Drug-Receptor Interactions and Signal Transduction: From Molecular Foundations to Therapeutic Innovation

This comprehensive review explores the intricate landscape of drug-receptor interactions and their role in cellular signal transduction, a cornerstone of modern pharmacology and drug development.

Drug-Receptor Interactions and Signal Transduction: From Molecular Foundations to Therapeutic Innovation

Abstract

This comprehensive review explores the intricate landscape of drug-receptor interactions and their role in cellular signal transduction, a cornerstone of modern pharmacology and drug development. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, the article synthesizes foundational principles with cutting-edge methodological advances. It delves into the molecular mechanisms of major receptor families, the application of innovative technologies like Cryo-EM and AI in target discovery, and strategies to overcome challenges in drug efficacy and selectivity. Furthermore, it examines computational and experimental frameworks for validating drug effects on signaling networks and compares therapeutic targeting strategies. By integrating these perspectives, the article aims to bridge fundamental research with clinical translation, offering a roadmap for developing more precise and effective therapeutics.

The Molecular Language of Cellular Signaling: Decoding Receptor Families and Interaction Principles

Within the framework of drug receptor interactions and signal transduction pathways research, a fundamental principle is that drugs primarily exert their effects by modulating the activity of specific macromolecular targets in the body [1]. These interactions initiate a cascade of biochemical events, or signal transduction, that ultimately results in an observed physiological or therapeutic effect [1]. The most critical classes of these drug targets include receptors, ion channels, enzymes, and transporters [2]. Understanding the function and signaling mechanisms of these targets is not merely an academic exercise; it forms the essential foundation for rational drug design, enabling the development of novel, targeted therapies that improve patient outcomes and advance the entire field of pharmacology [1]. This review provides an in-depth exploration of these major drug target classes, detailing their structures, signaling mechanisms, and the experimental methodologies used to investigate them.

Major Drug Target Classes: Structure, Function, and Signaling

Drug targets are intrinsic biological macromolecules to which a drug binds to produce its pharmacological effect [1]. The interaction between a drug and its target is highly specific, aiming to achieve the intended medical benefit while minimizing side effects, though no drug possesses complete specificity [1]. The principal classes of drug targets are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Core Classes of Drug Targets and Their Characteristics

| Target Class | Key Function | Signaling Mechanism | Example Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Receptors [2] | Recognize specific ligands and initiate intracellular signaling cascades. | Varies by subtype (e.g., GPCRs activate G proteins, Nuclear receptors regulate gene transcription) [3] [4]. | Agonists (mimic endogenous ligands); Antagonists (block endogenous ligands) [2]. |

| Ion Channels [2] | Facilitate the movement of ions across cell membranes. | Ligand-gated: Open upon agonist binding [2]. Voltage-gated: Open in response to membrane potential changes [2]. | Channel blockers (e.g., Dihydropyridines for Ca2+ channels), allosteric modulators (e.g., Benzodiazepines for GABAA receptor) [2]. |

| Enzymes [2] | Catalyze biochemical reactions within a cell. | Drugs often act as inhibitors, binding to the enzyme and preventing substrate conversion, thereby disrupting metabolic pathways [2]. | Substrate analogs (e.g., Fluorouracil), irreversible inhibitors. |

| Transporters [2] | Move ions or metabolites across cell membranes. | Drugs typically block the transporter, preventing the reuptake or movement of substances (e.g., neurotransmitters, ions) [2]. | Inhibitors (e.g., Furosemide blocking Na+-K+-2Cl- cotransporter) [2]. |

Receptors

Receptors are proteins, located on cell membranes or intracellularly, that transduce signals from endogenous ligands or drugs to intracellular mediators [1]. They are crucial for chemical communication and homeostasis [1]. Receptors are classified based on their mechanism and location.

G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

GPCRs constitute the largest family of membrane receptors and are characterized by seven transmembrane alpha-helices [4]. Upon ligand binding, the receptor undergoes a conformational change, activating heterotrimeric G proteins (e.g., Gs, Gi, Gq) [4]. The activated G protein subunits then modulate effector proteins like adenylyl cyclase (which produces cAMP) or phospholipase C (which generates IP3 and DAG), leading to diverse cellular responses such as changes in heart rate or neurotransmission [4].

Ion Channel Receptors

Also known as ligand-gated ion channels, these receptors form a pore that opens upon binding of a neurotransmitter, allowing specific ions (e.g., Na+, K+, Ca2+, Cl-) to flow across the membrane [2] [4]. This ion movement rapidly alters the membrane potential, making them critical for fast synaptic transmission [4]. For example, acetylcholine binding to nicotinic receptors causes sodium influx and depolarization [4].

Enzyme-Linked Receptors

These single-pass transmembrane receptors possess intrinsic enzymatic activity or associate directly with enzymes [4]. A prominent subfamily is the Receptor Tyrosine Kinases (RTKs). Ligand binding (e.g., insulin or growth factors) induces receptor dimerization and autophosphorylation, creating docking sites for intracellular signaling proteins and initiating complex cascades that regulate processes like cell growth and glucose uptake [4].

Nuclear Receptors

Nuclear receptors (NRs) are ligand-activated transcription factors located inside the cell [3]. They sense hydrophobic signaling molecules, such as steroid hormones (e.g., estrogen, cortisol), thyroid hormone, and vitamin D [3]. Upon ligand binding, they undergo a conformational change, dimerize, and bind to specific DNA sequences called hormone response elements (HREs) in the promoter or enhancer regions of target genes, thereby directly modulating gene expression [3]. This process plays a crucial role in development, metabolism, and reproduction [3].

Second Messengers in Signal Transduction

The activation of many receptors does not directly produce the cellular effect but instead triggers the production or release of intracellular signaling molecules known as second messengers. These molecules relay and amplify the signal from the first messenger (the ligand) to provoke a broad, coordinated cellular response [4].

Table 2: Key Second Messengers in Cellular Signaling

| Second Messenger | Primary Function | Generating Enzyme/Process | Downstream Effect |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclic AMP (cAMP) [4] | Activates Protein Kinase A (PKA). | Synthesized from ATP by adenylyl cyclase (often stimulated by GPCRs). | Phosphorylation of various target proteins; e.g., increased heart rate and contractility. |

| Inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate (IP3) & Diacylglycerol (DAG) [4] | IP3 releases Ca2+ from intracellular stores; DAG activates Protein Kinase C (PKC). | Generated by phospholipase C (PLC) from membrane lipid PIP2. | Calcium-mediated events (e.g., muscle contraction); PKC-mediated phosphorylation. |

| Calcium Ions (Ca2+) [4] | A versatile intracellular signal. | Released from ER via IP3 receptors or enters through plasma membrane channels. | Triggers exocytosis, muscle contraction, enzyme activation, and apoptosis. |

| Nitric Oxide (NO) [4] | A gaseous, membrane-diffusible messenger. | Synthesized by nitric oxide synthase (NOS). | Activates guanylyl cyclase to produce cGMP, leading to smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilation. |

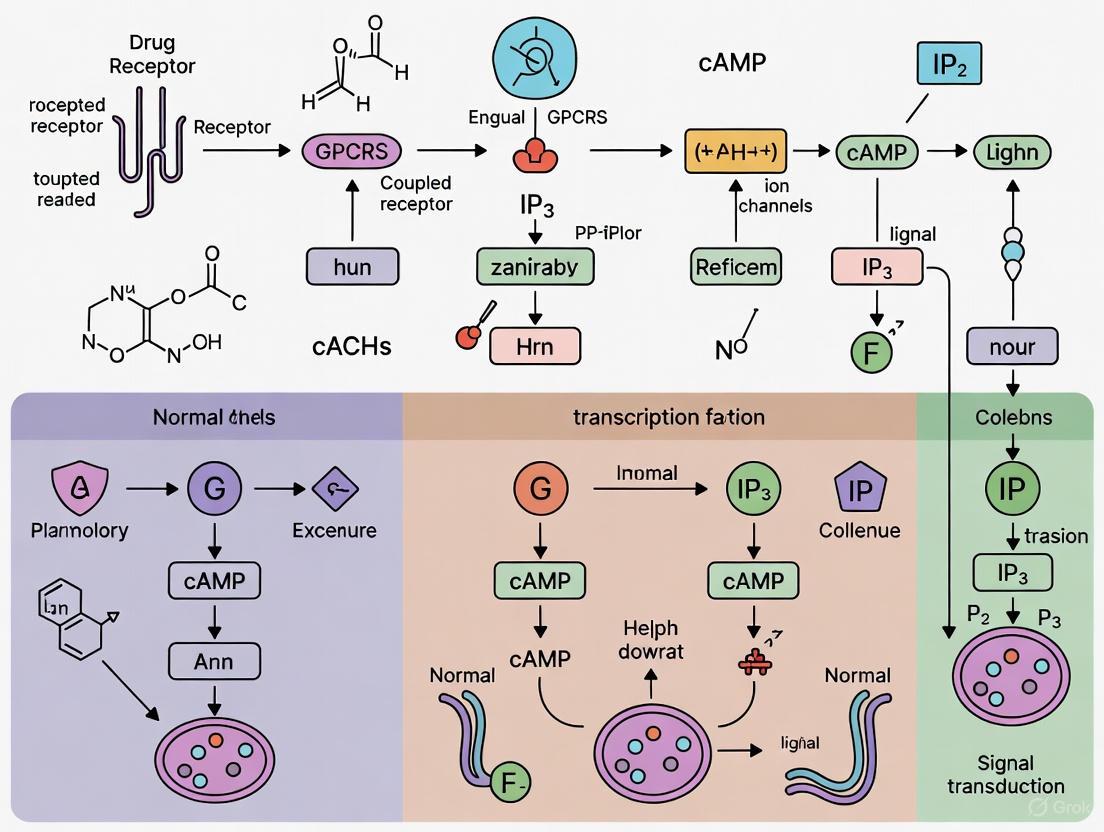

Diagram 1: Key signaling pathways for major receptor classes.

Advanced Research Methodologies in Target Identification and Validation

Modern drug discovery relies on sophisticated technologies to identify and validate the molecular targets of bioactive compounds, particularly for complex natural products or novel synthetic molecules. The workflow below outlines a generalized strategy for this process.

Diagram 2: General workflow for identifying drug targets.

Key Experimental Protocols and Reagents

Several powerful chemical biology-driven methods have been developed for target identification. The following table details essential reagents and their functions in these experimental protocols.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Drug Target Identification

| Research Tool / Method | Core Function | Key Reagents & Techniques |

|---|---|---|

| Affinity Purification (Target Fishing) [5] | Isolates target proteins from complex biological mixtures using a immobilized drug molecule as bait. | Biotin-/Immobilized Probe: A derivative of the drug compound attached to a solid support (e.g., sepharose beads) or biotin for capture. Cell Lysate: Source of potential target proteins. Streptavidin Beads: Used to capture the biotinylated probe-protein complex. |

| Click Chemistry & Photoaffinity Labeling [5] | Covalently "tags" the drug target within live cells for subsequent isolation and identification, providing high spatial and temporal resolution. | Clickable Probe: A drug analog containing a small, bioorthogonal chemical group (e.g., an alkyne). Photoaffinity Group: A chemical moiety (e.g., diazirine) that forms a covalent bond with the target protein upon UV irradiation. Fluorescent Azide/Biotin Azide: For visualization or pull-down after the "click" reaction. |

| Cellular Thermal Shift Assay (CETSA) [5] | Measures drug engagement by detecting changes in the thermal stability of the target protein upon ligand binding. | Heated/Cooled Blocks: For precise temperature control of cell or protein lysates. Protease Inhibitors: To prevent protein degradation during the assay. Antibodies/Western Blot or MS: For detecting and quantifying the remaining soluble target protein. |

| Drug Affinity Responsive Target Stability (DARTS) [5] | Leverages the principle that a drug-bound protein is less susceptible to proteolytic degradation. | Drug and Vehicle Control: For treatment and control samples. Pronase or Other Proteases: For limited proteolysis. SDS-PAGE & Western Blot/Mass Spectrometry: To analyze protease-resistant protein fragments. |

| Network-Based Target Discovery [6] | Uses computational analysis of protein-protein interaction networks to predict optimal co-target combinations to overcome drug resistance in diseases like cancer. | Protein-Protein Interaction (PPI) Databases: (e.g., HIPPIE) providing high-confidence interaction data. Shortest Path Algorithms: (e.g., PathLinker) to identify key communication nodes. Genomic Datasets: (e.g., TCGA, AACR GENIE) for mutation co-occurrence analysis. |

A Protocol for Affinity Purification-Based Target Identification

The classic affinity purification strategy, continuously refined with advancements in chemical biology, remains a cornerstone technique for identifying direct protein targets [5]. The detailed methodology is as follows:

- Probe Design and Synthesis: The investigated drug molecule is chemically modified to incorporate a functional handle, such as a primary amino or alkyne group, without destroying its biological activity. This handle is used to covalently link the drug to a solid support matrix, such as sepharose beads, creating the affinity resin [5].

- Sample Preparation and Incubation: A complex protein mixture, typically a cell lysate from a relevant tissue or cell line, is prepared. The lysate is pre-cleared with bare beads to remove non-specifically binding proteins. The pre-cleared lysate is then incubated with the drug-conjugated affinity resin to allow the formation of specific drug-target complexes [5].

- Washing and Elution: After incubation, the resin is extensively washed with buffer to remove unbound and weakly associated proteins. The specifically bound target proteins are then eluted using a high-salt buffer, a detergent, or, most specifically, with an excess of the free, non-modified drug molecule, which competes for binding and releases the target [5].

- Target Identification and Validation: The eluted proteins are separated by SDS-PAGE and identified using analytical techniques, most commonly tryptic digestion followed by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) [5]. The putative target must then be validated through orthogonal methods, such as cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA), knockout/knockdown studies, or functional assays, to confirm the physiological relevance of the interaction [5].

The precise definition of drug target classes—receptors, ion channels, enzymes, and transporters—and a deep understanding of their distinct signaling transduction pathways are fundamental to biomedical research and therapeutic development. The ongoing refinement of target identification technologies, ranging from classical affinity purification to modern chemical proteomics and network-based computational approaches, continues to illuminate the complex pharmacological mechanisms of both old and new drugs. This expanding knowledge base is critical for systematically designing novel, focused combination therapies and personalized medicine strategies that effectively target the underlying molecular mechanisms of disease, ultimately aiming to improve therapeutic efficacy and patient outcomes.

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) represent the largest family of signaling proteins in animals and constitute the largest class of membrane protein targets for therapeutic drugs. [7] [8] The human genome encodes nearly 800 distinct GPCR subtypes, which are integral membrane proteins characterized by a common core of seven transmembrane α-helical domains (7TM). [9] [7] These receptors recognize a vast array of extracellular signals—including photons, ions, lipids, neurotransmitters, hormones, and peptides—and transduce these signals across the cell membrane to initiate intracellular responses. [10] [8] Due to their central role in physiological processes and their pharmaceutical importance—targeted by approximately 34% of FDA-approved drugs—understanding GPCR structure, activation mechanisms, and signaling pathways remains a critical focus in biomedical research and drug discovery. [11] [8]

Structural Architecture of the GPCR Superfamily

Common Topology and Structural Classification

All GPCRs share a conserved seven-transmembrane (7TM) topology, forming a bundle of helices connected by three extracellular loops (ECLs) and three intracellular loops (ICLs). [12] [9] This structure creates an extracellular N-terminus and an intracellular C-terminus, whose lengths and domains vary considerably across the superfamily. [7] GPCRs are structurally and phylogenetically classified into five main families in the GRAFS system: Glutamate, Rhodopsin, Adhesion, Frizzled/Taste2, and Secretin. [13] [14] The Rhodopsin family (Class A) is the largest and most extensively studied, comprising about 90% of all GPCRs. [14] [9]

Table 1: Major GPCR Families and Their Characteristics

| Family | Representative Members | Key Structural Features | Ligand Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rhodopsin (Class A) | β2-adrenergic receptor, Rhodopsin, Dopamine receptors | Short N-terminus; ligand binding within TM domain | Adrenaline, Dopamine, Light [10] [9] |

| Secretin (Class B) | Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor (GLP-1R), Parathyroid hormone receptor | Large N-terminal extracellular domain (ECD) with conserved fold stabilized by disulfide bonds [12] | Peptide hormones (Glucagon, PTH) [12] |

| Glutamate (Class C) | Metabotropic glutamate receptors, Calcium-sensing receptor | Large bi-lobed Venus flytrap ECD; often form dimers [10] | Glutamate, Calcium [10] |

| Adhesion | GPR56, EMR2 | Very long N-terminus with adhesion domains; GPS proteolytic site [14] | Extracellular matrix proteins [14] |

| Frizzled/Taste2 | Frizzled receptors, Smoothened | Cysteine-rich domain in ECD [13] | Wnt proteins, Bitter tastants [13] |

Ligand Recognition and Binding Pockets

GPCRs recognize their diverse ligands via several mechanisms. For small molecules (e.g., adrenaline in aminergic receptors), the primary binding pocket is located within the upper third of the 7TM bundle. [10] [8] In contrast, peptide-binding GPCRs often involve the extracellular loops (ECLs) and the N-terminal tail in ligand engagement. [12] Class B GPCRs exhibit a distinctive mechanism where the peptide ligand's C-terminus interacts with the large N-terminal ECD, while its N-terminus inserts into the 7TM core, effectively acting as a dual-domain agonist. [12]

The conserved seven-transmembrane helix architecture forms the foundation for a specialized set of structural microdomains and motifs crucial for GPCR function. The "DRY" motif at the intracellular end of TM3 is essential for G protein coupling and receptor activation, while the "NPxxY" motif in TM7 contributes to receptor stability and activation. [12] A highly conserved disulfide bridge between cysteine residues in ECL2 and TM3 stabilizes the extracellular region. [12] These receptors function as sophisticated allosteric machines, with their conformational equilibrium and signaling efficacy modulated not only by ligands but also by ions (e.g., sodium), lipids, cholesterol, and water molecules embedded within the TM bundle. [10]

GPCR Activation Mechanisms

The Activation Cycle and Conformational Changes

GPCR activation follows a fundamental mechanism where extracellular ligand binding induces conformational changes that are transmitted approximately 40 angstroms across the cell membrane to the intracellular surface. [8] This process can be conceptualized as a conformational transition from an inactive (R) state to an active (R*) state.

The following diagram illustrates the core conformational changes during GPCR activation and the critical intracellular partners involved in signal propagation and regulation.

Upon agonist binding, the receptor undergoes key conformational rearrangements, notably an outward movement of TM6 on the intracellular side. [12] This movement creates a crevice for coupling with intracellular transducer proteins. Recent research by Guo et al. demonstrates that agonist-induced structural disorder on the cytoplasmic side enables this versatile coupling, revealing the molecular basis for GPCR activation mechanisms. [15] [7] The receptor functions as a guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), catalyzing the exchange of GDP for GTP on the Gα subunit of heterotrimeric G proteins. [9] [8]

Regulation and Desensitization

To prevent sustained signaling, activated GPCRs undergo a tightly coordinated regulation process. This begins with phosphorylation of the receptor's intracellular loops and C-terminal tail by G protein-coupled receptor kinases (GRKs). [13] [8] This phosphorylation creates a "barcode" that promotes the binding of β-arrestins. [13] β-arrestin binding sterically hinders further G protein coupling (desensitization) and facilitates receptor internalization via clathrin-coated pits. [9] [8] The internalized receptor can then be dephosphorylated and recycled to the membrane (resensitization) or targeted for degradation (downregulation). [9]

Signal Transduction Pathways

Primary G Protein-Mediated Signaling

GPCRs primarily signal through heterotrimeric G proteins, which consist of Gα, Gβ, and Gγ subunits. [13] [9] The human genome encodes four main Gα families (Gs, Gi/o, Gq/11, and G12/13), each initiating distinct downstream signaling cascades. [13] [8] The specificity of G protein coupling underlies the diverse functional outcomes of GPCR activation.

Table 2: Major G Protein Signaling Pathways

| G Protein | Primary Effector(s) | Second Messenger & Changes | Representative Physiological Roles |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gs (Stimulatory) | Stimulates Adenylyl Cyclase (AC) | ↑ cAMP, activates PKA [9] [8] | Increased heart rate, gluconeogenesis [9] |

| Gi/o (Inhibitory) | Inhibits Adenylyl Cyclase (AC) | ↓ cAMP, inhibits PKA [9] [8] | Reduced heart rate, neural modulation [9] |

| Gq/11 | Activates Phospholipase C-β (PLCβ) | ↑ IP3 & DAG; ↑ Ca2+; activates PKC [9] [8] | Smooth muscle contraction, hormone secretion [9] |

| G12/13 | Activates RhoGEFs | Activates Rho GTPase [13] [8] | Cell cytoskeleton reorganization, migration [13] |

The following pathway map integrates the major G protein and β-arrestin signaling routes, highlighting the production of key second messengers and downstream cellular responses.

Compartmentalized Signaling and β-Arrestin Pathways

A critical advancement in understanding GPCR signaling is the concept of signal compartmentalization. Rather than being uniformly distributed, second messengers like cAMP are organized into highly localized nanodomains, often regulated by phosphodiesterases (PDEs) that hydrolyze cAMP and limit its diffusion. [16] Furthermore, GPCRs can initiate distinct signaling profiles based on their subcellular localization, with receptors at the plasma membrane, endosomes, Golgi apparatus, and even the nucleus eliciting unique cellular responses. [16]

Beyond G proteins, GPCRs activate β-arrestin-mediated signaling. Once recruited to the activated and GRK-phosphorylated receptor, β-arrestins not only mediate desensitization and internalization but also serve as scaffolds to activate various kinase pathways, such as the ERK/MAPK cascade, leading to diverse cellular outcomes like cell growth and survival. [13] [8]

Experimental Approaches and Research Toolkit

The complex study of GPCRs relies on a multidisciplinary arsenal of structural, biophysical, and pharmacological techniques. The field has been revolutionized by advances in structural biology, particularly cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM), which has enabled the visualization of GPCRs in fully active complexes with G proteins and β-arrestins. [12] [8]

Table 3: Key Experimental Methods in GPCR Research

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Key Applications in GPCR Research |

|---|---|---|

| Structural Biology | X-ray Crystallography, Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM), NMR Spectroscopy [10] [8] | Determining high-resolution structures of GPCRs in different states (inactive, active, transducer-bound); studying dynamics. [10] [12] |

| Biophysics & Spectroscopy | Hydrogen/Deuterium Exchange-Mass Spectrometry (HDX-MS), Double Electron-Electron Resonance (DEER), FRET [10] [8] | Probing conformational changes, dynamics, and distances between specific residues. [10] [8] |

| Cell-Based Assays | BRET/FRET Biosensors, GloSensor cAMP assay, Tango/Precocious-Tango β-arrestin recruitment assay [13] | Measuring second messenger production (cAMP, Ca2+), kinase activation, and pathway-specific signaling (G protein vs. β-arrestin). [13] |

| Pharmacology & Simulation | Molecular Dynamics (MD) Simulations, Virtual Screening [10] [8] | Understanding activation pathways, predicting ligand-receptor interactions, and rational drug design. [10] [8] |

| Hederacolchiside E | Hederacolchiside E, CAS:33783-82-3, MF:C65H106O30, MW:1367.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Eupalinolide K | Eupalinolide K, MF:C20H26O6, MW:362.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The experimental workflow for characterizing GPCR ligands and their functional outcomes involves a multi-step process to delineate complex signaling profiles, as shown in the following diagram.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

- Stabilized Receptor Constructs (e.g., BRIL fusions, thermostabilized mutants): Protein engineering is crucial for enhancing receptor stability and crystallization for structural studies. [10] [8]

- G Protein Mimetics (e.g., NanoBits, mini-G proteins, nanobodies): These tools are used to stabilize the active conformation of GPCRs for structural studies or to measure G protein activation in functional assays. [8]

- Pathway-Selective Biosensors (e.g., GloSensor cAMP, Tango β-arrestin kits): These are cell-based assay systems that allow for the specific and quantitative measurement of individual signaling pathways downstream of GPCR activation. [13]

- Intracellular Biased Allosteric Modulators (BAMs): Small molecules that bind to intracellular allosteric sites and stabilize specific receptor-transducer complexes, enabling the study and promotion of pathway-biased signaling. [13] [11]

Implications for Drug Discovery and Therapeutic Targeting

The deep structural and mechanistic understanding of GPCRs has profoundly impacted modern pharmacology. The trend is moving beyond simple agonists and antagonists toward sophisticated modulators. Allosteric modulators bind to sites distinct from the orthosteric (endogenous ligand) site, offering potential for greater subtype selectivity and reduced side effects. [11] [8] Furthermore, the concept of biased agonism (or functional selectivity)—where a ligand preferentially activates a subset of the receptor's signaling pathways—is a major frontier. [12] [13] For example, G protein-biased μ-opioid receptor agonists like oliceridine aim to provide analgesia while minimizing the β-arrestin-mediated side effects of respiratory depression and constipation. [12]

Emerging strategies include the design of bitopic ligands that simultaneously engage both the orthosteric and an allosteric site, and the exploration of intracellular binding sites for "molecular glues" that can stabilize specific receptor-transducer interfaces. [11] [8] As of late 2023, over 550 structures of GPCR-signaling complexes are available in the Protein Data Bank, providing an unprecedented roadmap for structure-based drug design and the development of next-generation therapeutics with improved efficacy and safety profiles. [8]

Ionotropic receptors, also known as ligand-gated ion channels (LICs, LGIC), represent a critical class of transmembrane proteins that directly mediate rapid signal transduction throughout the nervous system by converting chemical neurotransmitter signals into electrical impulses at synapses [17]. These receptors function as molecular machines that open their intrinsic ion-conducting pores in response to binding specific chemical messengers (ligands), thereby permitting selective ion flux across cell membranes within milliseconds [18]. This direct coupling of ligand binding to channel gating enables the exceptional speed of synaptic transmission that underpins neural communication, contrasting with the slower metabotropic receptors that operate through second messenger systems [18].

Within the broader context of drug-receptor interactions research, ionotropic receptors represent prime pharmacological targets for therapeutic intervention in neurological and psychiatric disorders [19]. Their well-defined binding sites, diverse subunit compositions, and sophisticated allosteric regulation mechanisms offer multiple avenues for drug discovery and development [20]. This technical guide comprehensively examines the structural classification, gating mechanisms, research methodologies, and therapeutic targeting of ionotropic receptors, providing a foundation for ongoing research into these crucial signaling molecules.

Structural Classification and Functional Properties

Ionotropic receptors are classified into three evolutionarily distinct superfamilies based on their structural architecture and activation mechanisms: the cys-loop receptors, ionotropic glutamate receptors, and ATP-gated channels [17]. Despite functional similarities, these superfamilies exhibit unique structural characteristics that define their gating kinetics, ion selectivity, and regulatory properties.

Cys-Loop Receptors

The cys-loop receptor superfamily is named for a characteristic disulfide bond between two cysteine residues in the extracellular N-terminal domain [17]. These receptors are pentameric assemblies with each subunit containing four transmembrane helices (TMSs) that constitute the transmembrane domain, and an extracellular, beta sheet sandwich-type, N-terminal ligand-binding domain [17]. Cys-loop receptors are further subdivided into cationic and anionic types based on their ion selectivity, which determines whether their activation produces excitatory or inhibitory responses [17].

Table 1: Cationic Cys-Loop Receptors

| Type | Class | IUPHAR Protein Name | Gene | Ion Selectivity | Primary Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serotonin | 5-HT3 | 5-HT3A, 5-HT3B, 5-HT3C, 5-HT3D, 5-HT3E | HTR3A, HTR3B, HTR3C, HTR3D, HTR3E | Cations (Na+, K+) | Excitatory |

| Nicotinic acetylcholine | nAChR | α1-α10, β1-β4, γ, δ, ε | CHRNA1-CHRNA10, CHRNB1-CHRNB4, CHRNG, CHRND, CHRNE | Cations (Na+, K+, Ca2+) | Excitatory |

| Zinc-activated ion channel | ZAC | ZACN | ZACN | Cations | Excitatory |

| Valeriandoid F | Valeriandoid F, CAS:1427162-60-4, MF:C23H34O9, MW:454.516 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals | ||

| Fmoc-MMAF-OMe | Fmoc-MMAF-OMe, MF:C55H77N5O10, MW:968.2 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Table 2: Anionic Cys-Loop Receptors

| Type | Class | IUPHAR Protein Name | Gene | Ion Selectivity | Primary Effect |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GABAA | Alpha, Beta, Gamma, etc. | α1-α6, β1-β3, γ1-γ3, etc. | GABRA1-GABRA6, GABRB1-GABRB3, GABRG1-GABRG3, etc. | Anions (Cl-) | Inhibitory |

| Glycine | Alpha, Beta | α1-α4, β | GLRA1-GLRA4, GLRB | Anions (Cl-) | Inhibitory |

The prototypic ligand-gated ion channel is the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR), which consists of a pentamer of protein subunits (typically ααβγδ) with two binding sites for acetylcholine [17]. When acetylcholine binds at the interface of each alpha subunit, it induces a conformational change that twists the T2 helices, moving leucine residues that block the pore out of the channel pathway, thereby widening the constriction in the pore from approximately 3Å to 8Å to allow ions to pass through [17]. This pore opening permits Na+ ions to flow down their electrochemical gradient into the cell, and with sufficient channel activation, this inward flow of positive charges depolarizes the postsynaptic membrane sufficiently to initiate an action potential [17].

Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors

Ionotropic glutamate receptors (iGluRs) constitute a structurally distinct family that mediates the majority of excitatory neurotransmission in the central nervous system [21]. These receptors form tetrameric assemblies with each subunit consisting of four discrete domains: an extracellular amino-terminal domain (ATD) involved in tetramer assembly, an extracellular ligand-binding domain (LBD) that binds glutamate, a transmembrane domain (TMD) that forms the ion channel, and an intracellular carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) responsible for receptor localization and regulation [21] [22].

Table 3: Ionotropic Glutamate Receptor Classification

| Type | Class | IUPHAR Protein Name | Gene | Kinetic Properties | Calcium Permeability |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMPA | GluA | GluA1-GluA4 | GRIA1-GRIA4 | Fast activation and desensitization | GluA2-lacking: Ca2+ permeable |

| Kainate | GluK | GluK1-GluK5 | GRIK1-GRIK5 | Intermediate kinetics | Variable |

| NMDA | GluN | GluN1, GluN2A-GluN2D, GluN3A-GluN3B | GRIN1, GRIN2A-GRIN2D, GRIN3A-GRIN3B | Slow kinetics, voltage-dependent | Highly Ca2+ permeable |

The iGluR architecture exhibits a unique 2-fold symmetry throughout the extracellular and transmembrane domains, which is exceptional for tetrameric ion channels [21]. The transmembrane domain has an inverted orientation in the membrane compared to voltage-gated ion channels and consists of three transmembrane helices (M1, M3, and M4) and a re-entrant intracellular loop (M2) between helices M1 and M3 [21]. The M3 segments line the extracellular portion of the ion channel pore, while M1 and M4 surround M3s and form the ion channel periphery [21].

The NMDA receptor subtype exhibits particularly complex gating properties, functioning as a coincidence detector that requires both glutamate binding and postsynaptic depolarization to relieve voltage-dependent Mg2+ block, thereby enabling calcium influx that is essential for synaptic plasticity processes including long-term potentiation (LTP) and long-term depression (LTD) [18].

Gating Mechanisms and Signal Transduction

The process by which ionotropic receptors convert ligand binding into ion channel opening represents a fundamental problem in structural biology. Recent advances in cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and X-ray crystallography have provided unprecedented insights into the conformational changes underlying receptor gating.

Structural Mechanisms of Gating

Ionotropic receptors exist in multiple functional states—closed, open, and desensitized—with transitions between these states governed by both ligand binding and allosteric modulation [21]. For iGluRs, the LBD forms a clamshell-like structure that closes around the bound agonist, creating tension in the linkers connecting the LBD to the transmembrane domain [22]. This tension is thought to pull on the M3 helices that form the channel gate, leading to a rotation and separation of these helices that opens the ion conduction pathway [21].

The gating process can be described by a simplified kinetic model that includes closed (C), pre-active (P), open (O), and desensitized (D) states [21]. Agonist binding (C to CA transition) is followed by conformational changes that place the receptor in a pre-active state (P), from which it can either convert into a conducting state (O) or adopt an active but nonconducting desensitized state (D) [21]. The transition from PA to OA is much faster than the PA to DA transition and defines the fast, submillisecond timescale rise in inward current that signifies receptor activation [21].

Diagram 1: Ionotropic Receptor Gating Cycle. This diagram illustrates the simplified kinetic model of ionotropic receptor gating, showing transitions between closed (C), agonist-bound closed (CA), pre-active (P), open (O), and desensitized (D) states.

Ion Permeation and Selectivity

The ion selectivity of ligand-gated channels determines their physiological effects, with excitatory receptors generally permeable to cations (Na+, K+, and sometimes Ca2+) and inhibitory receptors generally permeable to anions (Cl-) [18]. Excitatory ionotropic receptors are nonselective cation channels with a reversal potential (E_rev) around 0 mV, while inhibitory receptors are anion selective with a reversal potential of -70 to -30 mV [18].

For the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, the opening of the channel pore allows simultaneous passage of Na+, Ca2+, and K+ ions, with the net effect of moving the membrane potential close to 0 mV (approximately halfway between the equilibrium potential of Na+ and the equilibrium potential of K+) [23]. This represents a large depolarization from the typical resting potential of -70 mV and is typically sufficient to stimulate an action potential or activate voltage-gated Ca2+ channels at the active zone of a synapse [23].

In contrast, GABAA receptor activation allows the passage of chloride (Cl-) ions, generally moving the membrane potential toward ECl (the equilibrium potential for Cl-, which is generally near the resting potential) [23]. This "clamps" the membrane potential at ECl and prevents it from rising to threshold potential, thereby producing neuronal inhibition [23].

Experimental Methodologies for Ionotropic Receptor Research

Structural Biology Approaches

Understanding ionotropic receptor function at the molecular level requires detailed structural information, which has been obtained through multiple complementary techniques:

X-ray Crystallography: This technique has provided high-resolution structures of isolated domains (ATD and LBD) of iGluRs, revealing the atomic details of ligand binding and domain arrangements [22]. For example, over 268 crystal structures of LBDs of various subunits from all major iGluR subclasses in complex with agonists, antagonists, partial agonists, and allosteric modulators are available [22]. The first structure of a full-length iGluR (AMPAR subtype GluA2) in the closed, competitive antagonist-bound state was determined using crystallography [21].

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): Recent advances in cryo-EM have enabled determination of full-length iGluR structures in various functional states, including activated, glutamate-bound AMPA receptors in conducting states and conformational changes during desensitization [21]. This technique has been particularly valuable for visualizing heterotetrameric NMDA receptors, which were once considered overwhelmingly challenging targets for structural biology [22]. Cryo-EM studies of the GluA2-GSG1L complex in the presence of antagonists have provided the most complete closed state iGluR channel structure to date [21].

Electrophysiological Techniques: Patch-clamp recording, particularly in whole-cell and single-channel configurations, provides functional data complementary to structural studies. Whole-cell patch-clamp currents in response to prolonged application of agonist illustrate three major iGluR gating functions: activation, desensitization, and deactivation [21]. Single-channel recordings reveal multiple conductance levels whose occupancy depends on agonist type and concentration, reflecting different extents of pore opening and activation states for each of the four contributing receptor subunits [21].

Table 4: Key Structural Studies of Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors

| Receptor Type | Technique | State | Resolution | Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GluA2 AMPAR | X-ray Crystallography | Antagonist-bound (closed) | 3.6 Ã… | First full-length iGluR structure; revealed Y-shaped architecture and domain organization [22] |

| GluA2 AMPAR | Cryo-EM | Agonist-bound (pre-active) | 4.0-4.5 Ã… | Showed shortened vertical dimension with ATD and LBD closer together [21] |

| GluA2-GSG1L Complex | Cryo-EM | Antagonist-bound (closed) | 4.6 Ã… (TMD ~4 Ã…) | Most complete closed state iGluR channel structure [21] |

| GluN1/GluN2B NMDA | Cryo-EM | Antagonist-bound | 4.0 Ã… | First heterotetrameric NMDAR structure; revealed allosteric sites [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 5: Key Research Reagents for Ionotropic Receptor Studies

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Research | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agonists | Glutamate, Acetylcholine, GABA, Glycine | Activate receptors by binding to orthosteric sites | Receptor activation studies, functional assays |

| Competitive Antagonists | ZK200775 (AMPAR), D-AP5 (NMDAR) | Bind orthosteric site without activation, block agonist binding | Defining receptor specificity, structural studies of closed states |

| Allosteric Modulators | Cyclothiazide (AMPAR), Ifenprodil (NMDAR) | Bind to alternative sites to potentiate or inhibit receptor function | Studying gating mechanisms, therapeutic development |

| Channel Blockers | Memantine (NMDAR), PCP (NMDAR) | Bind within ion channel pore to physically block ion flux | Investigating pore properties, therapeutic applications |

| subunit-Selective Compounds | α-Bungarotoxin (nAChR), NASPM (Ca2+-permeable AMPAR) | Specifically target receptor subtypes | Determining subunit composition, selective manipulation |

| Tagged Antibodies | Anti-GluN1, Anti-GABAAR β-subunit | Label receptors for localization and quantification | Immunohistochemistry, Western blot, surface expression |

| Auxiliary Subunits | GSG1L, Stargazin | Modulate receptor trafficking and gating | Studying native receptor complexes, regulatory mechanisms |

| RSV604 racemate | 1-(2-fluorophenyl)-3-(2-oxo-5-phenyl-1,3-dihydro-1,4-benzodiazepin-3-yl)urea | Bench Chemicals | |

| Tunicamycin V | Tunicamycin V, CAS:66054-36-2, MF:C38H62N4O16, MW:830.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Diagram 2: Experimental Approaches for Ionotropic Receptor Research. This diagram categorizes the major methodological approaches used to study the structure, function, and pharmacology of ionotropic receptors.

Pathophysiological Implications and Therapeutic Targeting

Dysfunction of ionotropic receptor signaling is implicated in numerous neurological and psychiatric disorders, making these receptors prominent targets for therapeutic intervention [18]. Aberrant expression or function of neuronal ion channels, including ionotropic neurotransmitter receptors, is a major epileptogenic factor, with channelopathies favoring increased amplitude or duration of depolarizing currents or reduced hyperpolarizing currents, contributing to neuronal hyper-excitability and idiopathic epilepsies [18].

Excitotoxicity and Neurodegenerative Disorders

Excitotoxicity resulting from overactivation of glutamate ionotropic receptors is considered one of the main causes of neuronal damage in acute and chronic neurodegenerative disorders [18]. Overstimulation of NMDA receptors floods the cytoplasm with calcium, while AMPA receptor stimulation is necessary to depolarize the neuronal membrane, allowing NMDA channels to open [18]. This pathological process is implicated in Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, Huntington's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and stroke-related damage [18].

The NMDA receptor dysfunction is particularly significant in cognitive deficits associated with neuropsychiatric disorders and neurodegenerative diseases, including Alzheimer's disease and schizophrenia [18]. Anti-NMDA receptor encephalitis represents an autoimmune disorder characterized by autoantibodies targeting the NMDA receptor, leading to psychiatric and neurologic symptoms, including seizures and amnesia [18].

Pharmacological Interventions

Several therapeutic strategies target ionotropic receptors for symptomatic and disease-modifying benefits:

NMDA Receptor Antagonists: Memantine, an uncompetitive NMDA receptor antagonist, is the only FDA-approved NMDA receptor antagonist indicated for moderate-to-severe Alzheimer's disease, showing modest but statistically significant improvements in cognition and functional endpoints [20] [18]. Memantine functions through a mechanism called membrane-to-channel inhibition (MCI), where membrane-associated drug molecules can transit into the channel through a fenestration within the NMDAR upon receptor activation [20].

GABAA Receptor Modulators: Benzodiazepines and barbiturates enhance GABAA receptor function through allosteric binding sites, producing anxiolytic, sedative, and anticonvulsant effects [17]. These drugs potentiate GABA-induced chloride currents without directly activating the receptor themselves.

Nicotinic Receptor Agonists: Varenicline, a partial agonist at α4β2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, is used for smoking cessation by reducing nicotine craving and withdrawal symptoms while providing limited activation of the reward system [17].

The evolutionary history of ionotropic receptors provides important context for understanding their roles in human physiology and disease. Comparative genomic analyses reveal that the Human-Cnidaria common ancestor displayed a massive emergence of neuroexclusive genes, mainly ionotropic receptors, which might have been crucial to the evolution of synapses [24]. This evolutionary perspective highlights the fundamental conservation of these signaling mechanisms while also revealing opportunities for developing species-specific pharmacological interventions.

Ionotropic receptors represent sophisticated molecular machines that directly convert chemical signals into electrical impulses with remarkable speed and precision. Their complex modular architecture, diverse subunit composition, and dynamic gating mechanisms enable the nuanced regulation of synaptic transmission essential for neural computation, learning, and memory. Ongoing structural biology efforts continue to reveal new insights into the conformational changes underlying receptor activation, desensitization, and allosteric modulation.

From a drug-receptor interactions perspective, ionotropic receptors offer multiple targeting opportunities through orthosteric sites, allosteric regulatory sites, and channel-blocking mechanisms. The continued development of subtype-selective compounds holds promise for more effective therapies with reduced side effects for neurological and psychiatric disorders. As research methodologies advance, particularly in cryo-EM and computational modeling, our understanding of these crucial signaling molecules will continue to deepen, enabling more sophisticated therapeutic interventions for conditions involving disrupted synaptic transmission.

Kinase-linked receptors and nuclear receptors represent two paramount classes of signaling molecules that transduce extracellular and intracellular cues into precise transcriptional programs, thereby governing essential cellular processes such as growth, differentiation, and metabolism. This technical guide delineates the fundamental structures, activation mechanisms, and downstream signaling cascades associated with these receptors, emphasizing their roles in gene regulation and cellular proliferation. Within the broader thesis of drug receptor interactions, we explore the profound therapeutic implications of targeting these pathways, including the management of cancer, metabolic diseases, and inflammatory disorders. The whitepaper synthesizes current research findings, provides detailed experimental methodologies, and visualizes complex signaling networks, offering a comprehensive resource for researchers and drug development professionals engaged in signal transduction pathways research.

Cell-cell communication and responses to environmental stimuli are mediated by a diverse array of receptor families, among which kinase-linked receptors and nuclear receptors constitute two major classes with distinct yet sometimes interconnected signaling mechanisms. Kinase-linked receptors, primarily located on the cell surface, include receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs) which initiate complex intracellular phosphorylation cascades in response to growth factors and hormones [25]. These signals ultimately reach the nucleus to modulate gene expression, influencing critical processes like cell cycle progression and survival. In contrast, nuclear receptors reside within the cell and function as ligand-activated transcription factors that directly bind DNA and regulate gene transcription in response to lipophilic hormones such as steroids, thyroid hormone, and vitamins [3] [26].

The signaling timelines and biological outcomes differ significantly between these receptor classes. RTK signaling typically initiates within seconds to minutes, culminating in transcriptional changes over hours. Nuclear receptor signaling, while sometimes involving non-genomic effects, primarily regulates transcription over hours to days, resulting in sustained changes to cellular phenotype [25]. Despite these differences, crosstalk between RTK and nuclear receptor pathways creates integrated signaling networks that coordinate complex physiological responses, with dysregulation in these networks contributing to various disease states, including cancer, metabolic syndrome, and inflammatory disorders [27] [26].

Kinase-Linked Receptors: Structure and Activation Mechanisms

Structural Organization and Classification

Kinase-linked receptors are transmembrane proteins that transmit signals from extracellular ligands to the cell interior through their intrinsic enzymatic activity. The most prominent subgroup, receptor tyrosine kinases (RTKs), comprises large intrinsic membrane proteins with a single membrane-spanning segment. These receptors function as dimers, either constitutively or induced by ligand binding [25]. The human genome encodes approximately 90 tyrosine kinases, with over half classified as RTKs [25]. Structurally, RTKs contain an extracellular ligand-binding domain, a transmembrane helix, and an intracellular domain possessing tyrosine kinase activity.

Ligands for RTKs are typically polypeptide hormones and growth factors such as epidermal growth factor (EGF), nerve growth factor (NGF), vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), and insulin [25]. Upon ligand binding to the extracellular domain, RTKs undergo conformational changes that stimulate their tyrosine kinase activity located in the cytoplasmic portion, initiating intracellular signaling cascades.

Activation Mechanism and Autophosphorylation

The activation mechanism of RTKs involves ligand-induced dimerization, bringing two receptor subunits into close proximity [25]. In this dimeric configuration, each subunit phosphorylates tyrosine residues in its partner subunit through a process termed auto-phosphorylation [25]. These phosphorylation events occur in specific regions of the intracellular domain and serve two crucial functions: they enhance the kinase activity of the receptor itself, and create docking sites for intracellular signaling proteins containing phosphotyrosine-binding domains such as SH2 domains.

This nucleation of protein complexes on the phosphorylated tyrosine residues of activated RTKs represents the primary mechanism for initiating downstream signaling pathways [25]. The specific pattern of phosphorylation determines which signaling molecules are recruited, thus defining the cellular response to receptor activation.

Table 1: Major Receptor Tyrosine Kinase Families and Their Ligands

| RTK Family | Representative Members | Key Ligands | Primary Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| ErbB | EGFR (ERBB1), HER2 (ERBB2) | EGF, TGF-α | Cell proliferation, differentiation |

| Insulin Receptor | INSR, IGF1R | Insulin, IGF-1 | Metabolic regulation, growth |

| NGFR | TrkA, TrkB | NGF, BDNF | Neuronal survival, plasticity |

| VEGFR | VEGFR1, VEGFR2 | VEGF-A, VEGF-B | Angiogenesis, vascular permeability |

| FGFR | FGFR1, FGFR2 | FGF-1, FGF-2 | Development, tissue repair |

Nuclear Receptors: Structure and Classification

Structural Domains and Functional Organization

Nuclear receptors (NRs) comprise a superfamily of 48 members in the human genome that function as ligand-dependent transcription factors [3] [28]. These receptors share a conserved modular structure consisting of several functional domains:

- N-terminal domain (NTD): Contains the activation function 1 (AF-1) region, which participates in transcriptional activation and interacts with coregulatory proteins [3].

- DNA-binding domain (DBD): A highly conserved region containing two zinc fingers that mediate sequence-specific binding to hormone response elements (HREs) in target gene promoters [3].

- Hinge region: Provides flexibility between the DBD and LBD.

- Ligand-binding domain (LBD): Mediates ligand binding, receptor dimerization, and contains the activation function 2 (AF-2) region that recruits transcriptional co-regulators [3].

This modular architecture enables nuclear receptors to sense intracellular hormonal and metabolic signals and directly translate these signals into changes in gene expression programs.

Classification Systems for Nuclear Receptors

Nuclear receptors are classified based on their ligand specificity, dimerization properties, and DNA binding mechanisms:

Type I Nuclear Receptors (Steroid receptors): Include estrogen receptor (ER), androgen receptor (AR), progesterone receptor (PR), glucocorticoid receptor (GR), and mineralocorticoid receptor (MR). These receptors typically reside in the cytoplasm complexed with heat shock proteins (HSPs) in the absence of ligand. Upon ligand binding, they dissociate from HSPs, form homodimers, translocate to the nucleus, and bind to inverted repeat HREs [3] [26].

Type II Nuclear Receptors (Non-steroid receptors): Include thyroid hormone receptors (TRα and TRβ), retinoic acid receptors (RARα, β, γ), vitamin D receptor (VDR), and peroxisome proliferator-activated receptors (PPARα, β, γ). These receptors typically reside in the nucleus bound to DNA even in the absence of ligand, often forming heterodimers with retinoid X receptors (RXR) and binding to direct repeat HREs [3] [26].

Type III and IV Receptors: Include orphan receptors whose endogenous ligands remain unknown or receptors that function as monomers [3] [26].

Table 2: Major Nuclear Receptor Classes and Their Characteristics

| Receptor Type | Representative Members | Endogenous Ligands | DNA Binding Pattern |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type I (Steroid) | ER, AR, GR, MR | Steroid hormones | Homodimers on inverted repeats |

| Type II (Non-steroid) | TR, RAR, VDR, PPAR | Thyroid hormone, retinoic acid, vitamin D | RXR heterodimers on direct repeats |

| Type III (Orphan) | HNF4A, NR4A1 | Unknown or fatty acids | Homodimers or monomers |

| Type IV (Monomeric) | SF1, LRH1 | Phospholipids | Monomers on extended sites |

Signaling Cascades and Gene Regulation Mechanisms

Major Kinase-Linked Receptor Signaling Pathways

Ras/ERK Pathway (MAPK Cascade)

The Ras/ERK pathway represents a quintessential kinase signaling cascade that relays signals from activated RTKs to the nucleus. The signaling sequence involves:

- RTK activation by growth factors (e.g., EGF) leads to autophosphorylation and recruitment of the adaptor protein Grb2 [29] [25].

- Grb2 recruits the guanine nucleotide exchange factor SOS to the membrane, where it activates Ras by promoting GDP to GTP exchange [29] [25].

- Activated Ras triggers a three-tiered kinase cascade: Raf (MAPKKK) → MEK (MAPKK) → ERK (MAPK) [29] [25].

- ERK translocates to the nucleus and phosphorylates transcription factors such as Elk-1, c-Fos, and c-Myc, thereby regulating genes controlling cell cycle progression and proliferation [29].

This cascade demonstrates the principle of signal amplification, where a single activated receptor can ultimately influence the phosphorylation of hundreds of substrates [29].

PI3K/Akt Pathway

The PI3K/Akt pathway represents another critical signaling route from RTKs:

- Activated RTKs recruit and activate phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) either directly or through adaptor proteins like IRS1 in insulin signaling [29] [25].

- PI3K phosphorylates the membrane lipid PIP₂ to generate PIP₃ [29].

- Akt is recruited to the membrane by PIP₃ and phosphorylated/activated by PDK1 and mTORC2 [29].

- Activated Akt controls both cytoplasmic functions (e.g., GLUT4 translocation to the membrane for glucose uptake) and nuclear functions (e.g., regulation of transcription factors like FoxO1) [29] [25].

This pathway is crucial for metabolic regulation and cell survival, with its deregulation frequently observed in cancer and metabolic disorders.

Nuclear Receptor Mechanisms of Gene Regulation

Nuclear receptors regulate gene expression through a multi-step process:

Ligand binding: Hydrophobic ligands diffuse across the plasma membrane and bind to the LBD of nuclear receptors, inducing conformational changes [3] [26].

Nuclear translocation and DNA binding: For Type I receptors, ligand binding triggers dissociation from chaperone proteins, nuclear translocation, and binding to specific DNA sequences called hormone response elements (HREs) [3] [26]. Type II receptors are typically already nuclear and DNA-bound.

Recruitment of co-regulators: Ligand-bound receptors recruit co-activator complexes (e.g., histone acetyltransferases) that modify chromatin structure and make target genes more accessible [3] [26].

Assembly of transcriptional machinery: The receptor-coactivator complexes recruit RNA polymerase II and general transcription factors to initiate transcription of target genes [3] [25].

The specific HRE sequence, cellular context, and recruited co-regulators determine which genes are activated or repressed by a given nuclear receptor.

Figure 1: Kinase-Linked Receptor Signaling Cascade. This diagram illustrates the sequential activation of signaling components from growth factor binding to gene expression regulation through the MAPK pathway.

Figure 2: Nuclear Receptor-Mediated Gene Regulation. This diagram illustrates the pathway from ligand binding to transcription activation through nuclear receptor binding to hormone response elements.

Experimental Approaches for Studying Receptor Function

Investigating Kinase-Linked Receptors

Kinase Activity Profiling

Comprehensive approaches to map kinase signaling networks have been developed, including large-scale screening of kinase-substrate relationships. A recent study from St. Jude Children's Research Hospital exemplifies this approach:

- Experimental Objective: Systematically identify kinases capable of phosphorylating the RNA polymerase II C-terminal domain (CTD) at specific positions [30].

- Methodology:

- Expressed and purified 427 human kinases

- Performed in vitro kinase assays with synthetic RNA polymerase II CTD peptides

- Utilized phospho-specific antibodies and mass spectrometry to identify phosphorylation sites

- Validated findings using immunofluorescence and chromatin immunoprecipitation [30]

- Key Finding: Identified 117 kinases with specific positional preferences, including unexpected nuclear functions for cell surface receptors like EGFR [30].

Signal Transduction Analysis

To study downstream signaling cascades:

- Phosphoprotein Analysis: Western blotting with phospho-specific antibodies to monitor activation states of pathway components (e.g., phospho-ERK, phospho-Akt) [29].

- Pathway Reporter Assays: Utilization of luciferase-based reporters (e.g., GloSensor cAMP biosensor) to quantify second messenger production or pathway activation in live cells [13].

- Protein-Protein Interaction Studies: Co-immunoprecipitation and proximity ligation assays to characterize signaling complexes formation [27].

Analyzing Nuclear Receptor Function

Transcriptional Activation Assays

Standard protocols for assessing nuclear receptor activity include:

Luciferase Reporter Assays:

- Clone hormone response elements (HREs) upstream of a minimal promoter driving luciferase expression

- Cotransfect receptor expression plasmid and reporter construct into recipient cells

- Treat with candidate ligands for 24-48 hours

- Measure luciferase activity as a readout of receptor activation [3]

Gene Expression Profiling:

Receptor-Ligand Interaction Studies

- Ligand Binding Assays: Use of radiolabeled ligands (e.g., [³H]-dexamethasone for GR) in competitive binding experiments to determine binding affinities (Kd values) [3].

- X-ray Crystallography: Determination of receptor-ligand binding domain structures to understand interaction mechanisms and guide drug design [3] [26].

- Cellular Localization Studies: Immunofluorescence staining to monitor receptor translocation from cytoplasm to nucleus upon ligand treatment [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Studying Kinase-Linked and Nuclear Receptors

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications | Key Functions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinase Inhibitors | Selumetinib (MEK inhibitor), Imatinib (BCR-Abl inhibitor) | Pathway inhibition studies, therapeutic screening | Target specific kinases to block downstream signaling and assess functional outcomes |

| Nuclear Receptor Ligands | Rosiglitazone (PPARγ agonist), Tamoxifen (ER modulator), Obeticholic acid (FXR agonist) | Receptor activation studies, gene regulation analysis, drug development | Activate or inhibit specific NRs to study their functions and therapeutic potential |

| Pathway Reporters | GloSensor cAMP biosensor, ERK translocation biosensors, PRE/TRE-luciferase reporters | Real-time signaling monitoring, high-throughput compound screening | Visualize and quantify pathway activation in live cells or after treatment |

| Phospho-Specific Antibodies | Anti-phospho-ERK, Anti-phospho-Akt, Anti-phospho-tyrosine | Western blotting, immunofluorescence, flow cytometry | Detect activation states of signaling molecules with high specificity |

| Protein Interaction Tools | Co-IP kits, Proximity ligation assay reagents, Yeast two-hybrid systems | Mapping signaling complexes, identifying novel interactions | Characterize protein-protein interactions in signaling pathways |

| Gene Expression Analysis | RNA-seq kits, qPCR reagents, ChIP kits | Transcriptome profiling, target gene validation, chromatin binding studies | Analyze gene expression changes and direct transcriptional targets |

| ARM1 | ARM1, CAS:1049743-03-4; 68729-05-5, MF:C16H14N2S, MW:266.36 | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Mogroside IIe | Mogroside IIe, CAS:88901-38-6, MF:C42H72O14, MW:801.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Crosstalk Between Signaling Pathways

Receptor Transactivation Mechanisms

Significant crosstalk occurs between kinase-linked receptors and nuclear receptors, creating interconnected signaling networks:

RTK-Nuclear Receptor Interactions: Computational analyses of human signaling networks have identified numerous interactions between RTKs and nuclear receptors. For example, the EGFR-ESR1 (estrogen receptor) interaction has been experimentally validated, representing a key point of crosstalk between growth factor and hormonal signaling pathways [27].

GPCR-RTK Transactivation: G protein-coupled receptors can transactivate RTKs through proteolytic cleavage of RTK ligands (e.g., HB-EGF by ADAM17) or through intracellular kinase-mediated activation (e.g., Fyn-mediated TrkB activation) [25].

Nuclear Kinase Functions: Recent research has revealed unexpected nuclear roles for traditional signaling kinases. For instance, the cell-surface tyrosine kinase EGFR can translocate to the nucleus and directly phosphorylate RNA polymerase II, providing a more immediate mechanism for regulating gene transcription in response to extracellular signals [30].

Integrated Signaling in Disease

The crosstalk between signaling pathways has profound implications for disease mechanisms and treatment:

Cancer: In breast cancer, complex interactions between steroid receptors (ER and PR) and growth factor receptor signaling govern disease progression and therapeutic response [27]. The presence of untethered kinases in the nucleus of aggressive cancers can disrupt transcriptional programs, suggesting new therapeutic vulnerabilities [30].

Metabolic Disease: Nuclear receptors such as PPARγ, which is targeted by thiazolidinedione drugs for diabetes, integrate metabolic and inflammatory signals [26] [28]. The therapeutic effects of PPARγ activation involve both direct transcriptional regulation and modulation of kinase signaling pathways.

Drug Resistance: Cross-talk between signaling pathways often underlies resistance to targeted therapies. For example, resistance to RAF inhibitors in melanoma frequently involves rewiring of both MAPK and PI3K/AKT pathways [29].

Therapeutic Applications and Drug Development

Clinically Targeted Receptors

Both kinase-linked receptors and nuclear receptors represent important drug targets across diverse disease areas:

Kinase-Targeted Therapies:

- EGFR inhibitors (e.g., erlotinib, gefitinib) for non-small cell lung cancer

- BCR-Abl inhibitors (e.g., imatinib) for chronic myeloid leukemia

- Multiple kinase inhibitors (e.g., sorafenib, regorafenib) for various cancers [29]

Nuclear Receptor-Targeted Therapies:

- PPARγ agonists (e.g., pioglitazone, rosiglitazone) for type 2 diabetes [26] [28]

- Selective estrogen receptor modulators (e.g., tamoxifen, raloxifene) for breast cancer and osteoporosis [3]

- AR antagonists (e.g., enzalutamide) for prostate cancer [3]

- FXR agonists (e.g., obeticholic acid) for metabolic liver diseases [26]

Emerging Approaches in Drug Discovery

Recent advances in receptor-targeted drug development include:

Biased Signaling Modulation: Development of ligands that preferentially activate specific downstream pathways while avoiding others to enhance therapeutic efficacy and reduce side effects. This approach is being actively pursued for both GPCRs and nuclear receptors [13].

Selective Nuclear Receptor Modulators: Development of tissue-selective receptor modulators that activate receptors in desired tissues while antagonizing them in tissues where activation would cause side effects [26].

Intracellular Allosteric Modulators: Identification of compounds that bind to allosteric sites on intracellular domains of receptors to achieve greater specificity [13].

Combination Therapies: Strategic targeting of multiple receptors in interconnected pathways to enhance efficacy and overcome resistance mechanisms [29] [26].

Kinase-linked receptors and nuclear receptors represent sophisticated signaling systems that translate extracellular and intracellular cues into precise transcriptional responses governing cell growth, metabolism, and differentiation. While operating through distinct mechanisms—with kinase-linked receptors utilizing sequential phosphorylation cascades and nuclear receptors functioning as direct ligand-activated transcription factors—these systems exhibit extensive crosstalk that enables integrated control of cellular physiology.

Future research directions will likely focus on several key areas: First, comprehensively mapping the complex interaction networks between different receptor families to understand systems-level regulation of cellular functions. Second, exploiting structural biology and computational approaches to design increasingly specific receptor modulators with tailored signaling properties. Third, developing strategies to achieve tissue-selective receptor modulation to enhance therapeutic efficacy while minimizing side effects. Finally, advancing our understanding of receptor dysregulation in disease states to identify new therapeutic targets and overcome drug resistance mechanisms.

The continued elucidation of receptor mechanisms and their interconnections will undoubtedly yield novel insights into cellular regulation and provide new opportunities for therapeutic intervention across a spectrum of human diseases, from cancer to metabolic disorders. As research methodologies advance, particularly in areas such as structural biology, single-cell analysis, and artificial intelligence-assisted drug design, our ability to precisely target these critical signaling molecules will continue to improve, offering new hope for patients with diseases driven by receptor pathway dysregulation.

The therapeutic effects of drugs are fundamentally governed by their precise interactions with specific cellular targets, primarily receptors. These drug-receptor interactions form the cornerstone of pharmacology, dictating the efficacy, safety, and specificity of therapeutic agents [19]. At the core of understanding these interactions are two indispensable drug properties: affinity, which describes the strength of binding between a drug and its receptor, and efficacy, which describes the ability of a drug to activate the receptor and produce a biological response once bound [31] [32]. These properties are not isolated; they are inextricably linked, a phenomenon known as the affinity-efficacy problem, wherein the binding of a ligand that induces a conformational change in its receptor depends on both its affinity for the receptor and its efficacy [33]. This comprehensive guide explores the principles of drug binding, framing them within the context of modern receptor theory and signal transduction research for an audience of scientists and drug development professionals.

Core Principles of Drug-Receptor Interactions

Affinity: The Strength of Binding

Affinity is the thermodynamic measure of the propensity of a drug to bind to a specific receptor. It is a system-independent constant, unique for each drug-receptor pair and determined by the structural complementarity between the drug and its receptor binding site [31] [19]. Numerically, affinity is most often quantified as the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd), which is the concentration of drug required to occupy 50% of the receptor population at equilibrium [32]. A lower Kd value signifies a higher binding affinity, meaning less drug is required to achieve a given level of receptor occupancy [32]. The binding of a drug to its receptor is governed by the law of mass action and can be described by a graded dose-binding curve, from which the Bmax (maximal binding capacity) and Kd can be derived [32].

Efficacy: The Capacity to Elicit a Response

Efficacy (or intrinsic efficacy) is the property of a drug that determines the magnitude of the biological effect produced after it binds to the receptor [31]. Unlike affinity, efficacy is a dimensionless term that cannot be measured directly and is typically expressed relative to a reference agonist [31]. In functional assays, efficacy is observed as the maximal response (Emax) that a drug can produce [32]. A drug with high intrinsic efficacy can fully activate a receptor, leading to a maximal system response, whereas a drug with lower intrinsic efficacy may only partially activate the receptor, producing a submaximal response even at full receptor occupancy [34]. According to the del Castillo-Katz mechanism, efficacy arises from the drug's ability to stabilize the active conformation of the receptor, facilitating its isomerization from an inactive (R) to an active (R*) state [33].

The Affinity-Efficacy Problem

A critical and often overlooked concept in pharmacology is the affinity-efficacy problem. Traditional receptor theory, as proposed by Stephenson, assumed that receptor occupancy and the resulting response were separable properties, with occupancy depending solely on affinity (KA) [33]. However, this framework is flawed for agonists. The del Castillo-Katz mechanism provides a more accurate model:

Here, a drug (A) binds to the inactive receptor (R) to form a complex (AR), which can then isomerize to an active state (AR). The equilibrium constant for binding is the microscopic affinity, KA, and the equilibrium constant for the isomerization is the efficacy, E [33]. Crucially, a standard agonist binding experiment does not distinguish between AR and AR; it measures the total bound complex. The concentration for half-maximal binding in such an experiment is not KA, but an effective equilibrium constant, Keff, where Keff = KA/(1+E) [33]. This demonstrates that the measured macroscopic affinity of an agonist depends on both its true microscopic affinity (KA) and its efficacy (E). Therefore, for any agonist that induces a conformational change, affinity and efficacy are fundamentally linked and cannot be separated by simple equilibrium binding measurements [33].

Potency: A Hybrid Parameter

Potency is a functional parameter that reflects the dose of a drug required to produce a given effect. It is typically reported as the EC50 (or ED50), the concentration (or dose) that elicits 50% of the maximal response [32]. Potency is a hybrid property influenced by both the drug's affinity and its intrinsic efficacy. A drug can be potent due to high affinity (binding strongly at low concentrations), high efficacy (producing a strong signal even with low occupancy), or a combination of both [32]. Consequently, potency is a critical parameter in drug development, as it dictates the dosing regimen, but it must be interpreted in the context of the underlying affinity and efficacy.

Table 1: Key Quantitative Parameters in Drug-Receptor Interactions

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Constant | Kd | Concentration for 50% receptor occupancy | Lower Kd = Higher Affinity |

| Maximal Binding | Bmax | Total density of available receptors | System-specific capacity |

| Half-Maximal Effective Concentration | EC50 | Concentration for 50% of maximal response | Lower EC50 = Greater Potency |

| Maximal Response | Emax | Greatest possible effect of a drug | Defines Intrinsic Efficacy |

The Agonist-Antagonist Spectrum

Drugs are classified based on their intrinsic efficacy and the resulting biological effects, forming a spectrum of activity from full activation to complete blockade of receptor function.

Agonists

Agonists are ligands that bind to a receptor and alter its state, resulting in a biological response [34]. They possess both affinity and positive intrinsic efficacy.

- Full Agonists: These ligands produce the maximal response that the biological system is capable of. They can often do this without occupying 100% of the receptors, a concept related to "spare receptors" [34].

- Partial Agonists: These ligands bind to the receptor but produce a submaximal response (lower Emax) even when occupying the entire receptor population. In a system with a full agonist present, a partial agonist will act as a competitive antagonist, as it competes for and occupies receptors without fully activating them [31] [34].

- Inverse Agonists: These ligands produce an effect opposite to that of a conventional agonist. This is only possible in receptor systems that exhibit constitutive activity (basal activity in the absence of any ligand). Inverse agonists possess negative intrinsic efficacy, stabilizing the receptor in its inactive form and reducing basal signaling [31] [34].

Antagonists

Antagonists bind to receptors but possess zero intrinsic efficacy. They produce no biological response themselves but prevent agonists from binding and activating the receptor [31] [35].

- Competitive Antagonists: These drugs bind reversibly to the same site as the agonist (the orthosteric site), competing for occupancy. Their effects can be overcome by increasing the concentration of the agonist, which shifts the agonist's dose-response curve to the right (decreased potency) without altering the Emax [35].

- Non-competitive Antagonists: These drugs bind irreversibly to the orthosteric site or, more commonly, bind to a distinct, allosteric site on the receptor. By acting at a different site, they inhibit the receptor's function regardless of the agonist concentration, typically leading to a depression of the agonist's Emax [35].

Allosteric Modulators

Allosteric modulators bind to a site on the receptor that is topographically distinct from the orthosteric (primary) agonist site. They alter the receptor's conformation, which can either enhance (positive allosteric modulators) or diminish (negative allosteric modulators) the receptor's sensitivity to the orthosteric agonist [35] [34]. Unlike orthosteric ligands, allosteric modulators typically have no effect on their own and require the presence of the orthosteric agonist to exert their effect.

Diagram 1: Agonist-Antagonist Spectrum. This diagram visualizes the continuum of intrinsic efficacy, from inverse agonists that suppress constitutive receptor activity to full agonists that produce a maximal response.

Experimental Protocols for Quantifying Drug Properties

Radioligand Binding Assays to Measure Affinity (Kd)

Purpose: To determine the affinity (Kd) and density (Bmax) of receptors for a specific ligand. Methodology:

- Membrane Preparation: Isolate cell membranes expressing the target receptor.

- Saturation Binding: Incubate a constant amount of membrane protein with increasing concentrations of a radioactively labeled ligand ( [1]H- or I-labeled).

- Separation and Measurement: Separate the bound radioligand from the free radioligand (e.g., by filtration or centrifugation). Measure the radioactivity in the bound fraction.

- Non-Specific Binding: Parallel incubations include a high concentration (e.g., 1000x Kd) of an unlabeled competitor to define non-specific binding. Specific binding is total binding minus non-specific binding.

- Data Analysis: Plot specific bound radioligand (y-axis) against the concentration of free radioligand (x-axis). The resulting hyperbolic curve is analyzed by non-linear regression to derive Bmax and Kd [31].

Functional Assays to Measure Efficacy (Emax) and Potency (EC50)

Purpose: To quantify the biological response (efficacy and potency) of an agonist in a cellular system. Methodology:

- System Selection: Choose a cell-based system (primary cells or cell line) that natively expresses or is transfected with the target receptor and has a measurable, relevant downstream response.

- Response Measurement: Treat cells with a range of concentrations of the test agonist. The measured response can be:

- Second Messenger Production: e.g., cAMP, Ca2+, IP3 (measured via ELISA, FRET, or fluorescent dyes).

- Protein Phosphorylation: e.g., ERK1/2 phosphorylation (measured via Western blot or immunoassays).

- Gene Reporter Assays: e.g., Luciferase activity under the control of a responsive promoter.

- Cell Growth or Cytotoxicity: for drugs targeting proliferation.

- Data Analysis: Plot the response (y-axis) against the logarithm of the agonist concentration (x-axis). The generated sigmoidal curve is fitted to determine the EC50 (potency) and the Emax (efficacy) [32].

Schild Analysis for Antagonist Characterization

Purpose: To determine the affinity (pA2/KB) of a competitive antagonist and confirm its mechanism of action. Methodology:

- Generate a control concentration-response curve for an agonist.

- Generate subsequent agonist concentration-response curves in the presence of several fixed, increasing concentrations of the antagonist.

- A competitive antagonist will produce a parallel rightward shift of the agonist curves without suppressing Emax.

- Plot the log(agonist dose ratio - 1) against the log(antagonist concentration). The x-intercept of the resulting Schild regression is the pA2 value, which is the negative log of the antagonist's dissociation constant (KB) [31].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Key Experiments

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Example Assays |