Drug Discovery and Development 2025: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Breakthroughs

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the modern drug discovery and development process, tailored for researchers, scientists, and development professionals.

Drug Discovery and Development 2025: From Foundational Principles to AI-Driven Breakthroughs

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the modern drug discovery and development process, tailored for researchers, scientists, and development professionals. It begins by exploring the foundational principles of the multi-stage pipeline, from target identification to post-market surveillance. The content then delves into the methodological applications that are transforming the field, with a sharp focus on the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI), machine learning, and novel therapeutic modalities like PROTACs and radiopharmaceutical conjugates. A dedicated section addresses critical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to mitigate high attrition rates and manage costs. Finally, the article examines advanced validation techniques and comparative frameworks essential for ensuring translational success and regulatory approval, synthesizing the latest 2025 trends to offer a forward-looking perspective on the industry.

Laying the Groundwork: Core Stages and Historical Context of Drug Development

The drug development pipeline represents a complex, high-stakes journey from initial concept to marketed therapeutic, requiring on average over a decade and a $2.6 billion investment per approved drug [1]. This end-to-end process integrates diverse scientific disciplines, regulatory frameworks, and technological innovations to address the fundamental challenge articulated by Sir Archibald Garrod over a century ago: "Every active drug is a poison, when taken in large enough doses; and in some subjects, a dose which is innocuous to the majority of people has toxic effects, whereas others show exceptional tolerance of the same drug" [1]. Despite technological advances, the industry faces Eroom's Law (Moore's Law backward), where drug development costs have paradoxically doubled approximately every nine years, highlighting an urgent need for more integrated, efficient approaches [1].

The contemporary pipeline is experiencing substantial growth, with over 12,000 drugs in various development phases globally in 2024, representing a 19% annual growth rate since 2019 [2]. By 2025, the pipeline includes approximately 12,700 drugs in the pre-clinical phase alone, demonstrating continued expansion of therapeutic research [3]. This growth coincides with a transformative shift toward artificial intelligence (AI)-driven approaches, with estimates suggesting 30% of new drugs will be discovered using AI, potentially reducing discovery timelines and costs by 25-50% in preclinical stages [4]. This technical guide deconstructs the core principles, methodologies, and evolving frameworks of the modern drug development process for research professionals.

Phase 1: Discovery and Preclinical Research

The discovery phase initiates the pipeline through identification and validation of therapeutic targets, employing increasingly sophisticated computational and experimental methods to select promising candidate molecules.

Target Identification and Validation

Target identification has evolved from traditional biochemical approaches to integrated systems biology methods. Modern target discovery leverages multi-omics data (genomics, proteomics, transcriptomics) to identify disease-associated proteins or pathways with high therapeutic potential [1]. AI-powered platforms can explore chemical spaces spanning 10³³ drug-like compounds, predicting molecular properties with unprecedented accuracy and enabling autonomous experimental decision-making [1]. Validation methodologies employ genetic techniques (CRISPR, RNAi), biochemical assays, and computational models to establish the target's role in disease pathology and its "druggability" – the likelihood of effectively modulating its activity with a drug-like molecule.

Lead Compound Identification and Optimization

Once targets are validated, researchers identify and optimize lead compounds through structured experimental protocols:

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): Automated screening of compound libraries against biological targets using microplate-based assays. Typical HTS campaigns test 100,000-1,000,000+ compounds in concentration-response formats to identify "hits" with desired activity [1].

Virtual Screening Computational Protocol: As an alternative to physical HTS, this methodology employs molecular docking simulations:

- Prepare compound library database (ZINC, ChEMBL) in appropriate 3D formats

- Generate target protein structure through X-ray crystallography, cryo-EM, or homology modeling

- Define binding site coordinates using known ligand information or pocket detection algorithms

- Perform molecular docking using software (AutoDock Vina, Glide, GOLD) with scoring functions

- Select top-ranking compounds for experimental validation based on binding affinity and pose analysis

Hit-to-Lead Chemistry: Medicinal chemistry optimization cycles employ structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis to improve potency, selectivity, and early ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity) properties. This includes synthetic chemistry, analytical characterization (NMR, LC-MS), and in vitro pharmacological profiling.

Preclinical Development Protocol

Promising lead compounds advance through rigorous preclinical testing to evaluate safety and biological activity:

- In Vitro Pharmacology Profiling: Dose-response assays (IC50/EC50 determination), selectivity panels (including off-target screening), and mechanistic studies in disease-relevant cell cultures. Biomarker identification often occurs at this stage, with 27% of active Alzheimer's trials in 2025 incorporating biomarkers as primary outcomes [5].

- In Vivo Efficacy Studies: Animal models (typically rodents) employing disease-relevant endpoints. The FDA's Animal Model Qualification Program currently has 5 projects in development to establish standardized models [6].

- Toxicology and Safety Pharmacology: Good Laboratory Practice (GLP)-compliant studies assessing:

- Maximum tolerated dose (MTD) and no-observed-adverse-effect level (NOAEL)

- Organ-specific toxicity (hematology, clinical chemistry, histopathology)

- Cardiovascular, central nervous system, and respiratory safety pharmacology

- Genetic toxicology (Ames test, micronucleus assay)

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Discovery and Preclinical Research

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Primary cells, iPSCs, immortalized lines | Target validation, compound screening, mechanism of action studies |

| Animal Models | Genetically engineered mice, PDX models, disease-specific models (e.g., AD transgenic) | In vivo efficacy assessment, toxicology, biomarker identification |

| Antibodies & Proteomics | Phospho-specific antibodies, ELISA kits, multiplex immunoassays | Target engagement quantification, signaling pathway analysis, biomarker measurement |

| Chemical Libraries | Diversity sets, fragment libraries, targeted chemotypes | Hit identification, SAR exploration, lead optimization |

| AI/Computational Tools | Molecular docking software, ADMET predictors, generative chemistry platforms | Virtual screening, compound design, property prediction, de novo molecule generation |

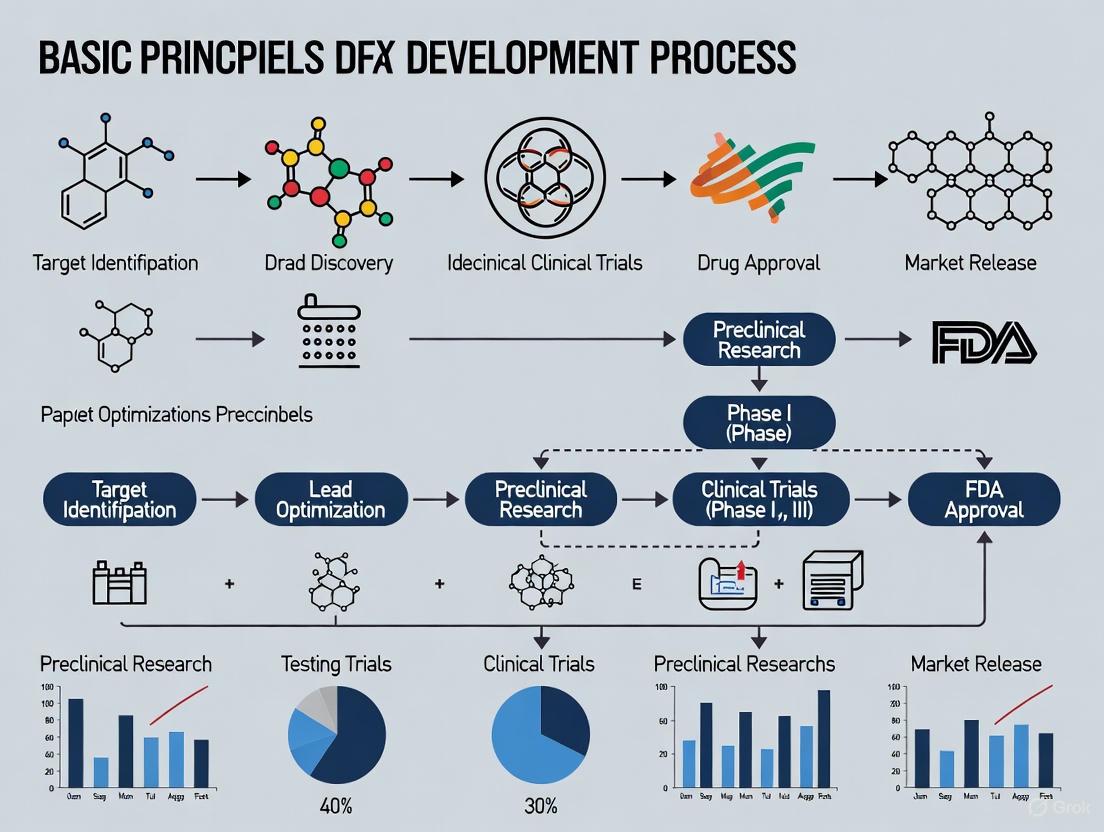

Diagram 1: Discovery and Preclinical Workflow

Phase 2: Clinical Development

Clinical development represents the most resource-intensive phase, evaluating candidate drugs in human subjects through sequentially rigorous trial phases with distinct objectives and methodologies.

Clinical Trial Design and Phases

The clinical development pathway progresses through defined phases with specific objectives, methodologies, and success rates:

Table 2: Global Drug Pipeline by Development Phase (2024-2025)

| Development Phase | Number of Drugs (2024) | Number of Drugs (2025) | Primary Objectives | Typical Duration | Success Rate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phase I | 5,319 | 4,504 | Safety, tolerability, pharmacokinetics | 1-2 years | ~63% [1] |

| Phase II | 4,979 | 4,231 | Therapeutic efficacy, dose-ranging | 2-3 years | ~30% [1] |

| Phase III | 1,671 | 1,197 | Confirmatory efficacy, safety monitoring | 3-4 years | ~58% [1] |

| Pre-registration | 234 | 202 | Regulatory review and approval | 1-2 years | ~90% [7] |

Protocol Development and Implementation

Robust clinical trial protocols incorporate several critical elements:

- Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria: Precise patient population definition using clinical biomarkers and diagnostic criteria. For example, 73% of Alzheimer's trials in 2025 require biomarkers for participant eligibility [5].

- Endpoint Selection: Composite endpoints incorporating clinical outcome assessments (COA), with 67 projects in development within the FDA's Clinical Outcome Assessment Qualification Program [6].

- Randomization and Blinding: Block randomization, stratification by prognostic factors, and double-blind designs to minimize bias.

- Statistical Analysis Plan: Pre-specified analysis methods, sample size justification with power calculations, and interim analysis plans.

Biomarker Implementation and Validation

Biomarkers play increasingly critical roles throughout clinical development:

- Patient Stratification Biomarkers: Enrichment designs targeting specific subpopulations, particularly in oncology where 38% of pipeline drugs target cancer indications [7].

- Pharmacodynamic Biomarkers: Demonstrating target engagement and biological activity, with 8 biomarkers qualified through the FDA's Biomarker Qualification Program [6].

- Predictive Biomarkers: Identifying patients most likely to respond, with the FDA's Biomarker Qualification Program currently developing 59 projects to establish validated biomarkers [6].

Diagram 2: Clinical Development Pathway

Phase 3: Regulatory Review and Approval

The regulatory review phase represents the critical gateway between clinical development and market availability, with evolving frameworks to address therapeutic innovation.

Regulatory Submission Components

A complete regulatory submission integrates evidence from the entire development continuum:

- Chemistry, Manufacturing, and Controls (CMC): Comprehensive documentation of drug substance and product characterization, manufacturing processes, and quality control specifications.

- Nonclinical Pharmacology/Toxicology: Integrated summaries of all in vitro and in vivo studies, with emphasis on predictive toxicology using AI models to forecast potential safety issues [1].

- Clinical Data Integration: Patient-level data from all clinical trials, with clinical outcome assessments playing an increasingly important role in demonstrating patient benefit [6].

- Risk-Benefit Analysis: Quantitative and qualitative assessment of therapeutic value relative to identified risks, often requiring post-market surveillance commitments [8].

Drug Development Tool Qualification

Regulatory agencies have established qualification programs for drug development tools (DDTs) to enhance development efficiency:

Table 3: FDA Drug Development Tool Qualification Programs (as of June 2025)

| Qualification Program | Projects in Development | Letters of Intent Accepted | Qualification Plans Accepted | Total Qualified DDTs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All DDT Qualification Programs | 141 | 121 | 20 | 17 [6] |

| Biomarker Qualification Program | 59 | 49 | 10 | 8 [6] |

| Clinical Outcome Assessment Program | 67 | 58 | 9 | 8 [6] |

| Animal Model Qualification Program | 5 | 5 | 0 | 1 [6] |

| ISTAND Program | 10 | 9 | 1 | 0 [6] |

Therapeutic Area-Specific Considerations

Regulatory pathways continue to evolve for specific therapeutic areas:

- Alzheimer's Disease: The 2025 Alzheimer's disease pipeline includes 182 trials testing 138 drugs, with biological disease-targeted therapies comprising 30% and small molecule DTTs accounting for 43% of the pipeline [5].

- Oncology: Continues to dominate the development pipeline, representing 38% of new medicines in development and 25% of drugs in pre-registration [7].

- Metabolic Disorders: Represent 15% of medicines in pre-registration, with multiple drugs for type 2 diabetes and hyperlipidemia in this late development phase [7].

- Rare Diseases: Orphan medicines comprise a growing share of later pipeline stages, representing 25% of pre-registration drugs in 2025 [7].

Phase 4: Post-Marketing Surveillance and Monitoring

Post-marketing surveillance (PMS) represents the crucial final phase of the drug development lifecycle, providing ongoing safety monitoring in real-world populations far larger and more diverse than clinical trial cohorts.

Post-Marketing Surveillance Frameworks

Modern PMS has evolved from passive reporting systems to active surveillance frameworks:

- Spontaneous Reporting Systems: The FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) collects voluntary reports from healthcare professionals, patients, and manufacturers, serving as an early warning system for potential safety concerns [8].

- Active Surveillance Initiatives: The FDA's Sentinel Initiative leverages real-world data for active surveillance and safety signal detection using distributed data networks [9].

- Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategies (REMS): Required risk management programs for medications with serious safety concerns, incorporating elements to assure safe use [8].

- Aggregated Outcome Data Registries: Emerging frameworks for AI-based medical devices enable performance monitoring through federated health data networks that comply with privacy guidelines [10].

Comprehensive PMS integrates multiple data sources with distinct strengths and limitations:

Table 4: Post-Marketing Surveillance Data Sources and Applications

| Data Source | Key Strengths | Principal Limitations | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spontaneous Reporting | Early signal detection, global coverage, detailed narratives | Underreporting, reporting bias, limited denominator data | Initial signal identification, rare event detection |

| Electronic Health Records | Comprehensive clinical data, large populations, real-world context | Data quality variability, limited standardization, privacy concerns | Signal confirmation, risk quantification, utilization studies |

| Claims Databases | Population coverage, long-term follow-up, economic data | Limited clinical detail, coding accuracy, administrative focus | Utilization patterns, health economics, outcome trends |

| Patient Registries | Longitudinal follow-up, detailed clinical data, specific populations | Limited generalizability, resource intensive, potential selection bias | Long-term safety, disease-specific outcomes, comparative effectiveness |

| Digital Health Technologies | Continuous monitoring, objective measures, patient engagement | Data validation challenges, technology barriers, privacy concerns | Real-world adherence, digital biomarkers, patient-reported outcomes |

Advanced Analytics in Pharmacovigilance

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are transforming pharmacovigilance capabilities:

- Natural Language Processing (NLP): Transforms unstructured narrative text from case reports, clinical notes, and social media into structured, analyzable information, enabling extraction of safety information from previously inaccessible data sources [9].

- Machine Learning for Signal Detection: Advanced algorithms identify potential safety signals from complex datasets by analyzing patterns across multiple data sources simultaneously, detecting subtle associations traditional methods might miss [9].

- Predictive Analytics: Forecasting potential safety issues based on historical patterns and emerging data trends, supporting proactive risk mitigation and resource allocation decisions [9].

- Real-Time Dashboards: Continuous monitoring capabilities and early warning systems for emerging safety concerns, enabling proactive risk management and rapid response to safety signals [9].

Regulatory Intelligence and Compliance

Global regulatory expectations for PMS continue to evolve and expand:

- FDA Requirements: Center on FAERS and REMS programs, with expectations for robust adverse event reporting systems, required post-marketing studies, and effective risk mitigation measures [9].

- EMA and EudraVigilance: Requires comprehensive adverse event reporting to the European pharmacovigilance database and implementation of risk management plans for all marketed products [9].

- ICH Standards: Provides harmonized guidelines for post-marketing surveillance activities, including case report formatting, periodic safety reporting, and signal detection methodologies [9].

- Recent Regulatory Updates: Include strengthened Sentinel Initiative capabilities, enhanced EudraVigilance for advanced signal detection, and ICH guideline updates addressing digital health technologies and AI applications [9].

Diagram 3: Post-Market Surveillance Cycle

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The drug development pipeline is undergoing fundamental transformation through technological innovation, with several disruptive trends reshaping traditional approaches.

Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

AI/ML integration across the development continuum represents the most significant technological shift:

- Target Discovery and Validation: AI processes genomics, proteomics, and patient data to identify novel disease-causing proteins and measurable indicators of drug response, identifying targets overlooked by conventional research [1].

- Generative Chemistry: AI designs entirely new molecules from scratch using sophisticated architectures like Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Transformers, exploring chemical spaces inaccessible to human intuition [1].

- Clinical Trial Optimization: AI algorithms scan electronic health records to identify patients matching complex trial criteria, predict site enrollment rates, and enable digital biomarkers from wearables for continuous patient monitoring [1].

- True End-to-End Systems: Integrated AI platforms ensure tools communicate across all stages, create continuous feedback loops where clinical findings inform molecule design, and enable holistic pipeline optimization considering manufacturability and clinical feasibility from inception [1].

Real-World Evidence and Digital Integration

The expanding role of real-world evidence (RWE) is transforming traditional development paradigms:

- RWE in Regulatory Decision-Making: Regulatory authorities increasingly rely on real-world evidence to support post-marketing safety decisions, including label updates, risk mitigation requirements, and market withdrawal determinations [9].

- Digital Health Technologies: Wearable devices, mobile applications, and remote monitoring systems generate continuous health data streams that support safety monitoring and signal detection, capturing patient experiences beyond clinical settings [9].

- Patient-Centric Approaches: Future PMS systems will increasingly incorporate patient-reported outcomes, digital biomarkers, and personalized safety assessments, engaging patients as active participants in safety monitoring [9].

- Continuous Safety Learning: Evolving frameworks will enable real-time adaptation of safety knowledge and risk management strategies based on emerging evidence throughout the product lifecycle [9].

Therapeutic Innovation Trends

Several therapeutic area developments are reshaping the development landscape:

- Diabetes and Obesity Therapeutics: GLP-1 receptor agonists (semaglutide, tirzepatide) show expanding applications beyond diabetes and obesity to chronic kidney disease, cardiovascular risk reduction, and neurodegenerative conditions [2].

- Alzheimer's Disease Pipeline: The 2025 Alzheimer's pipeline shows diversification beyond amyloid-targeting approaches, with agents addressing 15 basic disease processes including inflammation, synaptic function, and tau pathology [5].

- Women's Health Innovations: New drug classes like neurokinin-3 (NK3) receptor antagonists (fezolinetant) offer non-hormonal alternatives for menopause symptom relief, addressing significant unmet needs [2].

- Rare Disease Focus: Orphan drugs represent growing proportions of late-stage pipelines, with 25% of pre-registration drugs in 2025 having orphan designations, reflecting focus on underserved patient populations [7].

The modern drug development pipeline represents an increasingly sophisticated, technology-enabled continuum from discovery through post-market monitoring. While the fundamental framework remains sequential progression through discovery, preclinical, clinical, regulatory, and post-market phases, each stage is being transformed by AI integration, biomarker advancement, and real-world evidence generation. The persistent challenges of high costs, extended timelines, and late-stage failures are being addressed through more integrated, data-driven approaches that create feedback loops across traditional development silos. For research professionals, success in this evolving landscape requires both deep expertise in specific development domains and systems-level understanding of how innovations in one phase impact subsequent stages. As drug development continues its transformation toward more predictive, patient-centered, and efficient models, the organizations and researchers who master these interconnected processes will lead the next generation of therapeutic innovation.

The journey from a theoretical therapeutic concept to a market-approved medicine is a monumental feat of scientific and clinical endeavor. For researchers and drug development professionals, this path is characterized by a rigorous, multi-stage process designed to ensure safety and efficacy, but which also inherently creates immense challenges in time, financial investment, and resource allocation. The industry standard for bringing a new drug to market is 10 to 15 years, with costs reaching $2.6 billion per approved compound when accounting for failures [11] [12]. This whitepaper deconstructs the core principles of the drug discovery and development process, providing a detailed technical analysis of the chronology, costs, and methodologies that define this lengthy and expensive undertaking. The following workflow diagram (Figure 1) maps the entire process, from initial discovery to post-market surveillance, illustrating the progressive stages and their associated outputs.

Quantitative Analysis of Timelines and Costs

The protracted timeline and immense cost of drug development are driven by the sequential nature of the process and the high probability of failure at each stage. The following tables provide a consolidated quantitative overview of these factors, synthesizing data from recent industry analyses and economic evaluations.

Table 1: Drug Development Stage Timeline and Attrition Analysis [13] [11] [14]

| Development Stage | Average Duration (Years) | Probability of Transition to Next Stage | Primary Reason for Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery & Preclinical | 3 - 6 | ~0.01% (to final approval) | Toxicity, lack of effectiveness in models |

| Phase I Clinical | 1 - 2 | 52% - 70% | Unmanageable toxicity/safety in humans |

| Phase II Clinical | 1 - 3 | 29% - 40% | Lack of clinical efficacy |

| Phase III Clinical | 2 - 4 | 58% - 65% | Insufficient efficacy, safety in large population |

| Regulatory Review | 1 - 1.5 | ~91% | Insufficient evidence, safety/efficacy concerns |

Table 2: Comprehensive Cost Analysis of Drug Development [15] [11] [16]

| Cost Category | Amount (USD Millions) | Context and Inclusions |

|---|---|---|

| Mean Out-of-Pocket Cost | $172.7 million | Direct cash outlay for a single approved drug, nonclinical through postmarketing. |

| Mean Expected Cost | $515.8 million | Out-of-pocket cost inclusive of expenditures on failed drugs. |

| Mean Expected Capitalized Cost | $879.3 million - $2.6 billion | Expected cost including cost of capital (time value of money); varies by study and therapeutic area. |

| Clinical Trial Proportion | 60% - 70% | Percentage of total R&D expenditure consumed by clinical trials (Phases I-III). |

Stage 1: Discovery and Preclinical Research

Experimental Aims and Methodologies

The initial phase aims to identify a viable therapeutic target and a compound that can safely and effectively modulate it.

- Target Identification and Validation: Researchers use bioinformatics, genetic screening (e.g., CRISPR), and molecular biology techniques to identify and confirm the role of a specific biological target (e.g., a protein, gene, or pathway) in a disease mechanism [16].

- Lead Compound Identification: High-Throughput Screening (HTS) of thousands to tens of thousands of compounds (5,000–10,000 is common) is conducted against the validated target using automated, miniaturized assays to identify "hits" [13] [16].

- Lead Optimization: Medicinal chemistry and computer-aided drug design (CADD) are used to iteratively improve the chemical structure of "hit" compounds to become "leads" with enhanced potency, selectivity, and drug-like properties (ADME: Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) [16].

- Preclinical Safety & Efficacy: Optimized lead compounds undergo rigorous in vitro (cell-based) and in vivo (animal model) testing. This includes repeated-dose toxicity studies in at least two animal species, genotoxicity assessment, safety pharmacology (cardiac, respiratory, CNS), and pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) profiling, all conducted under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) standards [13] [12].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Discovery and Preclinical Research

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function |

|---|---|

| Cell Lines | In vitro models for initial target validation, HTS, and efficacy/toxicity testing. |

| Animal Models (e.g., Rodents, Zebrafish) | In vivo systems to study complex pharmacology, toxicity, and disease phenotypes in a whole organism. |

| High-Throughput Screening Assay Kits | Reagent systems enabling rapid, automated testing of thousands of compounds for activity against a target. |

| Analytical Standards & Reagents | Pure compounds and biochemicals for assay development, calibration, and validation (e.g., HPLC, MS). |

| GLP-Compliant Toxicology Assays | Standardized test kits for assessing organ toxicity, genotoxicity, and safety pharmacology in regulated studies. |

| AC 253 | AC 253, MF:C122H196N40O39, MW:2847.1 g/mol |

| Bornyl ferulate | Bornyl ferulate, CAS:90411-21-5, MF:C20H26O4, MW:330.4 g/mol |

Stage 2: Clinical Research – The Human Trials

Clinical research is the most time-consuming and costly part of development, designed to establish safety and efficacy in humans. The following diagram (Figure 2) details the sequential phases, key objectives, and the steep attrition rate that characterizes this stage.

Clinical Trial Experimental Protocols

- Phase I Protocol: First-in-human studies focus on safety and tolerability. A typical protocol involves sequential dose escalation cohorts to determine the Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD) and characterize the pharmacokinetic (PK) profile. Primary endpoints are the incidence and severity of adverse events. Studies enroll 20-100 subjects, either healthy volunteers or patients, over several months to a year [13] [11] [14].

- Phase II Protocol: These are the first controlled studies in patients with the target disease, designed to assess efficacy and further evaluate safety. Protocols are typically randomized and may be placebo-controlled or compared to a standard of care. Key endpoints are often clinical or biomarker-based measures of efficacy (e.g., tumor shrinkage, symptom score reduction). Dose-finding (IIa) and efficacy confirmation (IIb) studies involve 100-300 patients and last 1-3 years [13] [11].

- Phase III Protocol: These are large, randomized, controlled, multi-center "pivotal" trials intended to provide definitive evidence of efficacy and safety for regulatory approval. Protocols are complex, often involving long-term follow-up, multiple sub-studies, and diverse patient populations. They are powered to detect statistically significant differences in primary efficacy endpoints (e.g., overall survival, progression-free survival) and to characterize rare adverse events. These trials enroll 300 to over 3,000 patients and can take 2-4 years to complete [13] [14] [12].

The Converging Forces of Time and Cost

The timelines and costs detailed in previous sections are not independent; they are synergistic factors that create the "staggering" final figure. The relationship is driven by three core principles:

- The Cost of Failure: The financial model is built on the reality that over 90% of drug candidates that enter clinical trials fail [11] [17]. The profits from the rare successful drug must subsidize the sunk costs of all the failures. A study breaking down development costs found that the mean out-of-pocket cost per approved drug was $172.7 million, but this ballooned to $515.8 million when the cost of failed programs was included [15].

- The Cost of Capital (Time Value of Money): Drug development requires investing hundreds of millions of dollars over a decade or more before any revenue is generated. This "time value of money" or opportunity cost is quantified as the cost of capital. When this factor is incorporated, the $515.8 million expected cost inflates to a capitalized cost of $879.3 million to over $2.6 billion per approved drug [15] [11]. A single day's delay in a late-stage trial, where investment is highest, has a massive impact on the final capitalized cost.

- Clinical Trials as the Primary Cost Driver: The clinical phase accounts for 60-70% of total R&D expenditure [16]. This is due to the enormous logistical scale, lengthy duration, and high per-patient costs associated with running GCP-compliant trials across multiple global sites, including expenses for patient recruitment, site management, and regulatory compliance [11] [16].

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

The industry is actively pursuing strategies to mitigate these timeline and cost challenges. Key trends shaping the future of drug development include:

- Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning: AI is projected to drive 30% of new drug discoveries by 2025 [4]. AI platforms are being used to identify drug candidates, design optimal clinical trials by predicting patient profiles and success factors, and analyze patent landscapes to de-risk R&D strategy, potentially reducing discovery timelines and costs by 25-50% in preclinical stages [4] [11].

- Alternative Preclinical Models: To address the high failure rate in translation, researchers are shifting from traditional models to more predictive systems. These include organ-on-a-chip systems, humanized models, and the use of zebrafish for high-throughput in vivo screening. These models aim to generate more human-relevant functional data earlier, improving go/no-go decisions and reducing dependency on slower, costlier mammalian models [18].

- Adaptive Trial Designs and Operational Efficiencies: To control soaring clinical trial costs, sponsors are adopting adaptive trial designs that allow for modification based on interim data, dropping ineffective arms earlier [17]. There is also a push for decentralized clinical trials (DCTs), which use telemedicine and local providers to improve patient recruitment and retention while reducing costs [16].

- Navigating the Patent Cliff and R&D Productivity Crisis: The industry faces a significant "patent cliff" where $350 billion in revenue is at risk from 2025-2029 due to drugs losing exclusivity [17]. Concurrently, R&D productivity is under strain, with the success rate for Phase I drugs falling to 6.7% in 2024 and the internal rate of return on R&D investment dropping to 4.1%, well below the cost of capital [17]. This pressures companies to adopt more data-driven, efficient R&D strategies to remain viable.

In the modern pharmaceutical research and development landscape, target identification and validation represent the critical foundational steps that initiate the entire drug discovery process. This phase focuses on pinpointing a biological molecule, typically a protein or nucleic acid, whose activity can be modulated by a therapeutic agent to produce a beneficial effect against a specific disease [19]. The strategic importance of this stage cannot be overstated; the selection of a poorly validated target is a primary contributor to the high failure rates in later, more costly clinical phases [19]. Consequently, the application of rigorous, multi-faceted methodologies for target identification and subsequent validation is essential for de-risking pipelines and enhancing the probability of translational success. This guide outlines the core principles, current methodologies, and strategic frameworks for target identification and validation, positioning them within the broader context of the drug discovery and development process.

The overarching goal is to establish a causal link between the target and the disease pathophysiology. This involves demonstrating that the target is biologically relevant, is accessible to a drug molecule, and that modulating its activity will lead to a therapeutic outcome with an acceptable safety margin. The contemporary approach to this challenge is increasingly integrated and system-based, moving beyond the traditional "one drug, one target" hypothesis to a more holistic understanding of poly-pharmacology and network biology [20]. This paradigm acknowledges that drugs often interact with multiple targets, and that efficacy—as well as side effects—can arise from complex interactions within biological networks.

Target Identification Strategies

Target identification is the process of discovering potential biological targets that play a key role in a disease pathway. This initial stage leverages a diverse toolkit of experimental and computational approaches to generate a list of candidate targets for further investigation.

Genomic and Proteomic Approaches

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and functional genomics screens are powerful tools for uncovering novel target associations. GWAS analyses large cohorts of patient genomic data to identify genetic variants, such as Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs), that are statistically associated with a disease. Genes located near or at these susceptibility loci become high-priority candidates for further functional validation. Complementarily, functional genomics utilizes tools like CRISPR-Cas9 screens to systematically knock out or knock down every gene in the genome within a disease-relevant cellular model. Genes whose perturbation significantly alters the disease phenotype—such as inhibiting cancer cell proliferation—are identified as potential therapeutic targets [21].

Proteomic analyses, including mass spectrometry-based methods, are used to profile protein expression, post-translational modifications, and protein-protein interactions in diseased versus healthy tissues. Proteins that are differentially expressed or activated (e.g., phosphorylated) in the disease state can indicate potential targets. Advanced mass spectrometry techniques are also being applied in novel validation assays, such as the Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA), to confirm direct drug-target engagement within a complex cellular environment [22].

Computational and Bioinformatic Approaches

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) have evolved from promising concepts to foundational capabilities in modern R&D [22]. In target identification, AI models can integrate vast and disparate datasets—including genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic, and clinical data—to identify and prioritize novel disease targets. These models can uncover complex, non-obvious patterns that are difficult to discern through traditional methods. For instance, AI can be used to deconvolute phenotypic screening hits to predict the protein target responsible for the observed phenotypic effect [22] [19].

Network pharmacology is a system-based approach that analyzes the complex interactions between drugs and multiple targets within a biological network. Instead of examining targets in isolation, it constructs a drug-target network or a chemical similarity network to understand the broader context of a target's function and its relationship to other proteins in the cell [20]. This approach is particularly valuable for understanding poly-pharmacology and predicting potential on-target and off-target effects early in the discovery process. By considering the network properties of a target, researchers can make more informed decisions about which candidates are likely to have a therapeutic effect with minimal side effects.

