastable state where precipitation from a supersaturated solution is measured. It answers the question: "To what extent does the compound precipitate?" and is characterized by:

- Measurement starting from a pre-dissolved compound in DMSO

- Assessment of precipitation behavior during dilution into aqueous media

- Higher apparent solubility values due to supersaturation

- Utility in early discovery for ranking compounds and guiding lead optimization [17] [18] [19]

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Thermodynamic vs. Kinetic Solubility

| Parameter | Thermodynamic Solubility | Kinetic Solubility |

|---|---|---|

| Starting Material | Solid compound | Pre-dissolved in DMSO |

| Equilibrium State | Achieved true equilibrium | Metastable, supersaturated state |

| Measurement Focus | Maximum dissolution capacity | Precipitation onset |

| Time Dependency | Requires longer equilibration (hours-days) | Rapid determination (minutes) |

| Solid-State Dependence | Highly dependent | Less dependent |

| Primary Application | Formulation development, IND submission | Early discovery, lead optimization |

| Typical Values | Generally lower | Often higher |

Experimental Workflows and Methodologies

The experimental approaches for determining thermodynamic and kinetic solubility follow distinct pathways with different critical steps and decision points, as illustrated below:

Diagram: Experimental workflows for thermodynamic (green) and kinetic (red) solubility determination

Thermodynamic Solubility Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Weigh an excess of solid compound into a suitable vessel

- Solvent Addition: Add aqueous buffer of known composition and pH

- Equilibration: Agitate at constant temperature (typically 25°C or 37°C) for 24-72 hours

- Phase Separation: Separate saturated solution from undissolved solid via filtration or centrifugation

- Analysis: Quantify drug concentration in supernatant using HPLC-UV or other suitable analytical method

- Solid-State Characterization: Analyze residual solid by XRPD to confirm no phase changes occurred [17] [19]

Kinetic Solubility Protocol:

- Stock Solution Preparation: Dissolve compound in DMSO to create concentrated stock (typically 10 mM)

- Serial Dilution: Prepare dilution series in aqueous buffer, maintaining constant DMSO concentration (usually <1%)

- Incubation: Allow solutions to equilibrate for short period (minutes to hours)

- Precipitation Detection: Monitor solutions for precipitation using nephelometry, UV turbidity, or visual inspection

- Concentration Measurement: Determine concentration at which precipitation begins via HPLC or direct UV measurement [18] [19]

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Experimental Challenges

Solubility Measurement Discrepancies

Problem: Significant differences observed between thermodynamic and kinetic solubility values for the same compound.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Verify Solid-State Stability: Characterize the pre- and post-equilibration solid material using XRPD. Solution-mediated phase transformation during thermodynamic measurement can convert metastable forms to more stable, less soluble forms, lowering apparent thermodynamic solubility [17].

- Assess Crystallinity: Amorphous materials typically show 1-3 orders of magnitude higher solubility than crystalline forms but are thermodynamically metastable. Kinetic measurements often reflect amorphous solubility, while thermodynamic measurements reflect crystalline form solubility [19].

- Check for Impurities: HPLC analysis during solubility measurement can detect impurities that might artificially inflate solubility values, particularly in UV-based methods [19].

- Evaluate Time Dependence: Ensure adequate equilibration time for thermodynamic measurements by sampling at multiple time points until concentration plateaus [17].

Solution: Document the solid-state form used in experiments and characterize residual material. Understand that kinetic solubility typically represents the amorphous form solubility, while thermodynamic solubility represents the crystalline form.

Unexpected Precipitation in Supersaturated Systems

Problem: Formulations maintaining high initial solubility but precipitating over time.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Identify Precipitation Triggers: Determine if precipitation results from pH changes, dilution, temperature fluctuations, or time-dependent crystallization [17].

- Monitor Supersaturation: Track concentration over time to establish supersaturation maintenance profile, similar to the dissolution curve shown in Figure 3 where amorphous form solubility drastically decreased after approximately 10 minutes due to spontaneous crystallization [17].

- Implement Precipitation Inhibitors: Incorporate polymers such as HPMC, PVP, or Soluplus that can inhibit crystallization and maintain supersaturation [6] [20].

- Optimize Formulation Approach: Consider amorphous solid dispersions, lipid-based systems, or nanosuspensions designed to maintain metastable supersaturation [6] [21] [20].

Solution: Develop formulations that create and maintain appropriate supersaturation levels using precipitation inhibitors tailored to the specific drug and administration route.

Poor Correlation Between Solubility and Bioavailability

Problem: Adequate solubility measurements not translating to acceptable in vivo performance.

Troubleshooting Steps:

- Evaluate Biorelevant Media: Measure solubility in simulated gastric and intestinal fluids rather than simple aqueous buffers to better predict in vivo behavior [18].

- Assess Permeability Limitations: Determine if poor bioavailability stems from solubility limitations or permeability issues using parallel permeability assessments [11].

- Investigate Precipitation Kinetics: Evaluate if rapid precipitation in the gastrointestinal tract reduces effective concentration available for absorption, requiring formulations that maintain supersaturation throughout the absorption window [17] [20].

- Consider Food Effects: Assess solubility under fed-state conditions that may differ significantly from fasted-state predictions [20].

Solution: Implement pH-dependent solubility testing, biorelevant media analysis, and permeation assays to develop a comprehensive biopharmaceutical profile [18].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: When should I use kinetic versus thermodynamic solubility measurements during drug development? A1: Kinetic solubility is ideal for early discovery stages (lead identification and optimization) where high-throughput compound ranking is needed, and material is often DMSO stocks. Thermodynamic solubility should be used during later preclinical development for formulation optimization, IND submission, and predicting in vivo behavior, as it reflects the equilibrium state of the solid dosage form [18] [19].

Q2: Why does my kinetic solubility value exceed my thermodynamic solubility value? A2: This expected difference occurs because kinetic solubility measures precipitation from a supersaturated solution, often reflecting the solubility of amorphous or high-energy forms. Thermodynamic solubility represents the stable crystalline form at equilibrium. Differences of 10-1000x are common, with larger gaps typically observed for compounds with high crystallinity [17] [19].

Q3: How long should I equilibrate samples for thermodynamic solubility measurements? A3: Equilibration times typically range from 24-72 hours, but should be determined experimentally by measuring concentration at multiple time points until no significant change occurs (<5% variation between consecutive time points). Verification beyond the equilibration time is recommended to confirm true equilibrium [17].

Q4: What solid-state characterization is essential for proper interpretation of thermodynamic solubility? A4: X-ray powder diffraction (XRPD) of the initial material and the residual solid after equilibration is crucial to confirm no phase transformations (polymorphic changes, hydrate formation, amorphization) occurred during measurement. Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) can provide complementary information about thermal properties [17] [19].

Q5: How can I improve solubility for poorly soluble compounds? A5: Multiple strategies exist, including:

- Physical Modifications: Particle size reduction (micronization, nanosuspension), crystal form modification (amorphous solid dispersions, polymorph selection)

- Chemical Modifications: Salt formation, prodrug approaches, co-crystallization

- Formulation Approaches: Lipid-based systems, complexation with cyclodextrins, use of surfactants and cosolvents [6] [11] [21]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Solubility Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function & Application | Examples & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| DMSO | Solvent for stock solutions in kinetic solubility studies | Maintain concentration ≤1% in aqueous media to minimize solvent effects |

| Polymer Carriers | Maintain supersaturation, inhibit precipitation in amorphous solid dispersions | Kollidon VA64, Soluplus, HPMC, PVP [6] [20] |

| Surfactants | Enhance wetting, improve dissolution, solubilize lipophilic compounds | Kolliphor series (RH40, EL, HS15), Poloxamers (P407, P188), Tweens [6] [20] |

| Lipid Excipients | Lipid-based drug delivery for enhanced solubility and bioavailability | Medium-chain triglycerides, partial glycerides, phospholipids [20] |

| Buffer Systems | pH control for solubility and dissolution profiling | Phosphate, acetate, bicarbonate buffers; biorelevant media (FaSSGF, FaSSIF) |

| Volatile Processing Aids | Temporarily enhance solubility during processing (removed later) | Ammonia (for weak acids), acetic acid (for weak bases) [6] |

| 2,6-Dichloroaniline-3,4,5-D3 | 2,6-Dichloroaniline-3,4,5-D3, CAS:77435-48-4, MF:C6H5Cl2N, MW:165.03 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Hydrocinnamic acid-d9 | Hydrocinnamic acid-d9, CAS:93131-15-8, MF:C9H10O2, MW:159.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Decision Framework: Application to Formulation Development

The relationship between solubility measurements, solid-state properties, and formulation strategy follows a logical decision pathway that integrates these critical parameters:

Diagram: Decision framework for formulation strategy based on solubility properties

This decision framework enables formulation scientists to:

- Prioritize compounds with large differences between kinetic and thermodynamic solubility for amorphous formulation approaches

- Allocate appropriate enabling technologies based on absolute solubility values

- Select formulation platforms that maximize bioavailability while ensuring physical stability

- Streamline development timelines by matching compound properties with optimal formulation strategies

Understanding the distinction between thermodynamic and kinetic solubility is fundamental for effective formulation development. Thermodynamic solubility provides the foundation for robust dosage form design, while kinetic solubility offers valuable insights for early compound selection and supersaturation potential. By implementing the troubleshooting approaches, experimental protocols, and decision frameworks outlined in this guide, formulation scientists can effectively navigate solubility challenges, optimize drug delivery systems, and ultimately enhance the bioavailability of poorly soluble drug candidates. The integration of proper solubility assessment with solid-state characterization and appropriate formulation strategies remains crucial for successful pharmaceutical development in an era where poor solubility increasingly represents the norm rather than the exception.

A Toolkit of Solubility Enhancement Technologies: From Conventional to Nanoscale Approaches

Troubleshooting Common Nanomilling and Nanocrystallization Issues

FAQ 1: My nanosuspension is aggregating or showing particle growth over time. What are the main causes and solutions?

Particle aggregation and growth are primarily physical stability issues. The main causes and solutions are:

- Inadequate Stabilization: This is the most common cause. The stabilizer (polymer or surfactant) is not sufficiently adsorbing onto the drug nanoparticle surface to provide electrostatic or steric repulsion.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your stabilizer system. Screen different types and concentrations of stabilizers. Common polymers include hydroxypropyl methylcellulose (HPMC) and polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP). Common surfactants include sodium lauryl sulfate (SLS) and polysorbates (Tweens) [22] [23]. The optimal stabilizer depends on the drug's surface chemistry [24].

- Ostwald Ripening: This is a phenomenon where smaller particles dissolve and re-deposit onto larger particles, leading to an overall increase in mean particle size over time. This occurs due to the higher solubility of smaller particles [23] [25].

- Solution: Ensure a very narrow particle size distribution. Using a broader distribution of stabilizers or combinations can also help to reduce this effect by creating a barrier to dissolution and re-deposition [23].

- Over-milling: Excessive milling time can lead to the generation of high surface energy and may even induce partial amorphization, which can later recrystallize and cause instability [25].

- Solution: Optimize the milling time. Determine the minimum time required to achieve the target particle size to avoid over-processing [26].

FAQ 2: I am observing metal contamination in my final nanosuspension after bead milling. How can I minimize this?

Metal contamination arises from the wear and tear of the milling media (beads) and chamber walls. To minimize it:

- Optimize Milling Parameters: Studies have shown that using a lower rotation speed (e.g., 2 m/s), smaller bead diameter (e.g., 0.3 mm), and a high bead-filling rate (e.g., 75% v/v) can significantly reduce metal contamination while maintaining milling efficiency [26].

- Use Alternative Bead Materials: Instead of traditional zirconia beads, consider using highly cross-linked polystyrene beads, which are a core component of the NanoCrystal technology and are designed to minimize contamination [23] [26].

- Process Parameter Trade-off: Understand that a trade-off exists between milling efficiency and metal contamination. The most aggressive milling conditions will generate the most contamination [26].

FAQ 3: My nanocrystal formulation has poor dissolution performance despite a small particle size. What could be wrong?

If the particle size is on target but dissolution is poor, consider these factors:

- Poor Wettability: The drug nanoparticles may not be being effectively wetted by the dissolution medium.

- Accurate Particle Size Measurement: Ensure that the particle size analysis is performed correctly and that the sample is fully dispersed during measurement. Aggregates in the measurement sample can give a false reading of a larger size [23].

- Formulation and Downstream Processing: If the nanosuspension was dried (e.g., spray-dried, lyophilized) into a powder for tableting or encapsulation, the drying process may have caused irreversible aggregation. The use of appropriate matrix formers or cryoprotectants (e.g., mannitol, sucrose) is critical to maintain the nanocrystalline state and ensure redispersion upon contact with the dissolution medium [22] [28].

FAQ 4: What are the critical process parameters I need to control in a wet bead milling process?

The critical process parameters for reproducible and scalable bead milling are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Critical Process Parameters for Wet Bead Milling

| Parameter | Impact on Process and Product | Typical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Bead Size | Smaller beads provide more contact points and greater milling efficiency for fine nanoparticles, but can increase contamination risk [23] [26]. | 0.3 - 0.1 mm is common for nanomilling [29] [26]. |

| Bead Loading (Filling Rate) | Affects milling energy and efficiency. A higher filling rate typically increases collision frequency but also power consumption [23]. | Often optimized between 50% - 75% of the milling chamber volume [29] [26]. |

| Stirrer Speed | Directly related to the energy input. Higher speed increases collision energy and rate, accelerating size reduction but also heat and contamination [23]. | Must be optimized for each API; lower speeds (e.g., 2 m/s) can reduce metal wear [26]. |

| Milling Time | Determines the final particle size. An optimal time exists; beyond this, over-milling can occur with no further size reduction and potential stability issues [25]. | Determined empirically for each formulation. |

| Drug Concentration | Can affect the viscosity of the suspension and the probability of particle-bead collisions [23]. | Typically ranges from 1% to 40% (w/w) depending on the API and process [29]. |

| Temperature Control | Frictional heat can raise temperature, potentially melting low-melting-point drugs or degrading the API or stabilizers [29]. | Use of a cooling jacket is essential to maintain constant temperature [29]. |

| p,p'-DDE-d8 | p,p'-DDE-d8, CAS:93952-19-3, MF:C14H8Cl4, MW:326.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| p,p'-DDD-d8 | p,p'-DDD-d8, CAS:93952-20-6, MF:C14H10Cl4, MW:328.1 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Essential Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Preparation of a Drug Nanosuspension via Wet Bead Milling

This protocol provides a general method for producing drug nanocrystals, adaptable for laboratory-scale equipment.

Materials:

- Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API)

- Stabilizer(s) (e.g., PVP K-25, HPMC, SLS)

- Purified Water

- Bead Mill (e.g., Apex-Mill, Netzsch, or Dyno-Mill lab-scale model)

- Milling Media (e.g., Yttria-stabilized Zirconia beads, 0.3 mm diameter)

- Cooling System

Method:

- Preparation of Crude Suspension: Disperse the API (e.g., 10% w/w) in an aqueous solution containing the selected stabilizers (e.g., 3% w/w PVP K-25 and 0.25% w/w SLS). Use a stirrer to homogenize the mixture for 30-60 minutes to ensure complete wetting and a uniform pre-suspension [26].

- Mill Setup: Load the milling chamber with the appropriate type and volume of beads (e.g., 75% v/v bead-filling rate). Connect the cooling system and set the temperature to a constant value (e.g., 15-20°C).

- Milling Process: Pump the crude suspension through the milling chamber in recirculation mode. Set the stirrer speed to the target value (e.g., 2 m/s). Begin the process and record the time.

- Sampling: Periodically collect small samples (e.g., every 30-60 minutes) from the outlet stream. Ensure samples are taken after purging a small volume to clear the line.

- Particle Size Analysis: Dilute the samples appropriately and measure the particle size distribution using laser diffraction or dynamic light scattering. Stop the process when the target particle size (e.g., D90 < 500 nm) is achieved and remains constant over two consecutive samples [26].

- Separation: Separate the final nanosuspension from the milling beads using a mesh screen.

Protocol 2: Acid-Base Precipitation (Bottom-Up) Nanocrystallization

This protocol is a solvent-free, bottom-up alternative for drugs with ionizable groups [28].

Materials:

- Etoricoxib (or another ionizable API)

- Stabilizer (e.g., Poloxamer 407)

- 0.5 M HCl Solution

- NaOH Solution

- High-Shear Homogenizer

- Cryoprotectant (e.g., Mannitol)

Method:

- Acidic Drug Solution: Dissolve the drug (e.g., 100 mg) in a 0.5 M HCl solution under magnetic stirring.

- Alkaline Stabilizer Solution: Dissolve the stabilizer (e.g., 0.5% w/v Poloxamer 407) in a NaOH solution of a defined concentration.

- Precipitation: Slowly add the acidic drug solution to the alkaline stabilizer solution under high-speed homogenization (e.g., 10,000 rpm). The rapid change in pH causes instantaneous precipitation of the drug as nanocrystals.

- Homogenization: Continue homogenization for a set time (e.g., 5-15 minutes) to ensure uniform particle size and stabilize the formed nanocrystals.

- Further Processing (Optional): The nanosuspension can be converted into a solid powder using freeze-drying. Add a cryoprotectant like mannitol (5% w/v) to the nanosuspension before lyophilization to protect the particle structure [28].

Technology Workflow and Stabilization Mechanisms

The following diagram illustrates the key decision pathways and technical relationships in selecting and troubleshooting particle size reduction technologies.

Diagram 1: Nanocrystal Technology Workflow and Stabilization

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key materials and their functions for developing nanocrystal formulations.

Table 2: Key Reagents for Nanocrystal Formulation and Stabilization

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function / Rationale for Use |

|---|---|---|

| Polymers (Steric Stabilizers) | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) [26], Hydroxypropyl Methylcellulose (HPMC) [23] | Adsorb onto the drug particle surface, creating a physical barrier that prevents aggregation by steric hindrance. |

| Surfactants (Electrostatic Stabilizers) | Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) [26], Polysorbates (Tween 80) [23], D-α-Tocopheryl polyethylene glycol 1000 succinate (TPGS) | Reduce interfacial tension, improve wettability, and provide electrostatic repulsion between particles via charged head groups. |

| Stabilizer Combinations | PVP + SLS [26], HPMC + SDS | Provide combined electrosteric stabilization, often leading to superior physical stability compared to single stabilizers. |

| Milling Media | Yttria-Stabilized Zirconia (YSZ) beads [26], Highly Cross-Linked Polystyrene Beads [23] | Grinding media for bead milling. Zirconia offers high density and efficiency, while polystyrene minimizes metal contamination. |

| Cryoprotectants | Mannitol [28], Sucrose, Trehalose | Protect nanoparticles from stress during freeze-drying (lyophilization) by forming a glassy matrix, preventing aggregation and aiding redispersion. |

| Kuwanon S | Kuwanon S | Kuwanon S is a prenylated flavonoid for research. This product is for laboratory research use only and not for human or veterinary use. |

| ACHN-975 TFA | Selective HDAC6 Inhibitor|(2S)-3-amino-N-hydroxy-2-[(4-{4-[(1R,2R)-2-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopropyl]buta-1,3-diyn-1-yl}phenyl)formamido]-3-methylbutanamide, trifluoroacetic acid is a potent and selective HDAC6 inhibitor for proteostasis and neurodegenerative disease research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. | (2S)-3-amino-N-hydroxy-2-[(4-{4-[(1R,2R)-2-(hydroxymethyl)cyclopropyl]buta-1,3-diyn-1-yl}phenyl)formamido]-3-methylbutanamide, trifluoroacetic acid is a potent and selective HDAC6 inhibitor for proteostasis and neurodegenerative disease research. This product is For Research Use Only and is not intended for diagnostic or therapeutic use. |

Troubleshooting Common ASD Manufacturing Issues

FAQ 1: How do I select the right polymer for my ASD formulation?

Selecting an appropriate polymer is critical for achieving a stable, amorphous solid dispersion. The polymer must be miscible with the API, inhibit recrystallization, and enable the desired dissolution profile [30] [31].

Key Considerations and Solutions:

- Miscibility Prediction: Use Hansen Solubility Parameters (HSP) for initial screening. Calculate the total solubility parameter (δT) for both the drug and polymer from its dispersion (δD), polar (δP), and hydrogen bonding (δH) components using δT2 = δD2 + δP2 + δH2 [32]. Smaller differences (Δδ) between the drug and polymer parameters suggest higher miscibility [33] [32].

- Experimental Validation: Perform a film casting test [32]. Dissolve the drug and polymer in a volatile common solvent, pour into a Petri dish, and allow the solvent to evaporate. A transparent, homogeneous film indicates good miscibility and solubilization, while an opaque film suggests phase separation.

- Polymer Performance Ranking: Polymers can be ranked by their solubilizing capacity and compatibility. For instance, one study on Ibuprofen ASDs found the following ranking from most to least compatible: KOL17PF > KOLVA64 > Eudragit EPO > HPMCAS [33].

- Stability Assessment: Be aware that high drug loading can lead to demixing and instability. For some polymers, like HPMCAS, only very low drug loadings (e.g., <5% w/w) might be stable at room temperature, while others can maintain metastable states at higher loadings [33].

FAQ 2: My API is heat-sensitive. Can I still use Hot Melt Extrusion (HME)?

While HME involves thermal and shear stress, it can be applied to heat-sensitive APIs with careful planning and screening. The key is to rapidly determine the maximum viable drug loading and the minimum processing temperature required to form the ASD while avoiding degradation [34].

Troubleshooting Protocol:

- Conduct Feasibility Screening: Employ a material-sparing screening process that mimics the kinetic aspects of the extrusion process. This helps accurately predict both achievable API loading and potential degradation risks before committing to a full HME run [34].

- Lower Processing Temperature: Use polymers with lower glass transition temperatures (Tg) or incorporate plasticizers (e.g., triethyl citrate, propylene glycol) to reduce the melt viscosity and the required processing temperature [35] [32].

- Consider Alternative Technologies: If the API is extremely thermolabile, spray drying is often a more suitable technology. It relies on rapid solvent evaporation at lower temperatures, making it advantageous for compounds with poor thermal stability [36] [27].

FAQ 3: I am experiencing low yield with my lab-scale spray dryer. How can I improve it?

Low yield in small-scale spray drying is a common challenge, often due to poor particle collection or the adhesion of fine powders to the drying chamber [36].

Solutions for Improvement:

- Optimize Collection System: If using a Buchi Nano Spray Dryer B-90, ensure the electrostatic particle collector is functioning correctly. This collector is designed to capture charged fine particles (300 nm to 5 µm) with high efficiency (up to 90%) [36].

- Adjust Process Parameters: Optimize the drying gas flow rate and temperature to ensure droplets are sufficiently dry before they contact the chamber walls. A laminar flow pattern can reduce wall collisions [36].

- Check Atomization and Solution Properties: Use a spray mesh (e.g., 4, 5.5, or 7 µm in the B-90) appropriate for your solution's viscosity and surface tension. Ensure the total solids load in the feed solution does not result in excessive viscosity, which adversely affects atomization [36].

FAQ 4: My ASD is recrystallizing during storage or dissolution. What are the causes and solutions?

Recrystallization negates the solubility benefits of ASDs and can occur in the solid state or during dissolution [31].

Troubleshooting Guide:

| Problem Area | Potential Cause | Investigative Experiments & Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Solid-State Stability | High Drug Loading: Exceeds the miscibility limit of the polymer [33] [31]. | Characterize: Use mDSC and XRPD to monitor physical stability. Solution: Reduce drug loading or select a more compatible polymer [35]. |

| Moisture Ingress: Water acts as a plasticizer, increasing molecular mobility [31]. | Characterize: Perform dynamic vapor sorption (DVS). Solution: Use moisture-protective packaging (e.g., sealed aluminum pouches), add desiccants, or select a hydrophobic polymer [35]. | |

| Dissolution Performance | Poor "Parachute" Effect: Inadequate inhibition of precipitation in solution [27]. | Experiment: Perform non-sink dissolution testing. Solution: Add a stabilizing polymer (e.g., HPMCAS) or surfactant to the formulation to maintain supersaturation [37] [27]. |

| Incongruent Release: Drug and polymer do not release simultaneously, leading to drug-rich zones that crystallize [37]. | Experiment: Test dissolution with varying medium compositions. Solution: Incorporate a surfactant to promote congruent release of the API and polymer [37]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization Tests

Protocol 1: Film Casting for Miscibility Screening [32]

Objective: To quickly assess the miscibility and recrystallization inhibition potential of a drug-polymer pair using minimal material.

Materials:

- API and polymer candidates.

- Volatile solvent (e.g., dichloromethane, methanol, acetone).

- Petri dish.

- Analytical balance.

Methodology:

- Intimately mix the API and polymer at target ratios (e.g., 1:1, 1:2, 2:1) and dissolve in a common volatile solvent.

- Pour the solution into a clean Petri dish.

- Allow the solvent to evaporate at room temperature until a thin film is formed.

- Visually inspect the film. A transparent, homogeneous film indicates good miscibility. An opaque or cloudy film suggests phase separation.

- For recrystallization inhibition testing, re-disperse the film in a small amount of solvent, dry again, and inspect for crystal formation.

Protocol 2: Two-Step Non-Sink Dissolution Testing [37] [35]

Objective: To develop a discriminating dissolution method that evaluates the dissolution and supersaturation maintenance ("spring and parachute" effect) of an ASD formulation.

Materials:

- Dissolution apparatus (USP I, II, or miniaturized).

- Dissolution media (e.g., 0.1N HCl for pH 1.2, phosphate buffer for pH 6.8).

- Surfactant (e.g., SDS) if needed.

- HPLC system for assay.

Methodology:

- Begin dissolution in a low-volume, low-pH medium (e.g., 500 mL of 0.1N HCl) to simulate gastric conditions without sink conditions.

- After a specified time (e.g., 30-60 minutes), add a concentrated buffer and/or surfactant solution to the vessel to rapidly shift the pH to intestinal conditions (e.g., pH 6.8) and increase the volume.

- Continue the test for a further 2-4 hours, sampling at regular intervals.

- Plot the dissolution profile. A successful ASD will show a rapid "spring" in concentration followed by a sustained "parachute" (supersaturation), with significantly higher release (e.g., 70-95%) compared to a crystalline reference [35] [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

The following table details key materials commonly used in the development of ASDs via spray drying and HME.

Table 1: Key Research Reagents and Materials for ASD Development

| Material Category & Examples | Function in ASD Formulation |

|---|---|

| Polymers | |

| PVP VA64 (Kollidon VA64) | A widely used copolymer for HME and spray drying. Acts as a matrix former, enhances dissolution, and inhibits crystallization [33] [35]. |

| HPMCAS (AQOAT) | A cellulose-based polymer often used for pH-dependent release and enhancing supersaturation in the intestinal environment. Available in different grades (e.g., LG, MG, HG) [33] [32]. |

| Soluplus | A graft copolymer specifically designed for ASDs. Acts as a matrix polymer and solubilizer, suitable for both HME and spray drying [32]. |

| Eudragit E PO | A methacrylate copolymer soluble in gastric pH. Used to enhance solubility and bioavailability in the stomach [33] [32]. |

| Surfactants & Additives | |

| Sodium Lauryl Sulfate (SLS) | Surfactant used to improve wettability, enhance dissolution, and promote congruent release of drug and polymer from the ASD [37] [35]. |

| Triethyl Citrate | Plasticizer used in HME to lower the processing temperature and melt viscosity of the polymer, beneficial for heat-sensitive APIs [32]. |

| Tartaric Acid | pH modifier used in ASDs of weakly basic drugs to create an acidic microclimate, maintaining solubility and supersaturation [35]. |

| CMV-423 | CMV-423, CAS:186829-19-6, MF:C14H14ClN3O, MW:275.73 g/mol |

| LysRs-IN-1 | (2-Amino-6-oxo-3,6-dihydro-9H-purin-9-yl)acetic Acid|CAS 281676-77-5 |

Process Visualization and Workflows

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision pathway for selecting and troubleshooting between the two primary ASD manufacturing technologies.

ASD Technology Selection and Troubleshooting Pathway

Troubleshooting Guides

Troubleshooting Common Formulation Issues

Table 1: Troubleshooting Common SLN/LNC Formulation Problems

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low Encapsulation Efficiency | - Drug solubility too high in aqueous phase [38]- Highly ordered, perfect lipid crystal structure [39]- Polymorphic transition of lipid expelling drug [38] | - Optimize lipid-to-drug ratio [40]- Use complex lipid mixtures (NLCs) to create imperfect crystals [39] [38]- Increase surfactant concentration (within safe limits) [38] |

| Particle Aggregation & Low Physical Stability | - Inefficient or insufficient surfactant [41] [42]- High particle surface charge (zeta potential) [40]- Ostwald ripening [42] | - Use surfactant combinations [41] [39]- Optimize PEGylated lipid type and concentration (e.g., 0.5-1.5%) [43] [42]- Ensure sufficient steric stabilizer (e.g., PEG chain length >20 units) [42] |

| Poor Drug Release Profile | - Drug deeply embedded in solid, highly ordered lipid core [41] [38]- Insufficient initial "burst release" [41] | - Formulate NLCs by adding liquid lipids to solid lipid [38]- Create a "drug-enriched shell" matrix during cooling [41] |

| Unacceptable Particle Size & Polydispersity | - Inefficient mixing during nanoprecipitation [43]- Insufficient energy during homogenization [41]- Rapid, uncontrolled lipid crystallization [40] | - Employ microfluidics for controlled, reproducible mixing [43]- Optimize homogenization parameters (time, pressure, cycles) [41] [39]- Control cooling conditions post-homogenization [40] |

Troubleshooting Scale-Up and Manufacturing

Table 2: Troubleshooting SLN/LNC Production and Long-Term Stability

| Problem | Possible Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Drug Expulsion During Storage | - Polymorphic transition of lipid from α to more stable β form [38]- Formation of a highly ordered crystalline structure over time [39] | - Use lipid blends to create amorphous "chaotic" structures (NLCs) [38]- Stabilize the less structured alpha polymorph with specific surfactants [38] |

| Batch-to-Batch Variability | - Manual processing methods with poor control [43]- Uncontrolled mixing conditions and energy input [40] | - Implement automated, closed-system platforms [40]- Adopt microfluidics for superior mixing control and repeatability [43] |

| Poor Stability During Storage | - Chemical degradation of lipids or drug [40]- Physical instability (aggregation, crystal growth) [42] | - Incorporate cryoprotectants before freeze-drying [40]- Use plate freezing for fast, controlled freezing to preserve integrity [40] |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Our hydrophilic drug has very low encapsulation efficiency in SLNs. What can we do? The low capacity of standard SLNs for hydrophilic drugs is a known challenge, primarily due to partitioning effects during production [39]. Consider these advanced strategies:

- Lipid-Drug Conjugate (LDC) Nanoparticles: Create an insoluble drug-lipid conjugate bulk first, either by salt formation (e.g., with a fatty acid) or covalent linking. This conjugate is then processed into nanoparticles via high-pressure homogenization. This can achieve drug loading capacities of up to 33% [39].

- Double Emulsion Method (w/o/w): This technique is designed for hydrophilic compounds. The drug is dissolved in water and emulsified into a melted lipid phase to form a primary water-in-oil (w/o) emulsion. This is then dispersed into a second aqueous surfactant solution to form a double (w/o/w) emulsion, followed by solvent evaporation and particle solidification [41].

Q2: How can we modify lipid nanoparticles for targeted drug delivery? Surface modification enables targeted delivery and enhanced cellular uptake [40].

- Ligand Conjugation: Attach ligands (e.g., antibodies, peptides, sugars) to the nanoparticle surface to facilitate specific interactions with receptors on target cells or tissues [40].

- PEGylation: Using PEGylated lipids not only controls size and improves stability but also prolongs circulation time by minimizing non-specific uptake, for example, by the liver. This can enhance delivery to the desired target site [43].

Q3: What is the fundamental difference between SLNs and Nanostructured Lipid Carriers (NLCs), and when should I choose one over the other? The key difference lies in the composition of the lipid matrix and its resulting structure.

- SLNs (1st Generation): Composed of a solid lipid or blend of solid lipids. The main challenge is their tendency to form a highly ordered crystalline structure upon cooling, which can lead to low drug loading and potential drug expulsion during storage [39] [38].

- NLCs (2nd Generation): Composed of a blend of a solid lipid and a liquid lipid (oil). The oil creates imperfections in the crystal lattice, providing more space for drug accommodation. This leads to higher drug loading, reduces the potential for drug expulsion, and can enable better control of drug release [44] [39] [38].

Choose SLNs for simpler formulations where a more sustained release is acceptable. Choose NLCs to maximize drug loading, improve stability for problematic drugs, and achieve more tailored release profiles [44] [38].

Q4: Our lipid nanoparticle formulation suffers from an uncontrollable initial burst release. How can this be modulated? The burst release is often related to the location of the drug within the particle [41].

- To Minimize Burst Release: Aim for a homogenous matrix or drug-enriched core structure. A homogenous matrix, created by dispersing the drug molecularly throughout the lipid, enables controlled and sustained release. A drug-enriched core, formed when the drug recrystallizes before the lipid upon cooling, is also effective for prolonged release [41].

- To Exploit Burst Release: If a burst release is desired (e.g., for an initial loading dose), formulate a drug-enriched shell matrix. This occurs when the lipid solidifies first during cooling, concentrating the drug in the outer shell [41].

Experimental Protocols for Key Characterization assays

Protocol: Assessing In Vitro Drug Release from Lipid Nanoparticles

Objective: To evaluate the release kinetics of a drug from SLN/NLC formulations over time, simulating physiological conditions [38].

Materials:

- SLN/NLC dispersion

- Release medium (e.g., Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS), pH 7.4)

- Dialysis tubing with appropriate molecular weight cut-off (MWCO)

- Recipient vessel with continuous stirring

- Water bath or incubator shaker maintained at 37°C

- HPLC system or other validated analytical method for drug quantification

Method:

- Dispersion Preparation: Accurately measure a volume of the lipid nanoparticle dispersion containing a known amount of the drug.

- Dialysis Setup: Place the dispersion into a pre-hydrated dialysis bag and seal both ends securely.

- Incubation: Immerse the dialysis bag into a large volume (sink conditions) of pre-warmed release medium (e.g., 37°C) with constant, gentle agitation.

- Sampling: At predetermined time intervals (e.g., 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 8, 24, 48 hours), withdraw a known volume of the release medium from the recipient vessel.

- Replenishment: Immediately replace the withdrawn volume with an equal amount of fresh, pre-warmed release medium to maintain sink conditions.

- Analysis: Quantify the drug concentration in each sample using the HPLC method.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the cumulative percentage of drug released and plot it against time to generate the release profile [38].

Protocol: Determining Encapsulation Efficiency and Drug Loading

Objective: To accurately measure the percentage of the total drug that is successfully incorporated into the lipid nanoparticles and the amount of drug carried per unit mass of nanoparticles [44].

Materials:

- SLN/NLC dispersion

- Ultracentrifuge or ultrafiltration devices (e.g., Amicon filters)

- Appropriate solvent for dissolving free (unencapsulated) drug and/or disrupting nanoparticles

- HPLC or UV-Vis spectrophotometer

Method:

- Separation of Free Drug: Subject a known volume of the lipid nanoparticle dispersion to ultracentrifugation (e.g., at high speed for 1 hour) or ultrafiltration to separate the nanoparticles (pellet or retentate) from the aqueous medium containing the unencapsulated drug.

- Quantification of Free Drug: Dilute the collected supernatant/ultrafiltrate appropriately and analyze it to determine the concentration of the unencapsulated drug, [Free Drug].

- Quantification of Total Drug: Dilute an equal volume of the original, unseparated dispersion with a solvent that completely dissolves the lipid nanoparticles (e.g., ethanol, isopropanol). Analyze this sample to determine the total drug concentration in the dispersion, [Total Drug].

- Calculation:

Visualization of Workflows and Structures

SLN/NLC Formulation Workflow

Lipid Nanoparticle Structural Models

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Materials and Their Functions in Lipid Nanoparticle Formulation

| Category | Item Example | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| Solid Lipids | Tristearin, Tripalmitin, Compritol ATO 5, Precirol ATO 5 | Forms the solid matrix of the nanoparticle. Provides a biodegradable and biocompatible structure for controlled drug release [39] [38]. |

| Liquid Lipids (for NLCs) | Miglyol 812, Capryol 90, ethyl oleate | Creates imperfections in the crystal lattice of the solid lipid. Increases drug loading capacity and prevents drug expulsion [38]. |

| Ionizable Lipids (for LNPs) | DLin-MC3-DMA, SM-102, ALC-0315 | Positively charged at low pH for RNA encapsulation, neutral at physiological pH for reduced toxicity. Enables complexation with nucleic acids and facilitates endosomal escape [43]. |

| Phospholipids | Lipoid S100, Soy Phosphatidyl Choline, DSPC | Acts as a "helper lipid." Primarily contributes to the particle membrane/bilayer, improves stability, and can enhance encapsulation efficiency [43] [42]. |

| Sterols | Cholesterol | Incorporated as a "helper lipid." Increases membrane rigidity and stability, reduces drug leakage, and improves in vivo performance [43]. |

| Surfactants/Stabilizers | Poloxamer 188 (Pluronic F68), Tween 80, PEGylated Lipids (e.g., DMG-PEG2000, Brij S20) | Critical for stabilizing the nano-dispersion during and after production. Prevents aggregation and Oswald ripening. PEGylated lipids control particle size, enhance colloidal stability, and prolong circulation time [41] [39] [42]. |

| EMI48 | EMI48, CAS:34564-13-1, MF:C21H20N2O3, MW:348.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| EMI1 | EMI1, CAS:35773-42-3, MF:C20H18N2O3, MW:334.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: Low Complexation Efficiency and Poor Solubility Enhancement

Q: Despite using Cyclodextrins (CDs), my drug's solubility has not improved significantly. What could be the reason, and how can I address this?

- A: Poor complexation efficiency can stem from an improperly matched CD cavity size, unfavorable thermodynamic conditions, or intrinsic drug properties. To resolve this:

- Select the Right Cyclodextrin: The drug molecule must fit sterically and energetically into the CD cavity.

- α-CD: Suitable for small molecules or linear alkyl chains (cavity diameter ~0.50 nm) [45].

- β-CD: Ideal for naphthalene, aromatics, and heterocycles (cavity diameter ~0.65 nm). Note that native β-CD has the lowest water solubility due to intramolecular hydrogen bonding [45].

- γ-CD: Fits larger molecules like steroids and macrolides (cavity diameter ~0.80 nm) [45].

- Use CD Derivatives: If the fit is correct but solubility is low, switch to chemically modified CDs like Hydroxypropyl-β-CD (HP-β-CD) or Sulfobutylether-β-CD (SBE-β-CD). These derivatives have improved water solubility and reduced toxicity. A 2025 study on Chlortetracycline hydrochloride showed that an HP-β-CD inclusion complex prepared by freeze-drying increased solubility by about 9 times compared to the bulk drug [46].

- Optimize the Preparation Method: The complexation method impacts the final product.

- Freeze-drying (Lyophilization) is highly effective for heat-sensitive drugs and can yield a porous, readily soluble product [46].

- Kneading, Spray Drying, and Co-precipitation are other common techniques. If one method fails, try an alternative.

- Select the Right Cyclodextrin: The drug molecule must fit sterically and energetically into the CD cavity.

FAQ 2: Inclusion Complex Instability and Drug Precipitation

Q: My drug precipitates out of solution after forming the inclusion complex, especially upon storage or dilution. How can I improve stability?

- A: Precipitation indicates that the complex is dissociating under stress. This is a common challenge in high-concentration formulations, such as those for subcutaneous delivery [47].

- Conduct a Stability Study: Identify the stress factor causing precipitation.

- pH Change: The stability of the complex can be pH-dependent. Use an appropriate buffer (e.g., citrate, phosphate) to maintain the optimal pH range [48].

- Temperature: Store the product at recommended temperatures. High temperatures accelerate molecular motion, leading to complex dissociation. Use thermal analysis (DSC) to study the thermal behavior of your complex [48].

- Oxidation: For oxygen-sensitive drugs, add antioxidants like EDTA (a chelator) or package the product under an inert atmosphere like nitrogen [48].

- Consider Additives: Surfactants can be used in conjunction with CDs. The formation of CD-surfactant inclusion complexes can modify the system's critical micellar concentration and help stabilize the formulation against precipitation [45].

- Analytical Monitoring: Use HPLC to track the appearance of degradation products or free drug over time, allowing you to pinpoint the instability cause [48].

- Conduct a Stability Study: Identify the stress factor causing precipitation.

FAQ 3: High Viscosity in High-Concentration Formulations

Q: When I increase the drug concentration for subcutaneous injection, my CD-based formulation becomes too viscous. How can I manage this?

- A: This is a well-documented challenge in transitioning from intravenous (IV) to subcutaneous (SC) administration [47]. A survey of formulation experts identified viscosity-related challenges as a top issue (72%) [47].

- Evaluate the CD Concentration: High concentrations of CDs, especially polymeric ones, can significantly increase viscosity. Determine the minimum effective CD concentration required for solubility and stability.

- Explore Alternative Delivery Formats: Instead of increasing drug and CD concentration to reduce volume, consider using an on-body delivery system (OBDS) or SC infusion pump. These systems can deliver larger volumes at lower concentrations, which experts perceive as less risky and costly than developing a high-concentration formulation [47].

- Reformulate: If high concentration is mandatory, re-optimize the formulation. Different CD derivatives or a combination with viscosity-reducing agents might be necessary.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Phase Solubility Study

Objective: To determine the stoichiometry and stability constant (Kc) of the drug-CD complex.

Materials:

- Drug compound (API)

- Selected Cyclodextrin (e.g., HP-β-CD)

- Buffer solutions (various pH)

- Water bath shaker

- Centrifuge

- HPLC system with UV detector

Method:

- Preparation: Prepare a series of aqueous solutions (e.g., 10 mL) with increasing concentrations of CD (e.g., 0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 10 mM).