Oral vs Intravenous Administration: A Comparative Pharmacokinetic Guide for Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the pharmacokinetic principles governing oral and intravenous drug administration, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Oral vs Intravenous Administration: A Comparative Pharmacokinetic Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the pharmacokinetic principles governing oral and intravenous drug administration, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational mechanisms of drug absorption and bioavailability, examines advanced methodological tools like PBPK modeling, addresses key challenges in oral formulation, and presents validation strategies for comparative drug performance. By integrating current research and case studies, this review serves as a strategic resource for optimizing drug delivery systems and informing clinical development decisions.

Core Principles: Understanding Fundamental Pharmacokinetic Differences Between Oral and IV Routes

Absolute bioavailability is a fundamental pharmacokinetic parameter that quantifies the fraction of an orally administered drug that reaches the systemic circulation unchanged relative to intravenous administration. This critical metric reflects the combined impact of absorption, intestinal metabolism, and hepatic first-pass effects on drug disposition. Intravenous administration serves as the gold standard benchmark for these calculations because it delivers the complete drug dose directly into systemic circulation, bypassing absorption barriers and presystemic metabolism. This review synthesizes experimental data and methodological approaches from clinical studies to compare oral versus intravenous administration, providing researchers with a framework for evaluating drug delivery efficiency and optimizing therapeutic formulations.

Absolute bioavailability (F) represents the systemic availability of a drug administered via a non-intravenous route compared to intravenous administration. The calculation of absolute bioavailability relies on comparing the area under the concentration-time curve (AUC) after non-IV administration to the AUC after IV dosing, with appropriate dose normalization [1]. This parameter is crucial in drug development because it reflects the composite effects of incomplete absorption and presystemic metabolism, both of which limit a drug's therapeutic potential.

Intravenous administration provides the ideal reference point for bioavailability calculations because it achieves 100% systemic availability by delivering the drug directly into the circulation [2]. When a drug is administered orally, it must overcome numerous barriers before reaching systemic circulation, including dissolution in the gastrointestinal fluid, permeation through the intestinal mucosa, and metabolism in the gut wall and liver before entering the systemic bloodstream. The extent of this "first-pass effect" varies considerably among drugs and represents a key determinant of oral dosage formulation [2].

Understanding absolute bioavailability enables researchers to make critical decisions about drug developability, dosing regimens, and formulation strategies. Drugs with low absolute bioavailability often exhibit high inter-individual variability, require higher doses to achieve therapeutic effects, and present greater risk of adverse events due to nonlinear pharmacokinetics. Consequently, accurately determining this parameter through well-controlled clinical trials remains an essential component of pharmacokinetic characterization during drug development.

Quantitative Comparison of Absolute Bioavailability Across Drug Classes

The absolute bioavailability of orally administered drugs varies considerably across different therapeutic classes and molecular entities. This variability stems from differences in chemical structure, solubility, permeability, and susceptibility to metabolic enzymes and transport proteins. The following table summarizes absolute bioavailability values for several drugs determined in controlled clinical studies comparing oral and intravenous administration.

Table 1: Absolute Bioavailability Values for Selected Orally Administered Drugs

| Drug | Therapeutic Category | Absolute Bioavailability | Key Factors Influencing Bioavailability | Study Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BI 425809 | Glycine transporter-1 inhibitor | 71.64% | Moderate first-pass metabolism | [1] |

| Ibuprofen | NSAID | 91% | High permeability, minimal first-pass effect | [3] |

| Maraviroc | CCR5 antagonist | 23.1% | Extensive metabolism, P-glycoprotein efflux | [2] |

| FK 506 (Tacrolimus) | Immunosuppressant | 25% (mean) | Variable absorption, bile-dependent | [4] |

| Tramadol | Opioid analgesic | 80% | Moderate first-pass metabolism | [3] |

The data reveal a spectrum of bioavailability values, with ibuprofen demonstrating high bioavailability (91%) due to its favorable permeability and minimal first-pass metabolism [3]. In contrast, maraviroc shows substantially lower bioavailability (23.1%) attributable to its extensive metabolism and involvement of efflux transporters [2]. BI 425809 falls in the intermediate range with approximately 72% bioavailability, suggesting moderate presystemic elimination [1].

These differences in bioavailability have direct clinical implications. Drugs with high bioavailability typically exhibit more predictable dose-response relationships, while those with low or variable bioavailability often require more complex dosing regimens and therapeutic drug monitoring. Furthermore, understanding these differences helps guide formulation strategies, with prodrug approaches often employed for compounds with particularly poor bioavailability.

Experimental Protocols for Determining Absolute Bioavailability

Clinical Study Designs

Determining absolute bioavailability requires carefully controlled clinical trials that compare systemic exposure after oral and intravenous administration. The most common approach involves crossover studies where each participant receives both the oral and intravenous formulations in separate periods with adequate washout intervals. These studies typically employ open-label, single-period, single-arm designs in healthy volunteers under fasting conditions to standardize gastrointestinal variables [1].

For example, in the study of BI 425809, researchers used an innovative IV microtracer approach. Participants received a single oral dose of 25 mg unlabeled BI 425809, followed four hours later (coinciding with expected tmax) by an intravenous microtracer infusion containing 30 μg of [14C]-BI 425809 [1]. This design allowed simultaneous characterization of both routes while minimizing radioactive exposure. The use of radiolabeled IV doses enabled researchers to differentiate between the two administrations through accelerator mass spectrometry, providing precise concentration measurements despite the vastly different doses [1].

Pharmacokinetic Sampling and Analysis

Comprehensive blood sampling protocols are essential for accurate AUC determination. In bioavailability studies, sampling typically begins before dose administration and continues through the complete elimination phase. For instance, in the BI 425809 study, plasma samples for oral drug analysis were collected at 2 hours pre-dose and at 1, 2, 3, 4:05, 6, 8, 12, 24, 72, 120, and 168 hours after administration [1]. For the IV microtracer, additional early time points were included (4:10, 4:15, 4:30 hours) to characterize the distribution phase accurately [1].

The primary pharmacokinetic parameters calculated in these studies include AUC from zero to infinity (AUC0-∞), AUC from zero to the last quantifiable concentration (AUC0-t), and maximum plasma concentration (Cmax). Absolute bioavailability (F) is then calculated using the formula:

F (%) = (AUCoral × DoseIV) / (AUCIV × Doseoral) × 100%

This calculation normalizes for dose differences between administration routes. Statistical comparisons typically use geometric mean ratios with 90% confidence intervals, with bioequivalence generally accepted when these intervals fall within 80-125% [5].

Visualization of Absolute Bioavailability Determination

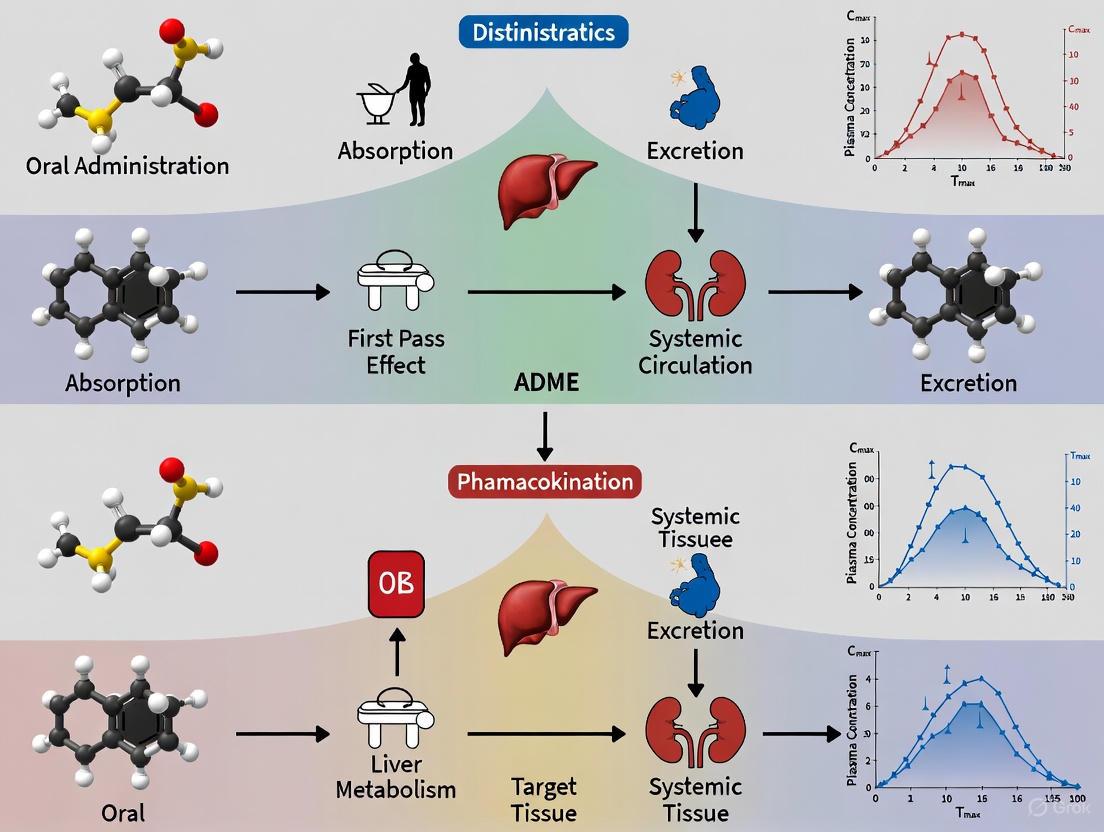

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework and experimental workflow for determining absolute bioavailability in clinical studies.

Determining Absolute Bioavailability: Framework and Workflow

This diagram illustrates the parallel pathways of oral and intravenous drug administration in bioavailability studies. The oral route involves absorption and potential first-pass metabolism before reaching systemic circulation, while intravenous administration provides direct systemic access. The experimental components—study design, pharmacokinetic sampling, and analytical methods—support the generation of AUC values needed for the final bioavailability calculation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Bioavailability Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in Bioavailability Studies | Example from Literature |

|---|---|---|

| Radiolabeled drug compounds ([14C]-labeled) | Enable precise tracking of drug disposition; facilitate IV microtracer approaches | [14C]-BI 425809 used as IV microtracer [1] |

| Validated bioanalytical assays (LC-ESI-MS/MS) | Quantify drug concentrations in biological matrices with high sensitivity and specificity | LC-ESI-MS/MS method for Eperisone quantification with LLOQ of 0.01 ng/mL [6] |

| Accelerator Mass Spectrometry (AMS) | Detect extremely low levels of radiolabeled compounds; essential for microtracer studies | AMS used to measure [14C]-BI 425809 concentrations following IV microtracer dose [1] |

| Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA) Kits | Quantify biologic drugs and protein therapeutics in biological samples | ELISA kit used to measure serum hCG concentrations in bioequivalence study [5] |

| Standardized formulation components | Ensure consistent drug delivery for both oral and intravenous routes | Hydroxy propyl methyl cellulose used in FK 506 capsule formulation [4] |

| 1-Octanol | 1-Octanol, CAS:220713-26-8, MF:C8H18O, MW:130.23 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Oxalacetic acid | Oxalacetic Acid Reagent|For Research Use | High-purity Oxalacetic Acid (OAA) for life science research. A key metabolic cycle intermediate for biochemistry, cell biology, and disease studies. For Research Use Only. Not for human consumption. |

The selection of appropriate research reagents and analytical methodologies is critical for generating reliable bioavailability data. Advanced analytical techniques such as LC-ESI-MS/MS provide the sensitivity and specificity needed to characterize drug concentration-time profiles accurately, especially for drugs administered at low doses or those with extensive distribution [6]. Similarly, the use of radiolabeled compounds coupled with AMS detection enables researchers to conduct innovative study designs like the IV microtracer approach, which provides comprehensive pharmacokinetic information while minimizing participant exposure to radioactivity [1].

The determination of absolute bioavailability using intravenous administration as a benchmark remains an essential component of pharmacokinetic characterization in drug development. The experimental approaches and comparative data presented in this review demonstrate the critical importance of this parameter for understanding drug disposition and optimizing therapeutic regimens. The varying bioavailability values observed across different drug classes highlight the profound impact of physiological processes on drug delivery and underscore the need for rigorous, well-controlled clinical studies to accurately characterize this fundamental pharmacokinetic property. As drug development advances toward more challenging molecular targets, the principles and methodologies of absolute bioavailability determination will continue to provide crucial insights for translating preclinical candidates into effective human therapeutics.

Oral administration is the most common and preferred route for drug delivery due to its non-invasiveness, patient compliance, and cost-effectiveness [7]. However, the journey of an orally administered drug from the gastrointestinal (GI) tract to the systemic circulation is complex, facing numerous physicochemical and biological barriers. Understanding the mechanisms governing this process—passive diffusion, carrier-mediated transport, and efflux pumps—is fundamental to pharmaceutical research and development, particularly in comparative pharmacokinetics where oral bioavailability is benchmarked against the complete systemic availability of intravenous administration [8] [9].

For a drug to be effective after oral administration, it must dissolve in GI fluids, survive the harsh acidic and enzymatic environment, cross the intestinal epithelial membrane, and withstand first-pass metabolism in the liver before reaching systemic circulation [9] [7]. This article provides a comparative guide to the core mechanisms of oral drug absorption, supporting researchers with structured data and experimental protocols to advance drug delivery science.

Core Mechanisms of Oral Drug Absorption

Passive Diffusion: The Dominant Pathway

Definition and Principle: Passive diffusion is the most common mechanism for drug absorption, driven by the concentration gradient across the intestinal membrane according to Fick's law of diffusion [8] [10]. In this process, drug molecules move from a region of high concentration (the GI lumen) to a region of low concentration (the bloodstream) without energy expenditure [11].

Key Determinants:

- Lipid Solubility: The lipoid nature of cell membranes favors the diffusion of lipophilic drugs [11].

- Degree of Ionization: The fraction of un-ionized drug is critical for permeability, governed by the drug's pKa and the environmental pH via the Henderson-Hasselbalch equation [8] [10] [11]. For instance, weakly acidic drugs like aspirin exist primarily in un-ionized, absorbable forms in the stomach, while weak bases are better absorbed in the higher pH of the small intestine [11].

- Molecular Size: Smaller molecules diffuse more rapidly than larger ones [11].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Passive Diffusion

| Parameter | Description | Research Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Driving Force | Concentration gradient | Independent of energy; follows Fick's Law [10] |

| Membrane Route | Transcellular | Requires optimal lipophilicity (Log P) [8] |

| pH Dependency | High (for weak electrolytes) | Requires pH-pKa profiling for predictive modeling [11] |

| Saturability | Non-saturable | Linear kinetics typically observed [8] |

Carrier-Mediated Transport: Facilitated and Active

Definition and Principle: Certain drugs that are structurally similar to endogenous nutrients (e.g., amino acids, sugars, vitamins) utilize specialized carrier proteins embedded in the intestinal membrane [8] [11]. This system is characterized by specificity, saturability, and competitive inhibition.

Types of Carrier Transport:

- Active Transport: Requires energy (ATP) to move drugs against their concentration gradient. This process is selective for drugs mimicking natural metabolites, such as the antihyperglycemic agent metformin, which is transported by the organic cation transporter 1 (OCT1) [8] [12].

- Facilitated Diffusion: Utilizes carrier proteins to move drugs along their concentration gradient without energy expenditure. An example is the transport of vitamin B12 [11].

Table 2: Comparison of Carrier-Mediated Transport Mechanisms

| Characteristic | Active Transport | Facilitated Diffusion |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Requirement | Required (ATP-dependent) [8] | Not required [11] |

| Direction of Transport | Against concentration gradient [8] | Along concentration gradient [11] |

| Saturability | Yes [8] | Yes [8] |

| Example Drug/Transporter | α-Methyldopa [12]; Cephalexin/PEPT1 [12] | Vitamin B12 transport [11] |

Efflux Pumps: P-glycoprotein and Absorption Limitation

Definition and Principle: Efflux transporters act as biological barriers by actively pumping absorbed drugs back into the intestinal lumen, thereby limiting their systemic bioavailability [8] [10]. The most extensively studied efflux pump is P-glycoprotein (P-gp), an ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporter [8] [10].

Functional Impact:

- P-gp is expressed on the apical surface of intestinal epithelial cells and functions as an ATP-dependent efflux pump for a wide range of structurally diverse drugs [8] [10].

- It significantly restricts the absorption of many drugs, including anticancer agents (e.g., paclitaxel), HIV protease inhibitors, and cardiovascular drugs [10]. Research in rats shows that co-administration with a P-gp inhibitor (HM30181) increased paclitaxel's oral bioavailability from 3.4% to 41.3% [10].

The following diagram illustrates the dynamic interplay of these three primary mechanisms in the intestinal epithelial cell.

Experimental Models for Investigating Absorption Mechanisms

Choosing an appropriate experimental model is critical for accurately studying oral drug absorption. The following table compares the primary models used in research, highlighting their advantages and limitations [13].

Table 3: Comparison of Experimental Models for Studying Oral Absorption

| Model Type | Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo (Whole Animal) | Most accurately simulates human physiology; evaluates long-term effects and overall bioavailability [13]. | Long cycle, high cost, ethical concerns, individual variability, difficulty isolating specific pathways [13]. | Preclinical efficacy verification; studying systemic effects on absorption [13]. |

| Ex Vivo/In Situ Tissue | Retains key intestinal structures and functions (barriers, transporters); shorter cycle and lower cost than in vivo [13]. | Lacks systemic factors (blood flow); limited tissue viability; requires specialized operation [13]. | Analyzing nanoparticle-epithelium interactions; screening formulation effects on intestinal barriers [13]. |

| In Vitro (Cell Models) | Low cost, highly controllable, enables molecular-level studies; no animal ethics issues [13]. | Lacks key physiology (mucus, microbiota); simplified cell structure; may overestimate permeability [13]. | Early high-throughput screening; studying endocytic pathways and intracellular transport [13]. |

The Caco-2 Cell Model: The human colon adenocarcinoma cell line (Caco-2) is the most widely used in vitro model. When cultured as a monolayer, these cells spontaneously differentiate to exhibit many characteristics of small intestinal epithelium, including microvilli, tight junctions, and functional expression of various transporters (e.g., P-gp) and metabolic enzymes [13] [12]. Before experimentation, the integrity of the monolayer must be validated, typically by measuring transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) or using marker molecules [13].

Research Reagents and Methodologies

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Absorption Studies

| Reagent / Solution | Function in Research | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cells | A human intestinal epithelial cell line that forms polarized monolayers with microvilli, transporters, and tight junctions, mimicking the intestinal barrier [13] [12]. | Standard model for predicting passive transcellular and carrier-mediated drug permeability [13]. |

| Transport Inhibitors | Chemical compounds used to block specific transport pathways to study their contribution (e.g., P-gp inhibitors like verapamil or GF120918) [13]. | Elucidating the role of efflux pumps; studying the mechanism of carrier-mediated uptake [13]. |

| Simulated Intestinal Fluids (FaSSIF/FeSSIF) | Biorelevant media mimicking the fasted (FaSSIF) and fed (FeSSIF) state intestinal fluid, containing bile salts and phospholipids [14]. | Studying dissolution, supersaturation, and the effect of bile micelles on drug solubility and permeability [14]. |

| Endocytosis Inhibitors | Inhibitors of specific endocytic pathways (e.g., chlorpromazine for clathrin-mediated endocytosis) used to study nanoparticle uptake [13]. | Investigating the cellular internalization mechanisms of nano-formulations [13]. |

| μFLUX System | An in vitro dissolution-permeation flux system that simultaneously monitors drug dissolution and permeation in real-time [14]. | Predicting food effects and the interplay between solubility and permeability [14]. |

| Sulcatone | Sulcatone, CAS:409-02-9, MF:C8H14O, MW:126.20 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Ucf-101 | Ucf-101, CAS:5568-25-2, MF:C27H17N3O5S, MW:495.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: μFLUX for Food Effect Prediction

The μFLUX system is a key tool for evaluating how food impacts the absorption of drugs, particularly those whose absorption is limited by both solubility and epithelial membrane permeation (SL-E drugs) [14].

Methodology:

- Preparation of Donor Solutions: Prepare fasted-state simulated intestinal fluid (FaSSIF) and fed-state simulated intestinal fluid (FeSSIF) according to established biorelevant recipes. These solutions differ primarily in their bile salt and phospholipid content, mimicking in vivo conditions [14].

- Drug Addition: The model drug (e.g., Bosentan, Pranlukast) is introduced to the donor compartment in its solid form or as a suspension.

- Permeation Membrane: A permeation barrier, typically a Caco-2 cell monolayer or an artificial membrane, separates the donor and acceptor compartments.

- Flux Measurement: The system is maintained at 37°C with continuous agitation. Samples are taken from the acceptor compartment over time and analyzed via HPLC or LC-MS/MS to determine the drug flux (JμFLUX), which represents the rate of drug permeation [14].

Data Interpretation:

- For SL-E drugs, even though FeSSIF may drastically increase total drug solubility (Sdissolv) due to bile micelle solubilization, the critical parameter is the free drug concentration (Sdissolv,u), which often remains unchanged. Consequently, the observed JμFLUX may show little enhancement despite a large increase in total dissolved drug, correctly predicting a weak food effect [14].

- This experimental observation validates the theoretical framework that for SL-E drugs, an increase in solubility by bile micelles is counterbalanced by a decrease in effective permeability [14].

The workflow for this integrated experimental and theoretical approach is summarized below.

The absorption of oral drugs is a multifaceted process governed primarily by passive diffusion, carrier-mediated transport, and efflux pumps. A deep understanding of these mechanisms is indispensable for rational drug design and formulation strategies aimed at overcoming poor bioavailability. The interplay of these processes determines the fraction of the administered dose that ultimately reaches the systemic circulation, a key parameter in comparative pharmacokinetics against intravenous administration.

Advanced experimental models and biorelevant tools, such as the Caco-2 cell system and the μFLUX apparatus, provide critical insights into these mechanisms. By integrating theoretical frameworks like FaRLS with robust experimental data, researchers can more accurately predict in vivo performance, including the impact of food, leading to the development of more effective and reliable oral drug products.

First-pass metabolism, also known as the first-pass effect, is a fundamental pharmacokinetic phenomenon wherein a drug undergoes pre-systemic metabolism at specific locations in the body before reaching the systemic circulation or its site of action [15]. This process substantially decreases the concentration of the active drug, thereby limiting its therapeutic potential when administered via the oral route. While the liver serves as the primary site for first-pass metabolism, other metabolically active tissues including the gastrointestinal lumen, gastrointestinal wall, and lungs also contribute to this effect [15] [16].

The clinical impact of first-pass metabolism is profound, as it represents one of the most significant barriers to oral drug bioavailability. For drug development scientists and researchers, understanding the mechanisms and extent of first-pass elimination is crucial for optimizing drug delivery systems and dosing regimens. The variability of first-pass metabolism among individuals—influenced by factors such as age, gender, genetic polymorphisms, and disease states—further complicates the prediction of in vivo drug performance from in vitro models [15] [17]. This article examines the experimental evidence quantifying first-pass effects and compares the pharmacokinetic profiles of drugs administered via oral versus intravenous routes, providing researchers with methodological frameworks for studying this critical pharmacological barrier.

Physiological Mechanisms and Metabolic Pathways

The first-pass effect encompasses several sequential barriers that orally administered drugs must navigate before entering the systemic circulation. The process begins in the gut lumen, where enzymes and the acidic environment can degrade certain pharmaceutical compounds [16]. Subsequently, drugs face metabolic challenges within the enterocytes of the intestinal wall, which contain significant concentrations of cytochrome P450 enzymes, particularly CYP3A4, and phase II conjugation enzymes [16] [18].

After surviving intestinal metabolism, drugs are transported via the portal vein to the liver, where they encounter highly efficient enzyme systems capable of extensive biotransformation [15] [17]. The hepatic metabolism involves Phase I reactions (oxidation, reduction, hydrolysis) primarily mediated by cytochrome P450 enzymes, and Phase II reactions (conjugation with glucuronide, sulfate, or other moieties) that typically render compounds more water-soluble for excretion [17]. The interplay between these metabolic pathways determines the extent to which a drug survives first-pass metabolism to produce its therapeutic effect.