Table 1: Comparison of Major Target Identification Methods

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Output | Relative Resource Requirement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic/Genetic | GWAS, CRISPR-Cas9 Screens | Genetically validated candidate genes | High |

| Proteomic | Mass Spectrometry, Protein Arrays | Differentially expressed proteins and complexes | High |

| Computational/Bioinformatic | AI/ML, Network Analysis, In-silico Profiling | Prioritized target lists with poly-pharmacology assessment | Low to Medium |

| Ligand-Based | Chemical Similarity Search, Affinity Purification | Protein targets of bioactive small molecules | Medium |

Ligand-Based Identification

When a biologically active small molecule is known but its target is unknown, ligand-based approaches can be employed for target deconvolution. The chemical similarity principle, which states that structurally similar molecules often have similar biological activities, is a cornerstone of this approach [20]. Techniques such as similarity searching in chemical databases using molecular "fingerprints" can help identify known ligands with annotated targets, suggesting a potential target for the query molecule. More direct experimental methods include affinity chromatography, where the bioactive molecule is immobilized on a resin and used to "pull down" its binding partners from a complex protein mixture like a cell lysate. The bound proteins are then identified through mass spectrometry, revealing the direct physical interactors and potential molecular targets [21] [20].

Target Validation Strategies

Once candidate targets are identified, they must be rigorously validated to confirm their therapeutic relevance. Validation provides evidence that modulation of the target has a direct and desired impact on the disease phenotype.

Genetic Validation

Genetic manipulation is a direct method for establishing a causal relationship between a target and a disease.

- Gene Knockdown (RNAi) and Knockout (CRISPR-Cas9): These techniques reduce or eliminate the expression of the target gene in a disease-relevant cellular or animal model. If the loss of the target protein ameliorates the disease phenotype, it provides strong evidence for the target's validity. For example, knocking out an oncogene and observing inhibited tumor growth supports its role in cancer progression.

- Transgenic Overexpression: Conversely, overexpressing the target protein in a model system and observing whether it induces or exacerbates a disease-like phenotype provides another line of validation. This is particularly relevant for dominant-negative mutations or gain-of-function scenarios.

Pharmacological and Functional Validation

This approach uses pharmacological tools, such as small-molecule inhibitors or biologic agents, to modulate the target's activity.

- Tool Compounds: Using a known, high-quality chemical inhibitor or an antibody to block the target's function in a disease model can demonstrate therapeutic potential. The effects on disease-relevant biomarkers and phenotypic endpoints are measured. A key advancement in this area is the use of CETSA to confirm that the tool compound engages the intended target in a physiologically relevant cellular or tissue context, bridging the gap between biochemical potency and cellular efficacy [22].

- Biological Models: The use of physiologically relevant models is crucial. While simple in vitro cell lines are useful, more complex models like 3D organoids or in vivo models such as zebrafish offer whole-organism insights. Zebrafish, with their genetic similarity to humans and scalability, are especially valuable for high-content screening and early-stage efficacy and toxicity testing during validation [19].

Clinical and Biomarker Validation

Linking a target to human disease is a powerful form of validation. This involves:

- Analysis of Clinical Samples: Examining human tissue biopsies, blood samples, or other biofluids from patients to confirm that the target is dysregulated (e.g., overexpressed, mutated, or activated) in the disease state compared to healthy controls.

- Biomarker Development: Identifying and measuring a pharmacodynamic biomarker that reflects the target's activity. During validation, demonstrating that modulation of the target leads to a predictable change in the biomarker strengthens the biological rationale and can provide an early readout of target engagement for future clinical trials [21].

Table 2: Core Target Validation Techniques

| Validation Method | Experimental Approach | Evidence Generated | Key Advantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Validation | CRISPR-Cas9 Knockout/Knockin, RNAi, Transgenic Models | Causal link between target and disease phenotype | High mechanistic clarity |

| Pharmacological Validation | Tool Compounds (Inhibitors/Antibodies), CETSA for binding confirmation | Functional relevance with pharmacologically relevant modulation | Directly tests drug-like intervention |

| Biomarker & Clinical Correlation | Analysis of patient tissues/samples, Biomarker quantification | Relevance of target to human disease pathophysiology | Strongest translational relevance |

| Animal Disease Models | Rodent, zebrafish models of human disease | Efficacy and phenotypic effect in a whole organism | Provides systemic, in vivo context |

Experimental Workflows and Protocols

This section details specific methodologies for key validation experiments, providing a technical reference for researchers.

Workflow for Genetic Validation Using CRISPR-Cas9

The following diagram illustrates the key steps in a CRISPR-Cas9 knockout workflow for target validation.

Detailed Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knockout

- gRNA Design and Cloning: Design a single-guide RNA (sgRNA) sequence (typically 20 nt) targeting an early exon of the target gene. Clone the sgRNA sequence into a CRISPR plasmid vector that also expresses the Cas9 nuclease and a selectable marker (e.g., puromycin resistance).

- Cell Transfection: Transfect the constructed plasmid into a disease-relevant cell line using an appropriate method (e.g., lipofection, electroporation).

- Selection and Cloning: 48 hours post-transfection, add puromycin to the culture medium to select for successfully transfected cells. Maintain selection for 3-5 days. After selection, dissociate the cells and seed them at a very low density to allow for the growth of single-cell-derived colonies.

- Screening for Knockout: Pick individual colonies and expand them. Extract genomic DNA from each clone and perform a surveyor nuclease assay or T7 Endonuclease I assay to detect indel mutations at the target site. Confirm the knockout in positive clones by Sanger sequencing of the PCR-amplified genomic region and by western blot to check for loss of protein expression.

- Functional Assay: Compare the phenotypic behavior of the knockout clones with that of the control (non-targeting gRNA) cells in disease-relevant functional assays. These may include:

- Cell Proliferation Assay (e.g., MTT or CellTiter-Glo)

- Cell Migration/Invasion Assay (e.g., Transwell assay)

- Apoptosis Assay (e.g., Annexin V staining by flow cytometry)

- Transcriptomic or Proteomic Analysis to observe downstream effects.

Workflow for Pharmacological Validation with CETSA

The following diagram outlines the process of using CETSA to confirm target engagement of a tool compound in cells.

Detailed Protocol: Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA)

- Compound Treatment: Aliquot two sets of intact cells (e.g., in suspension or culture). Treat one set with the tool compound and the other with vehicle control (e.g., DMSO). Incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 1 hour) to allow for compound-target engagement.

- Heating: Divide each aliquot into smaller tubes and heat each at different temperatures (e.g., a gradient from 40°C to 65°C) for a fixed time (e.g., 3 minutes) in a thermal cycler.

- Cell Lysis and Separation: Immediately after heating, lyse the cells using freeze-thaw cycles or a detergent-based lysis buffer. Centrifuge the lysates at high speed (e.g., 20,000 x g) to separate the soluble (non-denatured) protein from the insoluble (aggregated) protein.

- Protein Quantification: Collect the soluble protein fraction from each temperature point. Quantify the amount of the target protein remaining in the soluble fraction using a specific detection method. Western Blotting is common for individual proteins, while high-resolution mass spectrometry can be used for proteome-wide studies of engagement [22].

- Data Analysis: Plot the fraction of soluble target protein remaining against the temperature. A rightward shift in the melting curve (increased thermal stability) for the compound-treated sample compared to the control indicates stabilization of the target protein due to direct ligand binding, thus confirming target engagement.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

The following table details essential materials and reagents used in the featured target validation experiments.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Target Validation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 Plasmid | Delivers the gene-editing machinery (gRNA and Cas9 nuclease) into the cell. | lentiCRISPR v2 vector |

| Cell Culture Media & Reagents | Supports the growth and maintenance of the cellular models used for validation. | DMEM, Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), Trypsin-EDTA |

| Selection Antibiotic | Selects for cells that have successfully incorporated the CRISPR plasmid or other genetic constructs. | Puromycin, Geneticin (G418) |

| Tool Compound / Inhibitor | A high-quality chemical probe used to pharmacologically modulate the target's activity. | A well-characterized, potent, and selective small-molecule inhibitor. |

| CETSA Lysis Buffer | Lyses cells after heat treatment while preserving the stability of non-aggregated proteins. | Buffer containing PBS, protease inhibitors, and 0.4% NP-40 detergent. |

| Antibodies for Detection | Specifically detects the target protein in validation assays such as Western Blot or immunofluorescence. | Validated primary antibody against the target; HRP-conjugated secondary antibody. |

| qPCR Assays | Quantifies changes in gene expression levels of the target or downstream genes. | TaqMan Gene Expression Assays. |

| Zebrafish Model | Provides a whole-organism, in vivo system for high-content efficacy and toxicity testing. | Wild-type or transgenic zebrafish embryos. |

| Astin B | Astin B, CAS:151201-76-2, MF:C25H33Cl2N5O7, MW:586.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Galegine hydrochloride | 1-(3-Methylbut-2-en-1-yl)guanidine hydrochloride | 1-(3-Methylbut-2-en-1-yl)guanidine hydrochloride, also known as Galegine. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

Target identification and validation are the cornerstones of a successful drug discovery campaign. A strategic, multi-pronged approach that integrates genetic, pharmacological, and clinical evidence is paramount for building confidence in a target's therapeutic potential before committing significant resources to lead compound development. The field is being transformed by the adoption of system-based approaches like network pharmacology and the integration of advanced AI/ML models for target prediction and prioritization [22] [20]. Furthermore, the routine deployment of functionally relevant assays, such as CETSA for direct target engagement, is closing the critical gap between biochemical activity and physiological effect [22]. By adhering to these rigorous principles and leveraging the latest technologies, researchers can effectively initiate the drug discovery journey, laying a robust foundation for developing the innovative medicines of tomorrow.

The journey from identifying a potential drug candidate to developing a viable lead compound is a critical, multi-stage process in pharmaceutical research. This pathway, foundational to the basic principles of drug discovery and development, typically follows a structured sequence: Target Validation (TV) → Assay Development → High-Throughput Screening (HTS) → Hit to Lead (H2L) → Lead Optimization (LO) → Preclinical Development → Clinical Development [23]. The "hit-to-lead" phase serves as the essential bridge, where small molecule hits discovered from an initial broad screen are evaluated and undergo limited optimization to identify promising lead compounds worthy of further investment [24] [23]. This stage is crucial for de-risking projects early, as only one in about 5,000 compounds that enter preclinical development ever becomes an approved drug [23].

The Hit-to-Lead (H2L) Stage: Objectives and Workflow

Core Objectives of Hit-to-Lead

The primary objective of the hit-to-lead phase is to rapidly assess several hit clusters to identify the two or three hit series with the best potential to develop into drug-like leads [25]. This involves confirming a true structure-activity relationship (SAR) and conducting an early assessment of in-vitro ADMET (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity) properties to select the most promising candidates for full-scale optimization [25]. A typical hit-to-lead project spans six to nine months [25].

The process starts with initial "hits" – compounds identified from a High-Throughput Screen (HTS) that show activity against a biological target. These hits typically display binding affinities in the micromolar range (10â»â¶ M). Through the H2L process, the affinities of the most promising hits are often improved by several orders of magnitude to the nanomolar range (10â»â¹ M) [23].

The Hit-to-Lead Workflow

The transition from hit to lead is a systematic workflow involving hit confirmation, expansion, and early profiling. The following diagram illustrates the key stages and decision points.

Experimental Protocols for Hit Confirmation and Validation

After identifying hits from an HTS, the first critical step is hit confirmation to ensure that the initial activity is reproducible and not an artifact of the screening process [23]. The following table summarizes the quantitative criteria and objectives for this phase.

Table 1: Key Experiments in Hit Confirmation and Characterization

| Experiment Type | Key Measured Parameters | Primary Objective | Typical Assay Formats/Technologies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmatory Testing | Percent inhibition/activation at a single concentration [23] | Confirm reproducibility of primary HTS activity using the same assay conditions [23] | Biochemical assays (e.g., fluorescence polarization, TR-FRET) [24] |

| Dose-Response Curve | ICâ‚…â‚€ (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) or ECâ‚…â‚€ (half-maximal effective concentration) [23] | Determine compound potency over a range of concentrations [23] | Cell-free enzymatic assays; cell-based functional assays [24] [23] |

| Orthogonal Testing | Activity/affinity using a different readout [23] | Validate activity using a different assay technology or one closer to physiological conditions [23] | Binding assays (SPR, ITC), cellular reporter gene assays [24] [23] |

| Secondary Screening | Efficacy in a functional cellular assay [23] | Determine if compound activity translates to a cellular environment [23] | Cell proliferation, cytotoxicity, signal transduction modulation [24] |

| Biophysical Testing | Binding affinity (Kd), kinetics, stoichiometry, conformational change [23] | Confirm direct target binding and rule out promiscuous or non-specific binding [23] | NMR, SPR, ITC, DLS, MST [23] |

Detailed Protocol: Biochemical Potency and Selectivity Assay

This protocol is typical for characterizing hits against an enzyme target, such as a kinase.

- Objective: Determine the potency (ICâ‚…â‚€) and selectivity of confirmed hits.

- Assay Principle: A homogeneous, mix-and-read biochemical assay measuring enzyme activity, often using a detection method like fluorescence polarization (FP) or time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET) to monitor substrate conversion [24].

- Reagents:

- Purified recombinant target enzyme.

- Test compounds (hits) in DMSO.

- Enzyme substrate and any co-factors (e.g., ATP for kinases).

- Detection reagent (e.g., antibody-coupled fluorophore for TR-FRET).

- Assay buffer.

- Procedure: a. Compound Dilution: Prepare a 3-fold serial dilution of the test compound in DMSO, typically starting from 10 µM. Include a control compound and a DMSO-only vehicle control. b. Assay Plate Setup: In a low-volume 384-well plate, transfer 50 nL of each compound dilution (in duplicate) to the assay wells using an acoustic dispenser or pin tool. c. Reaction Mixture Addition: Add the enzyme and substrate in assay buffer to each well. The final reaction volume is 10 µL, and the final DMSO concentration is 0.5%. d. Incubation: Seal the plate and incubate at room temperature for 60 minutes to allow the enzymatic reaction to proceed. e. Detection: Add the detection reagent (e.g., EDTA and detection antibodies for a TR-FRET kinase assay) and incubate for a further 30 minutes. f. Readout: Measure the signal (e.g., TR-FRET ratio) using a compatible plate reader.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate percent inhibition for each well relative to positive (100% inhibition) and negative (0% inhibition) controls.

- Plot percent inhibition versus the logâ‚â‚€ of compound concentration.

- Fit the data to a 4-parameter logistic model to calculate the ICâ‚…â‚€ value.

Detailed Protocol: Cellular Efficacy Assay

- Objective: Evaluate the functional activity and cytotoxicity of hits in a relevant cell line.

- Assay Principle: A cell-based assay measuring a downstream phenotypic effect, such as reporter gene expression, pathway modulation (e.g., phosphorylation via ELISA), or cell viability [24].

- Reagents:

- Cell line expressing the target of interest (native or engineered).

- Test compounds.

- Cell culture media and reagents.

- Assay detection kits (e.g., luciferase for reporter gene, CellTiter-Glo for viability).

- Procedure: a. Cell Seeding: Seed cells into a 96-well cell culture plate at an optimized density and culture for 24 hours. b. Compound Treatment: Treat cells with the test compounds across a concentration range (e.g., 0.1 nM to 10 µM) for a predetermined time (e.g., 6-24 hours). c. Cell Lysis and Detection: Lyse cells and add the assay detection reagent according to the manufacturer's instructions. d. Readout: Measure luminescence or fluorescence on a plate reader.

- Data Analysis:

- Normalize signals to vehicle control (0% effect) and a control inhibitor (100% effect).

- Calculate ECâ‚…â‚€ or ICâ‚…â‚€ values from the dose-response curve.

Hit Expansion and Early Lead Profiling

Following confirmation, several hit clusters are selected for hit expansion. The goal is to explore the structure-activity relationship (SAR) and assess developability by profiling a wider set of analogs against key criteria [23]. An ideal compound cluster at this stage possesses the properties outlined in the table below.

Table 2: Key Profiling Criteria During Hit Expansion

| Property Category | Specific Parameter | Ideal or Target Profile |

|---|---|---|

| Potency & Efficacy | Target Affinity | < 1 µM [23] |

| Cellular Efficacy | Significant activity in a cellular assay [23] | |

| Selectivity & Safety | Selectivity vs. other targets | Demonstrated specificity [23] |

| Cytotoxicity | Low [23] | |

| Interference with CYP450s & P-gp | Low to moderate binding [23] | |

| Drug-Like Properties | Lipophilicity (ClogP) | Moderate [23] |

| Metabolic Stability | Sufficient stability for in vivo testing [23] | |

| Permeability | High cell membrane permeability [23] | |

| Solubility | > 10 µM [23] | |

| Developability | Synthetic Tractability | Feasible synthesis and potential for up-scaling [23] |

| Patentability | Freedom to operate [23] |

Project teams typically select between three and six compound series for further exploration [23]. Analogs for testing are sourced from internal libraries, purchased commercially ("SAR by catalog"), or synthesized de novo by medicinal chemists [23].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential reagents, tools, and technologies used throughout the hit-to-lead process.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Hit-to-Lead

| Tool / Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Primary Function in H2L |

|---|---|---|

| Biochemical Assay Technologies | Transcreener Assays [24], Fluorescence Polarization (FP), TR-FRET, AlphaScreen/AlphaLISA | Measure direct interaction with and modulation of the molecular target in a cell-free system [24]. |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Reporter gene assays, primary cell models, engineered cell lines. | Evaluate compound effects in a physiologically relevant cellular environment, measuring functional efficacy [24] [23]. |

| Biophysical Characterization Instruments | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) [23]. | Confirm binding stoichiometry, affinity (Kd), and kinetics; rule out non-specific aggregation [23]. |

| In-vitro ADME/PK Assays | Metabolic stability (e.g., liver microsomes), Caco-2 permeability, plasma protein binding, cytochrome P450 inhibition [25]. | Early assessment of absorption, distribution, and metabolism properties to predict in vivo pharmacokinetics [25] [23]. |

| Chemical Informatics & AI Tools | In-silico profiling software [25], Machine Learning Potentials (MLPs) like QDÏ€ dataset [26], Generative AI models [27]. | Predict molecular properties, guide synthetic strategy, design novel compounds, and analyze SAR [25] [26] [27]. |

| Compound Libraries | Internal HTS libraries, commercially available compound sets. | Source of analogs for "SAR by catalog" to rapidly explore structure-activity relationships during hit expansion [23]. |

| GW274150 phosphate | GW274150 phosphate, MF:C8H20N3O6PS, MW:317.30 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Lalistat 1 | Lalistat 1, MF:C12H18N4O3S, MW:298.36 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The Screening Cascade: An Integrated View

A successful hit-to-lead campaign relies on an efficient screening cascade that integrates various assay types to triage and prioritize compounds. The following diagram visualizes this multi-tiered filtering process.

The hit-to-lead phase is a cornerstone of modern drug discovery, serving as a critical filter and foundation for all subsequent development stages [24]. By employing a rigorous, multi-parametric approach that balances potency, selectivity, and developability, researchers can de-risk programs and select the most promising lead series for the resource-intensive lead optimization stage. The integration of advanced technologies, including high-throughput chemistry, predictive in-silico tools, and sophisticated biochemical and cellular profiling, continues to enhance the efficiency and success of this pivotal transition from candidate to viable compound [24] [25] [27].

Preclinical research serves as the critical foundation of the entire drug discovery and development pipeline, providing the initial assessment of a compound's safety and biological activity before human testing can commence. This stage employs a combination of in vitro (in glass) and in vivo (within the living) studies to evaluate promising drug candidates, ensuring that only the safest and most effective compounds advance to clinical trials [28]. The primary objectives of preclinical research include identifying a lead drug candidate, establishing its pharmacological profile, determining initial safety parameters, and developing a suitable formulation for administration [28]. These studies must comply with strict regulatory guidelines dictated by Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) to ensure reliable and reproducible results that regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA will accept [28].

The strategic importance of preclinical development continues to evolve with the integration of Model-informed Drug Development (MIDD) approaches. MIDD provides a quantitative framework that uses modeling and simulation to support various drug development decisions, including predicting human pharmacokinetics, optimizing study designs, and interpreting complex exposure-response relationships [29]. By implementing a "fit-for-purpose" strategy that aligns modeling tools with specific development questions, researchers can significantly enhance the efficiency and success rate of the preclinical to clinical transition [29].

Phases of Preclinical Research

Preclinical research is a multi-stage process that systematically transitions from basic scientific discovery to comprehensive safety assessment. The following table outlines the four primary phases of preclinical research, their key activities, and primary outputs [28]:

| Phase | Primary Focus | Key Activities | Output/Deliverable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: Basic Research | Understanding disease biology and identifying intervention points. | - Disease mechanism studies- Identification of drug targets (e.g., proteins, genes)- Target validation via genetic studies and biochemical assays. | A validated biological target implicated in a disease process. |

| Phase 2: Drug Discovery & Candidate Nomination | Finding/designing molecules that effectively interact with the validated target. | - High-throughput screening of compound libraries- Testing in cellular disease models (in vitro)- Initial assessment of potency and selectivity. | A "hit" compound with desired biological activity against the target. |

| Phase 3: Lead Optimization | Refining the chemical structure of "hit" compounds to improve drug-like properties. | - Chemical modification of leads- In vivo testing in animal models- Gathering data on safe/effective dosing.- Preliminary ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) and toxicity studies. | An optimized "lead" drug candidate with supporting efficacy and preliminary safety data. |

| Phase 4: IND-Enabling Studies | Conducting advanced safety and manufacturing studies required for regulatory approval to test in humans. | - Formal GLP safety and toxicology studies- Genetic toxicology assessment- Safety pharmacology- GMP manufacture of drug substance and product. | An Investigational New Drug (IND) application submitted to regulators. |

The entire preclinical process can take several months to a few years to complete, depending on the complexity of the drug candidate and the specific requirements of regulatory authorities [28]. The culmination of this rigorous process is the submission of an Investigational New Drug (IND) application to regulatory bodies such as the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). The IND application includes all data generated from the preclinical studies, along with details on drug manufacturing and proposed plans for clinical trials in humans [28].

Methodological Approaches: In Vitro vs. In Vivo

Preclinical research relies on two complementary methodological paradigms: in vitro and in vivo studies. Each approach offers distinct advantages and addresses different research questions throughout the drug development pipeline. The following table provides a detailed comparison of these core methodologies [30]:

| Aspect | In Vitro | In Vivo |

|---|---|---|

| Definition | Experiments performed in a controlled laboratory environment outside of a living organism (e.g., in glass test tubes or petri dishes). | Experiments conducted inside a living body, such as in animal models (e.g., rodents) or humans. |

| Environment | Controlled and simplified, allowing for the isolation of specific biological components. | Complex and natural, involving the entire living system with all its inherent biological interactions. |

| Primary Advantages | - Faster and more cost-effective- High precision; allows manipulation of single variables- Enables detailed study of cells and mechanisms- Avoids ethical concerns of animal testing. | - Shows real-life interactions within a whole organism- Reveals systemic effects (e.g., on different organs)- Provides data on complex processes like ADME. |

| Key Limitations | - Cannot replicate the full complexity of a living system- Results may not fully predict effects in a whole organism. | - More expensive and time-consuming- Raises ethical considerations for animal use- Can be riskier due to the use of live subjects. |

| Common Applications | - Initial drug screening on cell lines- Mechanism of Action (MoA) studies- Cellular toxicity and efficacy assays.- In vitro fertilization (IVF). | - Animal studies (e.g., in rats) to understand drug effects in a living system- Clinical trials in humans- Testing complex drug effects and toxicity profiles. |

| Data Output Examples | - IC50/EC50 values (potency)- Cell viability and proliferation rates- Target engagement and binding affinity. | - Maximum Tolerated Dose (MTD)- Pharmacokinetic parameters (e.g., half-life, bioavailability)- Overall survival or disease progression in a model organism. |

Experimental Protocols and Key Assays

Essential In Vitro Assays

- Target Identification and Validation: This initial protocol involves using genetic studies (e.g., CRISPR, RNAi), biochemical assays, and animal models to gather evidence confirming that modulating a specific biological target (e.g., a protein or gene) produces a desired therapeutic effect [28].

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS): An automated process where libraries of thousands to millions of compounds are tested for activity against a validated target in cellular or biochemical assays. "Hits" are compounds that show the desired biological activity [28].

- Cell-Based Efficacy and Toxicity Assays: These protocols determine a compound's biological effect (pharmacodynamics) and potential for harm. Examples include:

- MTT/XTT Assay: Measures cell metabolic activity as a proxy for viability and proliferation.

- Flow Cytometry Apoptosis Assay: Quantifies programmed cell death using Annexin V/propidium iodide staining.

- High-Content Imaging: Uses automated microscopy to analyze complex phenotypic changes in cells.

Essential In Vivo Studies

- Pharmacokinetic (PK) Studies: These studies describe how the body affects a drug over time, focusing on ADME. A single dose of the drug is administered to animal models (e.g., rodents), and blood samples are collected at multiple time points. Analysis of drug concentration in plasma determines key PK parameters like half-life (t½), maximum concentration (Cmax), and area under the curve (AUC) [28].

- Safety and Toxicology Studies: These IND-enabling studies are conducted under GLP guidelines to identify potential adverse effects. They involve:

- Repeat-Dose Toxicity Studies: Administering the drug daily for a set duration (e.g., 14 days, 28 days) to determine target organ toxicity and establish a No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL).

- Safety Pharmacology Core Battery: Assessing effects on vital organ systems, including cardiovascular (e.g., telemetry in dogs), central nervous (e.g., Irwin test), and respiratory systems.

- Genetic Toxicology Studies: Evaluating the drug's potential to cause DNA damage (e.g., Ames test, in vitro micronucleus test).

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Successful preclinical research relies on a suite of specialized reagents and tools. The table below details essential materials and their critical functions in the preclinical workflow [28]:

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function in Preclinical Research |

|---|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assays | Immortalized cell lines, Primary cells, Co-culture systems, 3D organoids. | Provide a controlled in vitro system for initial compound screening, mechanistic studies, and preliminary toxicity assessment. |

| Animal Models | Rodents (mice, rats), Non-human primates, Canines, Genetically engineered models (GEM). | Serve as in vivo systems to study complex pharmacology, efficacy in a whole organism, and systemic toxicity before human trials. |

| Bioanalytical Methodologies | Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS), Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA). | Used for quantifying drug concentrations (PK studies) and biomarkers in biological samples (e.g., plasma, tissue). |

| Imaging & Visualization | High-Content Screening (HCS) systems, Confocal microscopy, In vivo imaging (e.g., IVIS). | Enables visualization and quantification of cellular responses, target engagement, and disease progression in live animals. |

| Computational Models | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR), PBPK (Physiologically Based PK) modeling. | In silico tools used to predict compound properties, optimize chemical structures, and simulate human pharmacokinetics. |

| HECT E3-IN-1 | HECT E3-IN-1, MF:C21H26N2O4, MW:370.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| GS-493 | GS-493, CAS:1369426-02-7, MF:C21H14N6O8S, MW:510.44 | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Workflows and Visual Guide

The transition from a biological target to an IND candidate is a logical, sequential process that integrates both in vitro and in vivo data. The following workflow diagrams illustrate this critical path.

Preclinical Drug Development Workflow

In Vitro and In Vivo Interaction

Preclinical research, with its strategic integration of in vitro and in vivo methodologies, remains the indispensable gateway to clinical trials and the development of new therapeutics. The rigorous, phase-appropriate application of these studies—from basic target validation to comprehensive IND-enabling packages—ensures that drug candidates entering human testing have a scientifically sound basis for both expected efficacy and manageable risk [28] [30]. The continued evolution of this field, particularly through the adoption of MIDD approaches and sophisticated in silico tools, promises to enhance the predictive power of preclinical models, further de-risking drug development and accelerating the delivery of innovative treatments to patients in need [29].

Methodological Revolution: How AI and Novel Technologies are Reshaping R&D

The traditional drug discovery paradigm faces formidable challenges characterized by lengthy development cycles, prohibitive costs, and high preclinical trial failure rates. The process from lead compound identification to regulatory approval typically spans over 12 years with cumulative expenditures exceeding $2.5 billion, while clinical trial success probabilities decline precipitously from Phase I (52%) to Phase II (28.9%), culminating in an overall success rate of merely 8.1% [31]. Artificial intelligence (AI) has been extensively incorporated into various phases of drug discovery and development to address these persistent inefficiencies. AI enables researchers to effectively extract molecular structural features, perform in-depth analysis of drug-target interactions, and systematically model the relationships among drugs, targets, and diseases [31]. These approaches improve prediction accuracy, accelerate discovery timelines, reduce costs from trial and-error methods, and enhance success probabilities, establishing AI as a foundational platform in modern pharmaceutical research and development.

AI-Driven Target Prediction and Identification

Selecting the correct biological target is arguably the most critical decision in drug discovery, as an incorrect target early on often leads to failure in late-stage trials [32]. AI enhances target discovery by integrating diverse data sources to uncover hidden patterns and novel therapeutic hypotheses that would be missed by traditional approaches.

Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Data Integration and Multi-Omics Analysis: AI-driven target identification platforms mine genomic, proteomic, transcriptomic, and literature data to identify novel druggable targets [32]. For example, Insilico Medicine's PandaOmics platform combines patient multi-omics data (genomic and transcriptomic), network analysis, and natural-language mining of scientific literature to rank potential drug targets [32]. The experimental protocol involves:

- Data Collection: Aggregate multi-omics data from public repositories (e.g., TCGA, GEO), proprietary datasets, and real-world evidence.

- Natural Language Processing: Implement bidirectional encoder representations from transformers (BERT) models to mine scientific literature, clinical trial records, and patent databases for target-disease associations.

- Network Analysis: Construct protein-protein interaction networks and disease association networks using graph neural networks (GNNs) to identify central nodes representing potential targets.

- Target Prioritization: Apply ensemble machine learning models to generate composite scores based on novelty, druggability, safety, and biological evidence to rank potential targets [32].

Phenotypic Screening Integration: Companies like Recursion Pharmaceuticals fuse high-content cell imaging with single-cell genomics, generating and analyzing cellular and genetic data at massive scale to build maps of human biology that reveal new druggable pathways [32]. Their "Operating System" uses massive image-and-omics datasets to continuously train machine learning models, creating an iterative loop of experiment and design [32].

Case Study: TNIK Discovery for Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis

A representative example of AI-driven target identification is the discovery of TNIK as a novel target for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). Insilico Medicine's AI platform identified TNIK—a kinase not previously studied in IPF—as the top prediction through its multi-omics and literature mining pipeline [32]. This novel target is now being explored further, demonstrating how AI can spotlight therapeutic hypotheses that would have been missed by traditional approaches [32].

Figure 1: AI-driven target identification integrates diverse data sources to prioritize novel therapeutic targets.

AI-Enhanced Virtual Screening

Virtual screening represents one of the most established applications of AI in drug discovery, enabling researchers to efficiently explore ultra-large chemical libraries that would be infeasible to screen experimentally [32].

Technical Approaches and Implementation

Deep Learning for Molecular Property Prediction: Modern AI-based virtual screening employs deep learning architectures to forecast molecular properties including target binding affinity, selectivity, and preliminary ADMET (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity) characteristics [31]. Key methodological approaches include:

- Molecular Representation: Convert chemical structures into machine-readable formats using extended-connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs), SMILES-based representations, or graph-based representations where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges.

- Model Architecture: Implement convolutional neural networks (CNNs) for spatial feature extraction, graph neural networks (GNNs) for molecular graph analysis, or transformer-based architectures for sequence-based molecular representations.

- Training Protocol: Utilize transfer learning from large-scale molecular databases (e.g., ChEMBL, ZINC) followed by fine-tuning on target-specific data. Apply multi-task learning to simultaneously predict multiple properties including binding affinity, solubility, and toxicity.

- Screening Execution: Deploy trained models to score and rank compounds from ultra-large virtual libraries (containing 10^8-10^12 compounds), prioritizing the top candidates for experimental validation [32].

Generative Molecular Design: Advanced generative algorithms including transformers, generative adversarial networks (GANs), and reinforcement learning can propose entirely new chemical structures optimized against a desired target [31]. For example, Insilico Medicine's Chemistry42 engine employs 500 machine learning models to generate and score millions of compounds [32].

Performance Metrics and Comparative Analysis

AI-driven virtual screening has demonstrated significant improvements over traditional methods. Deep-learning virtual screening and machine learning-enhanced scoring often outperform classical QSAR and molecular docking approaches [32]. Neural network models can incorporate predicted 3D structures (e.g., AlphaFold predictions) to refine binding site analysis, further enhancing prediction accuracy [32].

Table 1: AI-Enhanced Virtual Screening Approaches and Applications