In Vivo Microdialysis for Neurotransmitter Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in vivo microdialysis, a minimally invasive sampling technique pivotal for measuring unbound neurotransmitter concentrations in the brain extracellular fluid of awake, freely behaving...

In Vivo Microdialysis for Neurotransmitter Analysis: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers and Drug Developers

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of in vivo microdialysis, a minimally invasive sampling technique pivotal for measuring unbound neurotransmitter concentrations in the brain extracellular fluid of awake, freely behaving animals. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles and history of the technique, detailed methodological setup and calibration, advanced applications in pharmacokinetics and disease modeling, and troubleshooting for common experimental challenges. By integrating recent advances in analytical chemistry such as UHPLC and LC-MS/MS, and discussing validation against other methods, this guide serves as an essential resource for designing robust microdialysis studies to accelerate neuroscience research and central nervous system drug discovery.

Understanding In Vivo Microdialysis: Principles and Historical Context

Microdialysis is a minimally invasive sampling technique that enables the continuous monitoring of chemical events in the extracellular fluid of living tissues [1] [2]. By mimicking the passive function of a blood capillary, this method allows researchers to obtain a representative sample of the extracellular milieu without removing fluid from the tissue [2]. In neuroscience research, microdialysis has become an indispensable tool for measuring dynamic changes in neurotransmitter release and metabolism in specific brain regions of awake, freely-moving animals, providing critical insights into brain function and the mechanisms of drug action [3] [4].

The fundamental principle governing microdialysis is passive diffusion driven by concentration gradients across a semi-permeable membrane [2]. This technique permits both sampling of endogenous substances and local administration of exogenous compounds, making it uniquely versatile for pharmacological studies [4]. When applied to neurotransmitter monitoring, microdialysis offers the distinct advantage of measuring multiple neurochemicals simultaneously with high sensitivity, often in the picomolar range [3].

Core Principles and Technical Parameters

The Microdialysis Probe: Design and Function

The microdialysis probe serves as an artificial blood vessel, with its core component being a semi-permeable membrane positioned at the tip [1] [4]. The most common design employs a concentric tube structure where perfusion fluid enters through an inner tube, flows to its distal end, reverses direction into the space between the inner tube and outer dialysis membrane, and finally exits through the outlet tube for collection [1] [4]. It is within this space between the tubes that the essential "dialysis" process occurs – the diffusion of molecules between the extracellular fluid and the perfusion fluid [1].

The molecular weight cutoff of the membrane, typically ranging from 20-100 kilodaltons (kDa), determines the size range of molecules that can be sampled [2] [3]. Lower molecular weight cutoffs purify the sample by excluding large molecules, while higher cutoffs enable recovery of peptides and small proteins [4]. The membrane length also significantly influences recovery, with longer membranes generally providing better recovery, though this must be balanced against the size of the brain structure being studied [4].

Critical Factors Affecting Analytic Recovery

The efficiency of analyte recovery in microdialysis – referred to as relative recovery – depends on several interconnected factors [3]. Understanding and optimizing these parameters is essential for obtaining meaningful experimental data:

- Flow Rate: Lower flow rates (e.g., 0.1-1 µL/min) yield more concentrated dialysate by allowing more time for diffusion equilibrium, while higher flow rates (1-5 µL/min) remove more molecules per unit time but produce more dilute samples [2] [4].

- Membrane Surface Area: Larger surface areas, achieved through increased membrane length or diameter, enhance recovery by providing greater exchange area [3].

- Diffusion Characteristics: The diffusion coefficient of the target analyte and its penetration distance through the tissue to the probe membrane significantly influence recovery rates [3].

- Perfusate Composition: The perfusion fluid should ideally match the ionic composition of the extracellular fluid, commonly using artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) or Ringer's solution to minimize tissue disturbance [2] [3].

Table 1: Key Technical Parameters in Microdialysis Experiment Design

| Parameter | Typical Range | Impact on Recovery | Application Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flow Rate | 0.1 - 5 µL/min | Inverse relationship with concentration; lower flow = higher concentration | Low flow for concentrated samples; high flow for maximal molecule collection per time unit [2] [4] |

| Membrane Length | 1 - 4 mm | Positive relationship; longer membrane = higher recovery | Limited by size of target brain structure [4] |

| Molecular Weight Cutoff | 20 - 100 kDa | Determines size range of recovered molecules | Low MWCO for small molecules only; high MWCO for peptides/proteins [3] [4] |

| Membrane Material | Various polymers | Affects biocompatibility and fouling potential | CMA, D-I-6-02, and other commercial probes available [5] [6] |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Measuring Monoaminergic Neurotransmitters Following Pharmacological Challenge

This protocol outlines the steps for measuring extracellular levels of monoaminergic neurotransmitters (dopamine, DA; norepinephrine, NE; serotonin, 5-HT) and their metabolites in response to drug administration in awake, freely moving mice [6].

Materials and Surgical Preparation

- Animals: Mice (e.g., C57BL/6J)

- Anesthetic: Pentobarbital (Nembutal, 50 mg/kg) or equivalent

- Stereotaxic apparatus equipped with mouse adapter (e.g., David Kopf)

- Dialysis probe: D-I-6-02 with 50,000 Da cut-off (Eicom) or equivalent concentric design probe

- Dental cement for probe fixation

- Guide cannula (for chronic implantation)

Surgical Procedure:

- Anesthetize the mouse and secure it in the stereotaxic apparatus.

- Implant a guide cannula above the target brain region using stereotaxic coordinates from a mouse brain atlas [6].

- Secure the guide cannula to the skull using dental cement.

- Allow animals to recover individually for 2-3 days before experimentation [6].

Microdialysis Sampling and HPLC Analysis

- Perfusion solution: Ringer's solution (147 mM Na+, 4 mM K+, 2.3 mM Ca+, 155.6 mM Cl−) [6]

- Syringe pump (e.g., ESP-64, Eicom) for precise flow control

- Auto injector (e.g., EAS-2, Eicom) for automated sample handling

- HPLC system with electrochemical detection (e.g., HTEC-500, Eicom)

Experimental Procedure:

- Gently insert the microdialysis probe through the guide cannula into the target brain region.

- Place the mouse in a testing cage with free access to food and water.

- Perfuse the probe with Ringer's solution at 2.0 μL/min using a syringe pump [6].

- Collect dialysate samples automatically every 25 minutes using an auto injector [6].

- After collecting at least four baseline samples, administer either saline (control) or drug (e.g., 10 mg/kg BUP) intraperitoneally.

- Continue collecting at least six additional post-administration samples.

- Immediately inject each dialysate sample into the HPLC system for analysis.

HPLC-ECD Conditions [6]:

- Column: SC-50DS (Eicom)

- Mobile phase: 83% 0.1 M acetic acid-citric acid buffer (pH 3.5), 17% methanol, 190 mg/L octanesulfonic acid, 5 mg/L Naâ‚‚EDTA

- Flow rate: 0.23 mL/min

- Detection: Electrochemical detector with graphite electrode at +700 mV vs. Ag/AgCl reference electrode

Histological Verification

- After completing microdialysis measurement, perfuse eosin solution through the probe to mark its placement.

- Euthanize the mouse via pentobarbital overdose.

- Remove and fix the brain in 10% formaldehyde neutral buffer solution.

- Verify probe placement histologically through sectioning and microscopy [6].

Protocol: Integrated Neurotransmitter Analysis with LC-MS/MS

This advanced protocol utilizes liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for deep coverage of the brain extracellular metabolome, enabling identification of hundreds of compounds in microliter sample volumes [5].

Sample Collection and Preparation

- Animals: Male Sprague-Dawley rats (~75 days old, 340-375 g)

- Microdialysis probes: CMA 12 Elite with 4 mm membrane and 20,000 Da molecular weight cutoff [5]

- Perfusate: Artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF: 145 mM NaCl, 2.68 mM KCl, 1.40 mM CaClâ‚‚, 1.01 mM MgSOâ‚„, 1.55 mM Naâ‚‚HPOâ‚„, 0.45 mM NaHâ‚‚POâ‚„, 0.25 mM ascorbic acid) [5]

- Flow rate: 1 μL/min during 12-hour collection from striatum [5]

Sample Preparation Options:

- Underivatized Analysis: Pool dialysate samples from multiple animals. For 10-fold concentration, transfer 750 μL aliquots to tapered glass vials, dry in a vacuum centrifuge, and reconstitute with 75 μL of appropriate solvent (9:1 water:methanol for RPLC; 85:15 acetonitrile:water for HILIC) [5].

- Chemical Derivatization: To enhance detection of polar neurotransmitters, derivatize equal aliquots of dialysate with light and heavy (13C6) benzoyl chloride separately to create detectable mass pairs for improved identification [5].

