Optimizing Cell Culture Conditions for Robust and Reproducible Drug Sensitivity Testing

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing cell culture conditions to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of drug sensitivity testing.

Optimizing Cell Culture Conditions for Robust and Reproducible Drug Sensitivity Testing

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing cell culture conditions to enhance the accuracy and reproducibility of drug sensitivity testing. It covers foundational principles of cell viability assays and the impact of culture conditions on drug response. The content explores advanced methodological approaches, including 3D culture models and high-throughput screening protocols. A significant focus is given to troubleshooting common experimental pitfalls and optimizing critical parameters like cell seeding density and media composition. Finally, the article examines validated drug response metrics and AI-driven approaches for data analysis, offering a holistic framework for improving preclinical drug screening outcomes.

Laying the Groundwork: Principles and Pitfalls in Cell-Based Drug Screening

The Critical Link Between Cell Culture Conditions and Drug Response Reproducibility

Welcome to the Cell Culture Troubleshooting Hub

This resource center is designed to help researchers identify and resolve common issues that compromise the reproducibility of drug sensitivity testing. The guides and FAQs below are framed within the broader thesis that meticulous optimization of cell culture conditions is not just a preliminary step, but a critical and continuous requirement for generating reliable, translatable data in drug development.

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Cell Culture Issues Affecting Drug Response

| Problem Phenomenon | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions & Preventive Measures |

|---|---|---|

| High inter-laboratory variability in GR50/IC50 | • Use of different cell viability assays (e.g., image-based count vs. ATP-based) [1]• Variation in cell culture medium composition and serum batches [2]• Differences in cell seeding density and passage number [1] | • Standardize viability assays across all experiments; validate surrogate assays against direct counts for each drug [1].• Use identical, high-quality medium and serum batches from the same supplier for a study series [2].• Optimize and document seeding density to ensure consistent proliferation rates without confluence at endpoint [1]. |

| Inconsistent dose-response curves & high replicate variance | • Evaporation from drug dilution and assay plates, leading to drug concentration spikes [2]• Inappropriate DMSO vehicle control concentration [2]• "Edge effects" from uneven incubator conditions [2] | • Use sealed plates (e.g., parafilm, PCR plate seals) for drug storage; avoid long-term storage of diluted drugs [2].• Use matched DMSO controls for each drug concentration instead of a single control [2].• Humidify incubators properly; use plate layouts that randomize or exclude edge wells [2]. |

| Poor cell growth or viability in control wells | • Microbial contamination (e.g., bacteria, fungi, mycoplasma) [3]• Toxic impurities in media or labware (e.g., endotoxins, detergents) [3] [4]• Incorrect incubation conditions (temperature, CO2, vibration) [4] | • Implement routine mycoplasma testing using PCR-based kits; practice strict aseptic technique [3].• Use qualified, cell culture-grade reagents and consumables; test new media batches [4].• Regularly calibrate incubators; ensure they are level and placed on stable, vibration-free surfaces [4]. |

| Altered cellular morphology or unexpected drug efficacy | • Genetic drift or cell line misidentification [3]• Changes in extracellular matrix (ECM) components in 3D cultures [5]• Drug-induced changes in cell size/metabolism, affecting ATP-based assays [1] | • Authenticate cell lines regularly (e.g., STR profiling); obtain cells from reputable cell banks [3].• Standardize and document the lot of ECM materials like Corning Matrigel matrix [5].• For drugs affecting metabolism, use direct cell counting methods instead of metabolic assays like CellTiter-Glo [1]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do we observe up to 200-fold differences in drug potency (GR50) when the same protocol is used by different labs? This extreme variability often stems from biological context-sensitive factors rather than just technical pipetting errors. A multi-center study found that the choice of cell viability assay is a major driver. For instance, ATP-based assays (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) and direct image-based cell counts can give vastly different results for drugs like Palbociclib because the drug alters cell size and ATP content, breaking the assumption that ATP is proportional to cell number [1]. Other factors include subtle differences in incubation conditions and the handling of drug stocks [1] [2].

Q2: How can evaporation affect my drug sensitivity results, and how do I prevent it? Evaporation from drug dilution plates or assay plates concentrated your drugs and culture medium, leading to falsely elevated potency estimates (lower IC50/GR50). One study showed that storing diluted drugs in 96-well plates at 4°C or -20°C for just 48 hours significantly altered cell viability readings due to evaporation [2]. Prevention: For drug storage, use sealed PCR plates with aluminum tape instead of standard culture microplates, as they are less prone to evaporation. For long-term assays, ensure incubators are properly humidified and consider using microplates specifically designed to minimize evaporation [2].

Q3: My cell lines are growing poorly, and drug responses are erratic. What are the first things I should check? Begin with these fundamental checks:

- Contamination: Rule out microbial contamination, especially mycoplasma, which can alter cell growth and metabolism without causing visible cloudiness [3].

- Culture Technique: Ensure consistent and gentle mixing of the cell inoculum to avoid foam and bubbles, which can hinder uniform attachment and growth [4].

- Culture Conditions: Verify that your incubator maintains a stable temperature, CO2 level, and humidity. Position cultures away from the door to minimize fluctuations from frequent opening [4].

- Reagents: Check the expiration dates of your media, serum, and supplements. Test a new batch of serum or media to rule out reagent-specific issues [4].

Q4: When testing patient-derived organoids (PDOs), how can I improve the consistency of IC50 calculations between different operators? Recent research highlights several key strategies:

- Calculation Method: For PDOs, IC50 values derived from GraphPad's Dose-response-Inhibition (DRI/logit) and LC-logit methods show minimal variation even when the number of drug concentrations is reduced [6].

- Alternative Metrics: Consider using the Area Under the dose-response Curve (AUC), which correlates strongly with IC50 and often demonstrates lower variance between technical replicates [6].

- Technical Consistency: Use opaque-bottom plates instead of transparent-bottom plates for luminescent viability assays, as they yield higher measurement precision [6].

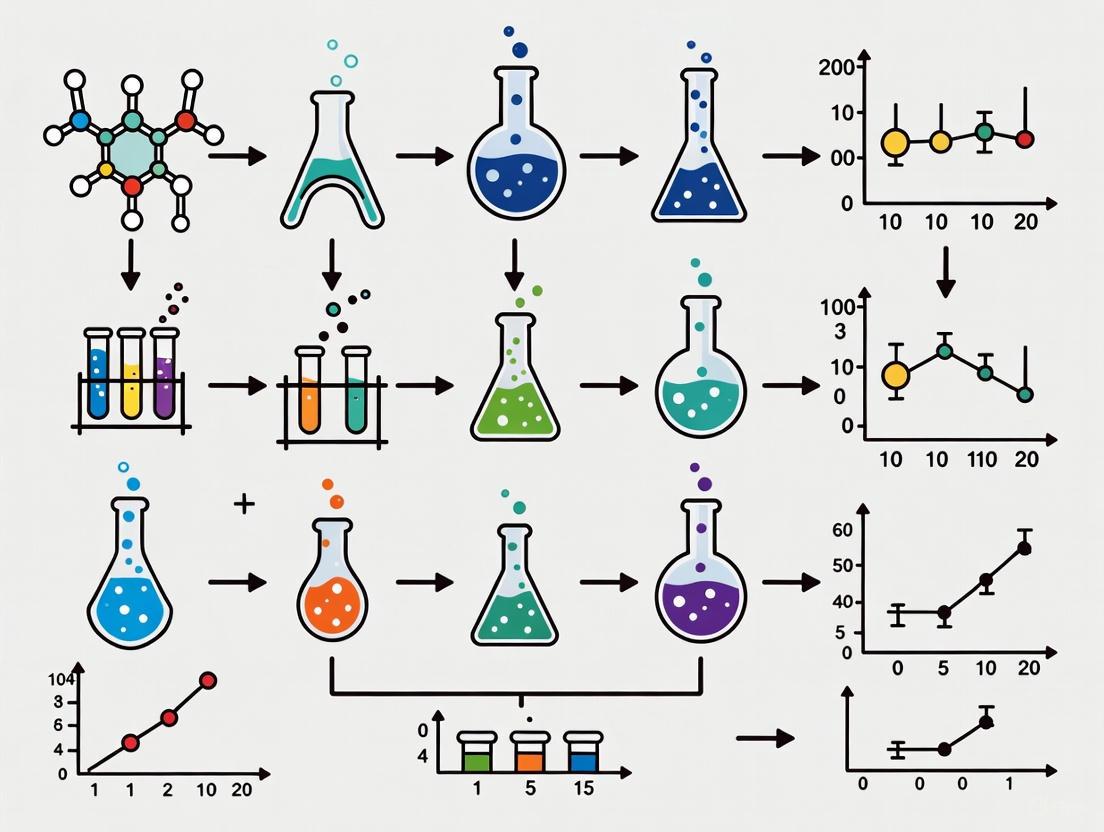

Experimental Protocol: Optimizing a Drug Sensitivity Assay

The following workflow, based on published reproducibility studies [2], provides a detailed methodology for optimizing a 2D cell-based drug sensitivity assay to minimize variability.

Step-by-Step Methodology:

- Define Baseline Protocol: Begin with standard, literature-based parameters. For example, plate cells at a common density (e.g., 1.0 × 10ⴠcells/well in a 96-well plate) in a serum-free medium to avoid serum-induced reduction of drug activity [2].

- Identify Confounders: Systematically test potential sources of error.

- Evaporation: Store diluted drugs in different plate types (e.g., standard culture microplates vs. sealed PCR plates) at 4°C and -20°C for 48-72 hours. Measure volume loss and test the effects on cell viability [2].

- DMSO Toxicity: Treat cells with a range of DMSO concentrations (e.g., 0.1% to 5%) for the assay duration. Cell viability decreases substantially with as little as 1% DMSO, necessitating matched vehicle controls [2].

- Edge Effects: Incolate a plate where all wells contain the same treatment (e.g., DMSO control). Measure the viability in all wells after incubation. Elevated readings in perimeter wells confirm an edge effect [2].

- Test & Optimize Parameters: Implement solutions based on your findings.

- Use sealed plates for drug storage and pre-warm media to reduce condensation-related issues.

- Include a DMSO vehicle control that matches the concentration present in each drug dose.

- Use plate layouts that exclude perimeter wells or fill them with PBS, randomizing the positions of treatments and controls.

- Establish Quality Control (QC) Metrics: Calculate metrics like the Z-factor to ensure your optimized assay is robust. A Z-factor > 0.5 indicates an excellent assay suitable for screening [2].

- Validate with Controls: Finally, run the fully optimized assay using a well-characterized cell line (e.g., MCF7) and a control drug (e.g., Bortezomib) to generate reference dose-response curves and potency values (IC50, GR50) [2].

Table 1: Impact of Assay Parameters on Cell Viability Measurements. Data synthesized from systematic investigations into replicability of drug screens [2].

| Parameter Tested | Condition 1 | Condition 2 | Effect on Cell Viability (IC50/AUC) | Key Finding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug Storage & Evaporation | 48h at 4°C in culture plate | 48h at -20°C in culture plate | Significant decrease in IC50 for both | Location (4°C vs. -20°C) had no effect, but evaporation occurred in both, concentrating the drug [2]. |

| Drug Storage & Evaporation | 72h in culture plate (Parafilm) | 72h in PCR plate (Aluminum tape) | N/A | Evaporation rate was significantly faster in standard culture microplates compared to sealed PCR plates [2]. |

| DMSO Vehicle Control | Single 1% DMSO control | Matched DMSO controls | Viability >100% at start of curve with single control | Using a single, high-concentration DMSO control for all doses led to artifactual dose-response curves [2]. |

| Viability Assay Method | Image-based cell count | ATP-based (CellTiter-Glo) | GRmax differed by 0.57 for Palbociclib | Discrepancy is drug-dependent; ATP assays are unreliable for drugs that alter cell size or metabolism [1]. |

| Plate Type for Luminescence | Transparent-bottom plate | Opaque-bottom plate | N/A | Opaque-bottom plates yielded higher precision in cell viability measurements for PDO-based assays [6]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Key Materials and Reagents for Reproducible Drug Sensitivity Assays.

| Item | Function & Importance in Drug Screens |

|---|---|

| Corning Matrigel Matrix | A basement membrane extract used for establishing 3D organoid and spheroid cultures. It provides a physiologically relevant microenvironment for studying tumor biology and drug response [5]. |

| Validated Cell Line Stock | Authenticated, low-passage cell stocks obtained from reputable banks (e.g., ECACC). Critical for preventing genetic drift and misidentification, which are major sources of irreproducible data [3]. |

| Characterized Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | A complex supplement providing growth factors and nutrients. Batch-to-batch variability can significantly alter cell growth and drug response; therefore, testing and using large, single batches for a study is essential [3] [2]. |

| DMSO (Cell Culture Grade) | A common solvent for water-insoluble drugs. Must be used at the lowest possible concentration (typically <0.5%) with matched vehicle controls for each dose to avoid solvent toxicity confounding results [2]. |

| Spheroid Microplates / ULA Plates | Microplates with ultra-low attachment (ULA) surfaces or specialized geometry to promote the formation and maintenance of 3D spheroids and organoids for more predictive screening models [5]. |

| Quality Control Assays (e.g., Mycoplasma Tests) | Routine use of PCR- or enzyme-based kits to detect microbial contamination, particularly mycoplasma, which can alter cell physiology and drug sensitivity without visible signs [3]. |

| Silibinin | Silibinin, CAS:1265089-69-7, MF:C25H22O10, MW:482.4 g/mol |

| DL-alpha-Tocopherol | Alpha-Tocopherol |

Core Principles and Mechanisms

What are the fundamental principles behind WST-1 and resazurin assays?

Both WST-1 and resazurin assays are colorimetric methods that measure cellular metabolic activity as a proxy for cell viability. Despite this common goal, they operate through distinct biochemical mechanisms.

WST-1 Assay Principle: The WST-1 assay utilizes a tetrazolium salt that is cleaved by mitochondrial dehydrogenases in metabolically active cells. This reaction requires an intermediate electron acceptor to shuttle electrons from the cellular metabolic pathways to the WST-1 molecule, resulting in the production of a water-soluble formazan dye. The amount of formazan produced is directly proportional to the number of viable cells and can be quantified by measuring absorbance at 440-450 nm using a microplate reader [7].

Resazurin Assay Principle: Also known as the Alamar Blue assay, the resazurin assay employs a cell-permeable blue dye that is reduced primarily by mitochondrial enzymes within viable cells. This reduction converts resazurin to resorufin, a highly fluorescent pink compound that is released back into the culture medium. The fluorescence intensity, measured with excitation at 530-570 nm and emission at 580-620 nm, provides a reliable estimate of viable cell numbers [8].

The diagram below illustrates the key differences in the biochemical pathways of these two assays:

Comparative Analysis of Cell Viability Assays

How do different cell viability assays compare in performance characteristics?

The selection of an appropriate cell viability assay depends on multiple factors including sensitivity, detection method, and experimental requirements. The table below provides a comprehensive comparison of key assay types:

| Assay Type | Detection Method | Sensitivity | Incubation Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WST-1 | Absorbance (440-450 nm) | Generally higher than MTT, MTS [7] | 0.5-4 hours [7] | Water-soluble product; no solubilization required; suitable for time-course studies [7] | May require intermediate electron acceptor; higher background than MTT [7] |

| Resazurin | Fluorescence (Ex/Em: ~535/590 nm) | More sensitive than tetrazolium assays [8] | 30 min-4 hours (cell type dependent) [8] | Non-toxic at low concentrations; wide dynamic range; suitable for time-lapse experiments [8] | Fluorescence interference possible; incubation time critical [8] |

| MTT | Absorbance (570 nm) | Lower than WST-1 [7] | 1-4 hours [9] | Simple; widely used; inexpensive [9] | Formazan insoluble (requires solubilization); toxic to cells [9] |

| MTS | Absorbance (490-500 nm) | Intermediate between MTT and WST-1 [7] | 1-4 hours [10] | Water-soluble product; no solubilization required [10] | Requires intermediate electron acceptor [10] |

| ATP Assay | Luminescence | Excellent sensitivity and broad linearity [10] | 10 minutes [10] | Fast; sensitive; less prone to artifacts [10] | Requires cell lysis; endpoint measurement only [10] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Why might my viability assay show inconsistent results between replicates?

Inconsistent results often stem from improper assay optimization or technical artifacts. The following table addresses common issues and their solutions:

| Problem | Potential Causes | Recommended Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| High background signal | Culture medium components interfering with detection; incorrect wavelength settings; contaminated reagents [7] [8] | Include proper blank controls (medium + reagent only); optimize excitation/emission wavelengths for your cell type [8]; use fresh, filtered reagents [11] |

| Poor linearity with cell concentration | Incorrect incubation time; over- or under-confluent cells; depleted resazurin in high-density wells [8] | Optimize incubation time for each cell line; ensure cells are in log phase growth; perform cell titration experiments [8] [11] |

| Unexpectedly high signal in treated groups | Chemical interference from test compounds (antioxidants, reducing agents) [7] [9] | Include compound-only controls (no cells); consider alternative detection methods (e.g., ATP assay) [9] |

| Low signal-to-noise ratio | Suboptimal cell density; incorrect assay parameters; low metabolic activity [8] | Determine optimal seeding density empirically; validate wavelength selection for your cell type [11]; ensure healthy cell cultures |

| Inconsistent reduction in spheroids | Limited dye penetration due to tight cell-cell interactions [12] | Disrupt tight junctions mechanically or chemically; consider alternative viability assays for 3D models [12] |

How can I optimize resazurin assay parameters for my specific cell type?

Optimizing resazurin assays requires systematic evaluation of key parameters. Recent research demonstrates that applying standardized operating procedures can achieve measurement uncertainty of less than 10% [11]. Follow this workflow for optimal results:

Implementation Notes:

- Wavelength Optimization: Test various excitation/emission combinations within the resazurin spectra (e.g., λEx: 530, 535, 540, 545 nm paired with λEm: 585, 590, 595 nm) and select the combination providing the highest fluorescence intensity with minimal background [11].

- Incubation Time Determination: Evaluate different incubation periods (1-6 hours) across a range of cell densities. Optimal time provides linear response (R² > 0.99) between fluorescence intensity and cell number [8] [11].

- Assay Limits Establishment: Calculate Limit of Blank (LoB), Limit of Detection (LoD), and Limit of Quantification (LoQ) to define the reliable working range of your assay [11].

Experimental Protocols for Drug Sensitivity Testing

What is a standardized protocol for conducting drug sensitivity testing using viability assays?

The following protocol provides a robust framework for drug sensitivity testing (DST) applicable to both single-agent and combination therapy screening [13].

Materials Required:

- Cell line of interest (e.g., HeLa cells for cervical cancer studies)

- 96-well flat-bottom tissue culture plates

- WST-1 or resazurin assay reagent

- Test compounds at appropriate concentrations

- Microplate reader capable of absorbance/fluorescence detection

- Cell culture incubator (37°C, 5% CO₂)

Procedure:

- Cell Seeding: Harvest exponentially growing cells and seed into 96-well plates at optimized density. For adherent cells, typical densities range from 3,000-10,000 cells/well depending on growth rate.

- Pre-incubation: Incubate plates for 24 hours under standard culture conditions to allow cell attachment and recovery.

- Drug Treatment:

- Prepare serial dilutions of test compounds in culture medium.

- For combination studies, use checkerboard designs to evaluate multiple concentration ratios.

- Include vehicle controls and blank wells (medium only).

- Treatment Incubation: Incubate plates for desired exposure period (typically 48-72 hours for cytotoxicity assessment).

- Viability Assessment:

- WST-1 Method: Add 10 μL WST-1 reagent per 100 μL culture medium. Incubate for 0.5-4 hours until color development is sufficient. Measure absorbance at 440-450 nm with reference wavelength >600 nm [7].

- Resazurin Method: Add resazurin working solution (final concentration 10-44 μM). Incubate for optimized duration (1-6 hours based on cell type). Measure fluorescence at optimal wavelengths (e.g., λEx 535 nm/λEm 590 nm) [11].

- Data Analysis: Calculate percentage viability relative to untreated controls. Generate dose-response curves and determine ICâ‚…â‚€ values using appropriate software (e.g., SynergyFinder for combination studies) [13].

Research Reagent Solutions

What essential materials are required for implementing these viability assays?

The table below outlines key reagents and their functions in cell viability assessment:

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| WST-1 Assay Reagent | Tetrazolium salt cleaved by mitochondrial dehydrogenases to soluble formazan [7] | Use at 10 μL per 100 μL medium; requires intermediate electron acceptor for some formulations [7] |

| Resazurin Sodium Salt | Cell-permeable blue dye reduced to fluorescent resorufin by metabolically active cells [8] | Prepare fresh working solution (e.g., 44 μM); protect from light; filter-sterilize [11] |

| 96-well Tissue Culture Plates | Platform for cell growth and treatment | Use flat-bottom plates for adherent cells; ensure uniform cell seeding |

| Intermediate Electron Acceptors | Facilitate electron transfer for WST-1 reduction (e.g., 1-methoxy PMS) [7] | May be toxic to cells at high concentrations; requires optimization [7] |

| Microplate Reader | Detection of absorbance/fluorescence signals | Ensure appropriate filters/wavelengths; validate instrument performance regularly |

| Cell Culture Medium | Supports cell growth during treatment | Phenol-red free medium may reduce background for absorbance assays [7] |

Frequently Asked Questions

Can these viability assays be used for 3D cell culture models?

The application of viability assays to 3D cultures requires careful consideration. While resazurin assays are widely used for 3D models, recent research indicates that compact spheroids with tight cell-cell interactions may hamper resazurin uptake and reduction, potentially leading to underestimated viability [12]. Disruption of tight junctions through trypsinization or EDTA treatment can restore accurate measurement correlation [12]. For complex 3D models, consider validating results with multiple assay types or using ATP-based assays which may provide more reliable quantification.

How can I distinguish between cytotoxic and cytostatic effects in my experiments?

Distinguishing between these mechanisms requires complementary approaches:

- Time-course Analysis: Monitor viability at multiple time points. Cytotoxic compounds show progressive cell death, while cytostatic agents typically maintain viability at initial levels without progression to death.

- Multiplexing Approaches: Combine viability assays with direct cytotoxicity markers (e.g., LDH release, dead-cell proteases) [10]. This allows simultaneous assessment of viable and dead cell populations.

- Morphological Assessment: Complement quantitative data with visual inspection of cellular morphology.

- Recovery Experiments: Wash out compounds after treatment and monitor whether cells resume proliferation, indicating cytostatic rather than cytotoxic effects.

What are the critical considerations for assay validation in drug sensitivity testing?

Robust validation of viability assays for drug screening should address:

- Linearity and Range: Establish the linear range of the assay for your specific cell line through cell titration experiments [11].

- Precision: Determine repeatability (intra-assay) and reproducibility (inter-assay) variability, aiming for less than 20% imprecision [8].

- Specificity: Verify that assay signals specifically reflect viable cell metabolism through appropriate controls.

- Limits of Detection and Quantification: Define the minimum number of detectable and quantifiable cells [11].

- Interference Testing: Evaluate potential interference from test compounds, especially in fluorescence-based assays [8].

Implementing these validation parameters will enhance the reliability of your drug sensitivity data and facilitate comparisons across studies and laboratories.

How Cellular Metabolism and Microenvironment Influence Drug Efficacy

FAQs: Core Concepts and Troubleshooting

FAQ 1: Why do cancer cells in traditional 2D culture often show different drug sensitivity compared to in vivo tumors?

The primary reason is that traditional 2D culture fails to replicate the complex three-dimensional architecture and cellular interactions of the tumor microenvironment (TME). In 2D cultures [14]:

- Cells adopt a flat, unnatural morphology and exhibit rapid, uncontrolled proliferation.

- They lack cell-cell and cell-matrix communication, which are critical for maintaining proper cell polarity, differentiation, and function.

- This leads to altered gene expression and metabolism patterns, which are key determinants of drug sensitivity.

Consequently, drug responses observed in 2D-cultured cancer cells may not accurately reflect the behavior of tumors in vivo, where the TME imposes intense metabolic stress through nutrient competition and lactate-driven acidification [15].

FAQ 2: What are the key metabolic interactions in the TME that can lead to drug resistance?

The TME is an ecosystem where different cell types compete for resources and engage in metabolic crosstalk, often creating an immunosuppressive milieu that promotes drug resistance. Key interactions include [16]:

- Nutrient Competition: Tumor cells and immune cells, particularly T cells, compete for essential nutrients like glucose and amino acids. Tumor cells often outcompete T cells, leading to T cell dysfunction and impaired anti-tumor immunity.

- Lactate-Driven Acidification: Tumor cells preferentially use glycolysis, producing large amounts of lactate. This creates an acidic TME that suppresses the function of cytotoxic T cells and can promote the polarization of tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) towards a pro-tumor, M2-like state.

- Metabolic Support: Cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) can undergo metabolic reprogramming to produce energy-rich metabolites (like lactate and ketones) that are then used as fuel by cancer cells, a phenomenon known as the "reverse Warburg effect."

FAQ 3: Our lab is transitioning to 3D models. What are the common challenges in maintaining physiological relevance in 3D cultures for drug testing?

Successfully leveraging 3D models requires careful attention to culture conditions. Common challenges and their solutions include [14]:

- Challenge: Reproducibility and standardization of 3D spheroid/organoid formation.

- Solution: Utilize scaffold-based methods with defined extracellular matrix (ECM) substitutes like Corning Matrigel and employ automated liquid handling systems to improve consistency.

- Challenge: Inadequate nutrient and oxygen diffusion to the core of 3D structures, leading to necrotic centers that do not reflect viable tumor regions.

- Solution: Optimize the size of spheroids and consider dynamic culture systems (like bioreactors) to improve perfusion.

- Challenge: Failure to recapitulate the native tumor's cellular heterogeneity and stromal components.

- Solution: Develop co-culture systems that incorporate patient-derived cancer cells with relevant stromal and immune cells to better mimic the interactive TME.

Technical Guides: Methodologies and Protocols

Protocol: Establishing a Patient-Derived Tumor Organoid (PDTO) Model for Drug Sensitivity Testing

Patient-derived tumor organoids (PDTOs) preserve the genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of the original tumor, making them a superior model for predictive drug testing [14].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Sample Processing: Obtain fresh tumor tissue from surgical resection or biopsy. Mechanically mince the tissue and digest it with a collagenase/hyaluronidase solution to create a single-cell suspension or small cell clusters [14].

- 3D Embedding: Mix the cell suspension with a basement membrane extract, such as Corning Matrigel, which provides a scaffold that mimics the native extracellular matrix. Plate the mixture as droplets in pre-warmed culture dishes.

- Culture Conditions: Overlay the solidified Matrigel droplets with a specialized, bespoke growth factor media tailored to the specific tumor type. This media typically contains factors like R-spondin 1, Noggin, and Wnt3a to support stem cell expansion and organoid growth.

- Passaging and Biobanking: Once organoids are established and reach a sufficient size (typically after 1-3 weeks), they can be enzymatically dissociated and re-embedded in Matrigel for expansion. Aliquots can be cryopreserved to create a biobank.

- Drug Sensitivity Testing (Pharmacotyping): Harvest and dissociate organoids into single cells or small fragments. Re-embed them in Matrigel in a 96-well plate. After 3-5 days, treat with a concentration gradient of the anti-tumor drugs of interest. Incubate for a predetermined period (e.g., 5-7 days).

- Viability Assessment: Measure cell viability using assays like CellTiter-Glo 3D, which quantifies ATP levels as a proxy for metabolically active cells. Calculate the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) for each drug.

Protocol: Analyzing Drug-Induced Metabolic Changes Using Constraint-Based Modeling

Genome-scale metabolic models (GEMs) can be used to infer changes in metabolic pathway activity from transcriptomic data following drug treatment, providing insight into mechanisms of drug synergy [17].

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Methodology:

- Cell Treatment and RNA Sequencing: Treat cancer cells (e.g., the gastric cancer line AGS) with individual kinase inhibitors (e.g., PI3Ki, MEKi) and their synergistic combinations. Include a DMSO vehicle control. Extract total RNA and perform RNA-sequencing.

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) for each treatment condition compared to control using a standard pipeline with tools like the DESeq2 package. Perform gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to understand broad functional changes.

- Metabolic Modeling with TIDE: Use the Tasks Inferred from Differential Expression (TIDE) algorithm. This constraint-based method maps the DEGs onto a genome-scale metabolic model (GEM) like Recon3D.

- TIDE evaluates the ability of the context-specific metabolic network to carry out defined metabolic tasks (e.g., "ornithine biosynthesis") based on the expression of associated genes.

- It calculates a score for each task, indicating whether its activity is increased, decreased, or unchanged upon drug treatment.

- Synergy Scoring: Introduce a metabolic synergy score that compares the pathway activity changes in the combination treatment to those observed in the individual drug treatments. This helps identify metabolic processes specifically and strongly altered by the drug synergy, such as downregulation of ornithine and polyamine biosynthesis in the case of PI3Ki–MEKi combination [17].

Data Presentation: Quantitative Comparisons

Table 1: Comparison of 2D vs. 3D Cell Culture Models for Drug Sensitivity Testing

| Parameter | 2D Culture | 3D Culture |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Morphology | Flat, stretched | In vivo-like, 3D structure [14] |

| Cell Proliferation | Rapid, contact-inhibited | Slower, more physiologically relevant [14] |

| Cell Function & Differentiation | Simplified, incomplete | Maintains polarity and normal differentiation [14] |

| Cell-Cell & Cell-Matrix Communication | Limited | Extensive, mimics in vivo interactions [14] |

| Gene Expression & Metabolism | Altered patterns | Closer to native tumor profiles [14] |

| Predictive Value for Drug Efficacy | Lower, often overestimates | Higher, better correlates with clinical response [14] |

| Suitability for High-Throughput Screening | High | Moderate (improving with new technologies) [14] |

Table 2: Metabolic Pathways in Key TME Cell Types and Potential Therapeutic Targets

| Cell Type | Key Metabolic Features | Associated Drug Targets & Experimental Reagents |

|---|---|---|

| Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) | M1-like: Glycolysis; M2-like: Oxidative Phosphorylation (OXPHOS), Fatty Acid Oxidation (FAO) [16] | CSF-1R inhibitors (e.g., Emactuzumab), Glutaminase (GLS) inhibitors, drugs targeting Fatty Acid Synthase (FASN) [16] |

| Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) | "Reverse Warburg": Glycolysis, lactate production; Autophagy; Glutamine metabolism [16] | Monocarboxylate Transporter inhibitors (MCTi), CB-839 (Telaglenastat - GLS inhibitor), Chloroquine (autophagy inhibitor) [16] |

| T Cells (TILs) | Effector T cells: Glycolysis, OXPHOS; Dysfunctional T cells: Mitochondrial defects, lipid accumulation [15] [16] | Immune checkpoint blockers (anti-PD-1, anti-CTLA-4), DRP-104 (a prodrug of the glutamine antagonist DON), L-arginine to enhance T cell function [16] |

| Tumor Endothelial Cells (TECs) | Glycolysis, Fatty Acid Oxidation [16] | PFKFB3 inhibitors, VEGF/VEGFR inhibitors (anti-angiogenics) [16] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Advanced TME and Metabolism Research

| Research Reagent / Solution | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Corning Matrigel Matrix | A basement membrane extract used as a scaffold for 3D cell culture, enabling the formation of organoids and spheroids by providing a physiologically relevant environment for cell growth and signaling [14] [5]. |

| Seahorse XF Analyzer Consumables | Cartridges and culture plates designed for real-time, live-cell analysis of metabolic function, specifically measuring glycolysis and mitochondrial respiration (OXPHOS) rates [14]. |

| CellTiter-Glo 3D Cell Viability Assay | A luminescent assay optimized for 3D models that measures ATP content, providing a reliable indicator of cell viability and compound cytotoxicity in complex microtissues [14]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Tools for precise genome editing (e.g., knockout of metabolic genes) in cell lines or patient-derived organoids to identify novel metabolic vulnerabilities and validate drug targets [5]. |

| Lactate Assay Kits | Colorimetric or fluorometric kits for quantifying lactate concentration in cell culture media, a key readout for glycolytic flux in cancer cells and the TME [16]. |

| Recombinant Human IL-15 | A cytokine used in co-culture experiments to augment T-cell proliferation and activation, thereby improving the efficacy of therapies like CDK4/6 inhibitors in an immunosuppressive TME [18]. |

| beta-Damascenone | beta-Damascenone, CAS:23726-93-4, MF:C13H18O, MW:190.28 g/mol |

| 2-Furancarboxylic acid | 2-Furoic Acid|Furan-2-carboxylic Acid Supplier |

Signaling Pathways and Metabolic Crosstalk

Metabolic Crosstalk in TME

Diagram illustrating the key metabolic interactions between cells in the Tumor Microenvironment (TME). Cancer cells outcompete T cells for nutrients, while both cancer cells and Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts (CAFs) secrete lactate, further suppressing immune function. Tumor-Associated Macrophages (TAMs) polarized to an M2-state contribute to an immunosuppressive milieu [15] [16].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common sources of variability in 2D drug sensitivity screens? The most common sources of variability are often related to cell culture conditions, drug storage and preparation, and assay protocol design. Specifically, evaporation of drug solutions, DMSO solvent cytotoxicity, and suboptimal cell seeding density can significantly impact the replicability and reproducibility of your results [2].

FAQ 2: How can I improve the consistency of my dose-response curves? To improve consistency, optimize and standardize your cell culture and assay protocols. This includes using matched DMSO controls for each drug concentration to correct for solvent cytotoxicity, ensuring proper sealing of plates to prevent evaporation, and determining the optimal cell seeding density for your specific cell line to avoid overgrowth or poor signal dynamic range [2].

FAQ 3: Why do I get inconsistent IC50 values between replicate experiments? Inconsistent IC50 values can stem from suboptimal drug storage conditions or unaccounted-for edge effects in microplates. Storing diluted drugs for extended periods, even at -20°C, can lead to evaporation and drug concentration, altering the effective dose. Furthermore, an "edge effect"—where cells in perimeter wells show different viability—can introduce bias if not controlled for by excluding these wells or using plate layouts that account for it [2].

FAQ 4: What drug response metrics are more robust for interlaboratory comparison? While IC50 and Emax are common, metrics for growth rate inhibition (GR) have been shown to produce more consistent interlaboratory results. These include GR50, GRmax, and GRAOC (Area Over the Curve), as they account for differences in cellular division rates better than conventional metrics [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: High Background or Inconsistent Signal in Viability Assays

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Evaporation from drug and assay plates, leading to increased concentration of compounds and DMSO, which can be cytotoxic [2].

- Solution: Seal plates properly during storage and incubation. For long-term storage of diluted drugs, use sealed PCR plates instead of culture microplates, and avoid storing diluted drugs for more than 48 hours [2].

- Cause: Incorrect DMSO concentration across wells, leading to variable solvent toxicity [2].

- Solution: Use a matched DMSO vehicle control for each drug concentration rather than a single control for the entire plate. This ensures the DMSO concentration is consistent in all comparative wells [2].

- Cause: Suboptimal cell seeding density. Too few cells yield a weak signal; too many cells can lead to over-confluency and nutrient depletion by the end of the assay [2].

- Solution: Perform a cell titration experiment to determine the optimal cell number that keeps cells in the exponential growth phase throughout the assay duration without overgrowth. For example, for MCF7 cells in a 96-well format, a density of 7.5 × 10³ cells/well may be optimal [2].

Issue 2: Poor Replicability Between Technical Replicates

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Edge effects in microplates, where cells in outer wells exhibit different growth and viability due to increased evaporation [2].

- Solution: Use only the inner 60 wells of a 96-well plate for critical assays. Fill the perimeter wells with sterile PBS or medium to create a humidified buffer zone [2].

- Cause: Instability of the drug compound in the chosen storage condition or medium [2].

- Solution: Prepare fresh drug dilutions for each experiment. If this is not feasible, validate the stability of your compounds under your specific storage conditions (e.g., -20°C in sealed PCR tubes) over the intended storage period [2].

- Cause: Inconsistent cell health or passage number.

- Solution: Use cells at a consistent, low passage number. Ensure cells are healthy and not contaminated. Use standardized culture conditions, including the same batch of growth medium and serum [19].

Issue 3: Lack of Reproducibility Between Different Analysts or Labs

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Cause: Use of different drug response metrics that are sensitive to cellular growth rates [2].

- Solution: Adopt more robust growth rate-based metrics (GR) like GR50 and GRAOC instead of, or in addition to, traditional IC50 and AUC metrics [2].

- Cause: Variation in core cell culture protocols, such as medium composition (e.g., serum-free vs. serum-containing), assay incubation time, or the method of resorufin detection (absorbance vs. fluorescence) [2].

- Solution: Fully optimize and document all experimental parameters. Once optimized, create a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) to be followed by all analysts. For example, using growth medium with 10% FBS and a defined resazurin incubation time can improve reproducibility [2].

The table below summarizes key experimental parameters and their impact on cell viability data, based on variance component analysis [2].

Table 1: Major Sources of Experimental Variability in Pharmacogenomic Screens

| Source of Variability | Impact on Data | Recommended Optimization Strategy |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceutical Drug & Cell Line | High impact on viability. Primary factors in variability [2]. | Use well-characterized cell lines and drugs. Validate each new model system. |

| Drug Storage (Evaporation) | Significant. Alters effective drug concentration, affecting IC50 and AUC [2]. | Store diluted drugs at -20°C in sealed PCR plates for ≤48 hours; avoid 4°C storage [2]. |

| DMSO Solvent Concentration | High cytotoxicity at ≥1% v/v. Causes dose-response curves to start >100% viability [2]. | Use matched DMSO vehicle controls for each drug dose [2]. |

| Cell Seeding Density | Medium. Affects dynamic range and can lead to overgrowth [2]. | Titrate cell number; e.g., use 7.5 x 10³ cells/well for MCF7 in 96-well format [2]. |

| Assay Incubation Time & Growth Medium | Lower impact, but can be cell line-specific [2]. | Standardize medium (e.g., with 10% FBS) and incubation time across experiments [2]. |

Experimental Protocols

This protocol provides a step-by-step guide to optimize a common cell viability assay to minimize variability.

1. Determine Optimal Cell Seeding Density:

- Seed cells in a 96-well plate at a range of densities (e.g., from 2.5 x 10³ to 2.0 x 10ⴠcells/well) in 100 µL of growth medium supplemented with 10% FBS. Avoid antibiotics to prevent unintended effects on cell viability.

- Incubate the plate for 24, 48, and 72 hours at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO₂ incubator.

- At each time point, add 10 µL of 10% (w/v) resazurin solution directly to the wells. Incubate for 2-4 hours.

- Measure fluorescence (Ex/Em ~560/590 nm) or absorbance (~570 nm and ~600 nm as a reference).

- Calculate the signal-to-background ratio. The optimal density is the one that provides a robust signal (e.g., >3-fold over background) while ensuring cells remain in the exponential growth phase throughout the entire assay duration.

2. Mitigating Evaporation and Edge Effects:

- Drug Preparation: Prepare drug working solutions fresh on the day of the experiment. If storage is necessary, aliquot and store at -20°C in a tightly sealed PCR plate for no more than 48 hours.

- Assay Plate Setup: When setting up the drug treatment assay, use only the inner 60 wells. Fill the perimeter wells with 100-200 µL of sterile PBS to create a humidified chamber, minimizing the "edge effect."

3. Controlling for DMSO Cytotoxicity:

- Prepare a master plate of drug dilutions in a way that the DMSO concentration is serially diluted alongside the drug.

- For each concentration of the drug tested, include a vehicle control well that contains the same concentration of DMSO but no drug. This "matched control" is used to calculate 100% viability for that specific DMSO concentration.

4. Data Acquisition and Analysis:

- After adding resazurin and incubating, measure the signal.

- For each drug concentration, calculate the percentage of cell viability relative to its matched DMSO vehicle control.

- Use nonlinear regression to fit the dose-response curve and calculate metrics like IC50, GR50, or AUC. The use of GR metrics is encouraged for screens where cell proliferation rates may vary [2].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Robust Drug Screens

| Item | Function | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Resazurin Sodium Salt | A cell-permeable, blue dye reduced to pink, fluorescent resorufin in viable cells. Used as a viability indicator [2] [19]. | Prepare a 10% (w/v) stock solution in PBS. It is light-sensitive; store aliquots in the dark. Incubation time (2-4 hours) must be optimized. |

| Matched DMSO Vehicle Controls | Control wells containing the exact concentration of DMSO used in the corresponding drug test well. Corrects for solvent-specific cytotoxicity [2]. | Critical for accurate baseline (100% viability) measurement. Eliminates artifacts of variable DMSO concentration. |

| Sealed PCR Plates | For the short-term storage of diluted drug solutions. Superior seal to prevent evaporation compared to standard culture microplates [2]. | Use for storing drug working solutions at -20°C for no more than 48 hours. |

| Cell Line-Specific Growth Medium | Provides nutrients and factors for cell growth. The composition (e.g., serum content) can affect drug activity and cell health [2]. | Standardize the medium recipe and serum batch across experiments. Note that serum-free medium may enhance cytotoxicity for some drugs like Bortezomib [2]. |

| L-Cysteine hydrochloride hydrate | L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate | High-purity L-Cysteine Hydrochloride Monohydrate for research. Used in food, feed, and plant studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

| Metoprolol | Metoprolol | High-purity Metoprolol, a selective β1-adrenergic receptor antagonist. For Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. |

Experimental Workflow and Variability Analysis

The following diagram illustrates the workflow for identifying and controlling major sources of variability in pharmacogenomic screens.

Workflow for Identifying Experimental Variability

The diagram below shows the relative impact of different factors on cell viability based on variance analysis.

Relative Impact of Variability Sources

The Global Challenge of Antibiotic Resistance and Its Implications for Sensitivity Testing

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the recognized standards for antibacterial susceptibility testing, and why are they critical for my research? The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) recognizes specific consensus standards to ensure the accuracy and reproducibility of susceptibility testing. The primary standard is the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) M100 document, "Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing," which is updated annually [20] [21]. These standards provide the official susceptibility test interpretive criteria (STIC), or "breakpoints," which are the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values used to categorize bacterial isolates as susceptible, intermediate, or resistant to an antibacterial agent [20]. Adhering to these recognized standards is mandatory for generating clinically relevant data, ensuring consistency across laboratories, and satisfying regulatory requirements for drug development [21].

Q2: What is the difference between high-throughput screening (HTS) and high-content screening (HCS) in drug sensitivity testing? While both are automated screening methods, they serve different purposes:

- High-Throughput Screening (HTS) is optimized for speed, testing thousands of compounds in parallel, typically using a single readout (e.g., cell viability via luminescence) [22] [23].

- High-Content Screening (HCS), also known as high-content analysis (HCA), is slightly slower but provides a deeper, multi-parameter analysis of cellular phenotypes. It uses automated microscopy and image analysis to simultaneously assess multiple parameters, such as cell morphology, protein localization, and organelle function, in response to treatment [22] [23]. This makes HCS invaluable for understanding the complex mechanisms of drug action and resistance beyond simple cell death.

Q3: What are the primary mechanisms by which bacteria become resistant to antibiotics? Bacteria evolve through several mechanisms to evade antibiotics [24]:

- Intrinsic Resistance: Natural evolution leads to structural or functional changes, such as the absence of a drug's target (e.g., bacteria without cell walls are resistant to penicillin) [24].

- Acquired Resistance: Bacteria can become resistant through new genetic mutations or by acquiring resistance genes from other bacteria via horizontal gene transfer. This occurs through:

- Transformation: Uptake of naked DNA from the environment.

- Transduction: Transfer of DNA via bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria).

- Conjugation: Direct cell-to-cell transfer of genetic material [24]. These mechanisms can lead to specific resistance strategies, including neutralizing the antibiotic, pumping it out of the cell (efflux), or modifying the antibiotic's target site [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Common Cell Culture Issues in Drug Sensitivity Assays

| Problem | Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High variability in IC50 values | Inconsistent culture conditions (pH, temperature), contamination, or low cell viability at seeding. | Standardize culture protocols; implement strict quality control for reagents; ensure >95% cell viability at the start of experiments [25]. |

| Unusual charge heterogeneity in recombinant protein products (e.g., mAbs) | Post-translational modifications (deamidation, oxidation) driven by suboptimal culture conditions like elevated pH or temperature [25]. | Systematically optimize culture parameters (pH, temperature, feed components) using Design of Experiments (DOE) or machine learning approaches [25]. |

| Failure to induce resistance in continuous culture models | Inconsistent or sub-inhibitory drug pressure, allowing unrestricted growth of non-resistant cells. | Use automated continuous-culture devices like a morbidostat, which dynamically adjusts drug concentration to maintain a constant selection pressure [26]. |

| Poor predictive value of ex vivo drug testing | Assays relying on a single metabolic readout (e.g., ATP-based viability) may miss complex phenotypes like therapy-induced senescence [23]. | Complement metabolic assays with high-content imaging to capture multi-parameter data, including morphology, apoptosis, and specific biomarker levels (e.g., c-Met) [27] [23]. |

Table 2: Interpreting Unexpected Results in Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

| Scenario | Investigation | Corrective Action |

|---|---|---|

| A known susceptible strain falls in the resistant category. | Check quality control (QC) ranges for the antibiotic and method. Verify that the latest CLSI M100 breakpoints are being used [21]. | Repeat the test with fresh QC strains. Confirm the drug concentration in the assay medium. Consult the current year's CLSI M100 standard for interpretive criteria [20] [21]. |

| No zone of inhibition is observed in disk diffusion. | Confirm the organism's identity and typical susceptibility profile. Check for contamination. Verify the drug is not expired. | Test for intrinsic resistance. Use an alternative, CLSI-recommended method (e.g., broth dilution) to determine the Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) [26]. |

| Discrepancy between genotypic and phenotypic resistance results. | The resistance gene may be present but not expressed, or resistance may be mediated by an unknown or novel mechanism [24]. | Use phenotypic results (MIC) to guide clinical interpretation. Further investigate with transcriptional analysis or enzymatic functional assays [28]. |

Key Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Broth Dilution for Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) Determination

The MIC is the lowest concentration of an antimicrobial agent that prevents visible growth of a microorganism [26].

Materials:

- Cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton Broth (for most aerobic bacteria)

- Sterile 96-well microtiter plates

- Antibiotic stock solution of known concentration

- Bacterial inoculum, adjusted to ~5 x 10^5 CFU/mL

Method:

- Prepare Drug Dilutions: Serially dilute the antibiotic (typically two-fold dilutions) in broth across the microtiter plate.

- Inoculate: Add an equal volume of the standardized bacterial inoculum to each well. Include growth control (bacteria, no drug) and sterility control (broth only) wells.

- Incubate: Incubate the plate under appropriate conditions (e.g., 35±2°C for 16-20 hours for most bacteria).

- Read Results: The MIC is the lowest drug concentration that completely inhibits visible growth. Compare this value to the interpretive criteria in the CLSI M100 standard to categorize the isolate as Susceptible, Intermediate, or Resistant [26].

Protocol 2: High-Content Analysis for Ex Vivo Drug Sensitivity

This protocol is used for detailed phenotypic profiling of patient-derived cells in response to drug treatment [27] [23].

Materials:

- Patient-derived cells or relevant cell line

- Laminin-coated 384-well CellCarrier plates

- Drug library

- Fixative (e.g., 4% paraformaldehyde)

- Permeabilization buffer (e.g., 0.3% Triton X-100)

- Primary and fluorescently-labeled secondary antibodies

- Nuclear stain (e.g., Hoechst 33342)

- Automated fluorescence microscope (e.g., PerkinElmer Operetta CLS) and analysis software (e.g., Harmony)

Method:

- Cell Seeding: Seed cells onto the coated plate and allow to adhere.

- Drug Treatment: Treat cells with the drug library after 24 hours. Include DMSO vehicle controls.

- Staining and Fixation: After the desired incubation period, fix cells, permeabilize, and block. Incubate with primary antibodies (e.g., anti-c-Met, anti-phospho-c-Met) overnight, followed by fluorescent secondary antibodies and nuclear stain [27].

- Image Acquisition and Analysis: Acquire images using the high-content imaging system. Use the software to automatically quantify multi-parameter readouts such as specific biomarker levels, cell viability (nuclei count), apoptosis (caspase 3/7 activation), and cell motility [27] [23].

Visualizing Pathways and Workflows

Antibiotic Resistance Mechanisms

HCS Drug Sensitivity Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Advanced Drug Sensitivity Research

| Item | Function/Application | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| CLSI M100 Standard | Provides the current, evidence-based breakpoints for interpreting susceptibility test results (MIC values) for aerobic bacteria [21]. | Used as the primary reference for determining if a bacterial isolate is Susceptible, Intermediate, or Resistant to an antibiotic [20] [21]. |

| c-Met Inhibitors (e.g., Cabozantinib, Crizotinib) | Small molecule inhibitors targeting the c-Met receptor tyrosine kinase, used in cancer drug sensitivity studies [27]. | Applied in high-content analysis to identify glioblastoma patients with elevated c-Met levels who may respond to targeted therapy [27]. |

| CDK4/6 Inhibitors (e.g., Abemaciclib) | Inhibitors of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6, used to induce cell cycle arrest in cancer cells. | A drug repurposing screen identified Abemaciclib as having a distinct c-Met-inhibitory function, revealing a new potential application [27]. |

| Lysomotropic Agents & Senolytics (e.g., Fluoxetine, BCL2 inhibitors) | Agents that accumulate in and disrupt lysosomal function, or drugs that selectively eliminate senescent cells [23]. | Used to target cancer stress adaptation pathways, such as therapy-induced senescence, particularly in treatment-resistant mesenchymal neuroblastoma cells [23]. |

| Morbidostat Device | An automated continuous-culture device that dynamically adjusts antibiotic concentration to maintain constant selection pressure [26]. | Enables real-time study of bacterial evolution and the development of drug resistance under controlled, sustained inhibition [26]. |

| Glycerides, C14-26 | 1-Heptadecanoyl-rac-glycerol|MG(17:0)|CAS 5638-14-2 | Research-grade 1-Heptadecanoyl-rac-glycerol, a bioactive monoacylglycerol with demonstrated antimicrobial properties. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

| Hordenine | Hordenine, CAS:62493-39-4, MF:C10H15NO, MW:165.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Advanced Models and Protocols for Enhanced Physiological Relevance

The transition from two-dimensional (2D) to three-dimensional (3D) cell culture represents a paradigm shift in biomedical research. While 2D culture has been a fundamental method for decades, it fails to replicate the complex architecture and cellular interactions of human tissues [29]. In contrast, 3D models like spheroids and organoids mimic the in vivo microenvironment more accurately, leading to more physiologically relevant data for drug discovery and disease modeling [30] [31]. This technical resource center provides essential troubleshooting guidance and protocols to help researchers successfully implement 3D culture technologies.

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Spheroid Formation Issues

Problem: My spheroids are irregularly shaped and lack compactness.

- Solution A: Ensure you are using an appropriate surface treatment. Ultra-low attachment (ULA) plates or poly-HEMA coated plates prevent cell adhesion and promote self-aggregation. Research shows ULA plates typically produce larger, more cohesive spheroids compared to poly-HEMA coatings [32].

- Solution B: Optimize seeding density. Too few cells may not form spheroids, while too many can cause necrotic cores. Test a range from 500-10,000 cells/well in 96- or 384-well formats.

- Solution C: For difficult-to-aggregate cell lines, add low concentrations of extracellular matrix (ECM) components. For instance, adding 2.5% Matrigel to PANC-1 pancreatic cancer cells promotes formation of denser, more uniform spheroids [31].

- Solution D: Centrifuge plates after seeding (300-500 × g for 5-10 minutes) to force cell-cell contact and initiate spheroid formation [31].

Problem: My spheroids show high variability in size and shape between wells.

- Solution A: Use standardized, commercially available U-bottom spheroid microplates rather than homemade coating methods to ensure well-to-well consistency [33].

- Solution B: Prepare single-cell suspensions thoroughly before seeding to avoid clumping.

- Solution C: Maintain consistent medium volume across all wells and minimize evaporation. For hanging drop methods, use humidification chambers with DI water in surrounding wells [34].

Drug Sensitivity Testing Challenges

Problem: Drug responses in my 3D models don't match published in vivo data.

- Solution A: Extend treatment duration. Drugs may require more time to penetrate the 3D structure. Standard 72-hour treatments are common, but some models may need 5-10 days [35] [31].

- Solution B: Account for penetration barriers. The compact architecture of spheroids creates diffusion gradients that limit drug penetration to the core. Consider testing nanocarrier-based delivery systems designed to improve penetration [31].

- Solution C: Verify that your model recapitulates key TME features. Incorporation of stromal cells (e.g., cancer-associated fibroblasts) can significantly alter drug responses, making them more physiologically relevant [31].

Problem: My 3D cultures show unexpectedly high drug resistance compared to 2D.

- Solution A: This may reflect biological reality rather than a technical issue. 3D models naturally develop chemoresistance due to:

- Presence of quiescent cells in the core

- Activation of cell adhesion-mediated drug resistance (CAM-DR)

- Development of hypoxia and acidity gradients

- Solution B: Characterize your model's proliferation gradients using markers like Ki-67, which typically shows higher proliferation in outer layers and quiescence in the core [31].

- Solution C: For cytotoxicity assays, use 3D-optimized ATP-based viability assays that include steps to disrupt spheroids for accurate quantitation [32] [34].

Imaging and Analysis Difficulties

Problem: I can't get clear images of my spheroid interiors.

- Solution A: Use tissue clearing reagents specifically designed for 3D cultures, such as Corning 3D Clear Tissue Clearing Reagent, which improves light penetration without altering morphology [33].

- Solution B: Select appropriate imaging modalities. Avoid standard confocal microscopy for thick samples; instead use light sheet microscopy which provides better penetration for spheroids >200-300μm [31].

- Solution C: Always include a nuclear stain (e.g., DAPI) to assess penetration quality and spheroid architecture [33].

- Solution D: For high-content screening, use U-bottom plates that position spheroids consistently in each well for automated imaging [33].

Problem: Quantitative analysis of 3D cultures is challenging.

- Solution A: Utilize automated image analysis systems (e.g., Incucyte) that can track spheroid growth and morphology over time [31].

- Solution B: For invasion assays, establish consistent quantification methods such as measuring the area of matrix degradation or counting invasive protrusions [32].

- Solution C: When using fluorescence, always subtract background signal from cell-free regions and maintain identical acquisition settings across conditions [32].

Culture Contamination and Viability Problems

Problem: My patient-derived organoids fail to establish or grow slowly.

- Solution A: Optimize matrix composition. Different cell types require specific ECM environments. Systematic testing of Matrigel concentrations (ranging from 50-100%) may be necessary [35] [30].

- Solution B: Use specialized medium formulations containing appropriate niche factors. Patient-derived cancer cells often require customized formulations different from standard cell lines [35] [30].

- Solution C: Process samples quickly after clinical collection—ideally within 1-3 weeks depending on tissue amount and growth rate [35].

Problem: My cultures become contaminated during handling.

- Solution A: For hanging drop platforms, implement thorough sterilization protocols including sonication, 0.1% Pluronic acid treatment for 24 hours, and UV sterilization [34].

- Solution B: Maintain strict humidification to prevent medium evaporation in hanging drops, which can concentrate toxins and stress cells [34].

Essential Methodologies

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Sample Processing: Obtain cancer tissue from surgery or biopsy and process into single-cell suspension using enzymatic digestion.

- Plating: Plate cells in 384-well plates containing Matrigel using automation-compatible methods. Cell density should be optimized for each cell type (typically 500-5,000 cells/well).

- Spheroid Formation: Culture for 3-10 days until compact spheroids form. Monitor growth using live-cell imaging systems.

- Drug Treatment: Add compounds of interest using automated dispensers. Include controls (DMSO vehicle) and reference drugs.

- Viability Assessment: After 72 hours of treatment, measure cell viability directly using luminescence-based assays (e.g., CellTiter-Glo 3D).

- Optional Imaging: Before viability measurement, perform high-content brightfield or fluorescence imaging for morphological analysis.

- Data Analysis: Normalize data to controls, calculate IC50 values, and perform quality control checks.

Timeline: The complete 3D-DSRT protocol typically takes 1-3 weeks from clinical sampling to results, depending on tissue amount, growth rate, and drug numbers.

Workflow Overview:

Detailed Steps:

- Plate Preparation:

- Sonicate hanging drop plates in sterile DI water for 20 minutes

- Wash with running DI water

- Soak in 0.1% Pluronic acid for 24 hours to prevent protein adsorption

- Rinse thoroughly and sterilize with UV light (30-60 minutes per side)

Humidification System:

- Fill 6-well plates with 4-5mL sterile DI water

- Sandwich hanging drop plate between lid and bottom

- Add 800-1000μL sterile DI water around the rim to minimize evaporation

Cell Seeding:

- Prepare single-cell suspensions in serum-free medium

- Seed appropriate cell numbers (typically 1,000-5,000 cells in 40-50μL drops)

- For patient-derived cells, use small cell numbers (as few as 100-500 cells/drop)

Spheroid Formation and Drug Testing:

- Culture for 3-5 days until compact spheroids form

- Add drugs directly to hanging drops

- Monitor morphology and viability over time

Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Materials for 3D Cell Culture Applications

| Product Category | Specific Examples | Key Applications | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Extracellular Matrices | Corning Matrigel Matrix, Collagen I, BME | Organoid culture, Spheroid compaction | Matrigel (∼60% laminin, ∼30% collagen IV) doesn't fully replicate patient tumor ECM (∼90% collagen) [31] |

| Scaffold-Free Platforms | Ultra-Low Attachment (ULA) plates, Poly-HEMA coatings, Hanging drop plates | Simple spheroid formation, High-throughput screening | ULA plates produce larger, more cohesive spheroids than Poly-HEMA [32]; Hanging drops offer high compaction [34] |

| Specialized Media | Defined organoid media, Serum-free formulations | Patient-derived organoids, Cancer stem cell maintenance | Require specific growth factor cocktails; Often need customization for different cell types [30] |

| Analysis Reagents | Corning 3D Clear Tissue Clearing Reagent, ATP-based viability assays, Live-cell stains | 3D imaging, Viability assessment, Long-term monitoring | Tissue clearing enables imaging of spheroid interiors without sectioning [33]; ATP assays require spheroid disruption [32] |

| Cell Culture Supplements | Growth factors (EGF, FGF, Wnt-3A), Noggin, R-spondin | Organoid establishment and maintenance | Essential for stem cell maintenance and differentiation; Concentrations require optimization [30] |

Quantitative Comparison of 3D Culture Platforms

Table: Performance Characteristics of Different 3D Culture Methods

| Platform | Throughput | Cost | Reproducibility | Key Advantages | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hanging Drop | High (384-well) | Low | Moderate | Minimal ECM interference, Easy imaging | Evaporation issues, Manual handling challenging [34] |

| ULA Plates | High (96-/384-well) | Moderate | High | Standardized workflow, Automation compatible | Spheroid size varies by cell line [32] |

| Poly-HEMA | Moderate | Low | Moderate | Cost-effective alternative to ULA | Produces smaller, less cohesive spheroids [32] |

| Matrigel Embedding | Moderate | High | Moderate | Supports complex organoid growth | Batch variability, Complex drug diffusion [35] [31] |

| Hydrogel Systems | Low-Moderate | High | Variable | Tunable mechanical properties | Specialized equipment often needed [29] |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Patient-Derived Models for Personalized Medicine

The pharmaceutical industry is increasingly adopting patient-derived organoids (PDOs) for drug screening and personalized treatment selection [5]. These models maintain the genetic and pathological features of original diseased tissues, enabling:

- Patient-specific drug sensitivity testing: PDOs can be established from patient biopsies and used to identify effective treatments before clinical administration [35] [5].

- Biobanking for drug discovery: Collections of PDOs representing different disease subtypes support the development of targeted therapies [30].

- Clinical trial optimization: PDO platforms can help select patient populations most likely to respond to investigational drugs [5].

Integration with Advanced Technologies

Current research focuses on enhancing 3D models through technological integration:

- Microfluidic systems create more physiologically relevant nutrient and waste gradients while enabling real-time monitoring [29].

- Automated imaging and AI-based analysis platforms enable high-content screening of complex 3D structures [5] [33].

- CRISPR-based gene editing allows precise manipulation of organoids to study disease mechanisms and identify therapeutic targets [30] [5].

The successful transition from 2D to 3D cell culture requires careful consideration of platform selection, protocol optimization, and analytical method adaptation. By addressing the common challenges outlined in this technical resource center, researchers can leverage the full potential of spheroids and organoids to generate more physiologically relevant data for drug discovery and disease modeling. The field continues to evolve rapidly, with ongoing improvements in standardization, automation, and analytical capabilities promising to further enhance the utility of 3D models in biomedical research.

Implementing Patient-Derived Cancer Cells (PDCCs) for Personalized Therapeutic Screening

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common reasons for low PDCC culture initiation success, and how can they be mitigated? Low culture initiation success is a major challenge. This can be due to an extremely low number of obtainable cancer cells, sample quality issues (e.g., low cellularity or massive necrosis), or spontaneous cell death in culture [36] [37]. Mitigation strategies include:

- Rigorous Sample Quality Control: Assess patient tissue for cellularity and necrosis before culture initiation; excluding poor-quality samples can increase success rates [37].

- Optimized Culture Conditions: Use of 3T3-J2 fibroblast feeder layers can support the efficient establishment and long-term stability of 2D PDCC lines from colorectal cancer [37]. For primary hematologic cancer cells, provide essential microenvironmental stimuli (e.g., feeder cells for CLL, or IL-2 and T-cell expansion cocktails for Multiple Myeloma) to prevent spontaneous apoptosis [38].

- Advanced 3D Culture Systems: Employing 3D culture methods like Gelfoam histoculture can facilitate cancer cell migration and growth, providing a more physiologically relevant environment that may improve initiation success [39].

FAQ 2: How can I prevent fibroblast overgrowth in my PDCC cultures? Fibroblast overgrowth is a common problem in standard 2D cultures on plastic or glass. A demonstrated solution is to use a 3D Gelfoam histoculture method. In this system, fragments of patient-derived xenograft (PDX) tumors are placed on Gelfoam, leading to cultures that are essentially all cancer cells without fibroblast contamination [39]. This method has proven effective for establishing PDCCs from colon cancer liver metastases.

FAQ 3: How well do PDCC models retain the original tumor's characteristics? When established with optimized methods, PDCCs can faithfully recapitulate the original tumor. 2D PDCC models have been shown to maintain the genomic landscape of parental tumors with high efficiency [37]. Furthermore, 3D models derived from these cells, such as Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) organotypic cultures, can retain the histological architecture and transcriptomic profiles of the original patient tumor [37]. This preservation of key characteristics is crucial for ensuring the clinical relevance of drug sensitivity testing.

FAQ 4: My drug sensitivity data is highly variable. How can I improve the reliability of my screening results? Variability can arise from technical and biological factors, including heterogeneity in organoid size and shape, or inconsistencies in cell viability [37].

- Standardize Protocols: Follow optimized, standardized drug sensitivity and resistance testing (DSRT) protocols tailored to your cancer type. This includes controlling for seeding density, drug exposure time (typically 72 hours), and using appropriate positive and negative controls on each plate to calculate a Z-prime factor for quality control [38].

- Incorporate Machine Learning: Machine learning (ML) approaches, particularly conformal prediction, can be applied to drug sensitivity prediction. This framework provides a mathematical guarantee of reliability, outputting prediction intervals that contain the true drug response value with a user-specified certainty, thus improving trust in the results for clinical decision-making [40].

FAQ 5: Which culture method (2D vs. 3D) is best for my personalized therapeutic screening? The choice depends on your specific research goals and the trade-offs between physiological relevance and practicality. The table below compares the primary methods:

Table 1: Comparison of Primary PDCC Culture Methods [36]

| Method | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Best Use Cases |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Monolayers | - Simple, easy to manipulate and observe [36] [37]- High proliferation rate [37]- Suitable for large-scale drug screens [36] | - Lacks tumor microenvironment [36]- Loss of tumor heterogeneity and phenotype [36] [37]- Extremely inefficient to establish new lines with traditional methods [37] | - Initial high-throughput drug screening where throughput and cost are primary concerns. |

| 3D Tumor Spheroids | - Better recapitulates 3D architecture and cell-cell interactions than 2D [36] | - Heterogeneous in size and shape [37]- Can lack the complexity of the full tumor microenvironment [36] | - Studying basic tumor biology and drug penetration. |

| 3D Organoids | - Retains genetic and phenotypic heterogeneity of the tumor [36] [37]- Can model patient-specific histology [37] | - Culture success rate can be variable [36]- Rigid matrix (e.g., Matrigel) may limit drug penetration [37]- Heterogeneity in organoid viability [37] | - High-fidelity drug testing and personalized therapy prediction when culture can be established. |

| Gelfoam 3D Histoculture | - Effectively eliminates fibroblast overgrowth [39]- Allows for indefinite passaging potential [39] | - Requires prior establishment of a Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) model [39] | - Generating pure cancer cell cultures for specific tumor types where PDX models are available. |

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Cell Viability in Primary Cultures

Problem: Primary cancer cells die shortly after being placed in culture. Solutions:

- For Hematologic Cancers:

- CLL: Transiently co-culture primary CLL cells with feeder cells prior to drug exposure to prevent spontaneous apoptosis [38].

- Multiple Myeloma: Isolate CD138+ cells and activate them with autologous bone marrow T helper cells in the presence of IL-2 and a T-cell expansion cocktail (anti-CD3/CD28 beads) prior to drug screening [38].

- General Best Practices:

- Use High-Quality Samples: Process fresh tissues quickly or use properly biobanked samples. Note that biobanked samples may have lower baseline viability [38].

- Control Culture Environment: Always include positive (e.g., 100 µM benzethonium chloride) and negative (e.g., 0.1% DMSO) controls on every drug plate to monitor for non-drug induced cell death [38].

Issue 2: Inconsistent Drug Response Readings in Screening Assays

Problem: High variability between replicates in drug sensitivity screens. Solutions:

- Standardize Cell Preparation:

- Use a single-cell suspension by filtering the cells through a 40µm strainer [38].

- For cell lines, screen cells directly after thawing (if viability permits) to reduce variability from long-term culture adaptations. Alternatively, ensure cells are in a consistent growth phase [38].

- Carefully optimize the cell seeding density for each well format to avoid over-confluence or overly sparse wells at the experimental endpoint [38].

- Assay Protocol Rigor:

- Equilibrate assay plates and reagents (e.g., CellTiter-Glo) to room temperature before adding to cells to ensure consistent signal development [38].

- Use a liquid dispenser for uniform cell seeding and reagent addition. Sonicate the dispenser's valves before use to prevent clogging and ensure accuracy [38].

- Cover plates with gas-permeable membranes to limit evaporation during incubation [38].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for PDCC Culture and Screening

| Item | Function / Application | Example / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| 3T3-J2 Fibroblasts | Acts as a feeder layer to support the establishment and growth of 2D PDCC lines from certain cancer types, like colorectal cancer [37]. | Irradiated before use to prevent proliferation [37]. |

| Gelfoam | A scaffold for 3D histoculture that promotes cancer cell growth and migration while suppressing fibroblast overgrowth [39]. | Used for culturing PDX-derived tumor fragments [39]. |

| Matrigel / BME | Basement membrane extract used as a scaffold for 3D organoid culture, providing a more in vivo-like environment [36] [37]. | The relatively rigid matrix may sometimes limit drug penetration in screens [37]. |

| CellTiter-Glo Assay | A luminescent assay to quantify cell viability based on ATP content; commonly used as an endpoint in drug sensitivity screens [38]. | Used for 384-well plate formats; requires luminescence-compatible plates [38]. |

| Air-Liquid Interface (ALI) System | A transwell-based culture system that allows 2D-expanded PDCCs to form 3D organotypic structures that recapitulate original tumor histology [37]. | Useful for creating more physiologically relevant models for validation. |

| Drug Libraries | Collections of compounds used for high-throughput screening to identify patient-specific sensitivities [38]. | Design should be tailored to the cancer type and research question (e.g., targeted therapies, chemotherapies). |

| Nonanoic Acid | Nonanoic Acid, CAS:68937-75-7, MF:C9H18O2, MW:158.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Senna | Senna, CAS:85085-71-8, MF:C42H38O20, MW:862.7 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflows and Data Reliability

The following diagram illustrates a complete workflow for establishing PDCCs and performing reliable drug sensitivity prediction, incorporating machine learning to enhance result trustworthiness.