How to Interpret Dose-Response Curves: A Comprehensive Guide for Preclinical Research and Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on interpreting dose-response curves in preclinical research.

How to Interpret Dose-Response Curves: A Comprehensive Guide for Preclinical Research and Drug Development

Abstract

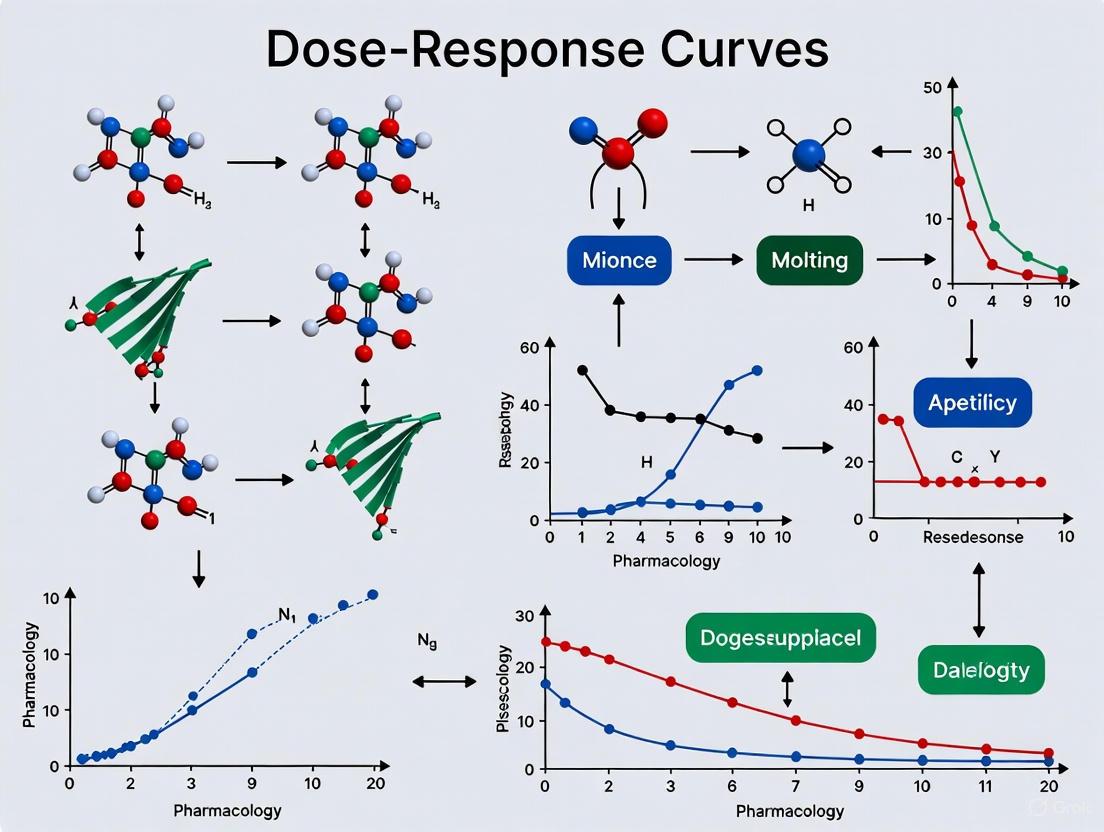

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on interpreting dose-response curves in preclinical research. It covers foundational principles, from defining key parameters like EC50, Emax, and Hill slope to understanding curve shapes and their biological significance. The guide delves into methodological applications, including step-by-step curve creation, mathematical modeling with Hill and Emax equations, and advanced model-based analysis techniques. It addresses common troubleshooting challenges in experimental design and data interpretation, and explores validation strategies through comparative analysis and meta-analysis. The content synthesizes modern best practices to enhance decision-making in lead optimization and clinical translation, emphasizing the critical role of robust dose-response characterization in successful drug development.

Decoding the Basics: Understanding Dose-Response Curve Fundamentals and Key Parameters

What is a Dose-Response Curve? Defining the Relationship Between Stimulus and Biological Effect

The dose-response relationship is a fundamental principle in pharmacology and toxicology that describes the quantitative relationship between the exposure amount or dose of a substance and the magnitude of the biological effect it produces [1] [2]. This systematic description analyzes what kind of response is generated at the administration of a specific drug dose and is central to determining "safe," "hazardous," and beneficial levels of drugs, pollutants, foods, and other substances to which humans or other organisms are exposed [1]. The well-known adage "the dose makes the poison" effectively captures this concept, reflecting how a small amount of a toxin may have no significant effect, while a large amount could prove fatal [1].

In preclinical research, understanding this relationship is crucial for optimizing clinical outcomes [3]. Dose-response curves are the graphical representations of these relationships, with the applied dose generally plotted on the X-axis and the measured response plotted on the Y-axis [1]. These curves serve as critical tools throughout the drug development pipeline, providing invaluable insights for regulatory documentation regarding efficacy and safety [4].

Key Components and Parameters of Dose-Response Curves

Quantitative Parameters of Dose-Response Curves

Dose-response analysis reveals several critical parameters that characterize compound activity. The following table summarizes these key quantitative measures:

| Parameter | Definition | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Potency | Amount of drug required to produce therapeutic effect [4] | Identifies lower effective dosing limits; more potent drugs require lower doses [4] |

| Efficacy (Emax) | Maximum therapeutic response a drug can produce [2] [4] | Determines upper limit of drug effect; distinguishes from potency [4] |

| EC50 | Concentration producing 50% of maximum effect in graded response [2] | Measures agonist potency; standard for comparison in high-throughput screening [1] [4] |

| IC50 | Concentration inhibiting biological process by 50% [4] | Characterizes antagonists/enzyme inhibitors; lower values indicate greater inhibitory potency [4] |

| Slope Factor | Steepness of the curve, quantified by Hill slope [1] | Indicates response sensitivity to dose changes; steeper slopes suggest higher potency at low concentrations [2] |

| Threshold Dose | Minimum dose where measurable response first occurs [2] | Establishes safety boundaries; defines safe vs. potentially harmful exposure levels [2] |

Mathematical Modeling of Dose-Response Relationships

The characteristic sigmoidal shape of many dose-response curves can be mathematically described by the Hill equation [1]. This logistic function models the relationship between drug concentration and effect:

Where:

- E = observed effect at concentration [A]

- Emax = maximum possible effect

- [A] = drug concentration

- EC50 = concentration producing half-maximal effect

- n = Hill coefficient (slope factor) [1]

For more flexible modeling, particularly when baseline effects must be considered, the Emax model is widely employed in drug development:

Where E0 represents the effect at zero dose [1]. This generalized model accommodates various baseline conditions and is the single most common non-linear model for describing dose-response relationships in drug development [1].

Curve Characteristics and Biological Interpretation

The Sigmoidal Curve and Its Phases

The majority of drug molecules follow a sigmoidal dose-response curve when response is plotted against the logarithm of the dose [4]. This characteristic S-shape emerges from biological principles and consists of three distinct phases:

- Lag Phase: At very low doses, the response is minimal because insufficient drug molecules are bound to receptors to trigger a significant biological effect [2] [4].

- Linear Phase: As the dose increases, the response rises steeply in an approximately linear fashion as more receptors become occupied, producing a progressively greater effect [4].

- Plateau Phase: The curve eventually flattens as receptor saturation occurs—all available receptors are occupied, and increasing the dose further cannot produce a greater biological effect [2] [4].

This sigmoidal shape reflects the biological limits of the system and effectively illustrates how drug efficacy develops over a range of doses [2] [4].

Multiphasic and Nonlinear Responses

Not all dose-response relationships follow simple sigmoidal patterns. Biological complexity often produces multiphasic curves that cannot be captured by the classical Hill equation [4]. Research analyzing 11,650 dose-response curves from the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia found that approximately 28% were more accurately modeled by multiphasic models [4].

The DOT language diagram below illustrates the workflow for identifying and modeling these complex curve types:

Complex curve types include two inhibitory phases, stimulation followed by inhibition, and three-phase curves [4]. These multiphasic responses may occur when a drug acts on multiple receptors with different sensitivities, exhibits dual effects (stimulatory at low doses and inhibitory at high doses), or when metabolic saturation occurs [4].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Preclinical Dose Range Finding (DRF) Studies

Dose range finding (DRF) studies form the foundation of preclinical drug development, providing crucial safety data to guide dose level selection before advancing into formal toxicology studies [5]. These studies establish two critical parameters: the minimum effective dose (MED) and the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) [5].

The experimental workflow for DRF studies can be visualized as follows:

Key Experimental Steps in DRF Studies

Animal Model Selection: Species selection (rodents and/or non-rodents) directly impacts the relevance and translational value of data for human risk assessment. Selection criteria include drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME) properties, receptor expression, and physiological relevance to humans [5].

Study Design and Dosing Strategies: A well-designed DRF study includes multiple dosing levels to establish a dose-response relationship. The starting dose is based on prior PK, PD, or in vitro studies, with gradual increases (e.g., 2x, 3x logarithmic increments) until significant toxicity is observed. If severe toxicity occurs, researchers may test intermediate doses to fine-tune the MTD [5].

Safety and Toxicity Assessments: Comprehensive monitoring includes clinical observations, body weight tracking, food consumption, and pathological assessments (hematology, serum chemistry, urinalysis). Gross necropsy followed by preliminary histopathology helps identify organ-specific toxicities [5].

Pharmacokinetics (PK) and Biomarker Evaluation: Measuring exposure metrics—maximum concentration (Cmax), area under the curve (AUC), and half-life—provides insights into dose-exposure relationships. Biomarkers evaluate target engagement and pharmacodynamic effects, offering early indicators of toxicities and confirming PD outcomes [5].

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

The following table details key research reagents and solutions essential for conducting dose-response experiments:

| Reagent/Solution | Function in Dose-Response Research |

|---|---|

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Provide biological context for measuring compound effects on living cells in high-throughput screening [4]. |

| Target-Specific Ligands | Agonists and antagonists used to characterize receptor binding and functional responses in pharmacological studies [4]. |

| Molecular Docking Tools | Computational methods to predict binding affinity of compounds to target proteins, informing dose-response modeling [6]. |

| Pathway-Specific Biomarkers | Measurable indicators of target engagement and pharmacodynamic effects at different dose levels [5]. |

| Analytical Standards | Certified reference materials for quantifying drug concentrations in PK studies measuring Cmax, AUC, and half-life [5]. |

Applications in Preclinical Research and Drug Development

Efficacy and Safety Assessment

Dose-response curves enable researchers to estimate both the minimum effective dose and maximum tolerated dose, establishing the therapeutic window where a drug is effective but not toxic [5] [4]. In toxicology, these curves identify critical safety parameters:

- No Observed Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL): The highest dose at which no harmful effects are observed [4].

- Lowest Observed Adverse Effect Level (LOAEL): The lowest dose where a harmful effect is detected [4].

These values are essential for regulatory filings and first-in-human (FIH) dose selection, helping to establish safe margins between efficacious and toxic doses [5].

Agonist and Antagonist Characterization

Dose-response curves critically differentiate how various drug types interact with biological systems:

- Agonists (which activate receptors) typically produce classical sigmoidal curves, with EC50 values indicating potency [4].

- Competitive antagonists (which block receptor activation) shift the agonist curve to the right, requiring higher agonist concentrations to achieve the same effect [4].

- Non-competitive antagonists not only shift the curve but also flatten it by reducing the maximum efficacy (Emax) [4].

Paradigm Shift in Oncology Dose Optimization

Traditional dose-finding for cytotoxic cancer drugs focused primarily on determining the maximum tolerated dose (MTD). However, for modern targeted therapies and immunotherapies, the field is shifting toward defining the optimal biological dose (OBD) that offers a better efficacy-tolerability balance [7]. This new paradigm incorporates PK/PD-driven modeling, biomarker data, and patient-reported outcomes to characterize the dose-response curve and identify a range of possible doses earlier in development [7].

The dose-response curve represents a fundamental conceptual framework in preclinical research, providing a systematic approach to understanding the quantitative relationship between drug exposure and biological effect. Through its key parameters—potency, efficacy, EC50/IC50, and slope—researchers can characterize compound activity, establish therapeutic windows, and identify optimal dosing strategies. The ongoing evolution from simple sigmoidal models to multiphasic frameworks reflects growing recognition of biological complexity, while advances in computational modeling and pathway network analysis offer promising approaches for predicting dose-response relationships in increasingly sophisticated biological systems. For preclinical researchers, mastery of dose-response principles remains essential for translating laboratory findings into safe and effective therapeutic interventions.

In preclinical drug development, the dose-response curve is a fundamental tool for quantifying the biological activity of a compound. This relationship, which is typically sigmoidal when response is plotted against the logarithm of concentration, provides a wealth of information that guides decision-making from early discovery through lead optimization [8] [9]. Proper interpretation of this curve allows researchers to predict therapeutic potential, understand mechanism of action, and identify promising candidates for further development. The curve's shape and position are characterized by three fundamental parameters: the EC50/IC50 (potency), Emax (efficacy), and Hill slope (cooperativity) [10] [11] [8]. This guide provides an in-depth examination of these critical parameters, their biological significance, and the experimental methodologies employed for their accurate determination in preclinical research.

Fundamental Parameters of Dose-Response Curves

EC50 and IC50: Quantifying Potency

The EC50 (half-maximal effective concentration) and IC50 (half-maximal inhibitory concentration) are quantitative measures of a compound's potency, representing the concentration required to produce 50% of the maximum effect or 50% inhibition of a biological process, respectively [12] [13]. In pharmacological terms, potency is defined as the concentration or dose of a drug required to produce 50% of that drug's maximal effect [14]. It is crucial to recognize that potency and efficacy are distinct concepts; a compound can be highly potent (low EC50) yet have limited efficacy (low Emax), or vice versa [14] [9].

The interpretation of these values requires careful consideration of what defines 100% and 0% response [12]. The relative EC50/IC50 is the most common definition, representing the concentration that produces a response halfway between the top and bottom plateaus of the experimental curve itself. In contrast, the absolute EC50/IC50 (sometimes referred to as GI50 in anti-cancer drug screening) is the concentration that produces a response halfway between the values defined by positive and negative controls [12] [15]. The relative definition forms the basis of classical pharmacological analysis, while the absolute approach is sometimes used in specialized contexts such as cell growth inhibition studies [12].

Emax: Quantifying Efficacy

Emax represents the maximum response achievable by a drug at sufficiently high concentrations, reflecting its intrinsic efficacy [14] [16] [8]. Efficacy describes the ability of a drug to initiate a cellular response once bound to its receptor, with higher Emax values indicating a greater capacity to elicit a biological effect [14]. In the context of receptor theory, efficacy expresses "the degree to which different agonists produce varying responses, even when occupying the same proportion of receptors" [14]. It is important to note that efficacy is highly dependent on experimental conditions, including the tissue used, level of receptor expression, and the specific measurement technique employed [14].

Hill Slope: Quantifying Cooperativity and Curve Steepness

The Hill slope (n), also known as the Hill coefficient, quantifies the steepness of the dose-response curve and can indicate cooperative interactions in drug-receptor binding [10] [11]. The Hill coefficient provides a way to quantify the degree of interaction between ligand binding sites [11]. The value of the Hill slope provides critical insights into the binding mechanism:

- n = 1.0: Suggests simple bimolecular binding with no cooperativity, typical of a ligand binding to a single independent receptor site [11] [17].

- n > 1.0: Indicates positive cooperativity, where binding of the first ligand molecule facilitates binding of subsequent molecules, resulting in a steeper curve [11].

- n < 1.0: Suggests negative cooperativity or multiple binding sites with different affinities, producing a shallower curve [11] [15].

Table 1: Key Parameters of Dose-Response Curves

| Parameter | Symbol | Definition | Interpretation | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Potency | EC50/IC50 | Concentration for 50% maximal effect/inhibition | Lower value = higher potency | pM-mM |

| Efficacy | Emax | Maximum achievable response | Higher value = greater efficacy | 0-100% |

| Cooperativity | Hill slope | Steepness of dose-response curve | n=1: no cooperativityn>1: positive cooperativityn<1: negative cooperativity | Typically 0.5-3 |

Mathematical Foundations: The Hill Equation

The relationship between drug concentration and effect is mathematically described by the Hill equation, originally formulated by Archibald Hill in 1910 to describe the sigmoidal O2 binding curve of hemoglobin [10] [11]. The equation has two closely related forms: one reflecting receptor occupancy and the other describing tissue response.

For tissue response, the Hill equation is expressed as:

[ E = E0 + E{max} \frac{C^n}{EC_{50}^n + C^n} ]

Where:

- (E) = observed biological effect

- (E_0) = baseline effect (can be fixed at 0 for simple models)

- (E_{max}) = maximum possible effect

- (C) = drug concentration

- (EC_{50}) = concentration producing 50% of maximal effect

- (n) = Hill coefficient [16]

This equation can be rearranged to illustrate why the curve is sigmoidal when plotted against log concentration:

[ E = \frac{E{max}}{1 + \exp(-n(\ln C - \ln EC{50}))} ]

This form demonstrates that the effect (E) is described by a logistic function of (\ln C), where (EC_{50}) acts as a location parameter and (n) as a gain parameter controlling steepness [16].

For data analysis, the equation can be linearized by creating a Hill plot:

[ \log\left(\frac{E}{E{max} - E}\right) = n(\log C - \log EC{50}) ]

A plot of (\log(E/(E{max} - E))) versus (\log C) yields a straight line with slope (n) and x-intercept of (\log EC{50}) [11]. However, with modern computing power, nonlinear regression is preferred as it provides more robust parameter estimates without distorting error propagation [11].

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Determination

Saturation Binding Assays for Kd and Bmax Determination

Objective: To determine the equilibrium dissociation constant (Kd) and maximum number of binding sites (Bmax) for a ligand-receptor interaction.

Protocol:

- Receptor Preparation: Prepare membrane fractions or cells expressing the target receptor.

- Radioligand Dilution: Prepare a concentration series of radiolabeled ligand, typically spanning a 100-10,000-fold range centered around the estimated Kd.

- Incubation: Incubate each radioligand concentration with a fixed amount of receptor preparation in appropriate buffer. Include parallel tubes with excess unlabeled ligand (100x Kd) to determine nonspecific binding.

- Separation and Measurement: Separate bound from free ligand by rapid filtration, centrifugation, or other appropriate method. Measure bound radioactivity by scintillation counting.

- Data Analysis: Subtract nonspecific binding from total binding to obtain specific binding. Fit specific binding data to the equation:

[ Y = B{max} \times X^h / (Kd^h + X^h) ]

Where Y is specific binding, X is radioligand concentration, Bmax is maximum binding sites, Kd is equilibrium dissociation constant, and h is Hill slope [17].

Functional Dose-Response Assays for EC50/IC50 and Emax Determination

Objective: To determine the functional potency (EC50/IC50) and efficacy (Emax) of a compound in a biological system.

Protocol:

- Cell/ Tissue Preparation: Prepare cells expressing the target receptor or isolated tissue responsive to the compound.

- Compound Dilution: Prepare serial dilutions of the test compound, typically in log increments (e.g., half-log or full-log dilutions) across a range covering expected inactive to maximal effect concentrations.

- Response Measurement: Apply compound concentrations to the biological system and measure the functional response (e.g., cAMP accumulation, calcium flux, cell viability, contraction force).

- Control Definition: Include appropriate controls to define 0% and 100% response:

- For agonists: Use vehicle control (0%) and maximal concentration of standard agonist (100%)

- For antagonists/ inhibitors: Use vehicle control (0%) and maximal concentration of standard inhibitor (100%) [12]

- Data Analysis: Fit normalized response data to the Hill equation using nonlinear regression algorithms such as Levenberg-Marquardt [10]. For incomplete curves that don't reach plateaus, constraints may be applied based on control values [12].

Data Normalization and Quality Control

Proper normalization is critical for accurate parameter estimation. The three main strategies include:

- External controls: Using separately measured positive and negative controls to define 100% and 0% response [10] [12].

- Extreme concentrations: Using the lowest and highest concentrations of the test substance to define response limits [12].

- Regression plateaus: Using the top and bottom plateau values estimated from nonlinear regression [12].

Fit validation should include assessment of:

- Activity threshold: Setting ranges that define inactive compounds to prevent bogus IC50 calculations for compounds with insufficient activity [10].

- Parameter constraints: Restricting parameters to physiologically plausible ranges when appropriate [10].

- Curve quality metrics: Evaluating R-squared values, confidence intervals of parameters, and visual inspection of residuals [10].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for dose-response analysis.

Advanced Interpretation and Biological Significance

Relationship Between Binding and Response

While the Hill equation can describe both receptor binding and functional response, it is crucial to recognize that Kd (binding affinity) and EC50 (functional potency) are not identical parameters [13] [9]. The relationship between occupancy and response is often nonlinear due to signal amplification mechanisms in biological systems [16]. A drug may bind tightly to its receptor (low Kd) yet produce a weak response (high EC50) if it has low efficacy, or conversely, bind weakly yet produce a strong response if the system has high amplification [16] [13].

This distinction has practical implications for drug discovery. A common mistake is assuming that a lower IC50 always means stronger binding, when in fact IC50 depends on experimental conditions, and two compounds with the same Kd could have very different IC50 values in different assays [13]. Kd is better for understanding pure binding affinity, while EC50/IC50 are more relevant for functional inhibition or activation in specific biological contexts [13].

Systematic Variation in Parameters Across Biological Contexts

Different dose-response parameters can vary systematically depending on biological context, carrying distinct information about drug action [15]. In large-scale analyses of anti-cancer drug responses:

- Emax frequently associates with cell type, particularly correlating with cell proliferation rate for cell-cycle inhibitors [15].

- Hill slope often associates with drug class, with certain target classes (e.g., Akt/PI3K/mTOR inhibitors) consistently showing unusually shallow curves (Hill slope < 1) [15].

- IC50 shows variable association with both cell type and drug class, but is often less informative than multi-parametric analysis [15].

These systematic variations highlight why multi-parameter analysis provides more comprehensive insights than potency (IC50) alone, particularly at clinically relevant concentrations near and above IC50 [15].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Dose-Response Studies

| Reagent/Category | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Radiolabeled Ligands | Quantitative measurement of receptor binding affinity (Kd) and density (Bmax) | Saturation binding assays; competition binding studies |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Define 0% and 100% response for data normalization | Reference agonists/antagonists; vehicle controls |

| Cell Viability Assays | Measure functional responses in cellular systems | ATP-based assays (CellTiter-Glo); apoptosis markers |

| Signal Transduction Assays | Quantify downstream signaling events | cAMP accumulation; calcium flux; phosphorylation status |

| Enzyme/Receptor Preparations | Source of molecular targets | Recombinant enzymes; membrane preparations; cell lines |

Clinical Relevance and Therapeutic Implications

The parameters derived from dose-response curves have direct clinical relevance. Potency (EC50) influences dosing regimens, with more potent drugs typically requiring lower doses to achieve therapeutic effects [9]. Efficacy (Emax) determines the maximum therapeutic benefit achievable with a drug, which is particularly important for diseases requiring strong pharmacological intervention [14] [9]. The Hill slope affects the therapeutic window, as steeper curves (Hill slope > 1) result in a narrower range between ineffective and toxic concentrations [11] [9].

For therapeutic use, it is essential to distinguish between potency and efficacy. A drug may be potent (low EC50) but have limited clinical utility if its maximum efficacy is insufficient for the therapeutic goal [9]. Conversely, a less potent drug with higher maximum efficacy may be more effective at achievable concentrations [9].

Diagram 2: Relationship between drug binding and physiological response.

The comprehensive interpretation of EC50/IC50, Emax, and Hill slope provides critical insights that extend far beyond simple potency rankings. These parameters collectively describe fundamental aspects of drug action: the concentration required for effect (potency), the maximum achievable response (efficacy), and the cooperative nature of the interaction (steepness). Proper experimental design, rigorous data analysis, and multi-parameter interpretation are essential for accurate compound characterization in preclinical research. By moving beyond simplistic IC50 comparisons to embrace the full richness of information contained in dose-response relationships, researchers can make more informed decisions in the drug discovery process, ultimately leading to better candidate selection and improved clinical translation.

In preclinical drug development, the dose-response relationship is a fundamental principle that describes the correlation between the magnitude of a pharmacological effect and the dose or concentration of a drug administered to a biological system [1]. These relationships are crucial for determining "safe," "hazardous," and beneficial exposure levels for drugs and other substances [1]. Understanding these relationships forms the basis for public health policy and clinical trial design [18]. The dose-response relationship, when graphically represented, produces characteristic curves whose shapes reveal critical information about drug potency, efficacy, and mechanism of action [19]. The accurate interpretation of these curve shapes—primarily sigmoidal, linear, and biphasic—is therefore essential for optimizing therapeutic interventions and predicting clinical outcomes.

The analysis of dose-response curves extends across multiple levels of biological organization, from molecular interactions and cellular responses to whole-organism physiology and population-level effects [1]. At each level, the curve shape reflects the underlying biological processes and can be influenced by factors such as receptor binding kinetics, signal transduction pathways, metabolic processes, and homeostatic mechanisms [20]. For preclinical researchers, properly characterizing these curves enables the identification of optimal dosing ranges, prediction of potential toxicities, and selection of promising drug candidates for further development [18]. This guide provides a comprehensive technical framework for interpreting the most common dose-response curve shapes encountered in preclinical research, with emphasis on their biological implications and methodological considerations for accurate characterization.

Fundamental Concepts and Parameters

Before examining specific curve shapes, it is essential to understand the key parameters used to quantify dose-response relationships. These parameters provide the quantitative framework for comparing different compounds and interpreting their biological effects.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Characterizing Dose-Response Relationships

| Parameter | Description | Biological Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Potency | Location of curve along dose axis [19] | Concentration required to elicit a response; indicates binding affinity |

| Maximal Efficacy (Emax) | Greatest attainable response [19] | Maximum biological effect achievable with a compound; reflects intrinsic activity |

| Slope | Change in response per unit dose [19] | Steepness of transition from minimal to maximal response; indicates cooperativity |

| EC50/IC50 | Concentration producing 50% of maximal effect [21] | Standard measure of potency for agonists (EC50) or antagonists (IC50) |

| Hill Coefficient (nH) | Parameter describing steepness of sigmoidal curve [1] | Quantitative measure of cooperativity in binding; nH > 1 suggests positive cooperativity |

These parameters are derived through mathematical modeling of experimental data, with the Hill equation and Emax model being commonly used approaches [1]. The Hill equation is particularly valuable for sigmoidal curves and is expressed as E/Emax = [A]^n/(EC50^n + [A]^n), where E is the effect, Emax is the maximal effect, [A] is the drug concentration, EC50 is the concentration producing 50% of maximal effect, and n is the Hill coefficient [1]. The Emax model extends this concept by incorporating a baseline effect (E0) and is expressed as E = E0 + ([A]^n × Emax)/([A]^n + EC50^n) [1]. These models enable researchers to quantify dose-response relationships and make meaningful comparisons between different compounds and experimental conditions.

Sigmoidal Dose-Response Curves

Characteristics and Biological Basis

Sigmoidal curves represent the most frequently observed shape in dose-response relationships, particularly when the dose axis is plotted on a logarithmic scale [21]. These curves are characterized by a gradual increase at low doses, a steep, approximately linear rise at intermediate doses, and a plateau at higher doses [19]. The sigmoidal shape reflects fundamental biological principles, including the law of mass action for receptor-ligand interactions and the concept of occupancy-response relationships [1]. At low concentrations, the response is minimal as few receptors are occupied. As concentration increases, receptor occupancy rises rapidly, leading to a proportional increase in effect. At high concentrations, the response plateaus as receptors become saturated, representing the system's maximal capacity to respond.

The mathematical foundation for sigmoidal curves is often described by the Hill equation or four-parameter logistic (4PL) model, which quantifies the bottom asymptote (basal response), top asymptote (maximal response), slope factor (steepness), and EC50 (potency) [21]. The Hill slope provides valuable information about the cooperativity of the interaction; a slope greater than 1 suggests positive cooperativity, where binding of one ligand molecule facilitates binding of subsequent molecules, while a slope less than 1 may indicate negative cooperativity or system heterogeneity [1]. In receptor pharmacology, the sigmoidal shape reflects the transition from minimal receptor occupancy to saturation, with the steepness of the curve influenced by the degree of spare receptors and the efficiency of signal transduction mechanisms [19].

Experimental Protocol for Characterizing Sigmoidal Responses

The reliable characterization of sigmoidal dose-response relationships requires careful experimental design and execution. The following protocol outlines key methodological considerations:

Dose Selection and Spacing: Select 5-10 concentrations distributed across a broad range to adequately characterize the lower plateau, linear phase, and upper plateau of the curve [21]. Doses should be spaced appropriately, often using logarithmic increments (e.g., 1, 10, 100, 1000 nM) to better visualize the sigmoidal shape and distribute data points equally across the curve [21].

Response Measurement: Quantify effects under steady-state conditions or at the time of peak effect to establish a consistent dose-response relationship independent of time [19]. Responses can be measured at various biological levels, including molecular interactions (e.g., receptor binding), cellular responses (e.g., proliferation, death), tissue effects (e.g., muscle contraction), or whole-organism outcomes (e.g., blood pressure changes) [1].

Data Transformation: Apply logarithmic transformation to dose values when concentrations span several orders of magnitude [21]. Response data may be normalized to percentage values, with the minimum and maximum control responses set to 0% and 100%, respectively, to facilitate comparison across experiments [21].

Curve Fitting: Implement nonlinear regression analysis using appropriate models such as the four-parameter logistic (4PL) equation: Y = Bottom + (Top - Bottom)/(1 + 10^((LogEC50 - X) × HillSlope)), where X is the logarithm of concentration and Y is the response [21]. Constrain parameters when necessary based on biological plausibility (e.g., fixing the bottom plateau to 0% for essential processes) [21].

Parameter Estimation: Derive key parameters including EC50/IC50, Hill slope, and maximal efficacy from the fitted curve [21]. Evaluate the reliability of these estimates by assessing confidence intervals and goodness-of-fit measures.

Quality Assessment: Verify that the fitted curve adequately describes the data points, with the EC50/IC50 falling within the tested concentration range and plateaus reasonably aligned with control values [21].

Diagram 1: Experimental workflow for characterizing sigmoidal dose-response relationships, showing key steps from experimental design through data analysis and quality assessment.

Research Reagent Solutions for Sigmoidal Response Experiments

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Dose-Response Experiments

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Agonists | Full agonists (e.g., nicotine, isoprenaline) [1] | Elicit stimulatory or inhibitory responses; used to characterize receptor activation |

| Antagonists | Competitive antagonists (e.g., propranolol) [1] | Inhibit agonist effects; used to determine receptor specificity and mechanism |

| Allosteric Modulators | Benzodiazepines [1] | Bind to separate sites to enhance or reduce receptor responses; probe complex pharmacology |

| Cell Viability Assays | MTT, ATP-based assays [22] | Quantify cellular responses to drug treatments; measure cytotoxicity or proliferation |

| Signal Transduction Reporters | Calcium-sensitive dyes, cAMP assays [1] | Monitor intracellular signaling events downstream of receptor activation |

| Radioligands | ^3H- or ^125I-labeled compounds [23] | Directly measure receptor binding parameters (affinity, density) |

Linear Dose-Response Curves

Characteristics and Biological Context

Linear dose-response relationships demonstrate a direct proportionality between dose and effect across the tested concentration range without apparent saturation [24]. Unlike sigmoidal curves, linear relationships lack distinct plateaus and inflection points, resulting in a straight-line relationship when plotted on arithmetic coordinates. In preclinical research, linear responses are frequently observed in studies of nutrient effects, essential mineral supplementation, or toxicant exposure within limited concentration ranges [25]. The linear no-threshold (LNT) model, particularly relevant in radiation toxicology, represents a specific application of linear dose-response relationships that assumes cancer risk increases proportionally with dose without a threshold [1].

The biological interpretation of linear relationships varies significantly by context. In some cases, linearity reflects a system with vast receptor capacity or metabolic processes that have not reached saturation within the tested range [19]. In complex interventions such as psychotherapy research, linear relationships may emerge in the Good Enough Level (GEL) model, where the rate of improvement shows a linear relationship with the number of therapy sessions, though the strength of this relationship may vary with total dose [24]. It is important to note that apparent linearity may sometimes result from testing a limited range of concentrations that captures only the central portion of what would otherwise be a sigmoidal relationship.

Methodological Considerations for Linear Relationships

The accurate characterization of linear dose-response relationships presents distinct methodological challenges:

Range Determination: Establish that the tested concentrations adequately represent the biologically relevant range, as linear relationships may transition to nonlinear patterns (plateaus or declines) outside the observed window [21].

Model Selection: Apply appropriate statistical models, including linear regression (Y = a + bX) or random coefficient models for longitudinal data [24]. For repeated measures, multilevel modeling approaches can account for within-subject correlations [24].

Threshold Testing: Evaluate whether the relationship truly lacks a threshold by testing concentrations approaching zero effect. The potential for threshold effects should be carefully considered, as their presence would invalidate strict linearity [1].

Causal Inference: Exercise caution in interpreting linear relationships from observational data, as apparent dose-response patterns may reflect confounding factors rather than causal relationships [24]. Randomized designs strengthen causal interpretations.

Biphasic Dose-Response Curves

Characteristics and Hormetic Responses

Biphasic dose-response curves, characterized by two distinct response phases—typically low-dose stimulation and high-dose inhibition—represent biologically complex relationships that challenge traditional monotonic models [25]. This phenomenon, often termed hormesis, manifests as an adaptive overcompensation to low-level stressor exposure, followed by the expected toxic effects at higher doses [25]. The most consistent quantitative feature of hormetic-biphasic dose responses is the modest stimulatory response, typically only 30-60% greater than control values, observed across biological models, levels of organization, and endpoints [25]. This consistent quantitative signature suggests common underlying mechanisms related to adaptive biological responses.

The biological basis for biphasic responses involves the activation of compensatory processes at low doses that become overwhelmed at higher exposures [25]. In multi-site phosphorylation systems, for example, biphasic responses can emerge from distributive mechanisms involving a single kinase/phosphatase pair, where a hidden competing effect creates the characteristic low-dose stimulation and high-dose inhibition [25]. Similarly, in low-level laser (light) therapy, biphasic patterns observed in vitro (e.g., in ATP production and mitochondrial membrane potential) and in vivo (e.g., in neurological effects in traumatic brain injury models) reflect the Janus nature of reactive oxygen species, which act as beneficial signaling molecules at low concentrations but become harmful cytotoxic agents at high concentrations [25].

Experimental Protocols for Biphasic Response Characterization

The reliable detection and quantification of biphasic dose-response relationships require specialized methodological approaches:

Expanded Dose Range: Implement extended dose ranges that include very low concentrations (often below traditional testing levels) to adequately capture the stimulatory phase [25]. The hormetic zone may shift depending on experimental conditions, requiring careful range-finding studies.

Increased Replication: Enhance statistical power through increased replication, particularly at potential transition points between phases, as biphasic responses often exhibit subtle effects that may be obscured by experimental variability.

Alternative Modeling Approaches: Employ flexible modeling strategies that can accommodate non-monotonicity, such as Gaussian process regression or multiphasic functions [22] [26]. These approaches can quantify uncertainty and identify complex curve shapes without strong a priori assumptions.

Mechanistic Investigation: Design follow-up experiments to elucidate underlying mechanisms when biphasic responses are observed. This may include measuring adaptive response markers, stress pathway activation, or feedback inhibition processes.

Diagram 2: Proposed biological mechanism for biphasic (hormetic) dose-response relationships, showing the transition from adaptive stimulation at low doses to toxicity at high doses.

Complex Biphasic Patterns in Experimental Systems

Biphasic responses manifest across diverse experimental systems, each with distinct methodological implications:

Radiation Exposure: Triphasic dose responses comprising ultra-low-dose inhibition, low-dose stimulation, and high-dose inhibition have been observed in zebrafish embryos exposed to X-rays, with the hormetic zone shifting toward lower doses with application of filters [25]. This pattern suggests that previously reported biphasic responses might represent incomplete characterization of more complex triphasic relationships.

Alcohol Effects: The acute biphasic effects of alcohol on probability discounting (decision-making under uncertainty) vary across the ascending and descending limbs of the blood alcohol concentration curve, reflecting differential engagement of stimulatory and sedative processes [25]. This temporal dimension adds complexity to biphasic response characterization.

Insulin Signaling: Natural systems exploit differential dose responses, as demonstrated by insulin receptors that recognize various ligands with different binding affinities to trigger appropriate metabolic or mitogenic responses through biphasic mechanisms [20].

Comparative Analysis and Interpretation Framework

Integrated Comparison of Curve Shapes

Table 3: Comprehensive Comparison of Dose-Response Curve Shapes

| Characteristic | Sigmoidal | Linear | Biphasic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shape Description | S-shaped curve with lower plateau, steep phase, upper plateau | Straight-line relationship between dose and response | Two distinct phases: low-dose stimulation, high-dose inhibition |

| Key Parameters | EC50/IC50, Hill slope, Emax, baseline | Slope, intercept | Transition dose, maximum stimulation, inhibition parameters |

| Biological Interpretation | Receptor saturation, cooperative binding | Unsaturated systems, additive effects | Adaptive responses, overload mechanisms |

| Common Contexts | Receptor-ligand interactions, enzyme kinetics [1] | Nutrient effects, radiation risk (LNT) [1] | Hormesis, low-level stress responses [25] |

| Experimental Considerations | 5-10 doses, logarithmic spacing [21] | Linear spacing may suffice | Expanded low-dose range, increased replication [25] |

| Modeling Approaches | Hill equation, 4PL, Emax model [1] [21] | Linear regression, random coefficients | Gaussian processes, multiphasic models [22] |

| Potential Pitfalls | Misinterpretation with limited dose range | Assumption of linearity beyond tested range | Overinterpretation of variable data |

Decision Framework for Curve Interpretation

The accurate interpretation of dose-response curves in preclinical research requires a systematic approach that considers both experimental design factors and biological context:

Range Assessment: Evaluate whether the tested concentration range adequately captures the biologically relevant spectrum. Incomplete curves (missing plateaus for sigmoidal relationships or transition zones for biphasic responses) represent a common source of misinterpretation [21].

Model Selection Criteria: Choose appropriate models based on biological plausibility, statistical fit, and parameter stability. For novel compounds without established mechanisms, flexible approaches such as Gaussian process regression can quantify uncertainty and identify unexpected curve shapes [22].

Context Integration: Consider system-specific factors that influence curve shape, including exposure duration, metabolic pathways, homeostatic mechanisms, and feedback loops. Dose-response relationships may vary significantly with exposure time and route [1].

Validation Strategies: Implement confirmatory experiments using orthogonal approaches when unexpected curve shapes emerge. For example, biphasic responses should be verified through mechanistic studies exploring proposed adaptive processes [25].

Reporting Standards: Document complete methodological details, including dose selection rationale, spacing, replication, normalization procedures, and model constraints, to enable accurate interpretation and replication [21].

The interpretation of dose-response curve shapes—sigmoidal, linear, and biphasic—represents a critical competency in preclinical drug development. Each curve shape provides distinct insights into compound potency, efficacy, and mechanism of action, with direct implications for lead optimization, toxicity assessment, and clinical translation. Sigmoidal curves, the most prevalent in pharmacology, reveal saturation kinetics and cooperative binding through their characteristic parameters. Linear relationships, while less common in receptor pharmacology, emerge in specific contexts including nutrient effects and radiation risk modeling. Biphasic curves challenge traditional monotonic paradigms and highlight the complex adaptive capacity of biological systems.

The reliable characterization of these relationships demands rigorous experimental design, appropriate statistical modeling, and nuanced biological interpretation. As drug development increasingly focuses on targeted therapies and complex biological systems, advanced methodological approaches including model-based inference, Bayesian frameworks, and uncertainty quantification will enhance the accurate interpretation of dose-response relationships [18] [22]. By applying the principles and protocols outlined in this technical guide, preclinical researchers can optimize compound selection, elucidate mechanisms of action, and strengthen the foundation for clinical translation, ultimately advancing therapeutic development through more sophisticated interpretation of dose-response curves.

In preclinical drug development, the dose-response curve is a fundamental tool for quantifying drug-receptor interactions and predicting therapeutic potential. These curves graphically represent the relationship between the concentration of a drug and the magnitude of its effect on a biological system [27]. The precise morphology of these curves—their position, slope, and maximum height—provides critical information about a compound's pharmacological activity, potency, and efficacy. Proper interpretation of these parameters allows researchers to classify drugs as agonists, antagonists, or more complex variants, and to predict their behavior in more complex biological systems [28].

The analysis of curve morphology extends beyond simple classification. Through quantitative methods like Schild analysis, researchers can determine fundamental constants describing drug-receptor interactions, particularly the equilibrium dissociation constant (KB) for competitive antagonists [27]. This guide details how different drug types mechanistically influence dose-response curve morphology and provides the methodological framework for its accurate interpretation in preclinical research.

Core Pharmacological Concepts

Defining Agonists and Antagonists

At the most fundamental level, drugs interacting with receptors can be categorized based on their intrinsic activity:

- Agonists: Molecules that bind to a receptor (affinity) and activate it to produce a cellular response (intrinsic efficacy) [28]. A full agonist produces the maximal system response, while a partial agonist produces a submaximal response, even at full receptor occupancy [29].

- Antagonists: Molecules that bind to the receptor (affinity) but possess zero intrinsic efficacy. They block or dampen the effect of an agonist but produce no effect themselves [28] [29].

- Inverse Agonists: A special class that binds to receptors and suppresses their basal, constitutive (spontaneous) activity, producing an effect opposite to that of an agonist [29].

Advanced Concepts: Constitutive Activity and Functional Selectivity

Modern pharmacology has moved beyond the simple agonist-antagonist dichotomy. Two key concepts refine our understanding:

- Constitutive Receptor Activity: Traditional theory held that receptors are quiescent until activated by a ligand. It is now established that many receptors can spontaneously adopt an active state and signal in the absence of an agonist [29]. This constitutive activity is a system-dependent property that can influence dose-response curves.

- Functional Selectivity (Biased Agonism): A single drug, acting at one receptor subtype, can have multiple intrinsic efficacies that differ depending on which downstream signaling pathway is measured. This means a drug can simultaneously act as an agonist for one pathway and an antagonist for another pathway coupled to the same receptor [29].

Quantitative Analysis of Curve Morphology

The Impact of Agonists on Curve Morphology

Agonists define the control dose-response curve from which all antagonism is measured. The key parameters derived from this curve are:

- Potency (EC50): The concentration of agonist that produces 50% of the maximal response. A lower EC50 indicates higher potency.

- Efficacy (Emax): The maximal response achievable by the agonist.

The intrinsic efficacy of an agonist primarily influences the Emax of the curve. A full agonist will produce the system's maximum response, while a partial agonist will produce a submaximal Emax [29]. The affinity of the agonist primarily influences the EC50 value.

The Impact of Antagonists on Curve Morphology

Antagonists alter the agonist's dose-response curve in characteristic ways that reveal their mechanism of action. The quantitative differences are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Quantitative Impact of Antagonist Types on Agonist Dose-Response Curves

| Antagonist Type | Mechanism of Action | Effect on Agonist EC50 | Effect on Agonist Emax | Surmountable by Agonist? |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competitive Reversible | Binds reversibly to the same site as the agonist [28]. | Increases (rightward shift) [27] [28]. | No change [28]. | Yes [28]. |

| Competitive Irreversible | Binds irreversibly to the agonist binding site [28]. | Increases. | Decreases [28]. | No [28]. |

| Non-competitive | Binds to an allosteric site, impairing receptor function without blocking agonist binding [28]. | May or may not change. | Decreases [28]. | No [28]. |

Schild Analysis: The Gold Standard for Quantifying Competitive Antagonism

For reversible competitive antagonists, Schild analysis is the preferred method for determining the antagonist's equilibrium constant (KB), a system-independent measure of its affinity [27]. This method is superior to simpler measures like the IC50, which is highly dependent on the experimental conditions, such as the concentration of agonist used [27].

Experimental Protocol for Schild Analysis:

- Generate a control curve: Construct a full dose-response curve for the agonist in the absence of antagonist.

- Generate shifted curves: Repeat the agonist dose-response curve in the presence of at least three different, fixed concentrations of the antagonist [27].

- Calculate the dose ratio (r): For each antagonist concentration [B], calculate the dose ratio at the EC50 level:

r = EC<sub>50,antagonist</sub> / EC<sub>50,control</sub>. - Construct the Schild plot: Plot

log(r - 1)versuslog[B]. - Determine KB: If the plot is linear with a slope of 1, the antagonism is competitive. The X-intercept is equal to

-log(K<sub>B</sub>), allowing direct calculation of the KB [27].

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key outputs of Schild analysis:

Experimental Protocols and the Scientist's Toolkit

Key Methodologies for Curve Generation

Reliable dose-response data requires rigorous experimental design. Below are detailed protocols for core methodologies.

Protocol 1: Functional Dose-Response Curve Assay (e.g., for a Gαs-Coupled GPCR)

- Cell Preparation: Culture cells expressing the target receptor. Seed into multi-well plates at a density ensuring sub-confluent growth at the time of assay.

- Agonist Dilution Series: Prepare a stock solution of the agonist and perform serial dilutions (typically 1:3 or 1:10) in assay buffer to create a concentration range covering expected sub-threshold to maximal effects. Include a vehicle control.

- Stimulation and Response Measurement:

- For a cAMP assay, replace medium with stimulation buffer containing phosphodiesterase inhibitor.

- Add agonist dilutions to respective wells and incubate for a predetermined time (e.g., 30 min at 37°C).

- Lyse cells and quantify accumulated cAMP using a HTRF, ELISA, or AlphaScreen kit according to the manufacturer's instructions.

- Data Analysis: Normalize response data as a percentage of the maximal agonist response. Fit the log(agonist) vs. response data to a four-parameter logistic equation to determine EC50 and Emax.

Protocol 2: Schild Analysis for Antagonist Characterization

- Control Curve: Perform Protocol 1 to generate a control agonist curve.

- Antagonist Pre-incubation: Prepare separate cell samples with at least three increasing concentrations of the antagonist. Include a vehicle control for the antagonist. Pre-incubate for a time sufficient to reach equilibrium (e.g., 30-60 min).

- Agonist Challenge in Antagonist Presence: Without washing out the antagonist, generate a full agonist dose-response curve in each pre-incubated sample, as in Protocol 1.

- Data Processing and Schild Plot Construction: Follow the calculation and plotting steps outlined in Section 3.3.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful execution of these protocols depends on high-quality reagents. Table 2 details essential materials and their functions.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Dose-Response Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Clonal Cell Line | Engineered to stably express the human target receptor, ensuring a consistent, reproducible system for screening and characterization [29]. |

| Reference Agonist | A well-characterized full agonist (e.g., Isoprenaline for β-adrenoceptors) used to define the system's maximum response and for benchmarking test compounds [27]. |

| Reference Antagonist | A known competitive antagonist for the target (e.g., Propranolol for β-adrenoceptors) used as a positive control in antagonism assays and for validating the Schild analysis method [27]. |

| Signal Detection Kit | Commercial kits (e.g., HTRF, ELISA) for quantifying second messengers (cAMP, IP1, Ca2+). Essential for measuring functional receptor activation with high sensitivity and throughput. |

| Fluorescent Probes | Radioactive or fluorescently labeled ligand analogs for performing binding studies to directly determine ligand affinity (KD) and receptor density (Bmax). |

| JR-AB2-011 | JR-AB2-011, CAS:2411853-34-2, MF:C17H14Cl2FN3OS, MW:398.28 |

| ELN318463 racemate | ELN318463 racemate, CAS:851600-86-7, MF:C19H20BrClN2O3S, MW:471.79 |

Visualizing Receptor Signaling Pathways

The interaction between a drug and its receptor is only the first step in a cascade of events that leads to a measurable response. The following diagram illustrates the core signaling pathways involved, highlighting the points where different drug types exert their influence.

The meticulous analysis of dose-response curve morphology remains a cornerstone of preclinical pharmacology. Understanding the characteristic shifts and depressions caused by antagonists, and rigorously quantifying these effects via Schild analysis, provides indispensable insights into mechanism of action and drug affinity [27]. Furthermore, incorporating modern concepts like constitutive activity and functional selectivity is no longer optional for comprehensive drug characterization [29]. These principles explain complex behaviors that traditional models cannot, such as how a drug can act as an agonist in one tissue and an antagonist in another. Mastery of these concepts and techniques ensures that researchers can accurately interpret complex biological data, de-risk drug development projects, and select the most promising candidates for advancement into clinical trials.

The Importance of Threshold Doses and the Linear No-Threshold Model Debate

In preclinical drug development, determining the relationship between the dose of a compound and its resulting biological effect is a fundamental task. This dose-response relationship is critical for understanding a drug's efficacy, safety, and therapeutic window [30]. The conceptual models used to interpret these relationships have profound implications for risk assessment and therapeutic optimization. The linear no-threshold (LNT) model represents one end of the theoretical spectrum, postulating that any dose greater than zero carries some risk, with response increasing linearly from the origin without a threshold [31] [32]. This model stands in contrast to threshold models, which propose the existence of a dose level below which no significant adverse effect occurs, and hormetic models, which suggest that very low doses may actually produce beneficial stimulatory effects [31] [32].

The debate between these models extends beyond theoretical interest, directly impacting how researchers design experiments, interpret data, and establish safety margins for clinical translation. For drug development professionals, this debate influences decisions ranging from initial compound screening to final dose justification for regulatory submission [30]. Approximately 16% of drugs that failed their first FDA review cycle were rejected due to uncertainties in dose selection rationale, highlighting the critical importance of accurate dose-response characterization [30]. Furthermore, about 20% of FDA-approved new molecular entities eventually required label changes regarding dosing after approval, indicating persistent challenges in establishing optimal dosing regimens [30].

The Linear No-Threshold Model: Foundations and Controversies

Historical Development and Scientific Basis

The LNT model has its origins in early 20th-century radiation biology. In 1927, Hermann Muller demonstrated that radiation could cause genetic mutations, for which he received a Nobel Prize [31]. In his Nobel lecture, Muller asserted that mutation frequency was "directly and simply proportional to the dose of irradiation applied" and that there was "no threshold dose" [31]. This concept gained further support from studies by Gilbert N. Lewis and Alex Olson, who proposed that genomic mutation occurred proportionally to radiation dose [31].

The model was solidified in regulatory frameworks through a series of developments from the 1950s to the 1970s. In 1954, the National Council on Radiation Protection (NCRP) introduced the concept of maximum permissible dose, replacing the earlier tolerance dose concept [33]. The Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) subsequently introduced the ALARA principle ("As Low As Reasonably Achievable") in 1972, which implicitly accepted the LNT model by suggesting that any dose, no matter how small, carries some risk [33]. This was further reinforced by the 1972 BEIR (Biological Effects of Ionizing Radiation) report, which provided cancer risk estimates based on linear extrapolation from high-dose data [33].

The LNT model serves as a conservative default in regulatory toxicology because it simplifies risk assessment, especially when data at low doses are limited or uncertain [34] [35]. Regulatory bodies such as the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission (NRC) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) employ the LNT model for establishing protective standards, operating under the precautionary principle that it is better to overestimate than underestimate potential risks [31] [35].

Ongoing Scientific Debate and Challenges

Despite its regulatory acceptance, the LNT model remains scientifically contentious. Critics argue that the model may be overly conservative, potentially leading to excessive regulatory compliance costs without commensurate public health benefits [34] [35]. The model has been challenged on several biological grounds:

- Defense Mechanisms: Opponents note that the LNT model does not fully account for the body's sophisticated defense mechanisms, including DNA repair processes and programmed cell death, which may effectively handle low-level exposures to carcinogens [31].

- Immune Stimulation: Evidence suggests that the immune system response to radiation exposure is nonlinear, with high doses being immunosuppressive while low doses may actually stimulate immune function [32]. This biphasic response contradicts the fundamental assumption of the LNT model.

- Adaptive Responses: Research has documented adaptive responses where low doses of stressors may precondition organisms to better handle subsequent higher doses [33]. The 1994 UNSCEAR report devoted significant attention to these adaptive responses to radiation in cells and organisms [33].

The fundamental challenge in resolving this debate is the epidemiological difficulty of detecting small effects at low doses against background cancer incidence [31] [35]. As noted in the search results, "roughly 4 out of 10 people will develop cancer in their lifetimes" from various causes, making it "functionally impossible" to quantify cancer risk from low-dose radiation exposure well below background levels [35]. This statistical limitation means that the LNT model's applicability at low doses remains an extrapolation rather than an observationally verified fact.

Table 1: Alternative Dose-Response Models in Toxicological Risk Assessment

| Model Type | Fundamental Premise | Regulatory Application | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear No-Threshold (LNT) | Risk increases linearly from zero dose; no safe threshold exists | Default model for radiation and carcinogen risk assessment | May overestimate risk at low doses; ignores biological defense mechanisms |

| Threshold | No significant risk below a certain dose threshold | Standard for most toxicological endpoints (e.g., organ toxicity) | Threshold determination has uncertainty; may not protect hypersensitive subpopulations |

| Hormesis | Low doses are beneficial or protective; high doses are harmful | Not routinely used in regulatory settings | Difficult to distinguish from background variation; reproducibility concerns |

Threshold Doses in Preclinical Drug Development

Defining Threshold Concepts in Pharmacology

In preclinical pharmacology, threshold doses represent critical transition points in dose-response relationships. The No Observable Adverse Effect Level (NOAEL) is a fundamental threshold concept, defined as the highest dose at which no statistically or biologically significant adverse effects are observed [36]. Closely related is the Human Equivalent Dose (HED), derived from animal NOAELs and used to establish the Maximum Safe Starting Dose for first-in-human (FIH) clinical trials [36]. These thresholds are essential for determining the therapeutic window - the range between the minimally effective dose and the dose where unacceptable adverse effects occur [36].

The determination of these threshold values is complicated by the fact that pharmacokinetic parameters often change disproportionately across dose ranges. As noted in the search results, "As dose levels increase many of the key ADME processes can become saturated, significantly changing the exposure profile at higher dose levels in different ways" [36]. This nonlinearity means that exposure parameters (e.g., AUC, Cmax) determined at high doses used in toxicology studies may not accurately predict exposure at therapeutically relevant doses, necessitating dedicated pharmacokinetic studies in the pharmacologically active dose range [36].

Methodological Framework for Dose-Finding

A structured approach to dose-finding is critical for successful drug development. Recent initiatives have introduced formal dose-finding frameworks to organize knowledge and facilitate collaboration in multidisciplinary development teams [30]. These frameworks consist of two main components: (1) knowledge collection to establish common understanding of constraints and assumptions, and (2) strategy building to translate knowledge into a development path [30].

These frameworks emphasize an iterative process that spans all phases of drug development, starting before preclinical studies and continuing through confirmatory trials [30]. The approach helps teams address the challenge that "finding the right treatment at the right dose for the right patient at the right time remains difficult due to a multitude of practical, scientific, and/or financial constraints" [30]. Implementation of such frameworks across more than 25 projects has demonstrated benefits including clearer differentiation of dose-finding strategies for different indications and identification of opportunities to generate additional biomarker data to strengthen exposure-response assessment [30].

Experimental Design for Dose-Response Studies

Preclinical Dose-Response Experimentation

Well-designed preclinical dose-response studies are essential for characterizing a compound's pharmacological profile and informing clinical trial design. In tumour-control assays, a common preclinical model, "the response of individual tumours to treatment is observed until a pre-defined follow-up time is reached" [37]. The fraction of controlled tumours at each dose level forms the tumour-control fraction (TCF), which follows a sigmoidal dose-response relationship that can be modeled using logistic regression [37].

A key consideration in designing these experiments is sample size calculation, which must account for the nonlinear nature of dose-response relationships. Monte-Carlo-based approaches have been developed to estimate the required number of animals in two-arm tumour-control assays comparing dose-modifying factors between control and experimental arms [37]. These methods are particularly important for detecting effects in heterogeneous tumour models with varying radiosensitivity [37].

The selection of appropriate dose levels and spacing is another critical design element. As noted in recent methodological research, "A dose-response design requires more thought relative to a simpler study design, needing parameters for the number of doses, the dose values, and the sample size per dose" [38]. Statistical power calculations guide these parameter choices to ensure reliable comparison of dose-response curves between experimental conditions [38].

Advanced Computational Approaches

Modern computational methods are enhancing dose-response modeling capabilities. Multi-output Gaussian Process (MOGP) models represent an advanced approach that simultaneously predicts responses at all tested doses, enabling assessment of any dose-response summary statistic [39]. Unlike traditional methods that require selection of summary metrics (e.g., ICâ‚…â‚€, AUC), MOGP models describe the relationship between genomic features, chemical properties, and responses across the entire dose range [39].

These models also facilitate biomarker discovery through feature importance analysis using methods like Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence to identify genomic features most relevant to dose-response relationships [39]. For example, this approach identified EZH2 gene mutation as a novel biomarker of BRAF inhibitor response that had not been detected through conventional ANOVA analysis [39].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Dose-Response Studies

| Reagent/Tool Category | Specific Examples | Research Application | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Model Systems | Patient-derived xenografts, genetically engineered models, heterogeneous tumour cohorts [37] | Tumour-control assays, efficacy and potency assessment | Model selection affects translational relevance; heterogeneity requires larger sample sizes |

| Computational Tools | Multi-output Gaussian Process (MOGP) models [39], Monte Carlo simulation [37] | Dose-response prediction, sample size calculation, biomarker discovery | Requires specialized statistical expertise; validated against experimental standards |

| Biomarker Assays | Genomic variation analysis, copy number alteration assessment, DNA methylation profiling [39] | Mechanism of action studies, response biomarker identification | Multi-omics integration improves predictive accuracy; requires appropriate normalization |

Decision Framework for Model Selection

Criteria for Model Application

Selecting an appropriate dose-response model requires consideration of multiple factors. The mechanism of action of the stressor or therapeutic agent should guide model selection. For mutagenic agents that directly damage DNA, the LNT model may be more appropriate, while for agents with receptor-mediated effects, threshold models are generally more applicable [32]. The biological context is equally important, considering factors such as tissue type, repair capacity, and exposure duration [33].

The intended application and regulatory requirements also influence model selection. Risk assessment for public health protection often employs more conservative models like LNT, while therapeutic optimization may focus on accurately characterizing the therapeutic window using threshold concepts [36]. Practical constraints, including the feasibility of collecting sufficient data at low doses to distinguish between models, often dictate the default to LNT as a precautionary approach [34] [35].

Integrated Risk-Benefit Assessment

A comprehensive approach to dose-response interpretation must integrate both risks and benefits. The LNT model focuses exclusively on risk, while threshold and hormesis models incorporate potential benefits at low doses [32]. In drug development, this integration is formalized through the benefit-risk assessment, which quantifies the therapeutic window based on relative exposure-time profiles for both pharmacodynamic and adverse effects [36].

The dose-finding framework mentioned in the search results provides a structure for this integrated assessment, helping teams "establish a common ground of knowns and unknowns about a drug, the disease and target population(s) and the wider development context, and for mapping this knowledge onto viable strategies" [30]. This approach emphasizes starting early in development and revising often as new knowledge is acquired [30].

Decision Framework for Dose-Response Model Selection

The debate between the linear no-threshold model and threshold models represents more than a theoretical scientific dispute—it embodies fundamental differences in approach to risk characterization and therapeutic optimization. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the strengths and limitations of each model is essential for appropriate study design and data interpretation.

The LNT model provides a conservative, precautionary approach valuable for public health protection, particularly when data are limited [34] [31]. However, its application may lead to overly stringent standards that do not account for biological defense mechanisms or potential benefits at low doses [31] [32]. Threshold models often better reflect biological reality for many endpoints but require more extensive data to establish no-effect levels [36].

Moving forward, the field will benefit from continued refinement of experimental frameworks that generate high-quality dose-response data across the entire dose spectrum [30] [38]. Additionally, the development of sophisticated computational approaches like multi-output Gaussian Process models will enhance our ability to extract maximum information from limited data [39]. Ultimately, the appropriate model depends on the specific biological context, mechanism of action, and intended application—requiring researchers to exercise informed judgment rather than relying on one-size-fits-all approaches.

As dose-response modeling continues to evolve, the integration of advanced computational methods with rigorous experimental design promises to refine our understanding of threshold phenomena and improve the efficiency of drug development. This progression will better equip researchers to establish therapeutic windows that maximize efficacy while minimizing risk, ultimately benefiting both drug developers and patients.

From Data to Decisions: Practical Methods for Curve Generation, Modeling, and Analysis

In preclinical research, a dose-response curve is a critical tool for quantifying the relationship between the dose or concentration of a substance (e.g., a drug) and the magnitude of the effect it produces in a biological system. Establishing this relationship is fundamental to drug development, as it helps determine crucial parameters like a drug's potency and efficacy. In modern oncology drug development, for example, the focus has shifted from simply finding the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) for cytotoxic drugs to defining the optimal biological dose (OBD) for targeted therapies, which often offers a better efficacy-tolerability balance [7]. Accurately interpreting these curves allows researchers to make informed predictions about therapeutic potential and safety profiles before a candidate drug progresses to clinical trials. This guide provides a detailed protocol for generating, modeling, and interpreting dose-response data, framed within the context of a rigorous preclinical research workflow.

Experimental Design and Data Collection

Key Research Reagents and Materials

A successful dose-response experiment relies on high-quality, well-characterized reagents and a robust experimental design. The table below summarizes essential materials and their functions.

Table 1: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for Dose-Response Experiments

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| Test Compound | The investigational drug or substance. A pure, stable compound with a known molecular weight and solubility profile is essential. |

| Solvent/Vehicle | A solvent (e.g., DMSO, saline) to dissolve the compound. It must not exert any biological effects on its own at the concentrations used. |

| Biological System | The in vitro model (e.g., cell lines, primary cells, enzymes) or in vivo model (e.g., animal models) used to measure the response. |

| Assay Reagents | Kits and chemicals required to quantify the biological effect (e.g., cell viability assays like MTT, ATP-based luminescence, or target engagement assays). |

| Positive/Negative Controls | Compounds with known activity (positive control) and vehicle-only treatments (negative control) to validate the assay's performance. |

Step-by-Step Experimental Protocol

Compound Preparation:

- Prepare a high-concentration stock solution of the test compound in a suitable vehicle, ensuring complete dissolution.

- Serially dilute the stock to create a range of concentrations (typically 8-12 doses) covering several orders of magnitude (e.g., from 1 nM to 100 µM). Using a logarithmic scale (e.g., half-log or 1:3 serial dilutions) is standard practice.

Treatment and Incubation:

- Apply the compound dilutions to your biological system (e.g., plate cells in a 96-well plate and add compound). Each concentration should be tested in multiple replicates (a minimum of 3 is standard) to account for biological and technical variability.

- Include vehicle-only controls (0% effect) and a control for maximum effect (e.g., a well-characterized inhibitor for 100% inhibition, or a cell lysate for 0% viability).

- Incubate the system for a predetermined time that is physiologically relevant.

Response Measurement:

- After incubation, quantify the biological effect using an appropriate assay. For cell viability, this could be a colorimetric or luminescent assay.

- Record the raw output data (e.g., absorbance, luminescence, fluorescence) for each well.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key stages of a dose-response experiment.

Figure 1: Dose-Response Experimental Workflow

Data Analysis and Curve Fitting

Data Normalization and Preparation

Before fitting a curve, raw data must be normalized to a percentage of effect relative to the controls.

- For Inhibitory Responses (e.g., cell viability):

Normalized Response (%) = 100 × [1 - (Raw_Data - Min_Effect) / (Max_Effect - Min_Effect)]WhereMax_Effectis the average signal from the vehicle control (0% inhibition) andMin_Effectis the average signal from the maximum inhibition control (100% inhibition).

Curve Fitting with Parametric Models