The following diagram illustrates the sequential metabolic barriers that constitute the first-pass effect for orally administered drugs:

Quantitative Comparison: Oral vs. Intravenous Administration

Direct pharmacokinetic comparisons between oral and intravenous administration provide the most compelling evidence of first-pass metabolism. The table below summarizes key experimental findings from clinical studies that quantify these differences across multiple therapeutic agents:

Table 1: Pharmacokinetic Comparison of Oral versus Intravenous Drug Administration

| Drug | Study Details | Key Pharmacokinetic Findings | Bioavailability Impact |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chloramphenicol [19] | 14 infants with H. influenzae meningitis; 100 mg/kg/day every 6 hours | - IV: Mean peak serum level: 15.0 μg/ml at 45 min- Oral: Mean peak serum level: 18.5 μg/ml at 2-3 hours- Serum half-life: 4.0 hours (IV) vs. 6.5 hours (oral) | Extended half-life but delayed Tmax with oral administration |

| Busulfan [20] | 40 patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation | - IV: Median AUC: 1244.8 μMol·min- Oral: Median AUC: 1174 μMol·min- Extreme interpatient variability in oral pharmacokinetics | Similar AUC but higher variability with oral administration |

| Diazepam [15] | Pediatric patients with febrile seizures | Active metabolites (desmethyldiazepam, oxazepam) with similar physiological effects | Significant first-pass metabolism with active metabolites |

| Nitroglycerin [15] | Angina treatment | Rapid relief via sublingual administration bypassing first-pass effect | Complete avoidance of first-pass metabolism with alternative routes |

| Dextromethorphan [15] | Pseudobulbar affect treatment | Coadministration with quinidine inhibits first-pass metabolism | 45-50% increase in systemic exposure with metabolic inhibition |

The data demonstrate that first-pass metabolism not only reduces drug bioavailability but can also significantly alter other pharmacokinetic parameters, including time to peak concentration (Tmax) and elimination half-life. These changes have profound implications for dosing regimen design and therapeutic monitoring protocols.

Experimental Models for Studying First-Pass Metabolism

Research into first-pass metabolism employs a hierarchy of experimental models, each with distinct advantages and limitations. The following table systematizes the primary models used in absorption and first-pass metabolism research:

Table 2: Experimental Models for First-Pass Metabolism Research

| Model Type | Advantages | Limitations | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| In Vivo (Whole Animal) [13] | - Most accurately simulates human physiology- Evaluates long-term effects and systemic bioavailability- Suitable for preclinical verification | - Long experimental cycles and high costs- Individual variability reduces reproducibility- Ethical considerations- Difficulty isolating specific pathways | - Studying systemic absorption effects- Long-term bioavailability studies- Preclinical efficacy verification |

| Ex Vivo/In Situ Intestinal Models [13] | - Retains key intestinal structures and functions- Less complex than whole animal models- Shorter experimental cycles- Direct observation of formulation behavior | - Lacks systemic factors (blood flow, hormones)- Limited tissue viability (hours to days)- Requires specialized isolation techniques- Microenvironment alterations may distort results | - Analyzing local intestinal absorption mechanisms- Screening formulation effects on barriers- Comparing segmental absorption differences |

| Cell Models (Caco-2, MDCK) [13] | - Low cost, easy standardization, high controllability- Enables molecular-level mechanism studies- No animal ethical issues- High-throughput screening capability | - Lacks key physiological components (mucus, microbiota)- Simplified cell structure not fully representative- Cannot simulate multi-organ interactions- May overestimate permeability | - Early formulation screening- Molecular-level mechanism studies- Transporter-mediated uptake investigations |

The workflow for employing these models in first-pass metabolism studies typically follows a sequential approach from simple screening to complex validation:

Methodological Approaches for Investigating First-Pass Effects

Clinical Pharmacokinetic Study Protocol

The standard methodology for quantifying first-pass metabolism in human subjects involves a crossover design comparing oral and intravenous administration [19]:

Subject Selection: Recruit appropriate patient populations or healthy volunteers with consideration for genetic profiling of metabolic enzymes

Dosing Protocol:

- Intravenous administration with precise dosing and infusion rate documentation

- Oral administration after an appropriate washout period, typically with standardization of fasting/fed state

Sample Collection:

- Serial blood sampling at predetermined time points (e.g., pre-dose, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8, 12, 24 hours post-dose)

- Plasma separation via centrifugation and storage at -80°C until analysis

Bioanalytical Methods:

- Utilization of validated LC-MS/MS methods for drug and metabolite quantification

- Implementation of stable isotope-labeled internal standards for precision

Data Analysis:

- Non-compartmental analysis to determine AUC, Cmax, Tmax, and t1/2

- Calculation of absolute bioavailability: F = (AUCoral × DoseIV) / (AUCIV × Doseoral)

- Assessment of metabolite-to-parent drug ratios to evaluate metabolic pathways

Advanced Research Techniques

Emerging technologies are addressing the limitations of traditional models in studying first-pass metabolism [13]:

- Microphysiological Systems: Organ-on-a-chip platforms that simulate human gastrointestinal and hepatic tissues with fluidic connectivity

- CRISPR-Cas9 Modified Cell Lines: Genetically engineered intestinal and hepatic cells with specific overexpression or knockout of metabolic enzymes and transporters

- In Vivo Subcellular High-Resolution Imaging: Advanced microscopy techniques to track drug distribution and metabolism in real-time at the subcellular level

- Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling: Computational approaches that integrate in vitro metabolism data with physiological parameters to predict first-pass extraction

Research Reagent Solutions for First-Pass Metabolism Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for First-Pass Metabolism Investigations

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Cell Models [13] | Caco-2 cells, MDCK cells, Primary hepatocytes, HuTu-80, HepG2 | Intestinal permeability screening, hepatic metabolism studies, transporter characterization |

| Enzyme Inhibitors [15] [17] | Ketoconazole (CYP3A4), Quinidine (CYP2D6), Sulfaphenazole (CYP2C9), BNPP (esterases) | Metabolic pathway identification, enzyme contribution quantification, drug-interaction studies |

| Transport Inhibitors [18] | Verapamil (P-gp), MK-571 (MRP2), Ko143 (BCRP) | Transporter efflux assessment, absorption enhancement strategies |

| Specialized Polymers [21] | HPMC, HPMCAS, PVP, PVP-VA, PEG | Amorphous solid dispersions, solubility enhancement, crystallization inhibition |

| Permeation Enhancers [18] | Sodium caprate, Chitosan, Medium-chain fatty acids, Labrasol | Paracellular pathway modulation, tight junction regulation, absorption improvement |

| Analytical Standards [19] [20] | Deuterated internal standards, metabolite standards, certified reference materials | Bioanalytical method development, metabolite identification and quantification |

Strategies to Overcome First-Pass Metabolic Barriers

Multiple formulation and chemical strategies have been successfully employed to mitigate the impact of first-pass metabolism:

Formulation Approaches

Prodrug Design: Chemical modification of drug molecules to create precursors that bypass first-pass metabolism but convert to active forms in systemic circulation [16]. Examples include ester prodrugs that are resistant to hepatic hydrolysis but undergo plasma enzyme conversion.

Lymphatic Targeting: Utilization of lipid-based formulations including self-emulsifying drug delivery systems (SEDDS) that promote intestinal lymphatic transport, thereby bypassing hepatic first-pass metabolism [18].

Nanoparticle Systems: Engineered nanocarriers that protect drugs from metabolic degradation and enhance absorption through specialized pathways, including M-cell transport in Peyer's patches [13] [21].

Permeation Enhancers: Excipients that temporarily increase intestinal permeability by modulating tight junctions or fluidizing epithelial cell membranes [18].

Alternative Administration Routes

Sublingual and Buccal Delivery: Administration through the oral mucosa directly into the systemic circulation, completely avoiding first-pass metabolism [15] [16].

Rectal Administration: Partial avoidance of first-pass metabolism through hemorrhoidal vein drainage directly into the inferior vena cava [15].

Transdermal Systems: Continuous delivery through the skin into systemic circulation, bypassing gastrointestinal and hepatic metabolism [16].

First-pass metabolism remains a critical determinant of oral drug bioavailability with profound implications for drug development and clinical practice. The experimental evidence clearly demonstrates that first-pass effects can substantially reduce systemic drug exposure, alter metabolic profiles, and increase interpatient variability. For researchers engaged in drug development, a multifaceted approach combining advanced in vitro models, preclinical validation, and strategic formulation design offers the most promising path to overcoming these metabolic barriers.

The continuing evolution of research methodologies—including microphysiological systems, targeted genomic editing, and sophisticated computational modeling—promises to enhance our predictive capabilities regarding first-pass metabolism. By systematically applying these tools and strategies, drug development scientists can more effectively navigate the challenges posed by first-pass effects and optimize the therapeutic potential of novel pharmaceutical compounds.

Drug absorption describes the transportation of an unmetabolized drug from its site of administration into the systemic circulation [8]. This process is the most fundamental principle in pharmacokinetics and is the critical first step determining whether an active pharmaceutical ingredient will reach its target site of action. The most common mechanisms for this transport include passive diffusion, where drug molecules move according to a concentration gradient from areas of high concentration to low concentration, and carrier-mediated membrane transport, which includes active transport and facilitated diffusion [8]. The complex journey of a drug from its administered form to systemic circulation is influenced by a confluence of factors that can be broadly categorized as drug-specific (physicochemical and pharmaceutical variables) and patient-specific (physiological variables) [8].

The route of administration profoundly impacts the absorption process and the ultimate bioavailability of a drug, defined as the rate and extent of its absorption [8]. Generally, the order of bioavailability among different routes of administration, ranked from highest to lowest, is parenteral, rectal, oral, and topical [8]. Intravenous (IV) administration achieves 100% bioavailability because the drug is introduced directly into the bloodstream, completely bypassing the absorption process [8] [22]. In contrast, oral administration requires the drug to survive the gastrointestinal (GI) tract environment, cross the intestinal epithelium, and withstand first-pass metabolism in the liver before reaching systemic circulation, which often results in reduced and more variable bioavailability [11] [22]. Understanding the interplay between a drug's physicochemical properties and the biological barriers it encounters is essential for predicting and optimizing its therapeutic performance.

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS): A Framework for Predicting Absorption

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) is a fundamental scientific framework that prognosticates the in vivo absorption performance of orally administered drugs based on two key physicochemical properties: solubility and intestinal permeability [23]. Developed for human drug application, this system categorizes drug substances into one of four classes, which helps identify the rate-limiting step in the absorption process and guides formulation strategies [23] [24].

The Four BCS Classes

BCS Class I: High Solubility, High Permeability These drugs are generally very well-absorbed because they readily dissolve in the GI fluids and easily cross the intestinal membrane. Their absorption is typically rapid and complete, and dissolution rate often dictates the absorption speed [23]. For example, a study analyzing drugs on the World Health Organization's Essential Medicines list found that 84% of the classifiable drugs belonged to BCS Class I [24].

BCS Class II: Low Solubility, High Permeability For these compounds, absorption is dissolution rate-limited. Although the drug has high permeability once in solution, its poor solubility slows the dissolution process, thereby restricting the overall rate and sometimes the extent of absorption. Formulation strategies for BCS Class II drugs often focus on enhancing solubility and dissolution, such as through particle size reduction or the use of solubilizing agents [23].

BCS Class III: High Solubility, Low Permeability The absorption of BCS Class III drugs is permeability rate-limited. While these drugs dissolve readily in the GI tract, their ability to cross the intestinal epithelium is low. Consequently, their absorption is highly dependent on the permeability barrier rather than formulation factors affecting dissolution [23].

BCS Class IV: Low Solubility, Low Permeability Drugs in this class suffer from both poor solubility and poor permeability, leading to significant challenges in achieving adequate and consistent oral bioavailability. They often exhibit very poor and highly variable absorption [23].

Table 1: Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) Drug Categories

| BCS Class | Solubility | Permeability | Absorption Characteristic | Rate-Limiting Step |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | High | High | Very well-absorbed | Gastric emptying / Dissolution rate |

| Class II | Low | High | Dissolution-limited absorption | Dissolution rate |

| Class III | High | Low | Permeability-limited absorption | Intestinal permeability |

| Class IV | Low | Low | Poor and variable absorption | Combination of dissolution and permeability |

Defining High Solubility and High Permeability

The BCS provides specific, standardized criteria for classifying a drug as "highly soluble" or "highly permeable". A drug is considered highly soluble when the highest marketed dose strength is soluble in 250 mL of aqueous media over a pH range of 1.0 to 7.5 at 37°C [23]. This volume is derived from typical human gastric fluid volume. A drug is classified as highly permeable when the extent of intestinal absorption in humans is determined to be 90% or more of an administered dose, based on a mass balance study or in comparison to an intravenous reference dose [23].

The following diagram illustrates the logical decision process for classifying a drug according to the BCS framework:

Experimental Protocols for Key Assays

Determining a drug's BCS classification requires robust and standardized experimental methods to accurately measure its solubility and permeability.

Solubility and Dissolution Assessment

The solubility measurement for BCS classification is dose-dependent, not purely intrinsic. The experimental protocol involves:

- Apparatus: Shaking water bath or equivalent system maintained at 37°C ± 0.5°C.

- Buffer Preparation: Prepare aqueous media within the pH range of 1.0 to 7.5 (e.g., 0.1 N HCl or pH 7.5 phosphate buffer). The pH of the solution should be verified after the addition of the drug substance.

- Procedure: An excess of the drug substance is added to a measured volume of the buffer (typically 250 mL is the benchmark volume for human BCS). The mixtures are shaken for a sufficient time to reach equilibrium (often up to 24 hours).

- Analysis: The solutions are then centrifuged or filtered to remove undissolved material, and the concentration of the drug in the supernatant or filtrate is quantified using a validated stability-indicating assay, such as High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) with UV detection [23].

- Calculation: The dose number (Do), a key parameter, is calculated as the ratio of the drug dose to the product of its solubility and a standard volume (250 mL for humans). A Do value greater than 1 classifies the drug as poorly soluble [23].

Permeability Assessment

While human absorption data is the gold standard for permeability classification, several in vitro and in vivo models are used during drug development:

- In Vitro Cell-Based Models: The Caco-2 (human colon adenocarcinoma) cell line is a widely accepted model for predicting human intestinal permeability. Cells are cultured on semi-permeable membranes until they differentiate into an intestinal epithelium-like monolayer. The drug is added to the donor compartment (apical side for simulating intestinal lumen), and samples are taken from the receiver compartment (basolateral side) over time to determine the apparent permeability coefficient (Papp). A good correlation has been shown between permeability coefficients in Caco-2 cells and the fraction of drug absorbed in humans [24].

- In Vivo Pharmacokinetic Studies: Absolute bioavailability (F) studies provide the most direct measure of absorption. In these studies, the exposure (AUC) of a drug after oral administration is compared to its exposure after intravenous administration in the same subject. An absolute bioavailability of 90% or higher is considered evidence of high permeability [23]. For instance, a study comparing intravenous and oral chloramphenicol in infants with meningitis provided key pharmacokinetic data, including half-life and bioavailability, that illuminated its absorption characteristics [19].

Table 2: Experimental Models for Assessing BCS Criteria

| Parameter | Primary Method | Key Experimental System | Classification Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility | Equilibrium Solubility | Shake-flask method in pH 1–7.5 buffers at 37°C | Dose number (Do) ≤ 1 in 250 mL |

| Permeability (In Vitro) | Cell Monolayer Transport | Caco-2 cell model | Papp correlates with ≥90% absorption |

| Permeability (In Vivo) | Mass Balance / Bioavailability | Human pharmacokinetic study | Absolute bioavailability (F) ≥ 90% |

Advanced Considerations and the Role of Precipitation

Beyond the foundational solubility and permeability, other complex phenomena can govern oral absorption. For weakly basic drugs, which represent a significant portion of modern pharmaceuticals, precipitation in the gastrointestinal tract is a critical parameter [25] [26]. These drugs often exhibit high solubility in the acidic environment of the stomach but can precipitate upon entering the more neutral pH of the small intestine, where the majority of absorption occurs. This precipitation can significantly reduce the concentration of drug available for absorption, thereby limiting bioavailability.

Recent research has focused on developing predictive in vitro tools to model this phenomenon. For example, one study developed a miniaturized precipitation assay (µPA) to screen drug candidates during discovery. The results indicated a clear relationship between the extent of precipitation observed in vitro and the fraction of drug absorbed in vivo, highlighting precipitation as a key parameter for early oral absorption predictions [25] [26]. This necessitates an integrated experimental approach that considers solubility, permeability, and precipitation kinetics to build a comprehensive absorption profile, especially for BCS Class II bases.

The following workflow summarizes the integrated experimental strategy for predicting oral drug absorption, incorporating precipitation assessment for basic drugs:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The experimental characterization of a drug's absorption potential relies on a suite of specialized reagents, cell lines, and laboratory equipment.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Materials for Absorption Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Caco-2 Cell Line | In vitro model of human intestinal epithelium for permeability screening. | Permeability classification, transport mechanism studies. |

| Transwell Plates | Permeable supports for growing cell monolayers for transport studies. | Caco-2 assays; measuring apparent permeability (Papp). |

| Simulated GI Fluids | (e.g., FaSSGF, FaSSIF) Biorelevant media mimicking fasting-state stomach and intestinal composition. | Solubility and dissolution testing under physiologically relevant conditions. |

| HPLC-UV/MS Systems | High-performance liquid chromatography for quantifying drug concentrations in solubility, dissolution, and permeability samples. | Analytical quantification in all key assays. |

| PAMPA Kit | Parallel Artificial Membrane Permeability Assay for high-throughput passive permeability screening. | Early-stage, high-throughput permeability ranking. |

| Diethyltoluamide | N,N-Diethyl-2-methylbenzamide | N,N-Diethyl-2-methylbenzamide for research applications. This active agent is for Research Use Only. Not for diagnostic, therapeutic, or personal use. |

| Resveratrol | Resveratrol, CAS:133294-37-8, MF:C14H12O3, MW:228.24 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The framework established by the Biopharmaceutics Classification System, grounded in the fundamental physicochemical properties of solubility and permeability, provides an indispensable tool for rational drug development. It allows scientists to predict absorption challenges, design appropriate formulations, and understand the implications of in vitro data on in vivo performance. While the BCS was developed for human drugs, its principles are universally applicable, though specific criteria (like the volume for solubility assessment) may require adaptation for veterinary species [23]. The continued evolution of this field, with the integration of more complex phenomena like precipitation and the development of advanced in vitro tools, ensures that the BCS will remain a cornerstone for optimizing the oral bioavailability of new therapeutic agents and for making informed decisions in a regulatory context, including the possibility of biowaivers for BCS Class I drugs [24].

For drug development professionals and clinical pharmacologists, the oral route remains the most common, yet notoriously variable, pathway for drug administration. The fundamental thesis of comparative pharmacokinetics (PK) of oral versus intravenous (IV) administration rests on a simple principle: while IV delivery provides direct access to systemic circulation, oral drugs must navigate a complex gastrointestinal (GI) environment where physiological variables profoundly influence their journey into the bloodstream [27] [8]. This journey—dictated by gastric emptying, intestinal pH, and food interactions—determines the critical pharmacokinetic parameters of bioavailability, time to maximum concentration (Tmax), and overall exposure (AUC). Understanding these variables is not merely academic; it directly informs drug formulation, dosing regimen recommendations, and the interpretation of bioequivalence studies [27] [15]. This guide objectively compares the performance of orally administered drugs against the IV benchmark by examining how core physiological factors alter oral PK, supported by experimental data and methodologies.

Core Physiological Variables Governing Oral Drug Absorption

Gastric Emptying and Intestinal Transit

Gastric emptying is often the rate-limiting step for drug absorption [27]. The transfer of stomach contents into the duodenum is regulated by the migrating motor complex (MMC) during fasting and exhibits a different pattern in the postprandial state [27] [28].

- Fasted State: The MMC cycle, which includes propagating contractions, results in a highly variable gastric emptying time [27].

- Fed State: A high-calorie or high-fat meal can significantly delay gastric emptying, prolonging the time a drug remains in the stomach [27]. This delay directly impacts the Tmax of orally administered drugs.

Small Intestinal Transit Time is typically more consistent, averaging 2-6 hours, and is less influenced by food [29] [28]. This transit determines the time available for dissolution and permeation across the intestinal wall.

Advanced techniques for measuring transit times include:

- Wireless Motility Capsule (WMC): An ingestible, indigestible capsule that measures pH, pressure, and temperature to determine regional transit times [29]. Gastric emptying is marked by an abrupt pH rise as the capsule moves from the acidic stomach to the alkaline duodenum.

- Magnet Tracking System (MTS-1): Tracks an ingested magnet via an external sensor matrix, providing high-resolution data on pill position and contraction frequencies [28]. Pyloric passage is identified by the cessation of the stomach's ~3 contractions/minute pattern and the onset of the small intestine's 8-11 contractions/minute frequency.

Gastrointestinal pH

The pH environment varies significantly along the GI tract and is a major determinant of a drug's dissolution and solubility, particularly for ionizable compounds [27] [30] [8].

Table 1: Physiological pH Ranges in the Gastrointestinal Tract

| GI Segment | Fasted State pH | Fed State pH | Impact on Drug Absorption |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stomach | 1.0 - 3.0 [30] | Transiently rises to ~5.0 [27] | Affects solubility of weak acids/bases; stability of acid-labile drugs. |

| Duodenum | ~6.0 [27] | 6.0 - 8.0 [30] | Primary site for dissolution and absorption for many drugs. |

| Small Intestine | 6.0 - 8.0 [27] [30] | 6.0 - 8.0 [30] | Large surface area favors absorption; bile salts enhance solubility. |

For weakly basic drugs, the elevated gastric pH under fed conditions can reduce dissolution, while for weakly acidic drugs, solubility may increase [30]. Furthermore, acid-reducing agents (ARAs) like proton pump inhibitors can perpetuate these pH-mediated drug-drug interactions [30].

The Impact of Food

Food ingestion triggers a cascade of physiological changes: delayed gastric emptying, increased bile secretion, changes in splanchnic blood flow, and fluctuations in luminal pH [27]. These changes can lead to positive, negative, or neutral food effects on drug absorption.

- Positive Food Effects: Increased bioavailability (AUC) can result from:

- Negative Food Effects: Decreased bioavailability can occur due to:

- Binding or complexation of the drug with food components.

- Instability of the drug in the altered GI environment.

- Delayed Tmax, which may be critical for drugs requiring rapid onset, such as analgesics.

The Biopharmaceutics Classification System (BCS) provides a framework for predicting food effects based on a drug's solubility and permeability [27]. BCS Class II drugs (low solubility, high permeability) are particularly susceptible to food effects, as their absorption is solubility-limited.

Comparative Pharmacokinetics: Oral vs. Intravenous Administration

The intravenous route serves as the gold standard for bioavailability, defined as 100%, because the entire dose enters the systemic circulation directly [8]. In contrast, oral bioavailability (F) is a fraction determined by the extent of absorption and first-pass metabolism.

The relationship is defined by: F = (AUCoral / AUCIV) × (DoseIV / Doseoral)

Table 2: Experimental PK Data from an Ibuprofen/Tramadol Study [31]

| Drug / Analyte | Route | Absolute Bioavailability (F) | Key PK Parameter Observations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen | Oral | 91% | Equivalent AUC for oral and IV administration. |

| Tramadol | Oral | 80% | IV administration produced higher Cmax of parent drug. |

| O-desmethyl-Tramadol (M1) | Oral (as metabolite) | N/A | IV administration of parent Tramadol resulted in lower M1 metabolite exposure than oral route. |

This data illustrates that even with high oral bioavailability, the rate of absorption and metabolite profile can differ significantly between routes, influenced by first-pass metabolism.

The First-Pass Effect

Orally administered drugs are absorbed through the GI tract and enter the hepatic portal vein, passing through the liver before reaching the systemic circulation [15] [16]. Pre-systemic metabolism in the gut wall and liver—the first-pass effect—can substantially reduce the bioavailability of the active drug [15]. Drugs like morphine and propranolol undergo significant first-pass metabolism, necessitating much higher oral than IV doses [15]. This effect exhibits marked inter-individual variability due to differences in enzyme expression (e.g., Cytochrome P450, particularly CYP3A4) and liver function [15] [16].

Diagram 1: First-Pass Effect Pathway.

Methodologies for Assessing Physiological Variables

Experimental Protocols for Transit and Motility

Wireless Motility Capsule (WMC) Protocol [29]:

- Patient Preparation: Overnight fast. Discontinuation of prokinetics, laxatives, narcotics, and anticholinergics 3-7 days prior.

- Test Meal & Ingestion: Ingest a standardized nutrient bar (e.g., SmartBar) and 50 mL water, followed by the activated WMC.

- Post-Ingestion: No food or drink for 6 hours. Patient wears a data receiver for 3-5 days, logging meals, sleep, and bowel movements.

- Data Analysis: Software (e.g., MotiliGI) uses pH, pressure, and temperature data to identify landmarks.

- Gastric Emptying Time (GET): Time from ingestion to an abrupt, sustained pH rise (>3 units).

- Small Bowel Transit Time (SBTT): Time from gastric emptying to an abrupt pH drop (>1 unit) marking entry into the cecum.

- Whole Gut Transit Time (WGTT): Time from ingestion to a temperature drop or signal loss, indicating excretion.

Magnet Tracking System (MTS-1) Protocol [28]:

- Ingestion: A small magnetic pill is swallowed.

- Tracking: An external 4x4 matrix of magnetic field sensors, placed over the abdomen, tracks the pill's position and orientation at 10 Hz.

- Data Analysis: Custom software (e.g., MTS_Record) displays real-time data. Pyloric passage is identified by a change in contraction frequency from ~3/min (stomach) to 8-11/min (small intestine). Ileocecal passage is marked by cessation of the small intestinal frequency pattern.

Assessing Food Effects: Clinical FEED Studies

Regulatory-grade food-effect studies follow a standardized design [27]:

- Design: Single-dose, randomized, two-period (fed vs. fasted), crossover study.

- Fasted State: Overnight fast of at least 10 hours before dosing. No food for at least 4 hours post-dose.

- Fed State: Overnight fast followed by a high-fat, high-calorie meal (e.g., ~800-1000 calories) consumed 30 minutes before dosing.

- PK Analysis: Blood sampling over time to determine AUC, Cmax, and Tmax. A statistical comparison (90% confidence intervals) indicates the presence of a significant food effect.

Diagram 2: Food-Effect Study Workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials and Tools for GI Transit and Absorption Studies

| Research Tool / Reagent | Function & Application in PK Research |

|---|---|

| Wireless Motility Capsule (WMC) | Provides a non-invasive, radiation-free method for assessing regional and whole gut transit times (GET, SBTT, WGTT) via pH, pressure, and temperature sensors [29]. |

| Magnet Tracking System (MTS-1) | Offers high-resolution tracking of an ingested magnet's position and orientation to determine transit times and contractile frequencies [28]. |

| High-Fat/High-Calorie Meal | Standardized meal per FDA guidance used in food-effect (FEED) studies to create a maximally disruptive physiological state for evaluating food's impact on drug absorption [27]. |

| Simulated Intestinal Fluids | Biorelevant media (e.g., FaSSIF/FeSSIF) that mimic the fasted and fed state composition of human intestinal fluid for in vitro dissolution and solubility testing [32]. |

| PBPK Modeling Software | Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) platforms simulate drug PK under various conditions, integrating drug properties and physiological data to predict food effects and absorption [27] [33]. |

| Capsule Endoscopy (PillCam) | Allows for direct visualization of GI transit and mucosal status; often used as a validation tool for other transit measurement techniques like MTS-1 [28]. |

| Isoalantolactone | Isoalantolactone, CAS:107439-69-0, MF:C15H20O2, MW:232.32 g/mol |

| Stictic acid | Stictic acid, CAS:56614-93-8, MF:C19H14O9, MW:386.3 g/mol |

Advanced Tools and Techniques: PBPK Modeling and Study Designs for Route Comparison

Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling for Predicting Oral Absorption

Predicting oral drug absorption is a critical challenge in drug development, complicated by dynamic physiological processes in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract and complex drug-specific properties. Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling has emerged as a powerful mechanistic tool to simulate and predict the oral absorption process, integrating physiological parameters with drug-specific data to forecast pharmacokinetic profiles [34]. Unlike classical compartmental models that simplify absorption as a first-order process, PBPK models mechanistically represent the GI tract as a series of compartments, each with distinct physiological characteristics that influence drug dissolution, permeation, and metabolism [34]. This approach provides a significant advantage over static prediction methods by enabling dynamic simulation of concentration-time profiles and accounting for complex interplays between drug properties and physiological variables [35].

Within the broader context of comparative pharmacokinetics research, PBPK modeling offers unique insights into the fundamental differences between oral and intravenous administration. While intravenous administration delivers drug directly into systemic circulation, oral absorption involves sequential processes including dissolution, GI transit, permeation, and first-pass metabolism that collectively determine bioavailability [34]. PBPK models quantitatively integrate these processes, allowing researchers to deconvolute the specific factors limiting oral bioavailability and systematically compare exposure profiles across different administration routes.

Comparative Analysis of PBPK Modeling Platforms

PBPK modeling platforms provide specialized software environments that combine technical computational infrastructure with physiological content libraries to support model development and simulation [36]. The leading platforms—including Simcyp Simulator, GastroPlus, and PK-Sim—have evolved to incorporate increasingly sophisticated absorption models that account for regional differences in GI physiology, fluid composition, and transit times [35] [34]. These platforms share a common foundation of integrating system-dependent (physiological) parameters with drug-dependent (physicochemical and ADME) parameters, but differ in their specific implementation approaches, mathematical algorithms, and specialized application modules [36].

A key advancement in PBPK platform development has been the incorporation of compartmental absorption models such as the Advanced Dissolution, Absorption and Metabolism (ADAM) model in Simcyp and the Advanced Compartmental Absorption and Transit (ACAT) model in GastroPlus [35] [34]. These models segment the GI tract into multiple compartments representing different anatomical regions (stomach, duodenum, jejunum, ileum, colon), each with distinct physiological characteristics including pH, surface area, fluid volume, and bile salt concentrations that collectively influence drug absorption [34]. This compartmental approach represents a significant evolution from earlier "mixing tank" models that treated the entire GI tract as a single, well-stirred compartment [34].

Performance Comparison and Validation

Recent studies have systematically evaluated the prediction performance of PBPK platforms for oral absorption, with particular focus on parameter optimization to improve accuracy. A 2025 retrospective analysis of bottom-up PBPK model development at AbbVie using Simcyp Simulator demonstrated how optimization of key system parameters significantly improved prediction accuracy for oral absorption [37].

Table 1: Impact of Parameter Optimization on PBPK Prediction Performance in Simcyp

| Parameter Combination | Cmax Predictions Within 3-fold | AUCINF Predictions Within 3-fold | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original GI physiology + default P-gp REF (1.5) + adjusted ISEF | 43% | 43% | Baseline performance |

| New GI physiology + default P-gp REF (1.5) + adjusted ISEF | 76% | Not specified | Improved absorption for low solubility compounds |

| New GI physiology + P-gp REF (0.5) + default ISEF | 86% | 81% | Optimal for P-gp substrates |

| Original GI physiology + default P-gp REF (1.5) + default ISEF | Not specified | 48% | Improved clearance prediction |

The implementation of "New GI physiology" in Simcyp Version 20, developed through extensive meta-analysis of human intestinal parameters, resulted in substantial improvement in Cmax predictions (76% within 3-fold vs. 43% with Original GI physiology) [37]. This enhancement is particularly valuable for low-solubility compounds whose absorption had been systematically underpredicted [37]. Further optimization of P-glycoprotein Relative Expression Factor (REF) to 0.5 additionally improved Cmax predictions for P-gp substrates to 86% within 3-fold, while using default recombinant CYP enzyme intersystem extrapolation factor (ISEF) values provided the most accurate area under the curve (AUCINF) predictions (81% within 3-fold) [37].

Regulatory applications of PBPK modeling further demonstrate the utility and validation of these platforms. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has utilized PBPK absorption modeling to support bioequivalence assessments, evaluate food effects, justify biowaivers, and assess the impact of sex differences on drug exposure [38]. In one case example, the FDA employed PBPK modeling to evaluate whether observed differences in in vitro alcohol-induced dose dumping between test and reference products would translate to clinically significant differences in systemic exposure, ultimately determining that the increased release did not pose a safety concern [38].

Critical Parameters for Simulating Oral Absorption

Fundamental Absorption Processes

PBPK models of oral absorption mechanistically represent four fundamental processes that collectively determine the rate and extent of drug absorption: solubility, dissolution, precipitation, and permeation [39]. Each process depends on the interplay between drug-specific properties and physiological conditions throughout the GI tract.

Solubility is not represented as a single value in PBPK models but rather as a dynamic parameter that varies along the GI tract due to regional differences in pH and bile salt concentrations [39]. For weak acids and bases, the pH-dependent ionization significantly influences solubility, with weak bases typically showing higher solubility in the acidic stomach and lower solubility in the near-neutral small intestine [39]. Measuring the pH-solubility profile and bile salt micelle partition coefficient (using media such as FaSSIF) provides critical inputs for PBPK software to calculate regional solubility variations [39].

Dissolution rate determines how quickly solid drug particles dissolve in GI fluids and is commonly described using adaptations of the Noyes-Whitney equation [34]. The dissolution rate depends on solid surface area, solubility, concentration gradient, and fluid hydrodynamics [39]. PBPK platforms incorporate semi-mechanistic dissolution models (z-factor, Wang-Flanagan, Johnson, P-PSD) that translate in vitro dissolution data to predictions of in vivo dissolution by accounting for differences in experimental conditions and physiological parameters [39].

Precipitation may occur when dissolved drug concentrations exceed thermodynamic solubility, particularly for weakly basic drugs that transition from acidic stomach to neutral intestine or for formulations designed to generate supersaturation (e.g., amorphous solid dispersions) [39]. The precipitation rate is drug-dependent and can be determined using transfer tests that simulate the transition from gastric to intestinal conditions [39]. In PBPK models, precipitation is typically simulated using a mean precipitation time (MPT) parameter derived from in vitro experiments [39].

Permeation describes the transport of dissolved drug across the intestinal membrane into systemic circulation and depends on effective permeability (Peff), available surface area, and drug concentration at the absorption site [39] [34]. Human Peff can be predicted using quantitative structure-activity relationship models, measured using cell monolayers (Caco-2, MDCK), or estimated from in situ animal models [39]. PBPK platforms incorporate correlations to translate these experimental measurements to human in vivo permeability values [39].

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

The relative importance of solubility, dissolution, precipitation, and permeation parameters varies depending on the specific drug, formulation, and physiological conditions [39]. Parameter sensitivity analysis (PSA) within PBPK software identifies which inputs most significantly impact simulation outputs, guiding resource allocation for experimental characterization [39]. For compounds with high permeability and low solubility (BCS Class II), dissolution and solubility parameters typically show high sensitivity, while for compounds with low permeability and high solubility (BCS Class III), permeation parameters dominate absorption variability [39].

Experimental Protocols for PBPK Model Development

Bottom-Up Model Development Workflow

The development of a bottom-up PBPK model for predicting oral absorption follows a systematic workflow that integrates in vitro assay data with physiological parameters. A standardized protocol ensures comprehensive characterization of critical drug properties and appropriate implementation in PBPK platforms.

Table 2: Key Experimental Assays for PBPK Absorption Model Inputs

| Parameter Category | Experimental Assays | Data Application in PBPK Models |

|---|---|---|

| Solubility | pH-solubility profile (pH 1-8); Solubility in FaSSIF/FeSSIF; Solid form characterization | Input for regional solubility calculations; Determination of bile partition coefficient |

| Dissolution | USP Apparatus 1/2; µDiss Profiler; Transfer model systems | Development of biopredictive dissolution method; Determination of dissolution rate constants |

| Permeability | Caco-2/MDCK assays; PAMPA; In situ perfusion | Estimation of human effective permeability (Peff); Identification of transporter involvement |

| Metabolism | Recombinant CYP enzymes; Human liver microsomes; Hepatocytes | Calculation of intrinsic clearance; ISEF optimization for IVIVE |

| Transport | Transporter overexpression systems; Relative expression factors | Quantification of transporter-mediated flux; REF optimization |

Step 1: Compound Characterization - Conduct comprehensive in vitro assays to determine fundamental physicochemical properties including pKa, log P, pH-solubility profile, bile salt partition coefficient, solid form stability, and permeability across biological membranes [39]. For compounds susceptible to metabolism, determine intrinsic clearance using recombinant CYP enzymes (with ISEF adjustment) or human hepatocytes [37].

Step 2: Dissolution Method Development - Establish biopredictive dissolution methods using appropriate apparatus (USP 1, 2, or µDiss Profiler) with media that simulate gastric and intestinal conditions [39]. For compounds with potential precipitation risks, implement transfer tests that simulate the transition from gastric to intestinal environment [39].

Step 3: Model Implementation - Input characterized parameters into PBPK platform, selecting appropriate absorption model (e.g., ADAM in Simcyp, ACAT in GastroPlus) and system parameters (e.g., GI physiology, transporter REF values) [37] [39]. For population simulations, incorporate appropriate variability in physiological parameters (organ volumes, blood flows, enzyme abundances) [36].

Step 4: Model Verification - Conduct parameter sensitivity analysis to identify critical inputs with greatest impact on absorption predictions [39]. Verify model performance against available in vivo data (e.g., preclinical pharmacokinetics) and refine parameters as needed [37] [36].

Step 5: Prediction and Validation - Apply verified model to predict human oral absorption and pharmacokinetics. For regulatory applications, establish model credibility through qualification for specific context of use following established frameworks [36].

Regulatory Qualification Framework

The qualification of PBPK models for regulatory submissions follows a structured framework that encompasses both platform qualification and model validation [36]. Platform qualification demonstrates the predictive capability of the PBPK software for a specific context of use, while model validation verifies that a compound-specific model is appropriately developed and suitable for addressing the regulatory question [36]. The qualification process includes assessment of software integrity, mathematical correctness, algorithm accuracy, and predictive performance for relevant compound classes [36]. For absorption models, qualification typically involves demonstrating accurate prediction of food effects, dose proportionality, formulation differences, and drug-drug interactions at the absorption site [38].

Visualization of PBPK Modeling Workflow

Oral Absorption PBPK Modeling Process

The following diagram illustrates the integrated workflow for developing and applying PBPK models to predict oral absorption, highlighting the sequential processes and key parameters.

PBPK Modeling Workflow for Oral Absorption Prediction

GI Tract Compartmental Structure

The compartmental representation of the gastrointestinal tract in modern PBPK absorption models captures regional variations in physiology that critically influence drug absorption.

GI Tract Compartmental Structure in PBPK Absorption Models

Research Tools and Reagents

Successful implementation of PBPK modeling for oral absorption prediction relies on specialized research tools, software platforms, and experimental systems. The following table catalogues essential solutions used in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for PBPK Absorption Modeling

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Application in PBPK Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| PBPK Software Platforms | Simcyp Simulator, GastroPlus, PK-Sim | Integrated PBPK/PD modeling, population simulations, regulatory submission support |

| In Vitro Dissolution Systems | USP Apparatus 1/2, µDiss Profiler, Transfer Model Systems | Generation of biopredictive dissolution data for model input |

| Permeability Assay Systems | Caco-2 cell models, MDCK cells, PAMPA, In situ perfusion | Determination of effective permeability (Peff) for absorption scaling |

| Solubility & Precipitation Assays | pH-solubility profiling, FaSSIF/FeSSIF, transfer tests | Characterization of regional solubility and precipitation risk |

| Metabolism & Transport Systems | Recombinant CYP enzymes, human hepatocytes, transporter assays | IVIVE of metabolic clearance and transporter interactions |

PBPK modeling represents a sophisticated, mechanistic approach to predicting oral drug absorption that integrates physiological understanding with drug-specific properties. The comparative analysis of PBPK platforms reveals continuous evolution in model sophistication, with recent advances in GI physiology parameters and system-specific scaling factors significantly improving prediction accuracy [37]. The optimal performance achieved with combined parameter optimization (86% of Cmax predictions within 3-fold for P-gp substrates) demonstrates the potential for highly reliable bottom-up predictions when appropriate system parameters are implemented [37].

The utility of PBPK absorption modeling extends throughout the drug development continuum, from early candidate selection to regulatory submission support. For comparative pharmacokinetics research examining oral versus intravenous administration, PBPK models provide a mechanistic framework to deconvolute the complex processes that differentiate these routes, particularly first-pass metabolism and absorption limitations that reduce oral bioavailability [34]. As these models continue to evolve with refined physiological parameters and improved IVIVE approaches, their role in guiding formulation strategy, clinical trial design, and regulatory decisions is expected to expand further [38] [36].

In the comparative pharmacokinetics of oral versus intravenous administration, a fundamental challenge has been obtaining intravenous pharmacokinetic (PK) data early in drug development. Traditional two-period crossover studies require extensive toxicology support and Good Manufacturing Practice (GMP)-quality IV formulations, making them resource-intensive. The microtracer approach revolutionizes this paradigm by enabling the simultaneous assessment of absolute bioavailability and IV PK using a minimally toxic, sub-therapeutic IV microtracer dose administered concomitantly with a therapeutic oral dose. This method provides critical IV pharmacokinetic parameters without standalone IV toxicology studies, accelerating early clinical development while maintaining scientific rigor and regulatory compliance.

Understanding a drug's absolute oral bioavailability (F) is crucial for development decisions, formulation optimization, and understanding exposure-response relationships. Absolute bioavailability is calculated by comparing systemic exposure after oral administration to exposure after IV administration: F = (AUCoral × DoseIV) / (AUCIV × Doseoral). Traditionally, this required separate clinical studies with full therapeutic IV doses, necessitating:

- Comprehensive IV toxicology studies in animals

- GMP-quality IV formulation development

- Two-period crossover designs with potential temporal effects

The microtracer approach circumvents these hurdles through the co-administration of a therapeutic oral dose with a minuscule IV dose containing a radiolabeled (¹â´C) or stable isotope (¹³C) version of the drug. This design captures both oral and IV PK from the same plasma samples at the same time, eliminating period effects while providing complete IV PK characterization with minimal radioactive exposure and regulatory burden.

Microtracer Methodology: Technical Implementation

Core Experimental Design

The microtracer approach employs an open-label, single-period design where subjects receive: