High-Throughput Screening: Modern Methods for Accelerating Drug Discovery from Compound Libraries

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies for profiling compound libraries in modern drug discovery.

High-Throughput Screening: Modern Methods for Accelerating Drug Discovery from Compound Libraries

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of high-throughput screening (HTS) methodologies for profiling compound libraries in modern drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles of HTS and compound library design, details advanced methodological applications from ultra-high-throughput screening to functional genomics, and offers practical troubleshooting and optimization strategies to enhance data quality. Furthermore, it covers rigorous validation techniques and comparative analyses of different screening approaches. Aimed at researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this resource synthesizes current knowledge to guide the effective implementation of HTS for identifying novel therapeutic hits and leads.

The Building Blocks: Understanding HTS and Compound Library Fundamentals

Defining High-Throughput and Ultra-High-Throughput Screening (HTS/uHTS)

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is an automated drug discovery technique that enables researchers to rapidly conduct hundreds of thousands to millions of biological, chemical, or pharmacological tests in parallel [1] [2]. This method is primarily used to identify "hits" – compounds, antibodies, or genes that modulate a specific biomolecular pathway – which then serve as starting points for drug design and development [1]. The core infrastructure enabling HTS includes robotics, data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors that work together to minimize manual intervention and maximize testing efficiency [1].

Ultra-High Throughput Screening (uHTS) represents an advanced evolution of HTS, with screening capabilities that exceed 100,000 compounds per day [1] [3]. This enhanced throughput is achieved through further automation, miniaturization, and sophisticated workflow integration, allowing researchers to screen entire compound libraries comprising millions of compounds in significantly reduced timeframes [3]. The primary distinction between HTS and uHTS lies in their scale and throughput capacity, with uHTS operating at the highest end of the screening spectrum.

Table 1: Key Characteristics of HTS and uHTS

| Characteristic | HTS | uHTS |

|---|---|---|

| Throughput (compounds/day) | Thousands to hundreds of thousands | >100,000 to millions [1] [3] |

| Primary Application | Identification of active compounds ("hits") [1] | Large-scale primary screening of compound libraries [3] |

| Automation Level | Robotic systems for plate handling and processing [1] | Fully integrated, sophisticated automated workstations [3] |

| Typical Well Formats | 96, 384, 1536-well plates [1] [2] | 1536, 3456, 6144-well plates [1] |

| Liquid Handling | Automated pipetting systems | Nanolitre dispensing capabilities |

Key Methodologies and Experimental Workflows

Assay Plate Preparation and Design

The fundamental laboratory vessel for both HTS and uHTS is the microtiter plate, a disposable plastic container featuring a grid of small wells arranged in standardized formats [1]. These plates are available with 96, 192, 384, 1536, 3456, or 6144 wells, all maintaining the dimensional footprint of the original 96-well plate with 9 mm spacing [1]. The preparation process begins with compound libraries – carefully catalogued collections of stock plates that serve as the source materials for screening campaigns [1]. These libraries can be general or targeted, such as the NCATS Genesis collection (126,400 compounds), the Pharmacologically Active Chemical Toolbox (5,099 compounds), or focused libraries for specific target classes like kinases [4].

Assay plates are created through a replicating process where small liquid volumes (often nanoliters) are transferred from stock plates to empty assay plates using precision liquid handlers [1]. Each well typically contains a different chemical compound dissolved in an appropriate solvent such as dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO), though some wells may contain pure solvent or untreated samples to serve as experimental controls [1]. Proper plate design is crucial for quality control, as it helps identify and mitigate systematic errors associated with well position and enables effective data normalization [1].

Primary and Secondary Screening Protocols

The screening process follows a tiered approach to efficiently identify and validate potential drug candidates:

Primary Screening Protocol is the initial phase where large compound libraries are tested against a biological target to identify initial hits [3]. In traditional HTS, this typically involves testing each compound at a single concentration (most commonly 10 μM) [2]. The protocol involves several key steps:

- Assay Plate Preparation: Transfer test compounds from source plates to assay plates using automated liquid handling systems [1].

- Biological System Introduction: Pipette the biological entity (proteins, cells, or animal embryos) into each well [1].

- Incubation: Allow time for biological interaction under controlled environmental conditions (typically hours to days) [1].

- Signal Detection: Measure reactions using specialized detectors appropriate for the assay type (e.g., fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance) [1] [2].

- Data Acquisition: Output results as numeric values mapping to each well's activity [1].

Quantitative HTS (qHTS) represents an advanced screening approach where compounds are tested at multiple concentrations simultaneously, generating full concentration-response curves for each compound in the primary screen [5] [2]. This method uses low-volume cellular systems (e.g., <10 μl per well in 1536-well plates) with high-sensitivity detectors and provides more comprehensive data, including half-maximal effective concentration (EC₅₀), maximal response, and Hill coefficient for the entire library [5]. This approach decreases false-positive and false-negative rates compared to traditional single-concentration HTS [5] [2].

Secondary Screening Protocol involves stringent follow-up testing of initial hits to understand their mechanism of action and specificity [3]. This phase employs a "cherrypicking" approach where liquid from source wells that produced interesting results is transferred to new assay plates for further experimentation [1]. Key steps include:

- Hit Confirmation: Re-test initial hits in dose-response format to confirm activity.

- Counter-Screening: Test against related targets to assess specificity.

- Interference Testing: Evaluate compounds for assay interference (e.g., autofluorescence, compound aggregation).

- Cytotoxicity Assessment: Determine whether cellular effects are target-specific or due to general toxicity.

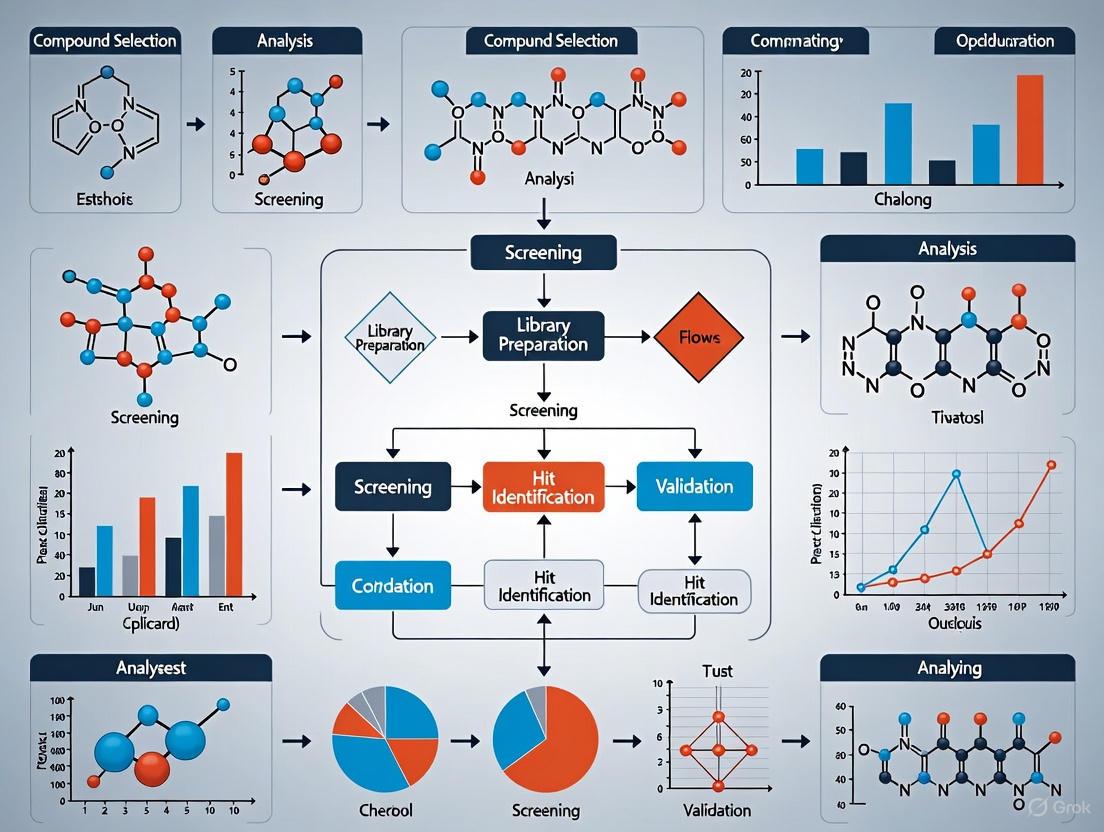

Diagram 1: HTS/uHTS Screening Workflow. This diagram illustrates the sequential process from compound library management through confirmed lead identification.

Detection Methods and Readout Technologies

HTS/uHTS platforms employ various detection methods depending on the assay design and biological system. The most common detection techniques include:

- Absorbance Spectroscopy: Measures light absorption at specific wavelengths.

- Fluorescence Intensity: Detects emission from fluorescent labels or intrinsic fluorophores.

- Fluorescence Resonance Energy Transfer (FRET): Measures energy transfer between two fluorophores to monitor molecular interactions.

- Time-Resolved Fluorescence (TRF): Uses long-lived fluorophores to reduce background interference.

- Luminescence: Detects light emission from biochemical reactions (e.g., luciferase assays).

- Bioluminescence: Measures light produced by biological organisms or reactions.

Modern HTS systems can measure dozens of plates within minutes, generating thousands of data points rapidly [1]. Ultra-high-capacity systems can analyze up to 200,000 drops per second when using microfluidic approaches [1].

Data Analysis and Quality Control

Statistical Methods for Hit Identification

The massive datasets generated by HTS/uHTS require sophisticated statistical approaches for reliable hit identification. A hit is defined as a compound with a desired size of effects in an HTS experiment, and the process of selecting these hits varies depending on the screening approach [1].

For primary screens without replicates, common analysis methods include:

- z-score method: Measures how many standard deviations a compound's response deviates from the plate mean [1].

- SSMD (Strictly Standardized Mean Difference): Assesses the size of effects and is comparable across experiments [1].

- Robust methods (z*-score, B-score, quantile-based): Less sensitive to outliers that commonly occur in HTS experiments [1].

For confirmatory screens with replicates:

- t-statistic: Suitable for screens with replicates as it directly estimates variability for each compound [1].

- SSMD with replicates: Provides a direct assessment of effect size without relying on strong distributional assumptions [1].

Table 2: Quantitative HTS Data Analysis Parameters

| Parameter | Definition | Application in Hit Selection |

|---|---|---|

| ACâ‚…â‚€ | Concentration for half-maximal response | Primary measure of compound potency; used to prioritize chemicals for further study [5] |

| Eₘâ‚â‚“ (Efficacy) | Maximal response (E∞ – Eâ‚€) | Measures maximal effect size; important for assessing allosteric effects [5] |

| Hill Coefficient (h) | Shape parameter indicating cooperativity | Provides information about steepness of concentration-response relationship [5] |

| Z-factor | Data quality assessment metric | Evaluates assay quality by measuring separation between positive and negative controls [1] |

| SSMD | Strictly Standardized Mean Difference | Assesses effect size and data quality; more robust than Z-factor for some applications [1] |

The Hill Equation in Quantitative HTS

The Hill equation (HEQN) is the most common nonlinear model used to describe qHTS concentration-response relationships [5]. The logistic form of the equation is:

Rᵢ = E₀ + (E∞ – E₀) / [1 + exp{-h[logCᵢ – logAC₅₀]}]

Where:

- Ráµ¢ = measured response at concentration Cáµ¢

- Eâ‚€ = baseline response

- E∞ = maximal response

- h = Hill slope (shape parameter)

- ACâ‚…â‚€ = concentration for half-maximal response [5]

Although the Hill equation provides convenient biological interpretations of parameters, estimates can be highly variable if the tested concentration range fails to include at least one of the two asymptotes, if responses are heteroscedastic, or if concentration spacing is suboptimal [5]. Parameter estimation improves significantly with increased sample size and appropriate concentration ranges that establish both upper and lower response asymptotes [5].

Diagram 2: Concentration-Response Curve Analysis. This diagram illustrates key parameters derived from HTS data analysis using the Hill equation.

Applications in Drug Discovery

Target Validation and Chemical Probe Development

HTS/uHTS enables systematic target validation by screening compounds with known mechanisms against novel biological targets. For example, researchers used a kinase inhibitor library to identify glycogen synthase kinase 3 (GSK3) as a negative regulator of fibroblast growth factor 21 (FGF21) in brown adipose tissue [6]. This approach confirmed GSK3's role in metabolic regulation and identified potential starting points for diabetes and obesity therapeutics [6].

In chemical biology, HTS is used to develop chemical probes – well-characterized small molecules that modulate specific protein functions – to investigate novel biological pathways and target validation [2]. These probes help establish the therapeutic potential of targets before committing to extensive drug discovery campaigns.

Drug Repurposing

Drug repurposing (repositioning) investigates new therapeutic applications for clinically approved drugs, leveraging existing safety and efficacy data to accelerate development timelines [6]. HTS of FDA-approved drug libraries has successfully identified new antiviral applications for existing drugs, such as the discovery that Saracatinib (a Src tyrosine kinase inhibitor) exhibits antiviral activity against the MERS coronavirus [6]. This approach can rapidly identify potential treatments for emerging diseases by screening existing drug collections against new biological targets.

Model and Assay Development

HTS compound libraries with known biological activities are instrumental in validating novel assay systems and disease models. Researchers developing a 3D blood-brain barrier (BBB) plus tumor model for glioma research validated their system by screening a kinase inhibitor library [6]. This approach confirmed the model's utility by demonstrating that only 9 of 27 cytotoxic compounds could penetrate the BBB to reach their targets, providing critical information about which compounds would be suitable for brain cancer applications [6].

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for HTS/uHTS

| Reagent/Library Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Kinase Inhibitor Libraries | Target-specific compound collections for kinase validation | Identification of GSK3 as regulator of FGF21 expression [6] |

| FDA-Approved Drug Libraries | Collections of clinically used compounds for repurposing | Identification of Saracatinib as MERS-CoV antiviral [6] |

| Diversity-Oriented Libraries | Structurally diverse compounds for novel target identification | NCATS Genesis collection (126,400 compounds) for broad screening [4] |

| Mechanism-Focused Libraries | Compounds targeting specific pathway classes | MIPE library (oncology-focused) for targeted screening [4] |

| Bioactive Compound Libraries | Annotated compounds with known biological effects | NPACT collection for phenotypic screening and mechanism studies [4] |

Advanced Techniques and Recent Advances

Quantitative HTS (qHTS) and High-Content Screening

Quantitative HTS (qHTS) represents a significant advancement where concentration-response curves are generated for every compound in the library simultaneously [5] [2]. This approach provides more reliable potency (ACâ‚…â‚€) and efficacy (Eₘâ‚â‚“) measurements, enabling immediate structure-activity relationship (SAR) analysis without follow-up testing [5]. The National Institutes of Health Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC) developed this paradigm to pharmacologically profile large chemical libraries through full concentration-response relationships [1].

High-Content Screening (HCS) extends HTS by incorporating automated microscopy and image analysis to capture multiple parameters at the cellular or subcellular level. This approach provides rich phenotypic information beyond simple activity measurements, enabling researchers to understand compound effects on complex cellular processes.

Miniaturization and Microfluidic Technologies

Recent technological advances have dramatically increased screening throughput while reducing costs. Microfluidic approaches using drop-based technology have demonstrated the ability to perform 100 million reactions in 10 hours at approximately one-millionth the cost of conventional techniques [1]. These systems replace traditional microplate wells with picoliter-to-nanoliter droplets separated by oil, allowing analysis and hit sorting while reagents flow through microchannels [1].

Further innovations include silicon sheets of lenses that can be placed over microfluidic arrays to simultaneously measure 64 different output channels with a single camera, enabling analysis of 200,000 drops per second [1]. These advances continue to push the boundaries of screening throughput while reducing reagent consumption and costs.

Specialized Screening Applications

HTS/uHTS technologies have expanded beyond traditional drug discovery to include:

- Toxicology Screening (Tox21 program): Testing over 10,000 chemicals across multiple concentrations for hazard assessment [5].

- Chemical Biology: Identifying chemical probes to explore biological pathways and target validation [2].

- ADMET/DMPK Profiling: Frontloading absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, toxicity, and drug metabolism/pharmacokinetics studies earlier in the discovery process [2].

These applications demonstrate the versatility of HTS/uHTS platforms in addressing diverse research questions beyond initial hit identification in drug discovery.

The Role of Compound Libraries as the Cornerstone of Hit Identification

In modern drug discovery, the identification of initial hit compounds is a critical first step in the long journey toward new therapeutics. Compound libraries form the essential foundation for this process, providing the diverse chemical matter from which potential drugs can be discovered. The strategic design, curation, and application of these libraries directly influence the success rate of hit identification campaigns. This application note examines the composition, management, and implementation of compound libraries within high-throughput screening (HTS) paradigms, providing researchers with practical frameworks for leveraging these resources effectively. We detail specific protocols and quantitative metrics to guide the selection and deployment of compound libraries across various screening methodologies, with the aim of optimizing hit identification outcomes.

Compound Library Composition and Characteristics

A well-curated compound library is characterized by its diversity, quality, and drug-like properties. Leading screening facilities maintain extensive collections ranging from 411,200 to over 850,000 compounds, selected for structural diversity and biological relevance [7] [8]. These libraries are meticulously designed to increase the probability of identifying genuine hits while minimizing false positives through the exclusion of problematic chemical structures [9].

Library Diversity and Design Strategies

- Structural Diversity: The KU-HTS laboratory reports that their collection of approximately 411,200 compounds contains more than 61,980 unique scaffolds, ensuring broad coverage of chemical space [8].

- Drug-Like Properties: Modern screening collections are filtered according to Lipinski's Rule of Five and exhibit favorable ADME (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion) profiles to improve the likelihood of downstream development success [9] [8].

- Specialized Sublibraries: Comprehensive screening libraries typically contain specialized subsets for targeted approaches:

Table 1: Characteristics of Representative Compound Libraries

| Library Source | Total Compounds | Key Features | Specialized Sublibraries |

|---|---|---|---|

| Evotec | >850,000 | Quality, diversity, novelty; drug-like properties | 25,000 fragments; 30,000 natural products; 2,000 macrocycles [7] |

| KU-HTS Laboratory | ~411,200 | >61,980 unique scaffolds; Lipinski's Rule of Five compliance | 16,079 bioactives and FDA-approved compounds; 12,805 natural products [8] |

| Maybridge | 51,000+ | Structurally diverse; heterocyclic chemistry focus; high drug-likeness | Focused libraries for antivirals, antibacterials, PPIs, GPCRs, kinases [9] |

Compound Library Formats and Supply

Screening compounds are available in various formats to accommodate different screening platforms and workflows. The Maybridge library, for example, offers compounds in pre-plated formats including 96-well plates with 1 μmol dry film and 384-well microplates with 0.25 μmol dry film [9]. Most major brands of plates and vials are supported, facilitating integration with existing automation systems. Approximately 95% of compounds in well-maintained collections are available in >5 mg quantities, with over 90% available in >50 mg quantities for follow-up studies [9].

Hit Identification Methodologies and Protocols

Hit identification technologies have evolved beyond traditional HTS to include multiple complementary approaches. The selection of an appropriate methodology depends on target biology, available resources, and desired hit characteristics.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS)

HTS involves the rapid testing of large compound libraries against biological targets using automated systems. A typical HTS campaign follows a structured workflow from assay development to hit confirmation.

Table 2: Comparison of Hit Identification Technologies

| Technology | Typical Library Size | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional HTS | 100,000 - 1,000,000+ | Well-established; direct activity readout; extensive infrastructure | High cost; significant infrastructure requirements [7] |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DEL) | Billions (e.g., 150 billion) | Extremely large library size; efficient affinity selection | DNA-incompatible chemistry; unsuitable for nucleic acid-binding targets [10] [7] |

| Fragment-Based Screening | 1,000 - 25,000 | Efficient coverage of chemical space; high ligand efficiency | Requires sensitive biophysical detection methods [7] |

| Affinity Selection MS | 10,000 - 750,000 | Label-free; direct binding measurement; suitable for complex targets | Complex data analysis; specialized expertise required [10] |

Protocol 3.1.1: HTS Campaign Implementation

Assay Development and Optimization

- Develop a robust assay with appropriate sensitivity and specificity for the target

- Miniaturize assay to 384-well or 1536-well format to reduce reagent costs and increase throughput

- Optimize assay conditions (buffer, pH, temperature, incubation times) for maximum reproducibility

- Implement appropriate controls (positive, negative, vehicle) to monitor assay performance

Primary Screening

- Screen compound library at single concentration (typically 1-10 μM) in duplicate or triplicate

- Use automation systems for liquid handling and plate processing to ensure consistency

- Include quality control metrics (Z'-factor > 0.5) to validate screen performance [7]

Hit Confirmation

- Retest primary hits in concentration-response format to determine IC50/EC50 values

- Conduct orthogonal assays using different technology platforms to confirm activity

- Perform counter-screens to identify assay interference compounds (e.g., fluorescence quenchers, aggregators) [7]

Emerging Technologies: Barcode-Free Self-Encoded Libraries

Recent advances have enabled the development of barcode-free self-encoded libraries (SELs) that combine solid-phase combinatorial synthesis with tandem mass spectrometry for hit identification. This approach screens libraries of 104 to 106 compounds in a single experiment without DNA barcoding [10].

Protocol 3.2.1: Self-Encoded Library Screening

Library Synthesis

- Perform solid-phase split-and-pool synthesis using diverse chemical scaffolds (e.g., amino acid backbones, benzimidazole cores, Suzuki coupling products)

- Employ drug-like building blocks filtered by Lipinski parameters (MW, logP, HBD, HBA, TPSA) [10]

- Validate synthetic steps for efficiency (>65% conversion) to ensure library quality

Affinity Selection

- Incubate the library with immobilized target protein under physiological conditions

- Separate bound from unbound compounds through washing steps

- Elute specifically bound compounds for analysis

Hit Deconvolution by Tandem Mass Spectrometry

- Analyze eluted compounds using nanoLC-MS/MS

- Annotate structures using software tools (SIRIUS, CSI:FingerID) for reference spectra-free identification [10]

- Decode hits based on MS/MS fragmentation patterns against the enumerated library

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful hit identification campaigns require careful selection of reagents, tools, and platforms. The following table details essential components for compound library screening.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Hit Identification

| Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening Compound Libraries | Maybridge HitFinder; ChemBridge DIVERSet; ChemDiv Diversity; Life Chemicals 3DShape [9] [8] | Source of chemical diversity for hit identification | Structurally diverse; drug-like properties; excluded problematic functional groups |

| Cheminformatics Platforms | RDKit; ChemAxon Suite; CFM-ID; MSFinder [11] [12] | Virtual screening; compound management; SAR analysis; MS/MS annotation | Molecular fingerprinting; descriptor calculation; fragmentation prediction |

| Mass Spectrometry Tools | mzCloud; SIRIUS; CSI:FingerID [10] [11] | Compound identification; structure annotation; hit deconvolution | Spectral libraries; in silico fragmentation prediction; database searching |

| Specialized Compound Sets | FDA-approved drug libraries; Natural product collections; Fragment libraries; Covalent inhibitors [7] [8] | Targeted screening approaches; drug repurposing; exploring specific chemical space | Known bioactivity; clinical safety data; specific molecular properties |

| FAAH/MAGL-IN-3 | FAAH/MAGL-IN-3, MF:C15H13NOS, MW:255.3 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

| Variculanol | Variculanol, MF:C25H40O2, MW:372.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent | Bench Chemicals |

Hit Validation and Confirmation Protocols

Initial screening hits require rigorous validation to distinguish genuine actives from false positives. A multi-tiered approach is essential for hit confirmation.

Protocol 5.1: Hit Triage and Validation

Confirmatory Screening

- Retest initial hits in the primary assay format using freshly prepared compound solutions

- Establish concentration-response relationships (IC50, EC50, Ki) to quantify potency

- Assess intra-assay and inter-assay reproducibility

Orthogonal Assays

- Implement secondary assays using different detection technologies (e.g., SPR, ITC, thermal shift) to confirm target engagement [7]

- For enzyme targets, use different substrate analogs or assay formats to verify mechanism of action

- For cellular assays, confirm activity in relevant disease models

Counter-Screening and Selectivity Profiling

- Test compounds against related targets to establish preliminary selectivity profiles

- Screen for assay interference mechanisms (e.g., fluorescence, luciferase inhibition, aggregation) [7]

- Evaluate cytotoxicity in relevant cell lines to identify non-specific effects

Early ADMET Assessment

- Determine physicochemical properties (solubility, stability, logD)

- Assess metabolic stability in liver microsomes

- Evaluate membrane permeability (e.g., Caco-2, PAMPA)

Compound libraries serve as the fundamental resource for hit identification in drug discovery, with their composition and quality directly influencing screening outcomes. This application note has detailed the strategic composition of screening libraries, practical protocols for their implementation in various screening paradigms, and essential methodologies for hit validation. As screening technologies continue to evolve—with innovations such as barcode-free self-encoded libraries and advanced computational annotation methods—the strategic design and application of compound libraries will remain paramount to successful hit identification. Researchers are encouraged to select screening approaches based on their specific target biology, available resources, and desired hit characteristics, while implementing rigorous hit confirmation protocols to ensure the identification of chemically tractable starting points for medicinal chemistry optimization.

High-throughput screening (HTS) represents a foundational pillar of modern drug discovery and biomedical research, serving as a practical method to query large compound collections in search of novel starting points for biologically active compounds [13]. The efficacy of HTS campaigns is intrinsically linked to the quality, diversity, and strategic composition of the compound libraries screened. Over decades, library technologies have evolved from simple collections of natural products and synthetic dyes to sophisticated arrays of millions of synthetically accessible compounds and encoded combinatorial libraries [13].

This application note details the major types of compound libraries utilized in contemporary screening paradigms: diverse, focused, DNA-encoded, and combinatorial libraries. We provide a structured comparison of their characteristics, detailed experimental protocols for their application, and visualization of key workflows. The content is framed within the context of a broader thesis on high-throughput screening methods, aiming to equip researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with the practical knowledge to select and implement the most appropriate library strategy for their specific discovery goals.

Library Types and Quantitative Comparisons

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Major Compound Library Types

| Library Type | Core Purpose | Typical Size Range | Key Characteristics | Example Composition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diverse Screening Collections [14] [8] | Identify novel hits across diverse biological targets. | 100,000 - 500,000 compounds | "Drug-like" properties (Lipinski's Rule of Five); filtered for reactive/undesirable groups; structural diversity. | ChemDiv (50K), SPECS (30K), ChemBridge (23.5K) [14]; Vendor collections from ChemBridge, ChemDiv, Life Chemicals [8]. |

| Focused/Targeted Libraries [14] [4] | Interrogate specific target classes or pathways. | 200 - 50,000 compounds | Compounds annotated for specific mechanisms (e.g., kinases, epigenetics); includes FDA-approved drugs for repurposing. | Kinase-targeted (10K), CNS-penetrant (47K), FDA-approved drugs (2,500-3,000) [14] [4]. |

| DNA-Encoded Libraries (DELs) [15] [16] | Affinity-based screening of ultra-large libraries. | Millions to Billions of compounds | Combinatorial synthesis with DNA barcoding; screened as a mixture; hit identification via DNA sequencing. | Triazine-based libraries; synthesized via "split and pool" with DNA ligation [15]. |

| Combinatorial (Make-on-Demand) [17] [10] | Access vast, synthetically accessible chemical space in silico and in vitro. | Billions of compounds | Built from lists of substrates and robust reactions; screened virtually or via affinity selection. | Enamine REAL Space (20B+ molecules) [17]; Barcode-free Self-Encoded Libraries (SELs) [10]. |

Table 2: Exemplary Library Compositions from Major Screening Centers

| Screening Center | Collection Name | Number of Compounds | Description & Strategic Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stanford HTS @ The Nucleus [14] | Diverse Screening Collection | ~127,500 | The major diversity-based library, filtered for drug-like properties and the absence of reactive functionalities. |

| Known Bioactives & FDA-Approved Drugs | ~11,300 | Used for assay validation, smaller screens, and drug repurposing. Includes LOPAC1280, Selleckchem FDA library, etc. | |

| Compound Fragment Libraries | ~5,000 | For Fragment-Based Drug Discovery (FBDD), screened using Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR). | |

| NCATS [4] | Genesis | 126,400 | A novel modern chemical library emphasizing high-quality chemical starting points and core scaffolds for derivatization. |

| NCATS Pharmaceutical Collection (NPC) | ~2,800 | Contains all compounds approved by the U.S. FDA, ideal for drug repurposing campaigns. | |

| Mechanism Interrogation PlatEs (MIPE) | ~2,800 | An oncology-focused library with equal representation of approved, investigational, and preclinical compounds. | |

| KU High-Throughput Screening Lab [8] | Total Compound Collection | ~411,200 | A carefully selected collection from commercial vendors, optimized for structural diversity and drug-like properties. |

| Bioactives and FDA-Approved Compounds | ~16,100 | Annotated set for drug repurposing, known to impact diverse signaling pathways. | |

| Natural Products | ~12,800 | Purified natural products from various suppliers, with non-drug-like compounds (e.g., peptides, fatty acids) discarded. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Virtual High-Throughput Screening (vHTS) of Ultra-Large Make-on-Demand Libraries

This protocol describes the use of the REvoLd evolutionary algorithm for screening billion-member combinatorial libraries in Rosetta, accounting for full ligand and receptor flexibility [17].

1. Library and Preprocessing: - Library Selection: Obtain the list of substrates and reaction rules for a make-on-demand library (e.g., Enamine REAL Space). - Target Preparation: Prepare the protein target structure in a format compatible with RosettaLigand. This includes adding hydrogen atoms, assigning partial charges, and defining the binding site.

2. REvoLd Docking Run: - Initialization: Generate a random start population of 200 ligands from the combinatorial chemical space. - Evolutionary Optimization: Run the algorithm for 30 generations. In each generation: - Docking & Scoring: Dock all individuals in the current population using the RosettaLigand flexible docking protocol. - Selection: Select the top 50 scoring individuals ("the fittest") to advance. - Reproduction: Apply crossover (recombining parts of fit molecules) and mutation (switching fragments for alternatives) steps to the selected population to create the next generation of ligands. - Output: The algorithm returns a list of top-scoring molecules discovered during the run. Multiple independent runs are recommended to explore diverse scaffolds.

3. Hit Analysis and Triage: - Analyze the predicted binding poses and scores of the top-ranking compounds. - Cross-reference the selected compounds with the make-on-demand vendor catalog for commercial availability and synthesis feasibility. - Select a subset of diverse, high-ranking compounds for purchase and experimental validation.

Protocol 2: Affinity Selection and Analysis of a DNA-Encoded Library (DEL)

This protocol outlines the key steps for performing an affinity selection with a DEL and analyzing the resulting sequencing data using a robust normalized z-score metric [15].

1. Affinity Selection: - Incubation: Incubate the pooled DEL (containing billions of members) with an epitope-tagged protein target immobilized on beads. - Washing: Remove unbound library members through a series of buffer washes. The stringency of washing can be adjusted to probe binding affinity. - Elution: Elute the protein-bound molecules, typically by denaturing the protein or using a competitive ligand. - DNA Recovery and Amplification: Isolate the DNA barcodes from the eluted compounds and amplify them via PCR for next-generation sequencing.

2. Sequencing and Data Decoding: - Sequence the amplified DNA barcodes using a next-generation sequencing platform. - Decode the DNA sequences into their corresponding chemical structures based on the library's encoding scheme.

3. Enrichment Analysis using Normalized Z-score:

- For each unique library member (or conserved substructure, i.e., n-synthon), calculate its enrichment using the normalized z-score metric, which is robust to library diversity and sequencing depth [15].

- Equation: Normalized Z = (p_o - p_e) / sqrt(p_e * (1 - p_e)) * sqrt(C_o), where p_o is the observed frequency, p_e is the expected frequency (e.g., from a non-target control selection), and C_o is the total number of observed counts in the selection.

- Visualization: Plot the results in a 2D or 3D scatter plot ("cubic view"), where each point represents a unique compound or n-synthon, colored or sized by its normalized z-score. Look for lines or planes of high-scoring points, indicating conserved, enriched chemical substructures.

4. Hit Identification: - Prioritize compounds belonging to significantly enriched n-synthons for resynthesis and off-DNA validation in secondary assays.

Protocol 3: High-Throughput Phenotypic Screening with Focused Libraries

This protocol is based on a recent screen for anthelmintic drugs, demonstrating the use of focused libraries in a phenotypic assay [18] [19].

1. Assay Development and Validation: - Model System: Establish a robust phenotypic assay. Example: Use the nematode C. elegans as a surrogate for parasitic helminths in a motility inhibition assay [19]. - Validation: Validate the assay using known positive and negative controls. Calculate a Z' factor > 0.5 to confirm assay robustness and suitability for HTS.

2. Primary Single-Concentration Screen: - Library Plating: Dispense compounds from focused libraries (e.g., FDA-approved drugs, natural products) into 384-well assay plates. - Screening: Treat the model organism with each compound at a single concentration (e.g., 110 µM). Measure the phenotypic endpoint (e.g., motility) at relevant time points (e.g., 0h and 24h). - Hit Selection: Define a hit threshold (e.g., >70% motility inhibition). Identify "pre-hits" meeting this criterion.

3. Dose-Response Confirmation: - Re-test the pre-hits in a dose-response format to determine their half-maximal effective concentration (EC50). - Criteria for Progression: Select compounds with acceptable potency (e.g., EC50 < 20 µM) and a dose-response curve with R > 0.90 and p-value < 0.05.

4. Counter-Screening and Selectivity Assessment: - Test the confirmed hits for toxicity against relevant host cell models, such as HepG2 liver spheroids or mouse intestinal organoids [19]. - Calculate a selective index (SI) to prioritize compounds with a favorable efficacy-toxicity profile.

Workflow Visualization

DEL Screening and Analysis

REvoLd Evolutionary Screening

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Compound Library Screening

| Item | Function/Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Lipinski's Rule of Five Filter [14] [13] | Computational filter to prioritize compounds with "drug-like" properties (MW ≤ 500, AlogP ≤ 5, HBD ≤ 5, HBA ≤ 10). | Curating diverse screening collections to increase the likelihood of oral bioavailability. |

| REOS Filter [14] [13] | Rapid Elimination Of Swill; removes compounds with reactive or undesired functional groups to reduce HTS artifacts. | Filtering vendor libraries to eliminate pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) and other promiscuous binders. |

| Normalized Z-Score Metric [15] | A robust statistical metric for analyzing DEL selection data, insensitive to library diversity and sequencing depth. | Quantifying the enrichment of specific compounds or n-synthons from DEL selections against a protein target. |

| RosettaLigand & REvoLd [17] | Software suite for flexible protein-ligand docking and an evolutionary algorithm for searching ultra-large combinatorial libraries. | Performing structure-based virtual screens of billion-member make-on-demand libraries like Enamine REAL. |

| Barcode-Free SEL Platform [10] | Affinity selection platform using tandem MS and automated structure annotation to screen massive libraries without DNA tags. | Screening targets incompatible with DELs, such as DNA-binding proteins (e.g., FEN1). |

| 3D Cell Models (Spheroids/Organoids) [19] | Advanced in vitro models for more physiologically relevant toxicity and efficacy assessment. | Counter-screening primary hits from phenotypic campaigns to determine selective index and prioritize safer leads. |

| 14-Anhydrodigitoxigenin | 3beta-Hydroxy-5beta-carda-14,20(22)-dienolide|Cardenolide RUO | High-purity 3beta-Hydroxy-5beta-carda-14,20(22)-dienolide for research use only (RUO). Explore its application in natural product and pharmacology studies. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Enpp-1-IN-2 | Enpp-1-IN-2, MF:C15H18N6, MW:282.34 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a fundamental paradigm shift in modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid evaluation of hundreds of thousands of chemical compounds against biological targets. This approach leverages specialized automation, robotics, and miniaturized assay formats to quickly and economically identify potential drug candidates [20] [21]. The operational change from conventional single-sample methods to massive parallel experimentation has become essential for target validation and compound library exploration in pharmaceutical research and academic institutions [21] [22]. The successful implementation of HTS infrastructure requires maximal efficiency and miniaturization, with the ability to accommodate diverse assay formats and screening protocols while generating robust, reproducible data sets under standardized conditions [21] [22].

The core infrastructure of any HTS facility rests upon three essential pillars: sophisticated robotic systems for unattended operation, microplate formats that enable miniaturization and reagent conservation, and diverse compound libraries that provide the chemical matter for discovery. Together, these components create an integrated ecosystem that dramatically increases the number of samples processed per unit time while reducing operational variability compared to manual processing [21]. This technological foundation has evolved significantly, with current generation screening instrumentation becoming so robust and application-diverse that HTS is now utilized to investigate entirely new areas of biology and chemistry beyond traditional pharmaceutical applications [22].

Robotic Platforms for High-Throughput Screening

System Architecture and Core Components

Robotic platforms provide the precise, repetitive, and continuous movement required to realize the full potential of HTS workflows. At the heart of an HTS platform is the integration of diverse instrumentation through sophisticated robotics that move microplates between functional modules without human intervention [21]. These systems typically employ Cartesian and articulated robotic arms for plate movement alongside dedicated liquid handling systems that manage complex pipetting routines. A representative example of a fully integrated system can be found at the National Institutes of Health's Chemical Genomics Center (NCGC), which utilizes a robotic screening system capable of storing compound collections, performing assay steps, and measuring various assay outputs in a fully integrated manner [22].

The NCGC system incorporates three high-precision Stäubli robotic arms to execute hands-free biochemical and cell-based screening protocols, with peripheral units including assay and compound plate carousels, liquid dispensers, plate centrifuges, and plate readers [22]. This configuration provides a total capacity of 2,565 plates, with 1,458 positions dedicated to compound storage and the remaining 1,107 positions dedicated to assay plate storage, enabling random access to any individual plate at any given time [22]. Such comprehensive automation allows for continuous 24/7 operation, dramatically improving the utilization rate of expensive analytical equipment and enabling the screening of over 2.2 million compound samples representing approximately 300,000 compounds prepared as a seven-point concentration series [22].

Key Robotic Modules and Functions

Integrated HTS systems combine several specialized modules that perform specific functions within the screening workflow. Each module serves a distinct purpose in the automated pipeline, with precise coordination managed by integration software or a scheduler that acts as the central orchestrator [21]. The table below summarizes the primary robotic modules and their essential functions in a typical HTS platform:

Table 1: Key Robotic Modules in HTS Platforms

| Module Type | Primary Function | Key Features and Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handler | Precise fluid dispensing and aspiration | Sub-microliter accuracy; low dead volume; multiple independent pipetting heads [21] |

| Plate Incubator | Temperature and atmospheric control | Uniform heating across microplates; control of COâ‚‚ and humidity; rotating carousel design [22] |

| Microplate Reader | Signal detection | Multiple detection modes (fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance); high sensitivity; rapid data acquisition [21] |

| Plate Washer | Automated washing cycles | Minimal residual volume; effective cross-contamination control [21] |

| Microplate Handler | Plate transfer and positioning | Submillimeter accuracy; barcode scanning; compatibility with multiple plate formats [23] |

| Compound Storage | On-line library storage | Random access; temperature control; capacity for thousands of plates [22] |

Modern microplate handlers have evolved into sophisticated integration hubs that bridge communication between instruments from different manufacturers. These systems maintain tight control over handling parameters by consistently positioning plates with submillimeter accuracy, applying uniform pressure on instruments, and regulating movement speeds to minimize splashing or cross-contamination [23]. Advanced sensors verify plate placement and detect anomalies before impacting results, while integrated barcode scanning provides seamless sample tracking and establishes a digital chain of custody to support regulatory compliance [23].

Microplate Formats and Assay Miniaturization

Standard Microplate Formats and Applications

Microplate selection represents a critical consideration in HTS infrastructure, directly impacting reagent consumption, throughput capacity, and data quality. The evolution from 96-well to higher density formats has been instrumental in increasing screening efficiency while reducing costs. Modern HTS predominantly utilizes 384-well and 1536-well plates, with each format offering distinct advantages and challenges for different screening scenarios [21] [22]. The choice of format depends on multiple factors including assay type, reagent availability, detection sensitivity, and available instrumentation.

The implementation of 1536-well plate formats as a standard has been particularly important for large-scale screening operations, enabling maximal efficiency and miniaturization while accommodating the testing of extensive compound libraries [22]. This extreme miniaturization demands extreme precision in fluid handling, which manual pipetting cannot reliably deliver across thousands of replicates [21]. The progression to higher density formats has been facilitated by continuous advances in liquid dispensing technologies capable of handling sub-microliter volumes with the precision required for robust assay performance.

Table 2: Standard Microplate Formats in HTS

| Format | Well Volume | Typical Assay Volume | Throughput Advantage | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 96-well | 300-400 µL | 50-200 µL | Baseline | Pilot studies, assay development, specialized assays [24] |

| 384-well | 50-100 µL | 10-50 µL | 4x compared to 96-well | Primary screening, cell-based assays [21] [24] |

| 1536-well | 5-10 µL | 2-5 µL | 16x compared to 96-well | Large compound library screening, quantitative HTS [22] |

Miniaturization Benefits and Technical Considerations

The miniaturization enabled by high-density microplates provides significant benefits for HTS operations. Reduced assay volumes directly conserve expensive reagents and proprietary compounds, particularly important when working with rare biological materials or valuable chemical libraries [21]. This miniaturization also increases throughput by allowing more tests to be performed in the same footprint, with 1536-well plates enabling the screening of hundreds of thousands of compounds in days rather than weeks or months [24].

However, successful implementation of high-density formats requires careful attention to several technical considerations. Evaporation effects become more significant with smaller volumes, potentially necessitating environmental controls or specialized lids. Liquid handling precision must increase correspondingly with decreasing volumes, as measurement errors that might be negligible in 96-well formats can become substantial in 1536-well plates [21]. Additionally, detection systems must provide sufficient sensitivity to measure signals from minute quantities of biological material or chemical compounds while maintaining the speed necessary to process thousands of wells in a reasonable timeframe.

Compound Library Management

Library Composition and Diversity

Compound libraries form the foundational chemical matter for HTS campaigns, with library quality and diversity directly impacting screening success rates. A typical academic HTS facility, such as the Stanford HTS @ The Nucleus, maintains a collection of over 225,000 diverse compounds organized into specialized sub-libraries tailored for different screening objectives [14]. These libraries are strategically assembled to balance chemical diversity with drug-like properties, employing rigorous computational filters to eliminate compounds with undesirable characteristics while ensuring broad coverage of chemical space.

The composition of a representative academic screening collection demonstrates the strategic approach to library design. The Stanford library includes a Diverse Screening Collection of approximately 127,500 drug-like molecules sourced from multiple commercial providers (ChemDiv, SPECS, Chembridge, ChemRoutes) to ensure structural variety [14]. This foundation is supplemented with targeted libraries for specific applications, including an Enamine-CNS Library of 47,360 molecules selected for blood-brain barrier penetration, kinase-focused libraries (ChemDiv Kinase 10K, ChemDiv Allosteric Kinase Inhibitor Library 26K), and specialized collections for pathways such as Sag/Hedgehog (3,300 compounds) [14]. Additionally, focused covalent libraries totaling over 21,000 compounds targeting cysteine, lysine, and serine residues provide chemical tools for investigating covalent inhibition strategies [14].

Specialized Libraries for Screening Applications

Beyond general diversity collections, specialized compound libraries serve distinct purposes in the drug discovery pipeline. Known bioactives and FDA-approved drugs (totaling 11,272 compounds in the Stanford collection) play a crucial role in assay validation, smaller screens, and drug repurposing efforts [14]. These libraries include well-characterized compounds such as the Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds (LOPAC1280), NIH Clinical Collection (NIHCC), Microsource Spectrum, and various FDA-approved drug libraries from commercial providers [14]. The use of such libraries for drug repurposing was demonstrated in a recent unbiased HTS of drug-repurposing libraries that identified small-molecule inhibitors of clot retraction, highlighting the value of screening compounds with established safety profiles [25].

Fragment libraries represent another specialized resource for early discovery, with the Stanford facility maintaining a 5,000-compound fragment collection for surface plasmon resonance screening [14]. These libraries typically contain smaller molecules (molecular weight <300) with simplified structures, enabling coverage of a broader chemical space with fewer compounds and identifying weak binders that can be optimized into potent leads.

Table 3: Compound Library Types and Applications

| Library Type | Size Range | Composition | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diverse Screening Collection | 100,000+ compounds | Drug-like molecules from multiple sources | Primary screening for novel hits [14] |

| Targeted Libraries | 3,000-50,000 compounds | Compounds selected for specific target classes | Focused screening for gene families [14] |

| Known Bioactives & FDA Drugs | 5,000-15,000 compounds | Approved drugs and well-characterized bioactives | Assay validation, drug repurposing [14] [25] |

| Fragment Libraries | 1,000-5,000 compounds | Low molecular weight compounds (<300 Da) | Fragment-based screening [14] |

| Covalent Libraries | 5,000-25,000 compounds | Compounds with electrophilic warheads | Covalent inhibitor discovery [14] |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS) Protocol

Quantitative High-Throughput Screening (qHTS) has emerged as a powerful paradigm that tests each library compound at multiple concentrations to construct concentration-response curves (CRCs) during the primary screen, generating a comprehensive data set for each assay [22]. This approach mitigates the well-known high false-positive and false-negative rates of conventional single-concentration screening by providing immediate information on compound potency and efficacy [22]. The practical implementation of qHTS for cell-based and biochemical assays across libraries of >100,000 compounds requires sophisticated automation and miniaturization to manage the substantial increase in screening throughput.

The qHTS workflow begins with assay validation and optimization using control compounds to establish robust assay performance metrics. The library compounds are prepared as dilution series in 1536-well plates, typically spanning seven or more concentrations across an approximately four-log range [22]. This multi-concentration format significantly enhances the reliability of activity assessment, as complex biological responses are readily apparent from the curve shape and automatically recorded [22]. The NCGC experience demonstrates that this paradigm shift from single-point to concentration-response screening, while requiring more initial screening throughput, ultimately increases efficiency by moving the burden of reliable chemical activity identification from labor-intensive post-HTS confirmatory assays to automated primary HTS [22].

Diagram 1: qHTS screening workflow

HTS Assay Validation and Quality Control

Robust assay validation is a prerequisite for successful HTS campaigns, ensuring that screening data is reliable and reproducible. Key performance metrics must be established before initiating full-library screening to minimize false positives and negatives. The Z'-factor has emerged as the gold standard for assessing assay quality, with values between 0.5 and 1.0 indicating excellent assay robustness [21] [24]. This statistic assesses assay robustness by comparing the signal separation between positive and negative control populations, providing a quantitative measure of assay suitability for HTS [21].

Additional quality metrics include signal-to-background ratio, coefficient of variation (CV) for controls, and dynamic range to distinguish active from inactive compounds [24]. These parameters should be monitored throughout the screening campaign to detect any drift in assay performance. Modern automated systems incorporate real-time quality control measures, calculating and reporting these metrics during screening operations to ensure maintained data quality [21]. Implementation of appropriate controls is essential, with most HTS assays including positive controls (known activators or inhibitors), negative controls (vehicle-only treatments), and often reference compounds to monitor assay stability throughout the screening process.

Diagram 2: HTS assay validation workflow

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of HTS relies on a comprehensive ecosystem of research reagents and materials specifically designed for automated screening environments. These solutions encompass detection technologies, specialized assay kits, and supporting reagents that ensure robust performance in miniaturized formats. The selection of appropriate reagent systems is critical for maintaining assay quality throughout extended screening campaigns.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTS

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Universal Detection Technologies | Transcreener ADP² Assay | Homogeneous, mix-and-read assays for multiple target classes (kinases, GTPases, ATPases) using FP, FI, or TR-FRET detection [24] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Reporter gene assays, viability assays, second messenger signaling | Phenotypic screening and pathway analysis in live cells [24] |

| Specialized Chemical Libraries | Library of Pharmacologically Active Compounds (LOPAC), NIH Clinical Collection | Assay validation and control compounds [14] |

| Covalent Screening Libraries | Cysteine-focused, lysine covalent, serine hydrolase libraries | Targeted screening for covalent inhibitors [14] |

| Automation-Compatible Substrates | Luminescent, fluorescent, and absorbance substrates | Detection of enzyme activity in automated formats [24] |

| Cell Culture Reagents | Specialized media, reduced-serum formulations | Automated cell culture maintenance and assay readiness [23] |

Universal detection technologies such as BellBrook Labs' Transcreener platform exemplify the trend toward flexible assay systems that can be applied across multiple target classes. These platforms deliver sensitive detection for diverse enzymes including kinases, ATPases, GTPases, helicases, PARPs, sirtuins, and cGAS using fluorescence polarization (FP), fluorescence intensity (FI), or time-resolved FRET (TR-FRET) formats [24]. This versatility enables standardization of detection methods across multiple screening campaigns, reducing development time and improving data consistency. The availability of such robust, interference-resistant detection systems has been particularly valuable for challenging target classes where traditional assay approaches may suffer from compound interference or limited dynamic range.

The infrastructure supporting modern High-Throughput Screening represents a sophisticated integration of robotics, miniaturization technologies, and compound management systems that collectively enable the efficient evaluation of chemical libraries against biological targets. Robotic platforms with precise liquid handling capabilities, multi-mode detection systems, and automated plate management form the physical foundation of HTS operations [21] [22]. These systems are complemented by standardized microplate formats that enable assay miniaturization and reagent conservation while maintaining data quality [21] [22]. The chemical libraries screened in these systems have evolved from simple diversity collections to sophisticated sets including targeted libraries, known bioactives, and specialized compounds for specific screening applications [14].

The implementation of quantitative HTS approaches has transformed screening from a simple active/inactive classification to a rich data generation process that provides immediate information on compound potency and efficacy [22]. This paradigm shift, combined with robust assay validation methodologies and universal detection technologies, has significantly increased the success rates of HTS campaigns across diverse target classes [24]. As HTS continues to evolve, emerging trends including artificial intelligence for screening design and analysis, 3D cell culture systems for more physiologically relevant assays, and even higher density microplate formats promise to further enhance the efficiency and predictive power of this essential drug discovery technology [24] [23].

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) represents a foundational approach in modern drug discovery, enabling the rapid experimental testing of hundreds of thousands of chemical compounds against biological targets to identify promising therapeutic candidates [1]. This automated method leverages robotics, sophisticated data processing software, liquid handling devices, and sensitive detectors to conduct millions of chemical, genetic, or pharmacological tests in remarkably short timeframes [1]. The results generated from HTS campaigns provide crucial starting points for drug design and for understanding the interaction between chemical compounds and specific biomolecular pathways. The fundamental goal of HTS is to identify "hit" compounds – those with confirmed desirable activity against the target – which can then be further optimized in subsequent drug development phases [1].

The critical path of HTS follows a structured workflow that begins with the careful preparation and curation of compound libraries, proceeds through automated screening processes, and culminates in rigorous hit confirmation procedures. This comprehensive pathway integrates multiple scientific disciplines, including chemistry, biology, engineering, and bioinformatics, to efficiently transform vast chemical collections into validated starting points for therapeutic development. As the demand for novel therapeutics continues to grow, particularly for complex diseases with unmet medical needs, HTS remains an indispensable technology for accelerating early-stage drug discovery across academic institutions, pharmaceutical companies, and biotechnology firms [26].

Compound Library Preparation

The foundation of any successful HTS campaign lies in the quality and diversity of the compound library screened. These carefully curated collections represent the chemical starting points from which potential therapeutics may emerge. A typical screening library contains hundreds of thousands of diverse compounds, with comprehensive HTS facilities often maintaining collections exceeding 225,000 distinct molecules [14]. These libraries are not monolithic; rather, they comprise strategically selected sub-libraries designed to probe different aspects of chemical space and biological relevance.

Table 1: Representative Composition of a Diverse HTS Compound Library

| Library Type | Number of Compounds | Primary Characteristics | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diverse Screening Collection | ~127,500 | Drug-like molecules, Lipinski's "Rule of 5" compliance | Primary screening for novel hit identification |

| Target-Class Libraries | ~36,300 | Focused on specific target classes (e.g., kinases) | Screening against target families with known structural motifs |

| Covalent Libraries | ~21,120 | Reactive functional groups (cysteine-focused, lysine-focused) | Targets with nucleophilic residues amenable to covalent modification |

| Known Bioactives & FDA Drugs | ~11,272 | Well-characterized activities, clinical relevance | Assay validation, drug repurposing, control compounds |

| Fragment Libraries | ~5,000 | Low molecular weight, high ligand efficiency | Fragment-based screening approaches |

The selection of compounds for inclusion in HTS libraries follows rigorous computational and empirical criteria to ensure chemical tractability and biological relevance. Initial curation typically involves standardized procedures where molecular structures are processed to clear charges, strip salts, canonicalize certain topologies, and select canonical tautomers [14]. These standardized molecules are then filtered through multiple steps:

- Lipinski's "Rule of Five" Filter: Selects compounds with molecular weight between 100-500 Daltons, ≤5 hydrogen bond donors, ≤10 hydrogen bond acceptors, and calculated logP (AlogP) between -5 and 5 [14].

- Formal Charge Filter: Retains molecules with formal charges between -3 and +3 after ionization using pKa models [14].

- REOS (Rapid Elimination of Swill) Filter: Eliminates compounds with functional groups deemed reactive or promiscuous based on literature and medicinal chemistry expertise [14].

- Diversity Selection: Uses Bayesian categorizers and chemical fingerprints to select compounds that maximize chemical diversity relative to existing internal collections [14].

Specialized libraries have emerged to address specific screening needs. For example, blood-brain barrier (BBB) penetrating libraries contain compounds predicted to cross the BBB based on specific physicochemical properties [14]. Natural product libraries offer unique structural diversity derived from biological sources, while fragment libraries comprise small molecules with high binding potential that serve as building blocks for more complex drug candidates [26]. The global compound libraries market, projected to reach $11,500 million by 2025 with a compound annual growth rate of 8.2%, reflects the critical importance of these chemical collections in modern drug discovery [26].

HTS Assay Platform and Automation

The execution of high-throughput screening relies on integrated technology platforms that combine specialized laboratory ware, automation systems, and detection methodologies to enable rapid and reproducible testing of compound libraries. The core physical platform for HTS is the microtiter plate, a disposable plastic container featuring a grid of small, open divots called wells [1]. Standard microplate formats include 96, 192, 384, 1536, 3456, or 6144 wells, all maintaining the fundamental 9 mm spacing paradigm established by the original 96-well plate [1]. The selection of plate format represents a balance between screening throughput, reagent consumption, and assay requirements, with higher density plates enabling greater throughput but requiring more sophisticated liquid handling capabilities.

Assay plates used in actual screening experiments are created from carefully catalogued stock plates through precise pipetting of small liquid volumes (often nanoliters) from stock plate wells to corresponding wells in empty assay plates [1]. This process maintains the integrity of the compound library organization while creating specialized plates optimized for specific screening assays. A typical HTS facility maintains a robust infrastructure for compound management and storage, utilizing systems such as Matrix and FluidX for storage and tracking, with Echo acoustic dispensing technology enabling precise source plate generation [27].

Table 2: Core Equipment in an Automated HTS Platform

| System Component | Representative Technologies | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Handling | Automated pipettors, acoustic dispensers | Transfer of compounds, reagents, and cells with precision and reproducibility |

| Robotics & Transport | Robotic arms, plate conveyors | Movement of microplates between workstations without human intervention |

| Detection & Readout | Multimode plate readers (fluorescence, luminescence, absorbance, TR-FRET, HTRF, AlphaScreen) | Measurement of biological responses and compound effects |

| Compound Management | Matrix, FluidX storage systems, barcoding | Storage, tracking, and retrieval of compound library plates |

| Data Processing | KNIME analytics platform, custom bioinformatics software | Statistical analysis, visualization, and hit identification |

Automation is the cornerstone of HTS efficiency, with integrated robot systems transporting assay microplates between dedicated stations for sample and reagent addition, mixing, incubation, and final readout [1]. Modern HTS systems can prepare, incubate, and analyze many plates simultaneously, dramatically accelerating data collection. Contemporary screening robots can test up to 100,000 compounds per day, with systems capable of screening in excess of 100,000 compounds per day classified as ultra-high-throughput screening (uHTS) [1]. Recent advances have further enhanced throughput and efficiency, with approaches like drop-based microfluidics enabling 100 million reactions in 10 hours at one-millionth the cost of conventional techniques by using picoliter fluid drops separated by oil instead of traditional microplate wells [1].

The assay technologies deployed in HTS platforms fall into two primary categories: biochemical assays and cell-based assays. Biochemical assays typically measure direct molecular interactions and include techniques such as fluorescence polarization (FP), time-resolved fluorescence resonance energy transfer (TR-FRET), ADP-Glo, and various enzymatic activity measurements [27]. Cell-based assays provide more physiologically relevant contexts and include GPCR and receptor-ligand binding assays (e.g., NanoBRET), cytotoxicity and proliferation measurements, and metabolite or biomarker detection methods like AlphaLISA [27]. Each assay type requires specialized optimization and validation to ensure robustness in the high-throughput environment.

Diagram 1: HTS workflow from library to hit.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Biochemical Inhibition Assay (384-well format)

This protocol describes a standardized approach for screening compound libraries against enzymatic targets using a fluorescence-based readout in 384-well microplates.

Materials:

- Assay buffer: 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 10 mM MgClâ‚‚, 1 mM DTT, 0.01% BSA

- Enzyme stock solution (purified target enzyme)

- Substrate solution (fluorogenic substrate)

- Compound library plates (10 mM in DMSO)

- Positive control inhibitor (reference compound)

- 384-well low-volume black microplates

- Multichannel pipettes or automated liquid handler

- Centrifuge with microplate adapters

- Multimode microplate reader capable of fluorescence detection

Procedure:

- Plate Preparation: Centrifuge compound library plates at 1,000 × g for 1 minute to collect liquid at the bottom of wells.

- Compound Transfer: Using an automated liquid handler, transfer 20 nL of compound from library plates to assay plates, resulting in final compound concentration of 10 μM after all additions.

- Enzyme Addition: Prepare enzyme solution in assay buffer at 2× final concentration. Add 10 μL of enzyme solution to all test and control wells using a multidispenser.

- Pre-incubation: Centrifuge assay plates briefly (500 × g for 30 seconds) and incubate at room temperature for 15 minutes to allow compound-enzyme interaction.

- Reaction Initiation: Prepare substrate solution at 2× final concentration in assay buffer. Add 10 μL of substrate solution to all wells to initiate reaction.

- Kinetic Measurement: Immediately transfer plates to pre-warmed microplate reader and measure fluorescence continuously every minute for 30 minutes using appropriate excitation/emission wavelengths.

- Data Collection: Record fluorescence values and calculate initial reaction velocities from linear portion of progress curves.

Quality Control:

- Include positive control wells (enzyme + substrate + control inhibitor) and negative control wells (enzyme + substrate + DMSO) in each plate.

- Calculate Z' factor for each plate using the formula: Z' = 1 - (3 × SDpositive + 3 × SDnegative) / |Meanpositive - Meannegative|

- Accept plates with Z' factor ≥ 0.5 for screening [1].

Protocol 2: Cell-Based Viability Assay (1536-well format)

This protocol describes a miniaturized cell-based screening approach for assessing compound effects on cell viability in 1536-well format, enabling high-throughput profiling.

Materials:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., cancer cell line)

- Cell culture medium with appropriate supplements

- Compound library plates (1 mM in DMSO)

- Viability assay reagent (e.g., luminescent ATP detection assay)

- 1536-well white solid-bottom microplates

- Automated liquid handling system capable of 1536-well format

- COâ‚‚ incubator for cell culture

- Luminescence microplate reader

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest exponentially growing cells, count, and resuspend in culture medium at 200,000 cells/mL.

- Cell Dispensing: Using an automated dispenser, add 5 μL of cell suspension to each well of 1536-well assay plates (1,000 cells/well).

- Plate Incubation: Incubate plates overnight (16-24 hours) in a humidified 37°C, 5% CO₂ incubator to allow cell attachment.

- Compound Addition: Transfer 10 nL of compound from library plates to assay plates using pintool or acoustic dispenser (final concentration: 1 μM).

- Treatment Incubation: Return plates to COâ‚‚ incubator for 72 hours to allow compound treatment effects.

- Viability Measurement: Remove plates from incubator and equilibrate to room temperature for 30 minutes.

- Assay Reagent Addition: Add 5 μL of viability assay reagent to each well using automated dispenser.

- Signal Development: Incubate plates at room temperature for 10 minutes to stabilize luminescent signal.

- Signal Detection: Measure luminescence using appropriate integration time on microplate reader.

Data Analysis:

- Normalize data using positive control wells (cells + DMSO, 100% viability) and negative control wells (cells + cytotoxic control, 0% viability).

- Calculate percent viability for each well: % Viability = (Compound Luminescence - Negative Control) / (Positive Control - Negative Control) × 100

- Identify hits as compounds showing <50% viability relative to controls.

Data Analysis and Hit Identification

The analysis of HTS data represents a critical phase where robust statistical methods are employed to distinguish true biological activity from experimental noise and to identify legitimate "hit" compounds for further investigation. The massive datasets generated by HTS – often comprising hundreds of thousands of data points – require specialized analytical approaches for quality control and hit selection [1]. The fundamental challenge lies in extracting biochemical significance from these extensive datasets while maintaining appropriate statistical stringency.

Quality Control Metrics

Quality control begins with effective plate design that incorporates appropriate controls to identify systematic errors, particularly those linked to well position [1]. Each screening plate typically includes multiple types of control wells:

- Positive controls: Contain a known active compound or maximal stimulus

- Negative controls: Contain only solvent (e.g., DMSO) or no stimulus

- Blank controls: Contain only reagents without biological components

Several statistical parameters have been adopted to evaluate data quality across screening plates:

- Signal-to-Background Ratio (S/B): S/B = MeanSignal / MeanBackground

- Signal-to-Noise Ratio (S/N): S/N = (MeanSignal - MeanBackground) / SD_Background

- Z' Factor: Z' = 1 - (3 × SDpositive + 3 × SDnegative) / |Meanpositive - Meannegative| [1]

The Z' factor has emerged as a particularly valuable metric, with values ≥ 0.5 indicating excellent assay quality, values between 0.5 and 0 indicating marginal quality, and values < 0 indicating poor separation between positive and negative controls [1]. More recently, Strictly Standardized Mean Difference (SSMD) has been proposed as an improved method for assessing data quality in HTS assays, particularly for RNAi screens [1].

Table 3: Statistical Methods for Hit Selection in HTS

| Method | Application Context | Calculation | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Z-score | Primary screens without replicates | z = (x - μ) / σ | Simple calculation, easily interpretable | Sensitive to outliers, assumes normal distribution |

| Z*-score | Primary screens without replicates | Uses median and MAD instead of mean and SD | Robust to outliers | Less powerful for normally distributed data |

| t-statistic | Confirmatory screens with replicates | t = (x - μ) / (s / √n) | Accounts for sample size | Affected by both effect size and sample size |

| SSMD | Screens with or without replicates | SSMD = (μ₠- μ₂) / √(σ₲ + σ₂²) | Directly measures effect size, comparable across experiments | More complex calculation |

Hit Selection Methods

The process of selecting hits – compounds with a desired size of effects – differs significantly between primary screens (typically without replicates) and confirmatory screens (with replicates) [1]. For primary screens without replicates, simple metrics such as average fold change, percent inhibition, and percent activity provide easily interpretable results but may not adequately capture data variability [1]. The z-score method, which measures how many standard deviations a compound's activity is from the mean of all tested compounds, is commonly employed but is sensitive to outliers [1].

Robust methods have been developed to address the limitation of traditional z-scores, including the z*-score method which uses median and median absolute deviation (MAD) instead of mean and standard deviation, making it less sensitive to outliers [1]. Other approaches include the B-score method, which accounts for spatial effects within plates, and quantile-based methods that make fewer distributional assumptions [1].

For screens with replicates, more sophisticated statistical approaches become feasible. The t-statistic is commonly used but has the limitation that it is affected by both sample size and effect size, and it is designed for testing hypothesis of no mean difference rather than measuring the size of compound effects [1]. SSMD has been shown to be superior for hit selection in screens with replicates as it directly assesses the size of effects and its population value is comparable across experiments, allowing use of consistent cutoff values [1].

Contemporary HTS platforms increasingly integrate cheminformatics and AI-driven tools that streamline data interpretation and compound triaging [27]. Automated workflows built on platforms like KNIME enable efficient statistical analysis and high-quality data visualization [27]. During the triage process, compounds are typically filtered using industry-standard false-positive elimination rules, including filters for pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS), rapid elimination of swill (REOS), and proprietary filters such as the Lilly filter [27]. Structure-based clustering techniques and structure-activity relationship (SAR)-driven prioritization then help narrow down large hit lists to those compounds with the highest drug-like potential [27].

Hit Confirmation and Triage