LC-MS/MS Analysis Conditions

- LC System: Thermo Fisher Scientific Vanquish Horizon LC

- Mass Spectrometer: Orbitrap ID-X mass spectrometer

- LC Columns:

- Reversed-phase (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.8 μm HSST3)

- HILIC (2.1 × 100 mm, 1.7 μm BEH Amide)

- Mass Spectrometer Settings [5]:

- Sheath gas: 40; Aux gas: 10; Sweep gas: 1

- Ion transfer tube temperature: 325°C; Vaporizer temperature: 300°C

- Orbitrap resolution: 120,000 (MS1), 60,000 (MS2)

- Scan range: 70-800 m/z

- Spray voltage: ±3200 V (positive/negative mode)

Data Processing and Compound Identification

- Software: MetIDTracker for untargeted MS/MS data

- Spectral Libraries: NIST20, Massbank of North America (MONA), MS-Dial LipidBlast

- Identification Confidence: Match experimental MS/MS spectra to reference libraries with appropriate scoring thresholds [5]

This approach has been shown to enable identification of 479 unique compounds from rat striatal dialysate, with approximately 60% detectable in 5 μL samples without preconcentration [5]. Benzoyl chloride derivatization further expands detection to 872 non-degenerate features, including most small molecule neurotransmitters and dopamine metabolites [5].

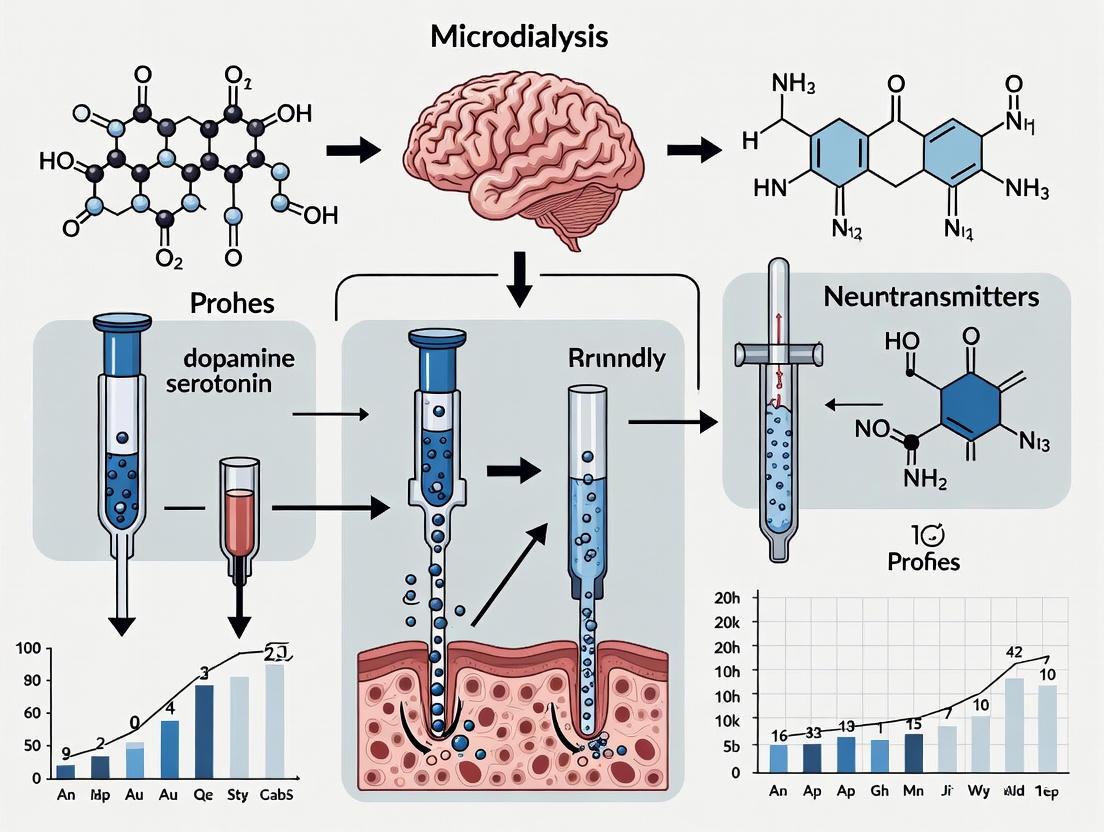

Visualization of Microdialysis Workflows

Microdialysis Principle and Probe Design

Integrated Experimental Workflow

Analytical Approaches and Data Interpretation

Quantitative Analysis of Neurotransmitters

Microdialysis sampling requires careful calibration to relate measured dialysate concentrations to true extracellular concentrations. The relative recovery – defined as the ratio of analyte concentration in the dialysate to that in the extracellular fluid – must be determined for accurate quantification [3]. The zero-net-flux method is often employed for this purpose, where the probe is perfused with different concentrations of the analyte of interest, and the tissue concentration is determined as the point where inflow and outflow concentrations are equal [2].

Table 2: Analytical Methods for Neurotransmitter Detection in Microdialysate

| Analytical Method | Detection Limit | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HPLC-ECD | Low picomole to femtomole | Monoamines (DA, NE, 5-HT) and metabolites [6] | High sensitivity for electroactive compounds; Relatively low cost [6] | Limited to electroactive compounds; Lower compound identification confidence |

| LC-MS/MS | Low femtomole to attomole | Targeted and untargeted metabolomics; Multiple neurotransmitter classes [5] | High specificity and sensitivity; Broad compound coverage; Structural confirmation via MS/MS [5] | Higher instrument cost; Complex sample preparation; Matrix effects |

| Enzymatic Assays | Picomole | Energy metabolites (glucose, lactate, glycerol) | High specificity for target metabolites; Commercially available kits | Typically limited to single metabolites per assay |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Materials for Microdialysis Experiments

| Item | Specification | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Microdialysis Probes | Concentric design; 1-4 mm membrane length; 20-100 kDa MWCO [5] [6] | Core sampling device implanted in target tissue |

| Perfusion Fluids | Artificial CSF or Ringer's solution [6] [3] | Physiological solution mimicking extracellular fluid composition |

| Syringe Pump | Low flow rate capability (0.1-5 µL/min); High precision [6] | Controls perfusion flow rate through the probe |

| Microvials | Low protein binding; 100-500 µL capacity | Collection of dialysate samples |

| Autosampler | Compatible with microvials; Temperature-controlled [7] | Automated sample handling and injection for HPLC |

| HPLC System | Binary or quaternary pump; Column oven; Autosampler [6] | Separation of analytes prior to detection |

| ECD Detector | Glassy carbon working electrode; Ag/AgCl reference; ±2000 mV range [6] | Sensitive detection of electroactive neurotransmitters |

| Mass Spectrometer | High resolution (Orbitrap, Q-TOF); Tandem MS capability [5] | Identification and quantification of multiple neurochemicals |

| Stereotaxic Apparatus | Species-specific adapters; Digital coordinate readout | Precise probe implantation in target brain regions |

| BMT-145027 | BMT-145027, CAS:2018282-44-3, MF:C23H14ClF3N4, MW:438.84 | Chemical Reagent |

| Notum-IN-1 | [1-(3,4-Dichlorophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]methanol | CAS 338419-11-7. This high-purity [1-(3,4-dichlorophenyl)-1H-1,2,3-triazol-4-yl]methanol is a key triazole building block for antifungal and antimicrobial research. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

Applications in Neuropharmacology and Drug Development

Microdialysis provides critical insights for CNS drug development by enabling direct measurement of unbound drug concentrations in the brain extracellular fluid, which more accurately reflects pharmacologically active concentrations than total tissue levels or cerebrospinal fluid measurements [8]. When combined with blood microdialysis in the same animal, researchers can directly determine the unbound partition coefficient (Kp,uu), a key parameter for evaluating brain penetration [8].

In non-human primate studies, brain microdialysis has demonstrated particular translational value due to similarities in blood-brain barrier transporter expression between primates and humans [8]. For example, studies with carbamazepine – a non-P-gp substrate – have validated the technique, showing brain extracellular fluid concentrations reaching approximately 80% of free plasma concentrations, consistent with passive diffusion across the blood-brain barrier [8].

Beyond pharmacokinetic applications, microdialysis enables real-time monitoring of neurotransmitter responses to drug administration, facilitating comprehensive pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK-PD) relationships for CNS-active compounds [4] [8]. This capability is particularly valuable for understanding the mechanisms of drugs for psychiatric and neurological disorders, where neurotransmitter dynamics are often central to therapeutic effects.

The accurate measurement of neurotransmitter dynamics in the awake, behaving brain remains a central challenge in neuroscience and drug development. Microdialysis has evolved to meet this challenge, transforming from a rudimentary sampling concept into a sophisticated, minimally-invasive technique that enables continuous measurement of unbound analyte concentrations in the extracellular fluid of virtually any tissue [9]. This evolution from early "dialytrodes" to modern hollow-fiber membranes represents a critical advancement in our ability to monitor neurochemical processes in vivo [10]. The technique's unique capability to sample endogenous neurotransmitters, hormones, and metabolites directly from the brain's extracellular space, while simultaneously permitting local drug delivery, has established it as a gold standard in neurochemical monitoring [11] [9]. This application note traces the historical development of microdialysis, details current protocols for neurotransmitter monitoring, and provides resources for implementing this powerful technique in neuroscience research and drug development programs.

Historical Development: From Dialytrodes to Hollow Fibers

The conceptual foundation of microdialysis was laid in the early 1960s with the use of push-pull cannulas and implanted dialysis sacs to study tissue biochemistry [12] [9]. These early approaches faced significant limitations, including limited sample number and poor temporal resolution. A critical advancement came in 1972 with the development of the first "dialytrode" by Delgado et al., which featured a slowly perfused dialysis bag that carried samples to an accessible site [12]. Ungerstedt and Pycock introduced the revolutionary "hollow fiber" concept in 1974, replacing dialysis bags with tubular semipermeable membranes approximately 200-300 μm in diameter [9]. This innovation dramatically improved sampling efficiency and formed the basis for the modern microdialysis probe.

The subsequent refinement of the needle probe design, consisting of a shaft with a hollow fiber at its tip that could be inserted into tissue via a guide cannula, established microdialysis as a practical and reliable neuroscientific tool [10]. The 1980s witnessed the coupling of microdialysis with high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) and electrochemical detection, enabling precise quantification of monoamines and other neurotransmitters [11]. This period also saw the technique's expansion beyond neurotransmitter monitoring to include energy substrates, drugs, and metabolites, solidifying its role in neuroscience and clinical research [12] [10].

Table 1: Evolution of Microdialysis Technology

| Time Period | Key Development | Primary Innovation | Significant Advancement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early 1960s | Dialysis Sacs & Push-Pull Cannulas [12] [9] | First implantation into tissues to study biochemistry | Direct access to brain extracellular fluid |

| 1972 | Dialytrode [12] | Perfused dialysis bag with carried sample | Improved sample collection and accessibility |

| 1974 | Hollow Fiber [9] | Tubular semipermeable membrane (~200-300 μm diameter) | Dramatically improved sampling efficiency and reliability |

| 1980s | HPLC & Electrochemical Detection Coupling [11] | Analytical chemistry integration | Precise quantification of monoamines and neurotransmitters |

| 1990s-Present | Clinical Applications & Miniaturization [10] [11] | Human tissue monitoring & improved probe designs | Expanded to clinical settings, higher temporal and spatial resolution |

The following diagram illustrates the key developmental milestones in microdialysis technology:

Principles and Methodological Framework

Core Principles of Microdialysis

Microdialysis operates on the principle of passive diffusion across a semipermeable membrane, enabling the exchange of small molecules between the extracellular fluid and a perfused physiological solution [11] [9]. A typical microdialysis probe consists of a double-lumen catheter with a semipermeable membrane at its tip, which is implanted into the brain region of interest and perfused with an isotonic solution at controlled flow rates (typically 0.1-5 μL/min) [11]. The membrane's molecular weight cut-off (usually 6-100 kDa) determines which molecules can diffuse through, excluding larger proteins and macromolecules [9]. This molecular size exclusion allows microdialysis to sample specifically the free, unbound fraction of neurotransmitters and drugs that represents the pharmacologically active concentration [13].

The recovery of analytes – defined as the ratio of analyte concentration in the dialysate to that in the extracellular fluid – is a critical parameter in microdialysis methodology [9]. Recovery depends on several factors including membrane surface area, pore size, flow rate, and tissue properties [11]. Lower flow rates (<1 μL/min) typically increase relative recovery but decrease absolute recovery, necessitating careful optimization based on experimental requirements [11].

Calibration Methods

Accurate quantification of extracellular concentrations requires appropriate calibration methods to determine relative recovery [9]. The most common approaches include:

- No-Net-Flux Method: The probe is perfused with at least four different concentrations of the analyte of interest, and the point at which no net diffusion occurs represents the true extracellular concentration [9].

- Retrodialysis: Uses an internal standard added to the perfusate, assuming equal diffusion rates in both directions to estimate in vivo recovery [11] [9]. This method is particularly useful for exogenous compounds.

- Low-Flow-Rate Method: Extraction ratios are measured at different flow rates and extrapolated to zero flow, where complete equilibrium theoretically occurs [9].

- Dynamic No-Net-Flux Method: An extension of the no-net-flux method that allows determination of recovery over time, making it suitable for studies evaluating responses to drug challenges [9].

Table 2: Comparison of Microdialysis Calibration Methods

| Calibration Method | Principle | Best Suited Applications | Key Advantages | Important Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Net-Flux [9] | Perfusion with varying analyte concentrations to find no-net-flux point | Endogenous compounds under steady-state conditions | Direct measurement of extracellular concentration | Requires steady-state conditions; time-consuming |

| Retrodialysis [11] [9] | Measurement of analyte disappearance from perfusate | Exogenous compounds; clinical settings | Simple implementation; suitable for drugs | Not applicable to endogenous compounds |

| Low-Flow-Rate [9] | Extrapolation from multiple flow rates to zero flow | Both endogenous and exogenous compounds | No addition of analyte required | Long calibration times; impractical for some applications |

| Dynamic No-Net-Flux [9] | Multiple subjects with single concentrations combined for regression | Endogenous compound response to challenges | Enables recovery determination over time | Requires multiple subjects/animals |

Experimental Protocols: Measuring Neurotransmitters in Awake Non-Human Primates

The following protocol describes the implementation of brain microdialysis in awake rhesus macaques to compare cortical neurotransmitter concentrations across different cognitive states, based on recently published methodology [14]. This approach enables simultaneous measurement of multiple neurotransmitters, including GABA, glutamate, norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and choline, during performance of behavioral tasks.

Materials and Equipment

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Equipment

| Category | Specific Item | Function/Application |

|---|---|---|

| Surgical Components | Stereotactic frame, guide cannulas, removable insets | Precise probe implantation and stabilization |

| Microdialysis Probes | Concentric design hollow fiber probes, molecular weight cut-off 20-100 kDa | Sampling of neurotransmitters from extracellular fluid |

| Perfusion System | Micronfusion pump, microtubing, physiological perfusion solution (artificial CSF) | Controlled delivery of perfusion fluid to probe |

| Sample Collection | Microvials, refrigerated fraction collector | Maintenance of sample integrity post-collection |

| Analytical Instrumentation | UPLC-ESI-MS system, analytical column, mobile phases | Separation and quantification of neurotransmitters |

| Calibration Standards | GABA, glutamate, monoamines, choline reference standards | Method calibration and quantification |

Procedure

Guide Cannula Implantation: Under aseptic conditions and general anesthesia, implant guide cannulas with removable insets positioned above the target brain region (e.g., visual middle temporal area MT) using stereotactic coordinates. Secure the assembly within a standard recording chamber.

Postoperative Recovery: Allow a minimum of 2 weeks for surgical recovery before commencing experiments. Monitor animal health and wound healing throughout this period.

Probe Insertion and Equilibration: On experimental days, carefully replace the guide inset with a microdialysis probe, ensuring the membrane extends to the target depth. Begin perfusion with artificial cerebrospinal fluid at 1.0 μL/min and allow a minimum of 2 hours for stabilization of neurotransmitter levels post-insertion.

Sample Collection During Behavioral States: Collect dialysate samples at 20-minute intervals (<20 μL volume) during defined behavioral conditions:

- Active State: Animal engaged in cognitive tasks

- Inactive State: Animal at rest in testing apparatus Collect a minimum of 3 samples per behavioral condition to establish stable baseline measures.

Sample Processing: Immediately store collected samples at -80°C until analysis. Avoid multiple freeze-thaw cycles to maintain analyte stability.

Analytical Separation and Quantification:

- Utilize ultra-performance liquid chromatography with electrospray ionization-mass spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-MS)

- Employ a C18 reversed-phase column maintained at 35°C

- Implement a gradient elution with mobile phases consisting of 0.1% formic acid in water and 0.1% formic acid in acetonitrile

- Use multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) for maximal sensitivity and specificity

Data Analysis:

- Quantify neurotransmitter concentrations using external calibration curves

- Normalize data across subjects using protein content or probe recovery measurements

- Compare concentration variations between active and inactive states using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., paired t-tests, ANOVA with post-hoc comparisons)

- Analyze correlated concentration changes between neurotransmitter pairs

The following workflow diagram illustrates the key steps in this protocol:

Technical Notes and Optimization

- Flow Rate Considerations: Lower flow rates (0.1-0.5 μL/min) increase relative recovery but require longer collection intervals, creating a trade-off between concentration and temporal resolution [11].

- Temporal Resolution: Typical sample collection intervals range from 5-30 minutes, balancing analytical sensitivity with the ability to detect neurochemical fluctuations [13].

- Probe Placement Validation: Histological verification of probe placement is essential following experiment completion to confirm target region specificity.

- Behavioral State Transitions: Allow sufficient transition time between behavioral conditions to establish new steady-state neurotransmitter levels.

Applications in Neuroscience Research and Drug Development

Microdialysis has become an indispensable tool in neuroscience, enabling the quantification of neurotransmitters including dopamine, serotonin, glutamate, and acetylcholine in the brain during behavioral and pharmacological interventions [11]. The method allows for studies in awake, freely moving animals, facilitating correlation of neurochemical measures with specific behaviors [13]. Key application areas include:

- Neurodegenerative Disorders: Investigating neurochemical changes in Parkinson's disease, where microdialysis has revealed increased striatal tonic dopamine levels in response to subthalamic nucleus deep brain stimulation in rodent models [11].

- Neuropharmacology: Studying pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of drugs in brain tissue, including assessment of blood-brain barrier transport and local drug delivery by measuring unbound drug concentrations [11] [13].

- Neurocritical Care: Monitoring biochemical markers of ischemia, such as glutamate and lactate/pyruvate ratios, in patients with traumatic brain injury, stroke, and subarachnoid hemorrhage, enabling early detection of secondary damage and guiding therapeutic interventions [10] [11].

- Drug Development: Evaluating tissue penetration of chemotherapeutic agents in tumors and antibiotics at infection sites, providing critical data on target site pharmacokinetics that cannot be obtained through plasma monitoring alone [10] [13].

Technical Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its widespread utility, microdialysis faces several technical challenges. Probe implantation causes tissue damage, with a concentric gradient of damaged cells extending approximately 250 μm from the probe, potentially confounding data interpretation [11]. The typical probe diameter of 200-300 μm significantly exceeds the intercapillary distance in rodent brains (approximately 30 μm), resulting in blood vessel damage, blood-brain barrier compromise, and rapid inflammatory responses including gliosis [11]. These tissue reactions can reduce probe stability and impede analyte diffusion. Temporal resolution is constrained by perfusion flow rates and sample volume requirements, typically limiting measurements to 5-minute intervals or longer [11].

Future developments focus on probe miniaturization through microfabrication techniques, with silicon microdialysis probes now reaching dimensions as small as 45 by 180 μm [11]. Emerging innovations include aptamer-based biosensors for selective molecular detection, multimodal devices combining chemical sensing with stimulation and electrophysiological recording, and segmented flow techniques that improve temporal resolution to under 15 seconds [11] [13]. Retrodialysis of anti-inflammatory agents like dexamethasone has shown promise in reducing glial scarring and restoring normal neurotransmitter dynamics around the probe [11]. These advances continue to enhance the spatiotemporal resolution and expand the capabilities of microdialysis in neuroscience research.

From its origins in basic dialytrode technology to the sophisticated hollow-fiber systems in use today, microdialysis has established itself as a fundamental tool for monitoring neurochemical dynamics in vivo. The technique's unique capacity to provide continuous measurement of unbound analyte concentrations in the extracellular fluid of virtually any tissue has made it invaluable for both basic neuroscience research and drug development. When implemented using the protocols described herein, microdialysis enables comprehensive investigation of neurotransmitter systems and their complex interplay in cognitive functions and behavioral states. As the technique continues to evolve through miniaturization, improved analytical coupling, and enhanced temporal resolution, its applications in understanding brain function and developing novel therapeutics will continue to expand.

In vivo microdialysis has revolutionized neuroscience research by enabling direct sampling of unbound neurotransmitters from the interstitial fluid of specific brain regions in behaving animals [12]. This technique provides critical insights into brain function by measuring the pharmacologically active fraction of neurotransmitters that interact with receptors to modulate neural circuits and behavior [15] [16]. Unlike traditional methods that measure total tissue content, microdialysis captures the dynamic, unbound neurotransmitter concentrations that reflect moment-to-moment neuronal activity and synaptic communication [17]. This Application Note details the scientific rationale for measuring unbound neurotransmitter concentrations and provides established protocols for implementing microdialysis in neurotransmitter research.

Core Advantages of Measuring Unbound Concentrations

The measurement of unbound extracellular neurotransmitter concentrations provides distinct advantages over total tissue content measurement for understanding brain function and drug effects.

Table 1: Key Advantages of Measuring Unbound Neurotransmitter Concentrations

| Advantage | Scientific Rationale | Research Application |

|---|---|---|

| Measures Pharmacologically Active Fraction | Unbound extracellular concentration directly correlates with receptor occupancy and activation [15]. | Essential for accurate pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling and determining therapeutic drug concentrations at target sites [16]. |

| Provides High Temporal Resolution | Continuous sampling allows monitoring of neurotransmitter flux in response to stimuli or drugs with minute-to-minute resolution [17]. | Ideal for studying neurotransmitter dynamics in behaviors like learning, addiction, and in response to pharmacological challenges [12] [17]. |

| Yields Protein-Free Samples | The semi-permeable membrane excludes macromolecules, including degrading enzymes, providing stable analytes ready for analysis [15]. | Enables direct injection into analytical systems (e.g., LC-EC, LC-MS) without additional sample cleanup, reducing analyte loss [15]. |

| Maintains Physiological Integrity | No fluid removal from the tissue, enabling continuous long-term sampling with minimal physiological disruption [15]. | Critical for chronic studies of neurotransmitter regulation in awake, freely moving animals, improving translational validity [12]. |

| Enables Anatomical Specificity | Small, precisely implanted probes allow sampling from discrete brain regions (e.g., striatum, nucleus accumbens) [12]. | Facilitates investigation of neurochemical heterogeneity across brain circuits implicated in specific disorders [15]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Conventional Microdialysis in Freely Moving Rats

This protocol details the steps for measuring basal and stimulated neurotransmitter release in the rat brain.

Probe Implantation and Animal Preparation

- Probe Selection: Use a concentric cannula design (250-350 μm diameter) with a polyacrylonitrile or regenerated cellulose membrane (e.g., [15]).

- Surgical Implantation: Anesthetize the rat and stereotaxically implant a guide cannula above the target brain region (e.g., striatum). Secure the cannula to the skull with dental acrylic and jeweler's screws. Allow a 24-48 hour recovery period before experimentation.

- Probe Insertion: On the experiment day, carefully insert the microdialysis probe through the guide cannula, extending the membrane into the target region.

Perfusion and Sample Collection

- Perfusion Fluid: Use an isotonic, buffered artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). For acetylcholine measurements, include a cholinesterase inhibitor (e.g., neostigmine, 0.1 μM) in the perfusate [12].

- Flow Rate: Perfuse the probe at a slow, constant rate ( 1.0 - 2.0 μL/min ) using a high-precision syringe pump [17].

- Sample Collection: Begin collection after an initial equilibration period (typically 60-120 minutes). Collect dialysate samples into microvials at 10-30 minute intervals. Keep samples on ice or a refrigerated fraction collector to preserve analyte integrity.

Analytical Determination

- Analysis: Analyze samples promptly using a suitable analytical method. For monoamines (dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine), use Liquid Chromatography with Electrochemical Detection (LC-EC) [12] [15]. For amino acids (glutamate, GABA), use LC with fluorescence detection following derivatization.

- Quantification: Quantify neurotransmitter concentrations by comparing peak areas from dialysates against freshly prepared external standards.

Protocol 2: Quantitative Microdialysis (No-Net-Flux Method)

This method determines the true extracellular concentration (Ctrue) by accounting for variable probe recovery [12].

- Perfusate with Analytic: Following the establishment of a stable baseline, perfuse the probe with aCSF containing at least four different known concentrations of the target neurotransmitter (Cin), including zero.

- Measure Dialysate Concentration: For each perfused concentration (Cin), measure the corresponding dialysate concentration (Cout).

- Calculate Gain/Loss: Calculate the difference between Cout and Cin (i.e., Cout - Cin) for each concentration.

- Plot and Determine Ctrue: Plot (Cout - Cin) against Cintrue.

Workflow and Pathway Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful implementation of microdialysis requires specific reagents and instrumentation.

Table 2: Essential Materials for Microdialysis Experiments

| Item | Function/Description | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Concentric Microdialysis Probe | A semi-permeable hollow fiber membrane on a concentric cannula for implantation into brain tissue [15]. | Sampling from discrete brain regions like striatum or hippocampus in rodents. |

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | Isotonic, buffered perfusion solution mimicking the ionic composition of brain extracellular fluid [12]. | Standard perfusate for collecting most neurotransmitters (e.g., monoamines, amino acids). |

| High-Precision Syringe Pump | Delivers perfusate at a constant, ultra-low flow rate (0.1 - 2.0 µL/min) [17]. | Critical for maintaining consistent recovery and temporal resolution. |

| Microsampling Vials | Small-volume collection vials to hold dialysate samples, often kept chilled. | Prevents analyte degradation during collection periods. |

| Liquid Chromatography System | Analytical instrument for separating neurotransmitters in the dialysate prior to detection [15]. | Standard setup for resolving complex mixtures of neurotransmitters and metabolites. |

| Electrochemical (EC) Detector | Highly sensitive detector that measures current from oxidation/reduction of electroactive analytes [15]. | Detection of monoamines (dopamine, serotonin, norepinephrine) and their metabolites. |

| ARS-1323-alkyne | ARS-1323-alkyne, MF:C28H27ClF2N6O3, MW:569.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| MMP-9-IN-9 | MMP-9-IN-9, CAS:206549-55-5, MF:C27H33N3O5S, MW:511.64 | Chemical Reagent |

The Critical Role in Systems Pharmacology and Target Site Measurement

Systems pharmacology represents a paradigm shift from traditional, single-target drug discovery to a holistic, network-based approach. This field uses computational and experimental systems biology to understand drug action across multiple scales of biological organization, explaining both therapeutic and adverse effects [18]. A core challenge in this domain is the accurate measurement of neurotransmitters at the target site, which is critical for developing a mechanistic understanding of drug action in the context of an individual's genomic status and environmental exposure [18]. Techniques like in vivo microdialysis are therefore indispensable, providing direct, quantitative insights into neurochemical dynamics in awake, behaving organisms [14].

Core Principles of Systems Pharmacology

Network-Based Drug Action Analysis

Systems pharmacology analyses rely on constructing and interpreting biological networks. In these models:

- Nodes represent entities such as drugs, proteins, genes, or diseases [18].

- Edges represent the connections between them, which can be defined by protein-protein interactions, drug-target binding, or transcriptional regulation [18].

- This framework allows researchers to transcend multiple scales of organization, from atomic-level drug-target interactions to organismal-level phenotypes, thereby avoiding the "black-box" assumptions of older models [18].

The Imperative for Direct Target Site Measurement

The theoretical power of network models must be grounded with empirical data. Direct measurement of neurotransmitter concentrations is crucial because:

- It provides quantitative, temporal data on neurotransmitter release, which is hypothesized to be a strong indicator of a drug's addictive liability and potential for abuse [19].

- It enables the development and validation of kinetic models of drug action, such as those used in neurotransmitter PET (ntPET) analysis, which characterizes the temporal profile of neurotransmitter release [19].

- Integrating these precise measurements with network models allows for the development of predictive models of therapeutic efficacy and adverse event risk [18].

Application Notes: Experimental Protocols for In Vivo Neurotransmitter Measurement

Protocol: Brain Microdialysis in Awake Non-Human Primates

This protocol details a method for comparing concentrations of cortical neurotransmitters between different cognitive states [14].

I. Surgical Implantation and Guide Cannulation

- Implant semi-chronic guide cannulas stereotaxically targeting the brain region of interest (e.g., the visual middle temporal area (MT)).

- Integrate the guides with a standard recording chamber, allowing flexible access to diverse brain regions, including areas deep within the sulcus.

- Ensure all procedures adhere to institutional animal care and use committee guidelines.

II. Microdialysis Probe Insertion and Sampling

- On the experimental day, insert a microdialysis probe through the guide cannula.

- Perfuse the probe with an artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) solution at a low flow rate (e.g., 1-2 µL/min).

- Collect dialysate samples at defined intervals (e.g., every 10-20 minutes) during distinct behavioral states, such as 'active' (engaged in a cognitive task) and 'inactive' (resting) conditions.

- Maintain a cold chain for samples prior to analysis.

III. Neurochemical Analysis via UPLC-ESI-MS

- Analyze the dialysate samples using Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography with Electrospray Ionization-Mass Spectrometry (UPLC-ESI-MS).

- This method allows for the reliable concentration measurement of a broad spectrum of neurotransmitters from small sample volumes (<20 µl).

- Key analytes include: GABA, glutamate, norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and choline [14].

IV. Data Analysis and Interpretation

- Calculate absolute concentrations of neurotransmitters by comparing sample chromatograms to standard curves.

- Compare mean concentration levels between behavioral states using appropriate statistical tests (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA).

- Perform correlation analysis on neurotransmitter concentration changes to investigate the complex interplay between different neurochemical systems [14].

Protocol: Estimating Neurotransmitter Kinetics with ntPET

This protocol describes a neuroimaging approach to estimate the kinetics of stimulus-induced neurotransmitter release in humans [19].

I. PET Scanning Protocol

- Administer a radio-labeled receptor ligand tracer intravenously.

- Conduct two dynamic PET scans on the same subject: one during a resting state (constant neurotransmitter level) and another during an activation state (time-varying neurotransmitter level induced by a pharmacological or cognitive challenge).

- Acquire data over a period sufficient to capture tracer uptake and retention (e.g., 60-90 minutes).

II. Tracer Input Function (TIF) Determination

- Arterial (ART) Method (Gold Standard): Obtain arterial blood samples throughout the scan. Process the samples to measure the concentration of the unmetabolized tracer in plasma to derive the TIF directly [19].

- Reference (REF) Method (Practical Alternative): Derive the TIF from PET data acquired in a reference region that has negligible receptor density. This avoids the need for arterial cannulation [19].

III. Kinetic Modeling with ntPET

- Fit the PET data from both the rest and activation scans simultaneously using the ntPET model.

- The model is an extension of the two-tissue compartment model and includes competition between the tracer and endogenous neurotransmitter for receptor sites.

- Concurrently estimate two sets of parameters:

- ΘTR: Parameters describing the uptake and retention of the tracer.

- ΘNT: Parameters describing the temporal profile (timing and magnitude) of neurotransmitter release in the activation condition [19].

Data Presentation and Quantitative Analysis

The following tables summarize key quantitative findings and methodological comparisons from the featured research.

Table 1: Neurotransmitter Concentration Changes Measured by Microdialysis in Awake Behaving Primates

| Neurotransmitter | Role in Brain Function | Observation in Active vs. Inactive States | Analysis Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| GABA | Primary inhibitory neurotransmitter | Subtle concentration variations observed [14] | UPLC-ESI-MS |

| Glutamate | Primary excitatory neurotransmitter | Subtle concentration variations observed [14] | UPLC-ESI-MS |

| Dopamine | Reward, motivation, motor control | Subtle concentration variations observed [14] | UPLC-ESI-MS |

| Norepinephrine | Arousal, alertness, stress | Subtle concentration variations observed [14] | UPLC-ESI-MS |

| Serotonin | Mood, appetite, sleep | Subtle concentration variations observed [14] | UPLC-ESI-MS |

| Acetylcholine | Learning, memory, attention | Measured via its precursor, Choline [14] | UPLC-ESI-MS |

Table 2: Comparison of ntPET Methodologies for Estimating Neurotransmitter Kinetics

| Feature | ART (Arteral) Method | REF (Reference) Method | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tracer Input Function (TIF) | Measured from arterial blood samples [19] | Derived from a reference brain region [19] | |

| Invasiveness | High (requires arterial cannulation) [19] | Low (non-invasive) [19] | |

| Cost & Complexity | High (burdensome sample processing) [19] | Low (simplified protocol) [19] | |

| Key Assumption | Plasma radioactivity accurately reflects tracer input | Reference region has negligible receptor density [19] | |

| Robustness to Metabolites | Deteriorates with uncorrected radiometabolites [19] | Not applicable | N/A |

| Robustness to Reference Region Binding | Not applicable | Performance preserved even with 40% receptor density in reference region [19] | N/A |

| Temporal Precision | Better than 3 minutes for early NT peaks [19] | Better than 3 minutes for early NT peaks [19] |

Visualization of Workflows and Signaling

The following diagrams, generated with Graphviz DOT language, illustrate the core experimental and conceptual frameworks.

Microdialysis Workflow

ntPET Kinetic Modeling

Network Pharmacology Paradigm

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Systems Pharmacology and Target Site Measurement

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Example Sources / Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Microdialysis Probes & Guides | Semi-chronic implantation for repeated sampling in awake, behaving subjects [14]. | Custom or commercial systems (e.g., CMA Microdialysis) |

| UPLC-ESI-MS System | High-sensitivity quantification of a broad spectrum of neurotransmitters from small sample volumes [14]. | Waters, Agilent, Sciex |

| Radio-labeled PET Tracers | Molecules that bind to specific neuroreceptors, enabling quantification of receptor availability and NT release via displacement [19]. | Cyclotron-produced isotopes (e.g., 11C, 18F) |

| Drug-Target Databases | Provide curated information on known and predicted interactions between drugs and their protein targets [20]. | DrugBank, ChEMBL, SwissTargetPrediction |

| Protein-Protein Interaction Databases | Supply high-confidence data on physical and functional interactions between proteins for network construction [20]. | STRING, BioGRID, IntAct |

| Pathway Analysis Tools | Identify biological pathways overrepresented in a set of genes or proteins derived from network analysis [20]. | KEGG, Reactome, DAVID, g:Profiler |

| Network Visualization Software | Enable the construction, visualization, and topological analysis of complex drug-target-disease networks [20]. | Cytoscape, Gephi, NetworkX |

| Sofosbuvir D6 | Sofosbuvir D6, MF:C22H29FN3O9P, MW:535.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Pasireotide L-aspartate salt | Pasireotide (L-Aspartate Salt) | Pasireotide (L-aspartate salt) is a multireceptor-targeted somatostatin analog for endocrine and oncology research. This product is for research use only (RUO). |

Executing Microdialysis Studies: From Probe Implantation to Advanced Analytics

Microdialysis is an in vivo sampling technique that enables the monitoring of neurotransmitters and other molecules in the interstitial fluid of tissues, particularly the brain [12]. This method is based on the implantation of a probe containing a semi-permeable membrane into the region of interest. The probe is perfused with a solution that closely mimics the ionic composition of the extracellular fluid, allowing substances to diffuse across the membrane based on concentration gradients [13]. The design of the microdialysis probe—encompassing its membrane material, molecular weight cut-off (MWCO), and physical configuration—is paramount to the success of an experiment. These factors collectively determine the efficiency of analyte recovery, the spatial resolution of the sampling, and the degree of tissue response, all of which are critical for generating reliable and interpretable neurochemical data [21] [11].

This application note provides a structured overview of the key considerations for probe design and selection, framed within the context of measuring neurotransmitters in awake, freely moving animals. It is intended to serve as a practical guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals engaged in in vivo research.

Membrane Types and Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO)

The dialysis membrane is the core component of a microdialysis probe, and its characteristics directly govern which molecules are sampled.

Membrane Materials

Membranes are typically fabricated from regenerated cellulose or synthetic polymers, each with distinct properties [22].

- Regenerated Cellulose: These membranes are highly hydrophilic and exhibit low protein adsorption. However, their surface hydroxyl groups can activate the complement system, leading to reduced hemocompatibility [22].

- Synthetic Polymers: This category includes materials such as polysulfone, polyethersulfone, and polyacrylonitrile. Synthetic membranes are characterized by their asymmetric structure, which features a thin inner selective layer and a supportive outer layer. They offer superior biocompatibility, reduced activation of blood components, and greater flexibility in tuning pore sizes and surface characteristics [22].

Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO)

The MWCO is a critical parameter that defines the size-exclusion properties of the membrane. It is most often defined as the lowest molecular weight of a standard globular solute for which the membrane retains greater than 90% of the solute [23] [24]. It is crucial to understand that MWCO is a nominal rating and not an absolute barrier; diffusion of molecules near the specified MWCO will be slower compared to significantly smaller molecules [23].

The following table summarizes the retention characteristics of membranes with different MWCO ratings, demonstrating how retention increases with solute molecular mass.

Table 1: Molecular Weight Cut-Off (MWCO) and Analyte Retention Profiles for Dialysis Membranes

| Nominal MWCO | Analyte Retention Characteristics |

|---|---|

| 2 kDa | Retains >90% of molecules ~2,000 Da and larger; significantly slower dialysis rates for small ions due to thicker membrane and smaller pores [23]. |

| 3.5 kDa | Retains ~90% of a ~3,500 Da globular protein; allows efficient passage of small molecules like salts [23]. |

| 7 kDa | Retains >90% of a ~7,000 Da peptide; suitable for sampling small neurotransmitters while retaining some neuropeptides [23]. |

| 10 kDa | Retains proteins with a molecular mass ≥10,000 Da; a common choice for sampling classic neurotransmitters (e.g., glutamate, GABA, monoamines) [23]. |

| 20 kDa | Retains the majority of large proteins; enables sampling of a broader range of neuropeptides and larger molecules [23]. |

For neurochemical studies, probes with MWCO values ranging from 20,000 to 60,000 Da are commonly employed [21]. This range is optimal for sampling small-molecular-weight neurotransmitters such as monoamines and amino acids while effectively excluding larger macromolecules like proteins. This yields a protein-free sample that typically requires no further cleanup before analysis [13]. When the target analytes are larger, such as neuropeptides, a membrane with a higher MWCO (e.g., 100 kDa) may be necessary, though recovery for these molecules often remains low (below 5%) due to their size [11].

Probe Configurations

The physical design of the microdialysis probe must be matched to the target tissue and the experimental goals. The most common configurations are detailed below.

Table 2: Common Microdialysis Probe Configurations and Their Applications

| Probe Configuration | Physical Description | Typical Applications | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Concentric Cannula | Stainless steel shaft with a short dialysis membrane (1-4 mm) at the tip [21]. | Neuroscience research in specific brain regions of rodents [21]. | Offers high spatial resolution. Outer diameter typically 200-500 μm for rat brain studies [21]. |

| Linear (Side-by-Side) | A dialysis membrane (4-10 mm) bridging two pieces of flexible tubing [21]. | Sampling soft, homogeneous tissues like liver, muscle, heart, and skin [21]. | Larger surface area for sampling; less spatial precision than concentric design [21]. |

| Flexible | Similar to concentric design but uses flexible tubing to minimize vessel damage [21]. | Intravascular sampling from blood vessels [21]. | Can bend with animal movement; analyte recoveries are generally higher from blood [21]. |

| Shunt | Designed to sample from flowing fluids in vivo or in vitro [21]. | Sampling bile in awake animals or desalting protein samples [21]. | Allows continuous sampling from ductal systems. |

Experimental Protocol: Simultaneous Measurement of Neurotransmitters and Neuronal Activity

This protocol details a procedure for integrating microdialysis with local field potential (LFP) recordings to study the effects of amyloid-beta oligomers (Aβo) on hippocampal glutamate and GABA levels and neuronal hyperactivity in rats [25] [26].

Materials and Reagents

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Microdialysis and Neurotransmitter Analysis

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Amyloid-beta (1-42) | Preparation of amyloid-beta oligomers (Aβo) to model Alzheimer's disease pathology [25]. | Reconstituted according to established protocols to form soluble oligomers [25]. |

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | Perfusion solution for the microdialysis probe [6]. | Ionic composition similar to extracellular fluid (e.g., 147 mM Na+, 4 mM K+, 2.3 mM Ca2+, 155.6 mM Cl-) [6]. |

| Microdialysis Probe | In vivo sampling device [21]. | Concentric design with a MWCO of 50,000 Da, suitable for sampling glutamate and GABA [6]. |

| LFP Electrode | Recording neuronal activity [25]. | Custom-assembled electrode coupled to the microdialysis cannula [25]. |

| HPLC System with Detector | Quantitative analysis of neurotransmitters in dialysate [6]. | High-performance liquid chromatography with electrochemical detection (HPLC-ECD) [6]. |

| Mass Spectrometry | Highly sensitive and selective analysis of neurotransmitters [11]. | Used as an alternative or complementary method to HPLC for glutamate and GABA quantification [25]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

- Probe and Electrode Assembly: Assemble a custom complex that integrates a microdialysis cannula with an LFP recording electrode. Ensure the dialysis membrane at the tip and the electrode contacts are properly aligned [25].

- Surgical Implantation: Anesthetize the rat and secure it in a stereotaxic apparatus. Implant the assembly complex into the target hippocampal region using stereotaxic coordinates. Fix the assembly firmly to the skull using dental cement [25] [6].

- Post-operative Recovery: House the animal individually and allow it to recover for 2-3 days after surgery before commencing experiments [6].

- Simultaneous LFP Recording and Microdialysis:

- Connect the implanted probe to a microsyringe pump and perfuse with aCSF at a flow rate of 2.0 μL/min [6].

- Connect the LFP electrode to the recording system.

- Place the rat in a testing cage where it can move freely.

- Collect dialysate samples automatically at set intervals (e.g., every 25 minutes) and inject them directly into the HPLC system [6].

- Record LFP signals continuously throughout the session.

- Baseline and Intervention:

- Collect at least four dialysate samples to establish stable baseline levels of neurotransmitters and LFP activity.

- Administer the intervention (e.g., intracerebral injection of Aβo or systemic drug administration) [25] [6].

- Continue collecting dialysate samples and LFP data for the desired post-intervention period.

- Sample Analysis: Analyze the dialysate samples using HPLC-ECD or LC-MS/MS to quantify concentrations of glutamate, GABA, and other neurotransmitters of interest [25] [6].

- Histological Verification: Upon experiment completion, perfuse the brain with a dye or fixative, remove the brain, and verify the probe and electrode placement histologically [6].

The workflow for this integrated protocol is as follows:

Critical Factors Influencing Probe Performance

Recovery and Flow Rate

Recovery refers to the efficiency with which an analyte is collected from the extracellular fluid into the dialysate. It is a central concept in microdialysis quantification [12].

- Relative Recovery: The concentration of the analyte in the dialysate divided by its concentration in the external medium. It is inversely related to flow rate [12] [11].

- Absolute Recovery: The total mass of an analyte collected per unit of time. It is directly related to flow rate [11].

For high relative recovery of neurotransmitters, lower flow rates (e.g., 0.1 - 1.0 μL/min) are recommended as they allow more time for analyte equilibration across the membrane [11]. However, this results in lower sample volumes, which can challenge analytical detection. A balance must be struck based on the sensitivity of the analytical method.

Tissue Considerations and Limitations

Probe implantation inevitably causes tissue trauma, including inflammation, hemorrhage, and gliosis (the development of a fibrin-like polymer around the probe) [21]. This glial scar can act as a physical barrier, increasing the diffusional distance and adversely affecting recovery over time [21] [11]. To mitigate this:

- Allow a recovery period of ~24 hours after probe implantation before starting experiments to stabilize the initial tissue response [21].

- Consider using smaller, miniaturized probes to reduce tissue damage and improve spatial resolution [11].

- The use of retrodialysis with anti-inflammatory agents (e.g., dexamethasone) has been shown to reduce glial scarring [11].

The careful selection and design of a microdialysis probe are foundational to successful in vivo neurochemical monitoring. The choice of membrane material and its MWCO determines the selectivity of sampling, while the probe configuration must be suited to the anatomical site. Furthermore, critical operational parameters like flow rate directly impact analyte recovery and temporal resolution. By understanding and optimizing these factors—as outlined in this application note—researchers can robustly apply microdialysis to investigate the dynamic changes in neurotransmitters that underlie behavior, disease states, and drug effects.

Surgical Implantation and Guide Cannula Placement in Rodent Brain Regions

This application note provides a detailed protocol for the surgical implantation of guide cannulas into specific brain regions of rodents, a foundational technique for in vivo research methodologies such as microdialysis. Microdialysis is a critical in vivo sampling technique that allows for the measurement of neurotransmitters, metabolites, and drugs in the extracellular fluid of discrete brain regions of awake, freely-moving animals [17]. The successful implementation of this procedure enables researchers to investigate the neurochemical correlates of behavior and the pharmacodynamic profiles of drugs for disorders such as addiction, Parkinson's disease, and depression [17]. This guide details the materials, surgical steps, and post-operative care required for reproducible and minimally invasive cannula implantation.

Experimental Protocols

Pre-Surgical Preparation

- Animals: Adult rodents (mice or rats) are housed under standard conditions with ad libitum access to food and water.

- Anesthesia: Prepare an anesthetic mixture. For mice, one effective protocol uses a mixture of medetomidine hydrochloride (0.3 mg/kg), butorphanol tartrate (5.0 mg/kg), and midazolam (4.0 mg/kg) administered via intraperitoneal (i.p.) injection [27]. Ensure the depth of anesthesia is sufficient by checking for the absence of pedal and corneal reflexes.

- Stereotaxic Instrument Setup: Secure the anesthetized animal in the stereotaxic frame using ear bars and a bite bar. Maintain body temperature using a heated pad. Apply ophthalmic ointment to prevent corneal drying. Shave the scalp and disinfect the surgical site with alternating scrubs of iodine and ethanol [28].

Surgical Implantation Procedure

- Incision and Skull Exposure: Make a midline incision of the scalp (~1.5-2 cm) and retract the skin and underlying fascia to clearly expose the skull [28].

- Skull Preparation and Landmark Identification: Gently scrape the skull surface with a scalpel blade to create an uneven surface, which improves the adhesion of the subsequent dental cement [28]. Identify the cranial landmarks, bregma and lambda, and ensure the skull is level by confirming the dorsoventral (DV) coordinate at both points is equal.

- Stabilizing Screw Placement: Drill two small holes into the skull, away from the cannula implantation site, using an 18-gauge needle or a surgical drill. Anchor miniature steel screws into these holes; they will provide structural support for the dental cement head-cap [27] [28].

- Cannula Targeting and Implantation:

- Calculate the target coordinates for your brain region of interest relative to bregma. For example, for targeting the BNST in mice, coordinates may be: Anteroposterior (AP): +1.6 mm, Mediolateral (ML): -0.5 mm, Dorsoventral (DV): -4.1 mm from the dura [27].

- Raise the guide cannula and drill a burr hole at the calculated AP and ML coordinates.

- Lower the guide cannula slowly to the target DV coordinate. For bilateral injections where cannulas may interfere, they can be implanted at a 60° angle to the vertical axis [27].

- Securing the Cannula: Prepare dental acrylic cement (e.g., GC Unifast II). Mix the powder and liquid to a viscous consistency and apply it around the base of the guide cannula and the stabilizing screws, forming a stable head-cap [27]. Ensure the cement does not obstruct the cannula lumen.

- Wound Closure and Recovery: After the cement has fully hardened, carefully retract the stereotaxic arm. Insert a dummy cannula into the guide cannula to prevent occlusion [27]. Suture the skin around the head-cap if necessary. Administer a reversal agent for the anesthesia (e.g., atipamezole for medetomidine) if applicable, and place the animal in a warmed recovery cage until it is fully ambulatory. Post-operative analgesia (e.g., Meloxicam) should be provided [28].

Post-Operative Care and Drug Infusion

- Handling: Handle guide cannula-implanted mice daily for several days prior to behavioral testing to acclimatize them to the infusion procedure [27].

- Topical Analgesia: To manage post-surgical pain, a local anesthetic cream like EMLA (containing lidocaine and prilocaine) can be applied to the surgical site twice daily until behavioral experiments begin [27].

- Microinfusion Protocol:

- Connect the treatment (internal) cannula to a length of tubing pre-filled with your drug solution or artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF). The cannula is then connected to a microsyringe (e.g., 5-µL Hamilton syringe) mounted on an infusion pump.

- Gently remove the dummy cannula and insert the treatment cannula, which extends 1-2 mm beyond the guide cannula tip.

- Infuse the solution at a slow, controlled rate (e.g., 0.1 µL over 1 minute) [27].

- After the infusion is complete, leave the cannula in place for an additional period (e.g., at least 5 minutes) to allow for diffusion and prevent backflow along the injection track [27].

- Remove the treatment cannula, replace the dummy cannula, and return the animal to its home cage. Behavioral testing can typically begin after a set pre-treatment interval (e.g., 30 minutes).

Key Data and Specifications

Table 1: Exemplary Stereotaxic Coordinates for Guide Cannula Implantation in the Mouse BNST

| Hemisphere | Approach Angle | Anteroposterior (AP) | Mediolateral (ML) | Dorsoventral (DV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Right | Anterior (60°) | +1.6 mm from bregma | -0.5 mm from bregma | -4.1 mm from dura | [27] |

| Left | Posterior (60°) | -3.05 mm from bregma | -0.5 mm from bregma | -4.4 mm from dura | [27] |

Table 2: Anesthesia and Infusion Parameters

| Parameter | Specification | Protocol Reference |

|---|---|---|

| Anesthetic Cocktail | Medetomidine (0.3 mg/kg); Butorphanol (5.0 mg/kg); Midazolam (4.0 mg/kg) | [27] |

| Infusion Volume | 0.1 - 0.125 µL | [27] |

| Infusion Rate | 0.1 µL/min | [27] |

| Post-Infusion Dwell Time | ≥ 5 minutes | [27] |

Workflow and Signaling Visualizations

Surgical Workflow

Diagram Title: Guide Cannula Implantation Workflow

Microdialysis Principle

Diagram Title: Microdialysis Sampling Principle

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

| Item Name & Specification | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| Guide Cannula (e.g., AG-8; 8 mm length, o.d. = 0.5 mm) | Permanent guide surgically implanted to target brain region, allows repeated insertion of injection probe [27]. |

| Dummy Cannula (e.g., AD-8) | Occludes the guide cannula between infusions to prevent contamination and patency loss [27]. |

| Artificial Cerebrospinal Fluid (aCSF) | Physiological buffer used to dissolve drugs/compounds for infusion and as a vehicle control [27]. |

| Dental Acrylic Cement (e.g., GC Unifast II) | Forms a stable, hardened head-cap to secure the guide cannula and screws to the skull [27]. |

| Microsyringe (e.g., 5-µL Hamilton syringe) | Precision syringe used with an infusion pump to deliver nanoliter-to-microliter volumes of solution at a constant rate [27]. |

| Stereotaxic Frame | Apparatus to rigidly hold the animal's head and allow precise 3D navigation for cannula placement based on a brain atlas [27] [28]. |

| Hck-IN-1 | Hck-IN-1, CAS:1473404-51-1, MF:C16H11ClN6O3S, MW:402.81 |

| TMV-IN-10 | 2-Pyridin-3-yl-5-(3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl)-1,3,4-oxadiazole |

Accurate measurement of neurotransmitter dynamics in the living brain is fundamental to neuroscience research and neuropharmacology. Cerebral microdialysis stands as a versatile in vivo sampling technique that enables the continuous collection of unbound analytes from the extracellular fluid of specific brain regions in awake, freely-moving animals [11] [17]. The core principle of microdialysis involves implanting a probe with a semipermeable membrane into the tissue, perfusing it with a physiological solution, and collecting the dialysate for analysis [9]. However, a complete equilibrium is never achieved due to constant perfusate flow, meaning the analyte concentration in the dialysate is lower than the true extracellular concentration [9]. Consequently, determining a calibration factor, or recovery, is critical for quantifying true extracellular levels [9]. This Application Note details three established calibration methods—No-Net-Flux, Retrodialysis, and Low-Flow-Rate—providing structured protocols and recommendations to ensure robust and reliable data in neurotransmitter research.

Principles of Microdialysis Calibration

Calibration in microdialysis is essential because the concentration of an analyte measured in the dialysate (Cout) is only a fraction of its actual concentration in the extracellular fluid (CECF). The recovery is defined as the ratio Cout/CECF [9]. The selection of an appropriate calibration method depends on the experimental design, the nature of the analyte (endogenous or exogenous), and whether steady-state conditions can be achieved or are required [29] [9]. The three techniques covered herein are based on distinct principles, summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Key Microdialysis Calibration Methods

| Method | Principle | Best For | Key Advantage | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No-Net-Flux [9] [30] | Perfusing multiple known analyte concentrations; CECF and recovery are determined from the x-intercept and slope of the (Cout-Cin) vs. Cin plot. | Endogenous compounds (e.g., neurotransmitters) at steady state. | Provides a direct, model-free measure of CECF at steady state. | Requires steady state; time-consuming as multiple concentrations are perfused. |

| Retrodialysis [9] [30] [31] | Using the analyte itself or a similar calibrator; recovery = (Cin - Cout) / Cin. Assumes diffusion is equal in both directions. | Exogenous compounds (e.g., drugs); allows for real-time calibration. | Enables continuous monitoring of recovery during the experiment. | Not suitable for most endogenous compounds; requires a validated calibrator. |

| Low-Flow-Rate [9] | Perfusing with blank solution at varying low flow rates; recovery increases as flow rate decreases. CECF is estimated by extrapolating to zero flow. | Applications where tissue concentration is stable over a long period. | Conceptually simple. | Long calibration times to collect sufficient sample volume at low flows. |

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for selecting the most appropriate calibration method based on key experimental parameters.

No-Net-Flux Method

Principle and Workflow

The No-Net-Flux (ZNF) method is a steady-state technique used primarily for quantifying basal levels of endogenous neurotransmitters [9] [30]. The probe is perfused with at least four different concentrations of the analyte of interest (Cin), including zero, and the resulting dialysate concentration (Cout) is measured for each. The difference (Cout - Cin) is plotted against Cin. The x-intercept of the resulting regression line represents the point of no-net-flux, which is the true CECF. The slope of the line corresponds to the relative recovery [9] [30].

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Application: Determining basal extracellular concentration of a neurotransmitter (e.g., Dopamine, Glutamate).

Pre-experimental Considerations:

- Animal Model: Typically performed in rodents (rats or mice). The animal should be awake and freely moving in a cage system designed for microdialysis.

- Probe Implantation: A microdialysis guide cannula is surgically implanted into the brain region of interest (e.g., striatum, prefrontal cortex) under anesthesia. Animals are allowed to recover for 24-48 hours before the experiment to minimize acute tissue damage effects [11].

- Analytical Setup: Ensure the analytical method (e.g., HPLC-ECD, LC-MS/MS) is optimized for the target analyte with established sensitivity and linearity in the expected concentration range [11] [32].

Procedure:

- Prepare Perfusate Solutions: Prepare artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF) containing the analyte (e.g., dopamine) at several known concentrations (e.g., 0 nM, 5 nM, 10 nM, 20 nM). The concentrations should bracket the expected CECF.

- Insert Probe and Establish Basal Flow: Insert the microdialysis probe through the guide cannula and begin perfusing with blank aCSF at a constant flow rate (typically 1.0-2.0 μL/min) using a high-precision syringe pump.

- Equilibration Period: Allow the system to equilibrate for 1-2 hours after probe insertion to establish a stable baseline.

- Sample Collection for ZNF:

- Perfuse the first concentration of analyte (Cin1) for a sufficient period to reach steady state (typically 30-45 minutes).

- Collect 2-3 consecutive dialysate samples under steady-state conditions. The sample volume is determined by the flow rate and collection interval (e.g., 20 μL at 1 μL/min over 20 minutes).

- Immediately analyze each sample or store at -80°C to prevent degradation.

- Repeat steps 4a-4c for each of the remaining perfusate concentrations (Cin2, Cin3, Cin4). The order of concentrations should be randomized to minimize time-dependent effects.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the mean Cout for each perfused concentration Cin.

- For each concentration, calculate the net flux: (Cout - Cin).

- Plot net flux (Y-axis) against Cin (X-axis) and perform linear regression.

- The X-intercept (where Y=0) is the estimated CECF.

- The slope of the regression line is the relative recovery.

Retrodialysis Method

Principle and Workflow

Retrodialysis (or reverse dialysis) is a powerful method for calibrating the delivery and sampling of exogenous compounds, such as drugs [30] [31]. It operates on the principle that the diffusion of a molecule across the semipermeable membrane is equal in both directions. The probe is perfused with a known concentration of the drug (or a structurally similar calibrator), and the disappearance of the drug from the perfusate is measured. The recovery is calculated as (Cin - Cout) / Cin [9]. This recovery factor is then used to calculate CECF from Cout during subsequent drug sampling experiments.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Application: Determining the recovery of an exogenous drug (e.g., Zidovudine, Selinexor) for subsequent pharmacokinetic studies.

Pre-experimental Considerations:

- Calibrator Selection: For "Retrodialysis by Drug," the drug itself is used. For "Retrodialysis by Calibrator," a compound with very similar physicochemical properties (e.g., size, lipophilicity, diffusion coefficient) must be selected and validated in vitro [30].

- Stability and Binding: Assess the drug's stability in the perfusate and its potential for non-specific binding to the tubing and probe components. For hydrophobic drugs, adding agents like bovine serum albumin (BSA) or DMSO to the perfusate may be necessary to minimize binding and improve recovery [29].

Procedure:

- In Vitro Validation (Recommended): Before the in vivo experiment, validate the recovery and calibrator similarity in a beaker containing stirred aCSF (with or without BSA) at 37°C [29]. This confirms the probe's functionality and the calibrator's suitability.

- In Vivo Calibration:

- Prepare the perfusate solution containing a known concentration of the drug or calibrator (Cin).

- Implant the probe and begin perfusion with blank aCSF as in the ZNF protocol. After equilibration, switch the perfusion line to the drug-containing solution.

- Allow the system to equilibrate (e.g., 60 minutes) for the loss of drug to stabilize.

- Collect multiple consecutive dialysate samples (e.g., 3 samples over 60-90 minutes).

- Measure the concentration of the drug/calibrator in the collected dialysate (Cout).

- Switching to Sampling Mode: To begin the actual experiment, switch the perfusate back to blank aCSF. After a washout period, administer the drug systemically (e.g., intraperitoneally or intravenously) and collect dialysate samples to measure Cout of the drug over time.

- Data Analysis:

- Calculate the relative recovery (RR) from the retrodialysis phase: RR = (Cin - Cout) / Cin.

- For each sample collected during the systemic drug experiment, calculate the true extracellular concentration: CECF = Cout / RR.

Low-Flow-Rate Method

Principle and Workflow

The Low-Flow-Rate method leverages the inverse relationship between flow rate and relative recovery [9]. At very low flow rates, the dialysate has more time to equilibrate with the extracellular fluid, increasing recovery. By perfusing the probe with blank solution at several low flow rates and measuring Cout, one can extrapolate the data to a theoretical flow rate of zero, where Cout would equal CECF.

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Application: Estimating CECF when the tissue concentration is stable over an extended period.

Procedure:

- Probe Implantation and Equilibration: Implant the probe and perfuse with blank aCSF at a standard flow rate (e.g., 1.5 μL/min) for 1-2 hours to establish a baseline.

- Sample Collection at Multiple Flow Rates:

- Sequentially perfuse the probe with blank aCSF at a series of decreasing flow rates (e.g., 2.0, 1.0, 0.5, 0.2 μL/min).

- At each flow rate, allow sufficient time for the system to stabilize (this can take 60-90 minutes at the lowest rates).

- Collect multiple dialysate samples once Cout has stabilized at each flow rate.