Pharmacogenomics in Personalized Medicine: Integrating Genomic Data to Revolutionize Drug Development and Clinical Practice

This article examines the transformative role of pharmacogenomics in advancing personalized medicine for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Pharmacogenomics in Personalized Medicine: Integrating Genomic Data to Revolutionize Drug Development and Clinical Practice

Abstract

This article examines the transformative role of pharmacogenomics in advancing personalized medicine for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals. It explores the foundational principles connecting genetic variation to individual drug responses, methodologies for clinical implementation across therapeutic areas, strategies to overcome economic and technological barriers, and validation through global regulatory frameworks and cost-effectiveness analyses. The synthesis provides a comprehensive roadmap for integrating pharmacogenomics into drug development pipelines and clinical care to enhance therapeutic efficacy and patient safety.

Genetic Foundations of Variable Drug Response: From Historical Observations to Genomic Mechanisms

Defining Pharmacogenomics within the Precision Medicine Paradigm

Pharmacogenomics (PGx) is a foundational component of precision medicine, dedicated to understanding how an individual's genetic makeup influences their response to medications [1]. The field moves clinical practice away from a "one-size-fits-all" model toward a personalized approach, optimizing drug selection and dosing to maximize efficacy and minimize adverse effects [2]. This paradigm shift is driven by the recognition that genetic polymorphisms in genes encoding drug-metabolizing enzymes, transporters, and targets are a major source of interindividual variability in drug response [3] [4]. The ultimate goal of pharmacogenomics is to replace the traditional trial-and-error method of prescribing with genetically informed, precision prescribing, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes and enhancing patient safety [2].

The clinical significance of pharmacogenomics is profound. For instance, an analysis of the 100,000 Genomes Project revealed that 62.7% of individuals carried an actionable pharmacogenetic variant, suggesting that 6% to 10% of people could benefit from genotype-guided dose adjustments or alternative drug regimens to achieve safer and more effective therapy [3]. Furthermore, real-world implementation studies have demonstrated that genotype-guided treatment can reduce the incidence of adverse drug events by up to 30% [5]. As genomic sequencing technologies continue to evolve, the integration of pharmacogenomic data into routine medical practice represents a significant advancement toward more personalized and effective treatment strategies across a wide range of therapeutic areas [3].

Core Principles and Genetic Architecture

Fundamental Terminology and Concepts

A standardized set of terms is essential for interpreting pharmacogenomic test results and clinical guidelines. Key concepts and nomenclature are defined below.

- Allele: One of two or more versions of a gene. An individual inherits two alleles for each gene, one from each parent [6].

- Diplotype: The combination of the two alleles (maternal and paternal) inherited by an individual for a particular gene. The diplotype is used to predict the drug-metabolizing phenotype [6] [5].

- Genotype: An individual's complete collection of genetic variants [6].

- Phenotype: The observable characteristic of an individual's ability to metabolize a drug, determined by their genotype (e.g., poor metabolizer, normal metabolizer) [6].

- Star (*) Allele Nomenclature: A standardized system for naming pharmacogenomic alleles. Alleles are designated by a gene symbol followed by an asterisk and a number (e.g.,

CYP2C19*2). This system accounts for all variants within a single haplotype, simplifying the reporting of complex genetic variation [6] [5].

From Genetic Variation to Clinical Presentation

The pathway from genetic variation to clinical outcome involves a structured translation process, illustrated below and detailed in the subsequent sections.

1. Genotype to Phenotype Translation The diplotype is translated into a predicted phenotype, which categorizes an individual's metabolic capacity [6] [5]. The major phenotypic categories are defined in Table 1.

Table 1: Standardized Pharmacogenomic Phenotype Definitions and Clinical Implications

| Metabolizer Status (Phenotype) | Functional Definition | Example Genotype (CYP2D6) | Example Clinical Recommendation (for Codeine) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ultrarapid Metabolizer | Increased enzyme activity | *1/*1x2 (duplication of normal function allele) |

Avoid use due to potential for serious toxicity (increased conversion to morphine) [6]. |

| Normal Metabolizer | Fully functional enzyme activity | *1/*1 (two normal function alleles) |

Use label-recommended dosing [6]. |

| Intermediate Metabolizer | Decreased enzyme activity | *1/*5 (one normal, one no function allele) |

Use label-recommended dosing [6]. |

| Poor Metabolizer | Little to no enzyme activity | *4/*5 (two no function alleles) |

Avoid use due to possibility of diminished analgesia (lack of conversion to morphine) [6]. |

2. Phenotype to Clinical Action The predicted phenotype is used to generate specific clinical recommendations for drug selection and dosing, as outlined in guidelines from consortia like the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG) [1] [5]. For example, the CPIC guideline for the opioid codeine, which is a prodrug activated by CYP2D6, recommends avoiding its use in both ultrarapid metabolizers (risk of toxicity) and poor metabolizers (lack of efficacy) [6] [3].

Key Molecular Players and Clinical Applications

Major Pharmacogenes and Drug Metabolism Pathways

The most critical genes in pharmacogenomics include those encoding cytochrome P450 (CYP) enzymes, which are involved in the phase I metabolism of an estimated 70-80% of all commonly prescribed drugs [3] [4]. Polymorphisms in these genes lead to distinct metabolic phenotypes with direct clinical consequences, as shown in Table 2.

Table 2: Major Pharmacogenes, Their Drug Substrates, and Clinical Consequences of Variation

| Gene | Example Drugs | Clinical Impact of Genetic Variation |

|---|---|---|

| CYP2C19 | Clopidogrel, proton pump inhibitors (e.g., omeprazole), antidepressants [3] | Poor metabolizers show reduced efficacy of clopidogrel, increasing risk of stent thrombosis and major adverse cardiac events [7] [2]. |

| CYP2D6 | Codeine, tramadol, tamoxifen, antidepressants, antipsychotics [3] | Ultrarapid metabolizers of codeine produce toxic morphine levels, risking fatal respiratory depression, especially in children [6] [3]. |

| CYP2C9 | Warfarin, siponimod, NSAIDs [3] [8] | Variants increase bleeding risk with warfarin; require genotype-guided dosing [9] [8]. |

| TPMT, NUDT15 | Thiopurines (mercaptopurine, thioguanine) [3] [8] | Poor metabolizers at high risk for severe, life-threatening myelosuppression; require drastic dose reduction or alternative agents [8]. |

| DPYD | Fluoropyrimidines (5-fluorouracil, capecitabine) [3] | Deficiency in the encoded enzyme predicts severe and potentially fatal toxicity; requires dose adjustment or alternative therapy [3] [10]. |

| HLA-B | Carbamazepine, allopurinol, abacavir [1] [8] | Specific alleles (e.g., HLA-B*15:02 for carbamazepine) confer high risk for life-threatening cutaneous adverse reactions like Stevens-Johnson Syndrome [1]. |

Analytical Methods and Experimental Protocols

Standard Genotyping and Star Allele Calling

The standard methodology for determining an individual's pharmacogenotype involves targeted genotyping or next-generation sequencing (NGS), followed by computational star allele calling.

Detailed Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation & Sequencing: Extract genomic DNA from a patient specimen (e.g., blood, saliva). For NGS, prepare a sequencing library, which may involve enrichment for a panel of pharmacogenes. Sequence the DNA using a high-throughput platform [5].

- Data Pre-processing: Align the resulting sequencing reads (in FASTQ format) to a reference genome (e.g., GRCh38) using alignment algorithms like BWA-MEM. Process the aligned data (BAM files) by sorting, indexing, and marking duplicates using tools like Samtools and Picard [5].

- Star Allele Calling: Analyze the pre-processed BAM files using specialized computational tools to determine the star allele diplotype. Commonly used tools include:

- Aldy: A versatile tool that can handle complex structural variations and copy number variants [5].

- PyPGx: A Python-based toolkit that supports a wide range of pharmacogenes and provides phenotype prediction [5].

- StellarPGx: Another robust caller designed for accurate diplotype assignment [5]. It is considered best practice to use at least two callers for cross-validation due to the complexity of some pharmacogenes [5].

- Phenotype and Recommendation Assignment: Translate the consensus diplotype into a phenotype using standardized tables (see Table 1). Apply evidence-based clinical guidelines (e.g., from CPIC) to generate a therapeutic recommendation [5].

Addressing the Dynamic Nature of Nomenclature

A critical consideration in PGx research and testing is the dynamic nature of the star allele nomenclature. The Pharmacogene Variation Consortium (PharmVar) serves as the central repository for allele definitions, which are continuously updated as new alleles are discovered and characterized [6] [5]. Between early version 1.1.9 and version 6.2, the PharmVar database added 471 core alleles and redefined or removed 49 others [5]. This evolution means that an individual's diplotype call can change over time if different database versions are used, which can, in rare cases, alter clinical recommendations. Researchers must document the PharmVar version used and implement cross-tool validation to ensure the reliability of their results [5].

A successful PGx research program relies on a suite of key databases, software tools, and biological reagents, detailed in Table 3.

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Resources for Pharmacogenomics Research

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function and Utility |

|---|---|---|

| PharmVar (Pharmacogene Variation Consortium) | Database | The authoritative repository for the definitive star (*) allele nomenclature sequences and functional annotations for major pharmacogenes [6] [5]. |

| PharmGKB (Pharmacogenomics Knowledgebase) | Database | Curates knowledge about the impact of genetic variation on drug response, including clinical guidelines (CPIC, DPWG), drug labels, and variant annotations [1] [9]. |

| CPIC (Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium) | Guideline Body | Provides freely available, evidence-based, peer-reviewed guidelines for translating genetic test results into actionable prescribing decisions [1] [9] [8]. |

| GeT-RM (Genetic Testing Reference Materials) | Biological Reagents | Provides robust, characterized reference materials and cell lines for benchmarking and validating pharmacogenomic genotyping assays [5]. |

| Aldy, PyPGx, StellarPGx | Software Tool | Computational tools for determining star allele diplotypes from next-generation sequencing data (BAM/FASTQ files) [5]. |

| UK Biobank, All of Us | Biobank / Data Resource | Large-scale, EHR-linked biobanks with genomic data that enable discovery of novel drug-gene associations and investigation of PGx in real-world populations [9] [10]. |

Current Challenges and Future Directions

Despite its potential, the widespread clinical implementation of pharmacogenomics faces several significant barriers. Key challenges, as identified in recent literature, are summarized in Table 4 alongside proposed solutions.

Table 4: Barriers to Clinical Implementation of Pharmacogenomics and Potential Solutions

| Domain | Cited Barrier | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Equity and Inclusion | Underrepresentation of diverse populations in PGx research and implementation; can introduce healthcare disparities and weaken evidence [9]. | Increase genetic diversity in research cohorts (e.g., All of Us); implement pan-ethnic testing panels that include alleles common in all populations [9]. |

| Evidence and Guidelines | Insufficient evidence for some drug-gene pairs; genetic exceptionalism demanding RCTs for every use case [9] [7]. | Incorporate different forms of evidence (e.g., mechanistic, pharmacokinetic); disseminate guidelines to frontline clinicians [9]. |

| Clinical Integration | Lack of EHR integration and clinical decision support (CDS); clinician resistance and knowledge gaps [9] [4]. | Develop and adopt data standards for genomic information in EHRs; expand competency-based education for healthcare professionals [9] [2]. |

| Payer Coverage & Reimbursement | Sparse, inconsistent, or absent insurance coverage for multigene panels and preemptive testing [9] [7] [4]. | Establish uniform evidence thresholds for coverage; demonstrate cost-effectiveness through robust health economics studies [9] [7]. |

Emerging technologies are poised to address some of these challenges. Long-read sequencing provides contiguous reads that span tens of kilobases, enabling comprehensive mapping of highly polymorphic and complex genes like CYP2D6, which is prone to gene duplications and hybrid alleles that are difficult to detect with short-read technologies [10]. Artificial intelligence and machine learning are being deployed to analyze complex, multi-dimensional datasets, predict the functional impact of genetic variants from sequence data alone, and even forecast individual drug response based on integrated multi-omics profiles [10]. The integration of polygenic risk scores (PGS), which aggregate the effects of many variants across the genome, represents a move beyond single gene-drug interactions to predict more complex treatment outcomes for conditions like type 2 diabetes and schizophrenia [10].

Pharmacogenomics stands as a critical and rapidly advancing pillar of precision medicine. By deciphering the genetic determinants of drug response, it provides a powerful framework for replacing empirical prescribing with a more predictive, personalized approach. The field has established a robust foundation of key genes and alleles, standardized nomenclature, and evidence-based guidelines for an growing number of drug-gene pairs. While challenges related to diversity, clinical implementation, and reimbursement remain active areas of work, technological innovations in sequencing, data integration, and analytics are accelerating the field's progress. The continued collaboration between researchers, clinicians, and policymakers is essential to overcome these hurdles, ensuring that the promise of pharmacogenomics—to deliver the right drug at the right dose to every patient—becomes a ubiquitous and equitable reality in healthcare.

Pharmacogenomics is the study of how an individual's entire genome influences their response to drugs, playing a pivotal role in the development of personalized medicine [11]. The foundation of drug response rests on two core principles: pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics.

- Pharmacokinetics describes what the body does to a drug, encompassing the processes of Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) [12].

- Pharmacodynamics describes what the drug does to the body, involving the drug's biological effects on its target, such as a receptor or enzyme [12].

Genetic variations can alter both of these processes, accounting for 20% to 95% of inter-individual variability in drug metabolism and response [11]. Understanding these genetic influences is essential for tailoring therapies to maximize efficacy and minimize adverse effects, thereby fulfilling the promise of personalized medicine.

Genetic Influences on Pharmacokinetics (ADME)

Pharmacokinetic interactions determine how a drug is processed by the body. Genetic polymorphisms, particularly in genes encoding drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters, can significantly alter this processing, leading to variable drug concentrations and, consequently, variable therapeutic outcomes [12].

Key Enzymes and Genetic Variants in Drug Metabolism

The cytochrome P450 (CYP450) enzyme family is responsible for metabolizing the majority of drugs [11]. Polymorphisms in the genes coding for these enzymes can profoundly influence drug response, causing it to be normal, increased, reduced, or completely neutralized [11]. These genetic variations give rise to distinct metabolic phenotypes.

Table: Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Metabolism

| Gene | Metabolism Phenotype | Clinical Implication | Example Drugs |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2D6 | Ultra-rapid Metabolizer (UM) | Reduced drug efficacy; for prodrugs, risk of toxicity | Codeine, Tamoxifen, Tricyclic antidepressants [12] [11] |

| Poor Metabolizer (PM) | Increased risk of side effects | ||

| CYP2C19 | Poor Metabolizer (PM) | Reduced activation of prodrug, risk of therapeutic failure | Clopidogrel, Proton pump inhibitors [11] [13] |

| CYP2C9 | Poor Metabolizer (PM) | Reduced metabolism, risk of toxicity and dosing variability | Warfarin, Phenytoin [11] |

| DPYD | Poor Metabolizer (PM) | Severe toxicity due to drug accumulation | Capecitabine, Fluorouracil [13] |

The clinical impact of being a slow metabolizer depends on the drug's properties. For active drugs, slow metabolism leads to accumulation and increased risk of toxicity. For prodrugs (inactive compounds that require metabolic activation), slow metabolism can result in therapeutic failure due to insufficient formation of the active compound [13]. A prime example is clopidogrel, where patients with CYP2C19 poor metabolizer status produce low levels of the active metabolite, leading to a higher risk of cardiovascular events [11] [13].

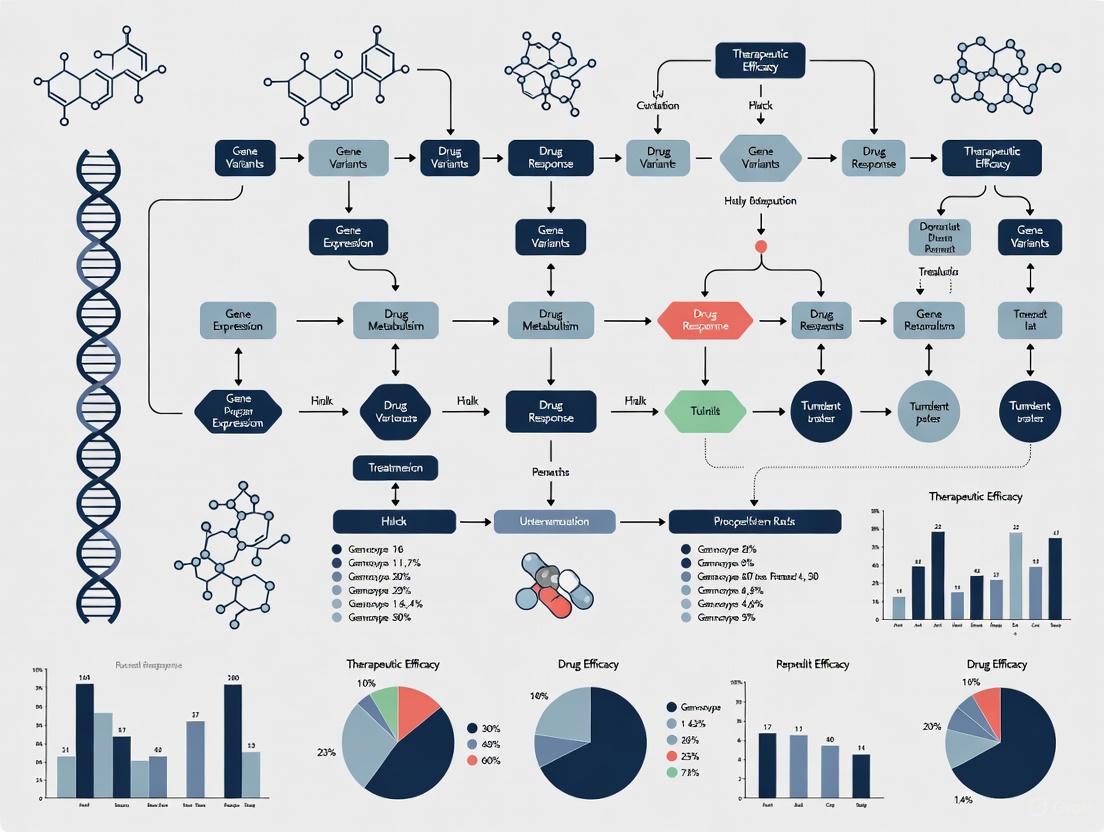

Diagram 1: The pathway from genetic variant to altered drug response via pharmacokinetics.

Genetic Influences on Pharmacodynamics

While pharmacokinetics deals with drug exposure, pharmacodynamics concerns the drug's effect on the body, including its therapeutic action and the risk of adverse reactions [12]. Genetic variants can alter the structure or function of a drug's target (e.g., a receptor or enzyme), changing the body's sensitivity to the drug irrespective of its concentration.

A key example involves the drug warfarin. Variants in the VKORC1 gene, which encodes the drug's target enzyme (vitamin K epoxide reductase), affect the drug's pharmacodynamics. These variants influence the enzyme's sensitivity to warfarin, directly impacting the required dosage [12] [11]. Another critical pharmacodynamic mechanism involves the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genes. Specific variants, such as HLA-B1502, are strongly associated with an increased risk of severe hypersensitivity reactions like Stevens-Johnson syndrome in patients taking carbamazepine [11].

Table: Pharmacogenomic Biomarkers in Drug Targets and Safety

| Gene | Drug | Effect of Variant | Mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|

| VKORC1 | Warfarin | Altered dosing requirement | Pharmacodynamic: Alters sensitivity of drug target [12] [11] |

| HLA-B | Carbamazepine | Increased risk of severe skin reactions (SJS/TEN) | Pharmacodynamic: Alters immune-mediated drug reaction [11] |

| ERBB2 (HER2) | Trastuzumab | Determines drug eligibility and efficacy | Pharmacodynamic: Target overexpression drives drug efficacy [14] |

Integrating PK and PD: The Combined Genetic Influence

For many drugs, the overall response is a complex interplay of multiple genetic factors affecting both pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Warfarin provides a classic example of this dual influence, where dosing is affected by:

- Pharmacokinetic Gene: CYP2C9 variants affect the rate of warfarin metabolism [12] [11].

- Pharmacodynamic Gene: VKORC1 variants affect the sensitivity of the drug target [12] [11].

This multi-gene influence underscores the necessity of a comprehensive pharmacogenomic approach to accurately predict drug behavior, moving beyond single-gene tests to multi-gene panels for complex medications.

Diagram 2: The combined pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic genetic influences on warfarin dosing.

Experimental and Methodological Approaches

Research and clinical implementation in pharmacogenomics rely on robust methodologies to connect genetic variation to drug response phenotypes.

Genotyping and Sequencing Methodologies

The foundation of pharmacogenomic testing is identifying relevant genetic variants. These include:

- Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms (SNPs): Single base-pair substitutions that account for 90% of all human genetic variation [11]. The location of an SNP determines its functional impact.

- Structural Variations (SVs): Less frequent than SNPs but with greater functional consequences, SVs include insertions/deletions ("indels") and copy number variations (CNVs), which can lead to nonfunctional proteins [11].

Modern approaches often utilize multigene pharmacogenetic tests that simultaneously interrogate a panel of key genes (e.g., CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, VKORC1, DPYD) to provide a comprehensive profile. Adhering to recommendations from bodies like the Association for Molecular Pathology (AMP) ensures tests cover clinically relevant variants [9].

Phenotyping and Clinical Correlation

Linking genotype to a predicted phenotype is a critical step. For metabolic enzymes, this involves classifying individuals into one of four primary phenotypes:

- Poor Metabolizer (PM): Greatly reduced or absent enzyme activity.

- Intermediate Metabolizer (IM): Reduced enzyme activity.

- Normal/Extensive Metabolizer (EM): Standard enzyme activity.

- Ultra-rapid Metabolizer (UM): Increased enzyme activity [11].

The clinical interpretation of these phenotypes is standardized and disseminated through guidelines from consortia like the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG). These guidelines translate genetic test results into actionable clinical recommendations, such as "use an alternative drug" or "increase dose by 50%" [9].

Table: Essential Research Reagents and Resources

| Reagent / Resource | Function in PGx Research | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequencing Kits | Extract DNA and identify genetic variants from patient samples (blood/saliva) [13] | Whole genome sequencing, Targeted SNP panels |

| CPIC Guidelines | Translate genotype into actionable phenotype and prescribing guidance [9] | CPIC Guideline for Codeine (CYP2D6) |

| FDA Table of Biomarkers | Identify clinically recognized drug-gene pairs with regulatory backing [14] | FDA Biomarker Table (e.g., HLA-B*1502 & Carbamazepine) |

| PharmGKB | Curated knowledgebase of drug-gene relationships, evidence levels, and clinical guidelines [9] | PharmGKB.org |

| Phenotyping Assays | Functional validation of metabolic activity (e.g., via probe drugs) | CYP activity measured in hepatocytes or via metabolite ratio |

Implementation in Personalized Medicine and Current Challenges

The integration of pharmacogenomics into routine clinical practice is a central goal of personalized medicine. Its implementation allows clinicians to:

- Select the most effective drug for an individual.

- Optimize drug dosage from the outset.

- Avoid drugs with a high risk of severe adverse reactions for particular patients [13].

Significant progress has been made, with the FDA including pharmacogenomic biomarkers in the labeling for over 100 drugs, providing official recognition of their clinical importance [14]. However, several barriers to widespread adoption remain, including:

- Evidence and Guidelines: Insufficient evidence for some drug-gene pairs and the need for incorporation into broader medical society guidelines [9].

- Education: A lack of knowledge and confidence in using pharmacogenetic information among healthcare providers [9].

- Equity and Inclusion: The underrepresentation of diverse populations in pharmacogenetics research, which can lead to disparities in clinical utility and healthcare outcomes [9].

The genetic influences on the core principles of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics are a fundamental determinant of inter-individual drug response. The integration of this knowledge into drug development and clinical practice, through genotyping, phenotyping, and the application of clinical guidelines, is transforming the paradigm from a "one-size-fits-all" approach to a more effective and safer model of personalized medicine. Overcoming the remaining implementation challenges, particularly those related to evidence generation and health equity, is critical to fully realizing the potential of pharmacogenomics to improve patient outcomes.

In the field of personalized medicine, pharmacogenomics stands as a cornerstone, providing the scientific foundation for understanding how individual genetic makeup influences drug response. This technical guide examines the key genetic polymorphisms within the cytochrome P450 (CYP) superfamily and membrane transporter genes, which collectively govern the pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of a substantial proportion of clinically used drugs. Research demonstrates that genetic variants in these proteins explain 20-30% of interindividual differences in drug response, contributing significantly to both adverse drug reactions and therapeutic failures [15]. The clinical implementation of this knowledge is evidenced by the inclusion of pharmacogenomic information in over 390 drug labels by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [14]. This whitepaper provides researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical resource on these critical pharmacogenomic elements, framing them within the broader context of advancing personalized treatment strategies.

The Cytochrome P450 (CYP) Superfamily

Clinical Significance and Genetic Architecture

The CYP superfamily comprises 57 functional enzymes in humans that metabolize more than 80% of all clinically used medications [15]. These hemoprotein enzymes catalyze the oxidation of numerous drugs, facilitating their elimination from the body. Among these, CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 are of paramount clinical importance due to their extensive polymorphism, broad substrate specificity, and significant impact on drug disposition and response.

CYP2D6 metabolizes approximately 25% of commonly prescribed drugs, including numerous antidepressants (paroxetine, fluvoxamine, amitriptyline), antipsychotics (haloperidol, risperidone), beta-blockers, antiemetics, and opioids [16] [15]. The CYP2C19 enzyme metabolizes drugs including the antiplatelet agent clopidogrel, tricyclic antidepressants (amitriptyline, clomipramine), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (citalopram, sertraline), and the antifungal voriconazole [16] [15].

These genes are highly polymorphic, with the Pharmacogene Variation Consortium categorizing 129 known allelic variants for CYP2D6 and 35 clinically relevant variants for CYP2C19 [16]. These polymorphisms result in distinct metabolic phenotypes, classified for CYP2C19 as ultrarapid metabolizers (UM), rapid metabolizers (RM), normal metabolizers (NM), intermediate metabolizers (IM), and poor metabolizers (PM); and for CYP2D6 as UM, NM, IM, and PM [16].

Key Polymorphisms and Functional Consequences

The most clinically significant polymorphisms and their functional impacts are summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Key CYP Gene Polymorphisms and Functional Consequences

| Gene | Key Variant(s) | Functional Effect | Molecular Consequence | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C19 | *2 (rs4244285) | Loss-of-function | Aberrant splicing, premature stop codon [15] | Reduced activation of clopidogrel; altered antidepressant exposure |

| *17 (rs12248560) | Increased function | Regulatory polymorphism increasing transcriptional activity [15] | Potential therapeutic failure due to rapid metabolism; requires dose adjustment | |

| CYP2D6 | *3 (rs35742686), *4 (rs3892097), *5 (gene deletion), *6 (rs5030655) | Loss-of-function | Frameshift, splicing defect, gene deletion, base change [16] | Increased drug exposure and toxicity risk for substrates including tricyclic antidepressants and codeine |

| *41 (rs28371725) | Reduced function | Splicing defect [16] | Intermediate metabolizer phenotype | |

| *1xN, *2xN (gene duplication) | Increased function | Multiple functional gene copies [15] | Ultrarapid metabolism; potential therapeutic failure |

The following diagram illustrates the metabolic pathway implications of these polymorphisms:

Figure 1: Impact of Genetic Polymorphisms on Drug Metabolism Pathways. Genetic variants in CYP genes determine metabolic capacity, influencing metabolite exposure levels and clinical outcomes.

Population Distribution and Geographical Gradients

The prevalence of important CYP alleles demonstrates significant geographical gradients across Europe, reflective of the continent's migratory history [15].

Table 2: Population Frequencies of Key CYP Alleles Across European Populations

| Population Region | CYP2C19*2 (%) | CYP2C19*17 (%) | CYP2D6*4 (%) | CYP2D6*5 (%) | CYP2D6 Duplications (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Northern Europe (Sweden, Denmark, Norway) | 13-15% | 19-22% | 19-25% | 4-6% | 0.5-1% |

| Central Europe (Czech Republic, Poland, Slovakia) | 8-12% | 29-33% | 20-25% | ~3% | 1-2% |

| Southern Europe (Italy, Spain, Greece) | 12-17% | 11-18% | 16-18% | 1-2% | 3-6% |

| Finland (distinct pattern) | 17.5% | ~20% | 10% | 2.2% | 4.3% |

These geographical gradients have profound implications for multinational drug development and clinical trial design, as the proportion of patients with atypical metabolic phenotypes varies significantly between regions [15].

Membrane Drug Transporters

Membrane transporters are integral membrane proteins that actively or passively control the influx and efflux of drugs and other molecules across biological membranes [17]. They play crucial roles in drug absorption, distribution, and elimination, significantly impacting both drug pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics. Two major superfamilies dominate this field: the ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which are primarily efflux transporters that utilize ATP hydrolysis to pump substrates out of cells, and the Solute Carrier (SLC) transporters, which include both influx and efflux transporters [18] [17].

The International Transporter Consortium (ITC) and regulatory authorities have identified specific transporters as clinically important determinants of drug disposition and drug-drug interactions [19]. According to the ITC, polymorphisms in ABCG2 (BCRP), SLCO1B1 (OATP1B1), and the emerging transporter SLC22A1 (OCT1) should be considered during drug development due to substantial evidence linking them to interindividual differences in drug levels, toxicities, and responses [19].

Key Transporter Polymorphisms

Table 3: Clinically Important Drug Transporter Polymorphisms

| Transporter | Gene | Key Polymorphism | Functional Effect | Clinical Impact |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| BCRP | ABCG2 | rs2231142 (Q141K) | Reduced protein expression and transport activity [19] | Altered pharmacokinetics of sulfasalazine, rosuvastatin; increased uric acid levels and gout risk [19] [20] |

| OATP1B1 | SLCO1B1 | rs4149056 (Val174Ala) | Reduced transport activity to hepatocytes [19] [18] | Increased systemic exposure to statins; higher risk of statin-induced myopathy [19] [18] |

| OCT1 | SLC22A1 | Multiple reduced function variants (e.g., R61C, M420del, G465R) | Decreased uptake activity into hepatocytes [19] | Altered metformin disposition and response; potential impact on several prescription drugs [19] |

| P-glycoprotein | ABCB1 | C3435T (synonymous) | Altered protein conformation and substrate specificity [21] | Controversial impact on digoxin, HIV protease inhibitors, and chemotherapy drug pharmacokinetics [21] |

The protein structures and cellular localization of these critical transporters are visualized below:

Figure 2: Key Drug Transporters in Hepatocyte Drug Handling. Uptake and efflux transporters work in concert to determine drug disposition, with polymorphisms impacting function at multiple sites.

Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) Validation

The clinical importance of transporter polymorphisms is underscored by GWAS findings. To date, a total of eight GWAS have reported genome-wide significant associations (p<5×10â»â¸) between polymorphisms in ABCG2 and SLCO1B1 and drug disposition or response [19]. These associations have been described for drugs used in the treatment of lipid disorders (statins), gout (allopurinol), cancer (methotrexate), and cardiovascular disorders (ticagrelor) [19]. Among these eight GWAS, four are related to drug disposition and four are related to therapeutic or adverse drug response.

For SLCO1B1, the nonsynonymous polymorphism rs4149056 (Val174Ala) has been either directly associated with pharmacologic traits or is in linkage disequilibrium with another variant that has been associated with the trait [19]. For ABCG2, multiple polymorphisms have been associated with various traits, though typically the missense polymorphism rs2231142 (Q141K) is in linkage disequilibrium with the associated polymorphisms [19].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Genotyping Techniques and Functional Characterization

Robust experimental protocols are essential for reliable pharmacogenomic research. The following methodologies represent current best practices for investigating CYP and transporter polymorphisms.

Genotyping Methods:

- qPCR with TaqMan Probes: Standard and custom TaqMan reagents provide specific allele discrimination for known variants. This method was successfully employed in a study of 742 Bulgarian psychiatric patients for CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 genotyping [16].

- Copy Number Variation (CNV) Analysis: Specific PCR primers are used to detect gene deletions (e.g., CYP2D65) and duplications (e.g., CYP2D61xN, *2xN) [16].

- Massively Parallel Sequencing: Next-generation sequencing approaches allow for comprehensive variant discovery across pharmacogenes, identifying both common and rare variants [19].

Functional Characterization Workflow: The following diagram outlines a standardized approach for functional characterization of polymorphisms:

Figure 3: Experimental Workflow for Characterizing Pharmacogenetic Variants. A multidisciplinary approach integrates in vitro and clinical studies to establish functional impact.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Pharmacogenomic Studies

| Reagent/Cell Line | Application | Function/Significance |

|---|---|---|

| MDR1-MDCK | Transcellular transport assays | Madin-Darby canine kidney cells overexpressing human P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) to study efflux transport |

| HEK293 Transfectants | Functional characterization of variants | Human embryonic kidney cells transfected with wild-type or polymorphic transporter genes for uptake assays |

| Ko143 | Specific BCRP inhibition | Potent and selective ABCG2 inhibitor used to confirm BCRP-specific transport in vitro [20] |

| TaqMan Genotyping Assays | Allelic discrimination | Fluorogenic 5'-nuclease chemistry for specific SNP detection and quantitation |

| Human Hepatocytes | Integrated transport and metabolism studies | Primary cells maintaining native expression of drug transporters and metabolizing enzymes |

| Vesicular Transport Assays | ABC transporter characterization | Membrane vesicles prepared from transporter-overexpressing cells to study ATP-dependent transport |

| AJM 290 | AJM 290, MF:C20H14FNO4S, MW:383.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| BRITE-338733 | 2-(4-(5-Ethylfuran-2-yl)-6-(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-4-ylamino)pyridin-2-yl)-4-methylphenol | High-purity 2-(4-(5-Ethylfuran-2-yl)-6-(2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidin-4-ylamino)pyridin-2-yl)-4-methylphenol for research applications. This product is For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

The comprehensive characterization of genetic polymorphisms in CYP enzymes and drug transporters represents a fundamental component of personalized medicine research. The clinical pharmacogenetics of CYP2D6, CYP2C19, ABCG2, SLCO1B1, and SLC22A1 have matured sufficiently to warrant consideration in drug development programs and, in many cases, clinical practice. The geographical gradients in allele frequencies emphasize the importance of population-specific considerations in both research and clinical implementation. As pharmacogenomic strategies continue to evolve, supported by initiatives such as the European Partnership for Personalised Medicine's JTC2025 call on "Pharmacogenomic Strategies for Personalised Medicine" [22], the integration of this knowledge into drug development and clinical practice will be essential for advancing the precision medicine paradigm, ultimately enabling tailored therapeutic strategies that optimize efficacy while minimizing adverse drug reactions.

The journey to understand the blueprint of life represents one of science's most profound evolutions, transitioning from philosophical speculation to precise molecular intervention. This historical progression, originating with ancient Greek philosophers like Pythagoras and culminating in today's genomic era, established the fundamental principles that enable modern pharmacogenomics. Personalized medicine, which aims to tailor medical treatment to an individual's genetic makeup, is the direct descendant of centuries of research into the laws of heredity and biological information [23]. The field of pharmacogenomics (PGx) now applies this knowledge to study how interindividual variations in DNA sequence relate to drug response, thereby improving therapeutic outcomes by optimizing drug selection and dosing, reducing adverse drug reactions, and increasing overall treatment efficacy [24]. This whitepaper traces these critical historical milestones, detailing their technical foundations and their collective role in forging the tools for contemporary personalized drug therapy.

Historical Foundations: From Speculation to Mendel's Laws

The human understanding of heredity began not with experimentation, but with observation and philosophical reasoning.

Ancient and Classical Theories

In approximately 500 BC, Greek philosophers such as Hippocrates and Pythagoras proposed early theories of heredity. Pythagoras believed that semen collected a physical essence, or "pangens," from all parts of the father's body, which then condensed into a new individual in the womb. This theory suggested that characteristics acquired by a parent during their lifetime could be passed to offspring [25]. Later, in around 300 BC, Aristotle challenged this view, noting that children could inherit traits from their mothers and grandparents. He introduced the concept of information being transmitted via a non-physical "form-giving principle" rather than a physical template, although he still believed this information was carried in semen and menstrual blood [26] [25].

The Birth of Experimental Genetics

The pivotal breakthrough came from the meticulous work of Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian friar. Between 1856 and 1865, he conducted systematic breeding experiments using pea plants (Pisum sativum). His quantitative approach allowed him to deduce the fundamental principles of inheritance [26].

- Experimental Methodology: Mendel hand-pollinated thousands of pea plants, carefully tracking seven distinct characteristics across generations. For each trait, he crossed pure-bred parent plants and statistically analyzed the patterns appearing in their hybrid offspring [25].

- Key Findings: His experiments revealed that traits are passed on in discrete units (later termed "genes") that do not blend but remain distinct across generations. He formulated the laws of segregation (each individual has two alleles for a trait, which separate during gamete formation) and independent assortment (genes for different traits are inherited independently of one another) [26]. Mendel himself referred to the "material creating" the character as "factors" [26].

Table 1: Key Historical Milestones in Genetics (c. 500 BC - 2003)

| Date | Figure(s) | Key Contribution | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| ~500 BC | Pythagoras & Hippocrates | Theory of "pangens" - hereditary material collected from all body parts [25]. | Philosophical reasoning and observation. |

| ~300 BC | Aristotle | Proposed information ("form-giving principle") as the basis of heredity [26] [25]. | Observation of family traits and embryo development (e.g., chicken eggs) [25]. |

| 1865 | Gregor Mendel | Established laws of inheritance (segregation and independent assortment) [26]. | Statistical analysis of trait inheritance in thousands of hand-pollinated pea plants [26] [25]. |

| 1900 | Hugo de Vries, Carl Correns, Erich von Tschermak | Independently rediscovered and confirmed Mendel's work [26]. | Repetition of plant hybridisation experiments. |

| 1910 | Thomas Hunt Morgan | Established that genes reside on chromosomes, using fruit flies (D. melanogaster) [26]. | Cross-breeding experiments tracking eye color mutations in fruit flies [25]. |

| 1944 | Oswald Avery, Colin MacLeod, Maclyn McCarty | Identified DNA as the molecule carrying genetic information [27]. | In vitro transformation of bacteria. |

| 1953 | James Watson, Francis Crick, Rosalind Franklin, Maurice Wilkins | Determined the double-helical structure of DNA [27]. | X-ray crystallography (Franklin) and model building. |

| 2003 | International Human Genome Project | Completed the sequencing of the human genome, confirming ~20,000-25,000 genes [27] [28]. | Large-scale capillary sequencing (Sanger method) of DNA fragments. |

The Rise of Modern Genomics and Pharmacogenomics

The 20th century witnessed the transition from classical genetics to molecular biology and genomics, setting the stage for pharmacogenomics.

From DNA to the Genome

The period between the 1950s and the early 2000s was marked by a series of transformative discoveries. In 1953, the double-helix structure of DNA, proposed by James Watson and Francis Crick with critical contributions from Rosalind Franklin, revealed the molecular basis for genetic storage and replication [27]. The following decades saw the development of foundational tools like the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) in 1983, which allowed for the amplification of specific DNA sequences, and DNA profiling in 1984 [27]. The apex of this era was the Human Genome Project (HGP), launched in 1990 and declared complete in 2003. The HGP provided the first reference sequence of the entire human genome, confirming an estimated 20,000 to 25,000 genes and revolutionizing all aspects of biomedical research [27] [28].

The Emergence of Pharmacogenomics

With the human genome sequenced, researchers could systematically investigate the genetic basis for variable drug responses. Pharmacogenomics emerged as a discipline focused on how interindividual variations in DNA sequence impact drug efficacy and toxicity [24]. Key initiatives, such as the Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium (CPIC) and the Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group (DPWG), were formed to curate evidence and create clinical guidelines for gene-based drug prescribing [24] [29]. For example, the FDA-approved label for the antiplatelet drug clopidogrel now includes a warning that patients who are CYP2C19 poor metabolizers may experience diminished drug effectiveness, advising clinicians to consider alternative treatments [29].

Table 2: Modern Genomic and Pharmacogenomic Milestones (1978 - Present)

| Date | Initiative/Discovery | Significance | Impact on Personalized Medicine |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1978 | WHO Uppsala Monitoring Centre Established | Launched international pharmacovigilance collaboration, creating the Vigibase for adverse drug reaction (ADR) reports [29]. | Laid groundwork for post-marketing drug safety surveillance, a precursor to genetic ADR investigation. |

| 1990 | Human Genome Project Launched | International effort to sequence the entire human genome [27] [28]. | Provided the fundamental reference map for identifying genetic variants linked to disease and drug response. |

| 2003 | Human Genome Sequence Completed | Completed >92% of the human genome sequence, confirming ~20,000-25,000 genes [27]. | Enabled genome-wide association studies (GWAS) to find variants associated with drug metabolism and efficacy. |

| 2005-2010 | Early PGx Implementations | FDA adds PGx data to drug labels (e.g., warfarin); CPIC forms to create clinical guidelines [24] [29]. | Began translating genetic research into actionable clinical prescribing recommendations. |

| 2012 | CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Discovered | A versatile and precise method for editing genes [27]. | Opened possibilities for correcting genetic mutations that cause disease or alter drug response. |

| 2020 | FDA Table of Pharmacogenetic Associations | Listed 22 distinct drug-gene pairs with potential impact on safety or response [29]. | Consolidated and highlighted key PGx relationships for clinicians and regulators. |

| 2023 (Example) | Iran PGx Initiative | Population-specific study of 37 pharmacogenes to guide treatment in oncology, cardiology, and psychiatry [23]. | Demonstrates global adoption of PGx, highlighting need for population-specific data to guide prescribing. |

| 2025 (Future) | AI/ML in Pharmacovigilance | Advanced AI models to analyze complex genetic data for ADR risk prediction [29]. | Promises more proactive and individualized drug safety monitoring through pattern recognition in large datasets. |

Technical Frameworks for Clinical PGx Implementation

Translating PGx research into routine clinical practice requires a structured, multi-stakeholder approach.

Stakeholders and Implementation Pathways

The successful integration of PGx into a hospital setting involves a coordinated effort among at least eight key stakeholder groups [24]. Regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA authorize tests and provide drug labeling guidance. Hospital leadership secures funds and infrastructure, while the Pharmacy & Therapeutics Committee evaluates evidence and identifies the most actionable drug-gene pairs. The laboratory performs genotyping, Information Technology integrates results into electronic health records and clinical decision support systems, and healthcare providers ultimately order tests, interpret results, and make therapeutic decisions. Patients and payers (insurance) complete this ecosystem [24].

The following workflow diagram illustrates the multi-step process for implementing clinical pharmacogenomics:

Analytical and Computational Methods

A significant technical challenge in PGx is the functional interpretation of rare genetic variants. Genes involved in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) are highly variable, with tens of thousands of different single nucleotide variants (SNVs) and indels, over 98% of which are rare [30]. Characterizing these requires advanced methods:

- Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS): Facilitates comprehensive profiling of pharmacogenes. Specialized technologies like single-molecule real-time sequencing are needed for complex loci (e.g., CYP2D6, HLA) [30].

- Computational Prediction Tools: Tools like SIFT, PolyPhen2, and CADD use machine learning to predict the functional consequences of uncharacterized variants. However, their training on pathogenic datasets can limit accuracy for non-pathogenic pharmacogenomic variants [30].

- Experimental High-Throughput Characterization: Novel multiplexed assays allow for the simultaneous functional assessment of thousands of variants in vitro, generating crucial data to validate computational predictions [30].

The diagram below outlines the core process for interpreting genetic variants to guide drug therapy:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The advancement of pharmacogenomics relies on a suite of sophisticated reagents and analytical tools.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions in Pharmacogenomics

| Reagent/Material | Function in PGx Research |

|---|---|

| PCR Reagents | Amplifies specific DNA sequences for downstream analysis like sequencing or variant detection [27]. |

| Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) Libraries | Prepared genomic libraries allow for the massive parallel sequencing of entire genomes or targeted gene panels (e.g., ADME core panels) [30]. |

| Sanger Sequencing Reagents | Provides gold-standard validation for specific genetic variants discovered via NGS or other screening methods [27]. |

| TaqMan Assays & Genotyping Arrays | Enables high-throughput, targeted genotyping of known, common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [30]. |

| Nanopore Sequencing Kits | Facilitates long-read sequencing, which is critical for resolving complex genomic regions like CYP2D6 and HLA [30]. |

| Heterologous Expression Systems (e.g., Mammalian cells, Yeast) | Used for in vitro functional characterization of novel genetic variants in drug-metabolizing enzymes and transporters [30]. |

| Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM) Assays | Measures drug and metabolite concentrations in patient plasma, providing phenotypic data to correlate with genotype [30]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Components | Allows for precise gene editing in cell lines or model organisms to validate the functional impact of genetic variants [27]. |

| Mirificin | Mirificin, CAS:103654-50-8; 1228105-51-8, MF:C26H28O13, MW:548.497 |

| Acetyl Perisesaccharide C | Acetyl Perisesaccharide C|For Research |

The historical journey from Pythagoras's philosophical speculations to the modern genomic era underscores a fundamental shift in understanding life's instructions. The convergence of Mendelian genetics, molecular biology, and large-scale genome sequencing has given rise to the disciplined science of pharmacogenomics. Today, PGx is poised to transform clinical practice by moving from a reactive, one-size-fits-all treatment model to a preemptive, personalized approach. Future progress hinges on overcoming current challenges, including the need for broader education for healthcare providers, clearer reimbursement pathways for PGx testing, and the development of more robust, population-specific clinical guidelines. Furthermore, the integration of artificial intelligence and machine learning with large-scale biobank data promises to unlock deeper insights into the genetic underpinnings of drug response, ultimately fulfilling the promise of personalized medicine that is rooted in a history of scientific discovery spanning millennia [29] [30].

Evolutionary Perspectives on ADME Gene Polymorphism Development

The genetic variation in genes governing drug Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, and Excretion (ADME) represents a crucial interface between human evolutionary history and modern pharmaceutical science. This technical review examines the evolutionary forces—including natural selection, genetic drift, and population-specific adaptations—that have shaped the remarkable polymorphism observed in pharmacogenes. We synthesize evidence from population genetics, functional genomics, and clinical pharmacogenomics to demonstrate how evolutionary processes have created structured variation in ADME genes across human populations. This analysis provides a framework for understanding interindividual and interethnic variability in drug response, with significant implications for personalized medicine strategies in globally diverse populations. The integration of evolutionary perspectives into pharmacogenomic research promises to enhance drug safety and efficacy by enabling more precise targeting of therapeutic interventions.

The ADME gene family comprises a specialized set of genes encoding proteins responsible for the absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion of both exogenous compounds (including pharmaceuticals) and endogenous molecules. These genes include drug-metabolizing enzymes (DMEs) such as cytochrome P450 enzymes (CYPs), conjugating enzymes, and transporter proteins from the SLC and ABC families [31]. The evolutionary history of these genes reveals a complex interplay between environmental pressures, dietary changes, and pathogen exposures that have shaped their polymorphic landscape across human populations.

From an evolutionary perspective, ADME genes exhibit unusual characteristics that make them particularly susceptible to polymorphic variation. Unlike genes encoding critical structural or metabolic pathway components, many ADME genes show relaxed evolutionary constraints, allowing accumulation of functional variants without catastrophic fitness consequences [32]. This tolerance for variation has created a genetic architecture ideal for rapid adaptation to changing environments, especially as human populations dispersed globally and encountered novel chemical environments, dietary components, and disease pressures.

The Remote Sensing and Signaling Hypothesis provides a theoretical framework for understanding the broader physiological roles of ADME genes beyond drug processing [31]. This hypothesis posits that ADME genes form an interactive network regulating inter-organ communication via metabolites, signaling molecules, antioxidants, gut microbiome products, and uremic toxins. This broader physiological function helps explain why these genes have been subject to such varied selective pressures throughout human evolution.

Evolutionary Mechanisms Shaping ADME Polymorphisms

Natural Selection and Adaptive Evolution

Natural selection has operated on ADME genes through multiple mechanisms, with positive selection acting on standing variation as a prominent force. Genomic analyses have revealed that positive selection from standing variation has exerted moderate but persistent pressure on ADME genes in Eurasian populations, driving adaptive alleles to high frequencies over prolonged evolutionary history [33]. The timing of these selective events often coincides with major human migrations and ecological transitions, suggesting environmental factors as key drivers.

Specific examples of adaptation illustrate these mechanisms:

CYP2D6 gene duplication: In Northeast Africa approximately 10,000-5,000 years ago, strong positive selection favored survival of individuals carrying multiple copies of the CYP2D6 gene, potentially enhancing detoxification capabilities for plant alkaloids during periods of dietary diversification and starvation [34]. These duplication alleles subsequently spread through migration into Mediterranean regions but not to Asia or West Africa, creating distinct geographic patterns of variation.

ADH1B*48His (rs1229984): This well-documented polymorphism shows striking differentiation between Tibetan and other populations (FST = 0.646 between Tibetan and Lic populations) [33]. The adaptation to subsistence lifestyle following Neolithic agriculture has been proposed as the evolutionary driver, demonstrating how cultural innovations can reshape genetic variation.

PPARD locus: Analysis of contrastive sequence signatures between both sides of a recombination spot provides evidence for a selective sweep at the PPARD locus through genetic hitchhiking effect [33]. The onset of this adaptation coincided with early out-of-Africa migration of modern humans and persisted throughout their evolutionary history, suggesting prolonged selective pressure.

Population Dynamics and Genetic Drift

Human demographic history has profoundly influenced the distribution of ADME variants across populations. Founder effects, population bottlenecks, and migration patterns have all contributed to the structured variation observed in modern populations. The accumulation of rare variants—which account for over 90% of the overall genetic variability in pharmacogenes—has been particularly influenced by population-specific genetic drift [32].

Population genetic studies demonstrate that Amerindian populations show the most distinct ADME genetic profile compared to other continental groups (mean FST = 0.09917) [35]. This distinctiveness reflects both the founder effects during the peopling of the Americas and subsequent genetic isolation. Similarly, studies of African populations reveal substantial population structuring at CYP450 genes, associated with intra-African differences in responses to drugs used for infectious disease treatment [36].

The persistence of rare variants in population isolates represents a particularly important phenomenon for pharmacogenomics. Each individual harbors on average 40.6 putatively functional variants in ADME genes, with rare variants accounting for 10.8% of these [32]. These rare variants collectively contribute to the "missing heritability" in drug response traits not explained by common polymorphisms.

Table 1: Evolutionary Mechanisms and Their Impact on ADME Gene Variation

| Evolutionary Mechanism | Impact on ADME Genes | Representative Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Positive Selection | Increases frequency of adaptive alleles; creates geographic variation | CYP2D6 duplication in Northeast Africa; ADH1B in East Asians |

| Genetic Drift | Causes random fluctuations in allele frequency; prominent in small populations | Rare variant accumulation in population isolates; Amerindian distinctiveness |

| Population Bottlenecks | Reduces genetic diversity; increases frequency of founder variants | Reduced diversity in non-African populations; distinctive Amerindian profile |

| Migration and Admixture | Creates clinal variation and novel combinations of variants | East-West stratification in Eurasian populations; admixed population variability |

Population-Specific Variation in ADME Genes

Continental Patterns of Variation

ADME genes exhibit striking differences in allele frequencies across major population groups, reflecting their distinct evolutionary histories. These patterns have profound implications for global drug development and implementation of pharmacogenomic testing across diverse populations.

African populations display exceptional diversity in CYP450 genes, with numerous population-specific variants affecting drug metabolism. For example, CYP2C95 and CYP2C911 are predominantly found in African populations (1-3% and 1-23% frequency respectively) and are associated with excessive anticoagulation risk in African-American patients [36]. The CYP3A4*1B variant shows particularly high frequency in African populations (66-86%) compared to Europeans (2-4%) or East Asians (0%), contributing to population-specific metabolism of numerous pharmaceuticals [36].

Amazonian Amerindian populations demonstrate a unique ADME genetic profile characterized by significantly different allelic frequencies and genotype distributions in multiple markers compared to African, European, American, and Asian populations [35]. This distinctiveness highlights the importance of including under-represented populations in pharmacogenomic studies to ensure equitable application of precision medicine approaches.

East Asian populations show characteristic patterns of variation, including higher frequencies of CYP2C19 poor metabolizer alleles (*2 and *3) compared to other populations [36]. The extensive genetic architecture studies in Chinese populations reveal a north-south cline in ADME variation, with three major groups—northern minorities (Uygur, Mongolian, Tibetan), Han Chinese, and southern minorities—primarily reflecting geographical and historical relationships [33].

Functional Consequences of Population Variation

The population-specific variation in ADME genes has direct consequences for drug metabolism phenotypes and clinical outcomes:

CYP2D6 variation: Polymorphisms and haplotypes in CYP2D6 contribute to variable metabolism of approximately 25% of clinically administered drugs [36]. The gene is subject to copy number variations (CNVs), with individuals carrying multiple functional copies exhibiting ultrarapid metabolism that prevents achievement of therapeutic drug concentrations at standard dosages.

CYP2C19 variation: The CYP2C19*2 allele (no detectable enzyme levels) shows substantial frequency variation across populations (11-21% in Africans, 13-14% in American populations, 32-36% in Asians, and 7-22% in Europeans) [36]. This variation influences response to numerous drugs including clopidogrel, proton pump inhibitors, and antidepressants.

CYP3A5 variation: The CYP3A5*3 allele (reduced/undetectable expression) shows dramatic frequency differences, occurring in 93-96% of Europeans but only 4-81% of Africans [36]. This variation affects metabolism of tacrolimus and other important medications.

Table 2: Population Frequencies of Clinically Important ADME Variants

| Gene | Variant | Effect | African Frequency | European Frequency | East Asian Frequency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C9 | *2 | Reduced function | 7% | 9-16% | 1% |

| CYP2C9 | *3 | Reduced function | 2-3% | 5-11% | 2-6% |

| CYP2C9 | *5 | Reduced function | 1-3% | 0% | 0% |

| CYP2C19 | *2 | No function | 11-21% | 7-22% | 32-36% |

| CYP2C19 | *3 | No function | 1% | 0% | 5-6% |

| CYP2D6 | *17 | Reduced function | 20-35% | 1-3% | 0-1% |

| CYP3A4 | *1B | Increased function | 66-86% | 2-4% | 0% |

| CYP3A5 | *3 | Reduced function | 4-81% | 93-96% | 69-74% |

| TPMT | *3A | Reduced function | 1-3% | 3-5% | 1-2% |

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Population Genetics and Genotyping Methods

The dissection of evolutionary patterns in ADME genes relies on sophisticated genotyping and analytical approaches. High-throughput genotyping technologies have enabled comprehensive characterization of ADME variation across diverse populations. The DMET (Drug Metabolism Enzymes and Transporters) platform represents one such approach, allowing simultaneous assessment of multiple polymorphisms in ADME genes [37].

Standardized protocols for ADME genotyping typically involve:

- DNA extraction from peripheral blood using commercial kits (e.g., Biopur Mini Spin Plus) with quality assessment via spectrophotometry (e.g., NanoDrop 1000) [35]

- Genotyping using technologies such as TaqMan OpenArray customized assays run on platforms like QuantStudio 12K Flex Real-Time PCR systems [35]

- Quality control including Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium testing and exclusion of markers deviating from expected distributions [35]

For population genetics analyses, key methodologies include:

- FST (fixation index) calculations to measure population differentiation at each locus [35] [33]

- Multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis to visualize genetic relationships between populations [35]

- STRUCTURE analysis to identify ancestral components and admixture patterns [33]

- Linkage disequilibrium (LD) analysis to identify regions with evidence of selective sweeps [33]

Detecting Natural Selection in ADME Genes

Several specialized approaches have been developed to identify signatures of natural selection in ADME genes:

Contrastive sequence signature analysis: Examining differences in genetic variation patterns between both sides of recombination spots can reveal selective sweeps through genetic hitchhiking effects [33]

Haplotype-based tests: Extended haplotype homozygosity and related approaches detect unusually long haplotypes indicative of recent positive selection

Integration with functional genomic data: Combining population genetic data with gene expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) analyses helps connect adaptive variants to their functional consequences [33]

Cross-tissue co-expression network analysis: Identifying coordinated expression patterns of ADME genes across tissues (e.g., gut-liver-kidney axis) provides insights into their functional integration and evolutionary constraints [31]

Diagram 1: Experimental Workflow for Evolutionary Analysis of ADME Genes. This workflow outlines the key steps in characterizing evolutionary patterns in ADME genes, from sample collection through functional validation.

Table 3: Essential Research Resources for ADME Evolutionary Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Application/Function |

|---|---|---|

| Genotyping Platforms | DMET (Drug Metabolism Enzymes and Transporters) microarray [37] | Simultaneous interrogation of multiple ADME polymorphisms |

| TaqMan OpenArray Genotyping Technology [35] | Customized SNP genotyping with high throughput capability | |

| Bioinformatic Tools | ADME-optimized prediction framework [32] | Computational functionality prediction for pharmacogenetic variants |

| STRUCTURE software [33] | Population structure analysis and ancestry estimation | |

| Arlequin v.3.5 [35] | Population genetics analyses including FST calculations | |

| Reference Databases | 1000 Genomes Project [35] [33] | Global genetic variation reference for population comparisons |

| Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) [32] | Database of exonic variants from large-scale sequencing projects | |

| PharmGKB [38] [35] | Curated knowledge resource for pharmacogenomic associations | |

| Analytical Approaches | Multi-dimensional Scaling (MDS) [35] [33] | Visualization of population relationships based on genetic distances |

| Cross-tissue co-expression network analysis [31] | Identification of functionally connected ADME gene networks | |

| Loss-of-function intolerance scoring [32] | Assessment of evolutionary constraints on pharmacogenes |

Implications for Personalized Medicine and Drug Development

Clinical Translation of Evolutionary Insights

Understanding the evolutionary forces that shaped ADME variation provides a crucial foundation for implementing pharmacogenomics in clinical practice. The differential distribution of pharmacogenetic variants across populations has direct implications for drug safety and efficacy across diverse patient groups. Regulatory agencies have recognized this importance, with the FDA maintaining a table of pharmacogenomic biomarkers in drug labeling that includes numerous ADME-related genes [14].

Clinical implementation frameworks must account for evolutionary insights in several ways:

Population-specific dosing guidelines: For drugs like warfarin, clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium (CPIC) guidelines incorporate genetic factors that show population variation, including CYP2C9 and VKORC1 variants [38]

Rare variant consideration: Next-generation sequencing approaches capture rare variants that contribute substantially to functional variability in many pharmacogenes [32]

Admixed population strategies: Populations with recent admixture, such as African Americans and Latin Americans, require special consideration due to the complex interplay of genetic variants from different ancestral backgrounds [33]

Regulatory and Implementation Considerations

The integration of evolutionary perspectives into drug development and clinical practice requires addressing several challenges:

Database representation: Current pharmacogenetic databases remain skewed toward European-ancestry populations, limiting understanding of variation in other groups [35]

Biomarker validation: Biomarkers must be validated across diverse populations to ensure generalizability, considering the high population specificity of many ADME variants [37]

Clinical decision support: Electronic health record integration of pharmacogenetic data must account for population-specific allele effects and interpretation [38]

The overlap between FDA pharmacogenomic labeling and CPIC guidelines provides a framework for implementation. Analysis reveals that among ADME gene-drug pairs, 74% are classified as "actionable," 15% as "informative," 9% as "testing recommended," and 2% as "testing required" [38]. CYP2D6 represents the most prevalent ADME gene in FDA labeling, reflecting its importance in numerous drug metabolism pathways.

Diagram 2: Evolutionary Pathways from Environmental Pressures to Clinical Implications. This diagram illustrates the conceptual pathway linking environmental selective pressures through evolutionary mechanisms to genetic outcomes in ADME genes and their subsequent clinical implications for personalized medicine.

The evolutionary perspective on ADME gene polymorphisms provides a foundational framework for understanding the genetic architecture of drug response variability. The interplay between natural selection, genetic drift, and human demographic history has created a structured landscape of variation that differs substantially across populations. This evolutionary legacy has direct consequences for drug development, clinical trial design, and implementation of personalized medicine across diverse global populations.

Future research directions should include:

Expanded diversity in genomic studies: Deliberate inclusion of under-represented populations in pharmacogenomic studies to capture the full spectrum of ADME variation [35]

Integration of rare variants: Development of computational frameworks that incorporate both common and rare variants into drug response predictions [32]

Functional characterization: Systematic functional assessment of population-specific variants to determine their clinical relevance [37]

Evolutionary-aware clinical guidelines: Development of prescribing guidelines that incorporate population genetic principles while avoiding oversimplified racial categorization

The growing understanding of ADME gene evolution promises to enhance drug safety and efficacy by enabling more precise targeting of therapeutic interventions. By acknowledging the evolutionary forces that shaped pharmacogenetic variation, researchers and clinicians can better navigate the complex interplay between human genetic diversity and pharmaceutical interventions in an increasingly globalized healthcare environment.

Clinical Implementation and Therapeutic Applications: From Biomarker Discovery to Treatment Personalization

The efficacy and toxicity of cancer therapeutics are governed by a complex interplay of two distinct genetic systems: the germline genome, an individual's inherited genetic blueprint present in every cell, and the somatic genome, comprising acquired mutations found exclusively within tumor cells [39]. Germline variants influence drug metabolism, transport, and mechanism of action in all tissues, representing a systemic determinant of therapeutic response [40] [1]. In contrast, somatic mutations drive oncogenesis and can create tumor-specific dependencies that determine susceptibility to targeted therapies [39] [41]. The emerging paradigm in precision oncology recognizes that comprehensive drug response prediction requires integrated analysis of both genetic systems, as their contributions to treatment outcomes can be complementary and sometimes of comparable magnitude [40]. This whitepaper examines the distinct characteristics, detection methodologies, and predictive values of germline and somatic biomarkers, framing their integration as an essential component of pharmacogenomics-driven personalized medicine.

Fundamental Distinctions Between Germline and Somatic Variants

Biological Origin and Transmission

Germline and somatic variants differ fundamentally in their origin, distribution throughout the body, and implications for cancer risk and treatment.

Germline variants originate in reproductive cells (sperm or egg) and are incorporated into every cell of the offspring's body following conception [39]. These variants are heritable and can be passed to subsequent generations, following Mendelian inheritance patterns. When pathogenic, germline variants in cancer predisposition genes such as BRCA1, BRCA2, and Lynch syndrome-associated genes (MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, PMS2) confer increased lifetime cancer risk [39] [42].

Somatic variants, in contrast, are acquired throughout an individual's lifetime due to environmental exposures (tobacco, ultraviolet radiation, chemicals), replication errors, or other cellular insults [39]. These mutations are confined to specific cell populations and their progeny, are not present in all body cells, and cannot be transmitted to offspring. Somatic mutations drive carcinogenesis by activating oncogenes or inactivating tumor suppressor genes within specific tissues.

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Germline versus Somatic Variants

| Characteristic | Germline Variants | Somatic Variants |

|---|---|---|

| Origin | Inherited from parents | Acquired during lifetime |

| Transmission | Heritable across generations | Not heritable |

| Cell Distribution | Present in every nucleated body cell | Confined to specific cell populations/tumors |

| Contribution to Cancer | ~5-10% of all cancers [39] | Majority of cancers (sporadic) |

| Temporal Stability | Constant throughout life | Evolve over time (temporal heterogeneity) |

| Detection Method | Blood, saliva, or buccal samples [39] | Tumor tissue or liquid biopsy [39] |

Clinical Indicators for Genetic Testing

Specific clinical and familial patterns should raise suspicion for germline versus somatic origins of cancer susceptibility:

Indicators of potential germline predisposition include [39]:

- Early-onset cancer (e.g., breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancer diagnosed before age 50)

- Multiple primary cancers in one individual or bilateral cancer in paired organs

- Rare cancers (e.g., male breast cancer, ovarian cancer, pancreatic cancer)

- Strong family history with evidence of autosomal dominant inheritance

- Specific tumor characteristics (e.g., triple-negative breast cancer, microsatellite instability)

- Presence of premalignant conditions (e.g., ≥20 colorectal adenomatous polyps)

Somatic mutations are suspected in sporadic cancers without the above patterns, particularly when associated with known environmental risk factors or advancing age [39].

Predictive Contributions to Drug Response

Germline Biomarkers: Systemic Determinants of Drug Metabolism and Toxicity

Germline variants influence drug response through multiple mechanisms, primarily affecting drug metabolism, transport, and targets. These systemic genetic factors can produce therapeutic outcomes ranging from lack of efficacy to severe adverse reactions.

Table 2: Germline Biomarkers with Clinical Utility in Oncology and Beyond

| Biomarker/Gene | Drug/Therapeutic Class | Effect/Mechanism | Clinical Utility |

|---|---|---|---|

| CYP2C19 | Clopidogrel [29] | Reduced activation in poor metabolizers | FDA label warning; consider alternative antiplatelets |

| CYP2D6 | Tamoxifen [43] | Reduced activation in poor metabolizers | Consider alternative endocrine therapy |

| DPYD | 5-Fluorouracil [40] | Increased toxicity due to reduced clearance | Dose adjustment or drug avoidance |

| HLA-B*15:02 | Carbamazepine [1] | Increased risk of severe cutaneous adverse reactions (SCARs) | Pre-treatment screening in high-risk populations |

| BRCA1/BRCA2 | PARP inhibitors [40] [42] | Synthetic lethality in homologous repair-deficient cells | Predictive biomarker for PARP inhibitor efficacy |

Recent evidence demonstrates that germline variants contribute substantially to variation in drug susceptibility. A systematic analysis of 993 cancer cell lines and 265 drugs revealed that germline contributions to drug susceptibility can be as large or larger than effects from somatic mutations [40]. For the HSP90 inhibitor 17-AAG, germline variants explained 5.1% of response variance, while somatic mutations showed no predictive power [40].

Somatic Biomarkers: Tumor-Specific Therapeutic Targets

Somatic mutations create therapeutic vulnerabilities that can be exploited with targeted therapies. These biomarkers typically inform on-target drug effects rather than systemic metabolism.

Table 3: Somatic Biomarkers with Clinical Utility in Oncology

| Biomarker | Drug/Therapeutic Class | Effect/Mechanism | Clinical Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| BRAF V600E | Vemurafenib, Dabrafenib [44] | Direct inhibition of mutated BRAF kinase | Melanoma, colorectal cancer |

| EGFR mutations | Gefitinib, Erlotinib, Osimertinib | Inhibition of mutated EGFR kinase | Non-small cell lung cancer |

| BRCA1/2 somatic | PARP inhibitors [42] | Synthetic lethality | Ovarian, breast, pancreatic cancer |

| Microsatellite Instability (MSI-H) | Immune checkpoint inhibitors [42] | Enhanced neoantigen presentation | Multiple solid tumors |

| HER2 amplification | Trastuzumab, HER2-targeted therapies | Antibody-mediated inhibition of HER2 signaling | Breast, gastric cancers |

Notably, some therapeutic biomarkers can originate from either germline or somatic alterations. For example, PARP inhibitor sensitivity occurs with both germline and somatic BRCA1/2 mutations, though approximately 35% of germline variants are not detected by somatic testing alone [45], highlighting the importance of comprehensive genetic assessment.

Methodological Approaches for Biomarker Discovery and Validation

Experimental Designs for Dissecting Germline and Somatic Contributions

Systematic approaches have been developed to quantify the relative contributions of germline and somatic variants to drug response: