Strategies for Minimizing Non-Specific Binding in Biochemical Assays: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Non-specific binding (NSB) is a pervasive challenge in biochemical assays that can compromise data accuracy, lead to false positives, and hinder drug development.

Strategies for Minimizing Non-Specific Binding in Biochemical Assays: A Comprehensive Guide for Researchers

Abstract

Non-specific binding (NSB) is a pervasive challenge in biochemical assays that can compromise data accuracy, lead to false positives, and hinder drug development. This article provides researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals with a comprehensive framework to understand, mitigate, and troubleshoot NSB. Covering foundational principles to advanced validation techniques, we explore the physicochemical roots of NSB, detail practical methodological optimizations, present systematic troubleshooting protocols, and outline rigorous validation standards to ensure assay reproducibility and reliability.

Understanding the Enemy: The Core Principles and Causes of Non-Specific Binding

Non-specific binding (NSB) is a fundamental challenge that researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals encounter across various biochemical assays. It refers to the occurrence of an antibody or analyte binding to unintended targets, such as proteins, receptors, or sensor surfaces, rather than specifically to its intended target [1] [2]. This phenomenon is not correlated with the assay's intended specificity and can lead to inaccurate data, false positives, false negatives, and ultimately, misinterpretation of experimental results [1] [3]. For the IVD industry and drug discovery pipelines, NSB can negatively impact proper diagnosis, treatment decisions, and the validation of potential drug candidates [1] [4]. This guide provides troubleshooting advice and FAQs to help you identify, minimize, and correct for NSB in your experiments.

Troubleshooting Guides

Diagnosing the Source of Non-Specific Binding

The first step in troubleshooting is identifying the likely cause of the high background or false signal in your assay.

Common Causes and Solutions Table

| Cause of Non-Specific Binding | Symptoms in Experiment | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Insufficient Blocking [1] [5] | High background across the membrane or plate. | Optimize blocking buffer; use protein blockers (e.g., BSA, serum) or commercial stabilizer/blocker reagents [1] [6]. |

| Antibody Concentration Too High [7] [8] | High background and diffuse, smeared bands/signals. | Perform an antibody titration study to find the optimal dilution [7]. |

| Fc Receptor Interactions [1] [7] | High background in flow cytometry with immune cells (neutrophils, monocytes, macrophages). | Use an Fc blocking reagent or include normal serum from the host species of the secondary antibody [7]. |

| Hydrophobic / Charge Interactions [5] | High background in label-free assays like SPR. | Add non-ionic surfactants (e.g., Tween 20) or increase salt concentration in buffers [5]. |

| Non-Viable Cells [7] | Cell clumping and high background in flow cytometry. | Use a viability dye (e.g., 7-AAD, PI) to exclude dead cells during analysis [7]. |

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing NSB based on the symptoms you observe.

Experimental Protocol: Titrating Antibodies to Minimize NSB

This is a fundamental protocol for optimizing any immunoassay (Western blot, flow cytometry, ELISA) to reduce NSB caused by excessive antibody.

Objective: To determine the optimal dilution of a primary antibody that provides a strong specific signal with minimal background noise.

Materials:

- Primary antibody

- Appropriate blocking buffer (e.g., 5% BSA or non-fat dry milk in TBST)

- Positive control sample (known to express the target)

- Negative control sample (known not to express the target)

- All other standard assay components (secondary antibody, detection reagents, etc.)

Method:

- Prepare a dilution series of your primary antibody. A typical starting range is from the manufacturer's recommended dilution to a dilution 4-8 times more dilute. For example, if the recommended dilution is 1:1000, prepare dilutions of 1:1000, 1:2000, 1:4000, and 1:8000.

- Run your assay (e.g., Western blot, flow cytometry staining) using the standard protocol, applying the different antibody dilutions to identical replicate samples.

- Compare the signals between the positive and negative controls for each dilution.

- Select the optimal dilution as the one that yields the strongest specific signal in the positive control with the lowest background in the negative control [7] [8]. This dilution provides the best signal-to-noise ratio.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between specific and non-specific binding? Specific binding is the high-affinity interaction between a bioreceptor (e.g., antibody) and its intended target (e.g., protein epitope). Non-specific binding is a lower-affinity interaction with unintended sites, such as assay surfaces, Fc receptors, or other proteins with vaguely similar epitopes [1] [2]. Research using chemiresistive biosensors has shown that these two types of binding can produce distinct electrical response profiles (e.g., negative ΔR for specific vs. positive ΔR for non-specific), offering a potential way to decouple them [3].

Q2: How can non-specific binding be prevented in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) experiments? SPR is particularly susceptible to NSB from charge and hydrophobic interactions. Key strategies include [5]:

- Adjust buffer pH: Use a pH that neutralizes the charge of your analyte or sensor surface.

- Use additives: Include bovine serum albumin (BSA, ~1%) or a mild non-ionic surfactant like Tween 20 (~0.05%) in the running buffer.

- Increase ionic strength: Adding salt (e.g., 150-200 mM NaCl) can shield charge-based interactions.

Q3: My Western blot has a high background. What are the first things I should check? Start with these three steps [9]:

- Check your blocking: Ensure you are using a fresh, effective blocking agent (e.g., 5% BSA or milk) for an adequate time.

- Optimize antibody concentration: Overly concentrated antibody is a very common cause. Perform a titration.

- Increase wash stringency: Ensure you are using an appropriate wash buffer (e.g., TBST) and performing enough wash steps after antibody incubations.

Q4: Can non-specific binding come from the secondary antibody? Yes. The quality of the secondary antibody is critical. Always run a control where the primary antibody is omitted. Any signal in this control is due to non-specific binding of the secondary antibody or other components in the detection system [8].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents to Combat NSB

Having the right reagents is essential for developing robust assays. The table below summarizes key solutions used to minimize non-specific binding.

Research Reagent Solutions for Minimizing NSB

| Reagent Category | Example Products | Primary Function & Application |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Blockers | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), Non-fat Dry Milk, Normal Serum [5] [6] [7] | Saturate unused binding sites on surfaces (e.g., membranes, plates, cells) to prevent non-specific protein adsorption. |

| Commercial Stabilizers/Blockers | StabilGuard, StabilCoat, StabilBlock, LowCross-Buffer [1] [2] | Specialty formulations designed to simultaneously stabilize immobilized proteins and block against NSB, often in a single step. |

| Non-Ionic Surfactants | Tween 20 [5] | Disrupt hydrophobic interactions between analytes and surfaces by reducing surface tension. Added to wash and incubation buffers. |

| Fc Receptor Blockers | Recombinant Fc Block, Purified Ig [7] | Bind specifically to Fc receptors on immune cells, preventing antibodies from attaching non-specifically via their Fc region. |

| Assay/Sample Diluents | MatrixGuard, Surmodics Assay Diluent [1] | Specialized diluents designed to block matrix interferences in complex biological samples (e.g., serum, plasma) to reduce false positives. |

| BAY-474 | BAY-474, MF:C17H15N5, MW:289.33 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| YM-53601 free base | YM-53601 free base, CAS:182959-28-0, MF:C21H21FN2O, MW:336.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Core Concepts: Understanding the Three Factors of NSB

Nonspecific binding (NSB) is a common challenge in biochemical assays, where analytes adsorb to surfaces through non-covalent interactions, compromising data accuracy and reliability. The phenomenon is primarily governed by three interconnected factors: the properties of the solid surface, the composition of the solution, and the inherent characteristics of the analyte itself [10] [11].

1. Solid Surfaces The material composition of the surfaces that the solution contacts is a primary determinant of NSB. Different materials present distinct functional groups that drive adsorption through various mechanisms [10] [11]:

- Glassware: Surfaces are abundant in silanol groups that acquire a negative charge, making them prone to binding positively charged molecules via ionic interactions [10].

- Plastic Consumables (e.g., Polypropylene, Polystyrene): These materials are rich in hydrophobic groups, leading to significant binding of hydrophobic molecules [10] [11].

- Metal Surfaces (e.g., in liquid chromatography systems): Metal cations can readily bind anionic molecules through ionic interactions [10] [11].

2. Solution Composition The environment in which the analyte is dissolved greatly influences its dissociation state, solubility, and potential for NSB [10]:

- pH: Affects the ionization state of both the analyte and the solid surface, thereby influencing electrostatic interactions [10].

- Buffer Salts: Can attach to binding sites on solid surfaces, potentially blocking them, or influence interactions via the Hofmeister series [10] [12].

- Proteins and Lipids: Components like those found in biological matrices (e.g., plasma) can bind to analytes or surfaces, sometimes competitively reducing NSB to container walls [10] [11].

- Organic Solvents and Additives: Can alter the solubility of the analyte and the properties of the solvation layer [12].

3. Analyte Properties The physicochemical nature of the compound itself dictates its primary mode of interaction with surfaces [10] [11]:

- Hydrophobic Compounds: Rich in non-polar groups (e.g., alkanes, aromatic rings); primarily bind to hydrophobic surfaces.

- Hydrophilic Compounds: Contain easily dissociable, charged groups; primarily bind via ionic interactions and hydrogen bonding.

- Amphiphilic Compounds: Possess both hydrophobic and hydrophilic regions (e.g., peptides, cationic lipids), making them particularly prone to NSB through multiple mechanisms [11].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My low-concentration analyte is adsorbing to the walls of my plastic sample tubes, leading to low recovery. What can I do? This is a classic issue of NSB to consumables, especially for hydrophobic or amphiphilic analytes in low-protein matrices like urine or cerebrospinal fluid [11].

- Solution: Use low-adsorption consumables specifically designed for proteins or nucleic acids [10] [11]. Alternatively, add a small amount of a suitable surfactant (e.g., 0.01-0.1% Tween) to the solution. The surfactant will compete for binding sites and form a protective layer around the analyte [11]. Adding a carrier protein like Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) can also compete for surface binding sites [10] [13].

Q2: I observe peak tailing and significant carryover during LC-MS analysis. What is the likely cause and how can I address it? This typically indicates NSB within the chromatographic system, often on the metal fluidic path or the stationary phase of the column [10] [11].

- Solution:

- Passivate the system: Use low-adsorption liquid phase systems and columns that have treated surfaces to minimize interactions [11].

- Modify the mobile phase: Adjust the ionic strength or pH to weaken analyte-surface interactions [10]. For analytes that chelate metals (e.g., phosphorylated or nucleic acid compounds), add a chelating agent like EDTA to the mobile phase [11].

- Increase column temperature to reduce hydrophobic interactions [10].

Q3: Does a higher binding affinity (lower KD) always lead to a better assay? Not necessarily. While a low KD (high affinity) is often sought after, it is only "better" in the context of your target concentration [14]. An affinity reagent with a KD that is too low will be saturated at very low target concentrations, limiting the dynamic range of your assay. The useful quantitative range for a binding reagent is conventionally considered to be between 0.11 and 9.0 times its KD. Therefore, you should match the KD of your reagent to the expected concentration of your target [14].

Troubleshooting Guide Table

| Problem Scenario | Primary Factor Involved | Recommended Mitigation Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Low analyte recovery from sample tubes | Solid Surface, Analyte Properties | - Use low-adsorption consumables [11].- Add surfactants (e.g., Tween) [11].- Add a carrier protein (e.g., BSA) [10] [13]. |

| Peak tailing & carryover in HPLC/UPLC | Solid Surface, Solution Composition | - Use a low-adsorption/passivated column and system [11].- Adjust mobile phase ionic strength or pH [10].- Add a chelating agent (e.g., EDTA) [11].- Increase column temperature [10]. |

| High background in plate-based assays (e.g., ELISA) | Solid Surface, Solution Composition | - Optimize blocking agents (e.g., BSA, casein) [13].- Include control wells without target analyte [13].- Optimize wash buffer composition (e.g., add mild detergents) [13]. |

| Inconsistent results in SPR biosensors | Solid Surface, Solution Composition | - Regenerate and condition the sensor chip surface properly [13].- Include negative controls with irrelevant molecules [13].- Purify sample to remove contaminants [13].- Optimize buffer pH and ionic strength [13]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Investigation of Nonspecific Binding to Consumables

Purpose: To diagnose and quantify the degree of NSB for a new analyte to various container materials. Background: The larger the contact surface area and the longer the contact time, the more severe adsorption becomes. This protocol uses this principle to investigate NSB [11].

Materials:

- Stock solution of the analyte

- Test matrices (e.g., buffer, urine, plasma)

- Different types of consumables (e.g., polypropylene, polystyrene, glass, low-adsorption tubes)

- Surfactants or carrier proteins (e.g., 1% BSA solution, 0.1% Tween 20)

Method:

- Prepare Solutions: Dilute the analyte to a relevant concentration in the desired matrix.

- Surface Area Test: Aliquot the same volume of solution into containers of different sizes (e.g., 0.5 mL in a 0.5 mL tube vs. a 2.0 mL tube). The larger surface-area-to-volume ratio will exacerbate binding [11].

- Material Comparison: Aliquot the solution into different containers of the same size but made of different materials (e.g., standard polypropylene vs. low-adsorption polypropylene).

- Desorption Agent Test: Add potential desorption agents (e.g., 0.1% Tween 20 or 1% BSA) to the solution and aliquot into the problematic container material.

- Incubate: Allow all samples to incubate for a time representative of your experimental storage or processing (e.g., 1 hour at room temperature).

- Analyze: Measure the recovered concentration of the analyte using your analytical method (e.g., HPLC, MS). A significant difference in recovery between containers or conditions indicates NSB.

Protocol 2: Mitigating NSB in Chromatographic Analysis of Nucleic Acid Drugs

Purpose: To achieve symmetric peaks and high recovery for nucleic acid analytes, which are prone to NSB with metal surfaces. Background: Nucleic acids, especially those with phosphorothioate backbones, are amphoteric and can chelate metal ions, leading to strong adsorption on stainless steel surfaces [11].

Materials:

- Nucleic acid analyte

- Mobile phases A and B

- EDTA disodium salt

- Low-adsorption chromatographic column (e.g., with passivated metal hardware and specially modified silica)

- Standard C18 column (for comparison)

Method:

- Mobile Phase Preparation: Add 0.1 mM EDTA to both mobile phases to chelate free metal ions [11].

- System Configuration: Install a low-adsorption liquid chromatography system or, at a minimum, use a low-adsorption column.

- Column Comparison: Inject the nucleic acid sample onto both a standard column and the low-adsorption column using the EDTA-supplemented mobile phase.

- Evaluation: Compare chromatographic peak shape, signal intensity, and carryover between the two setups. The low-adsorption system with EDTA should yield more symmetrical peaks and a significantly higher signal (up to 10-fold improvements have been reported) [11].

Visualizations

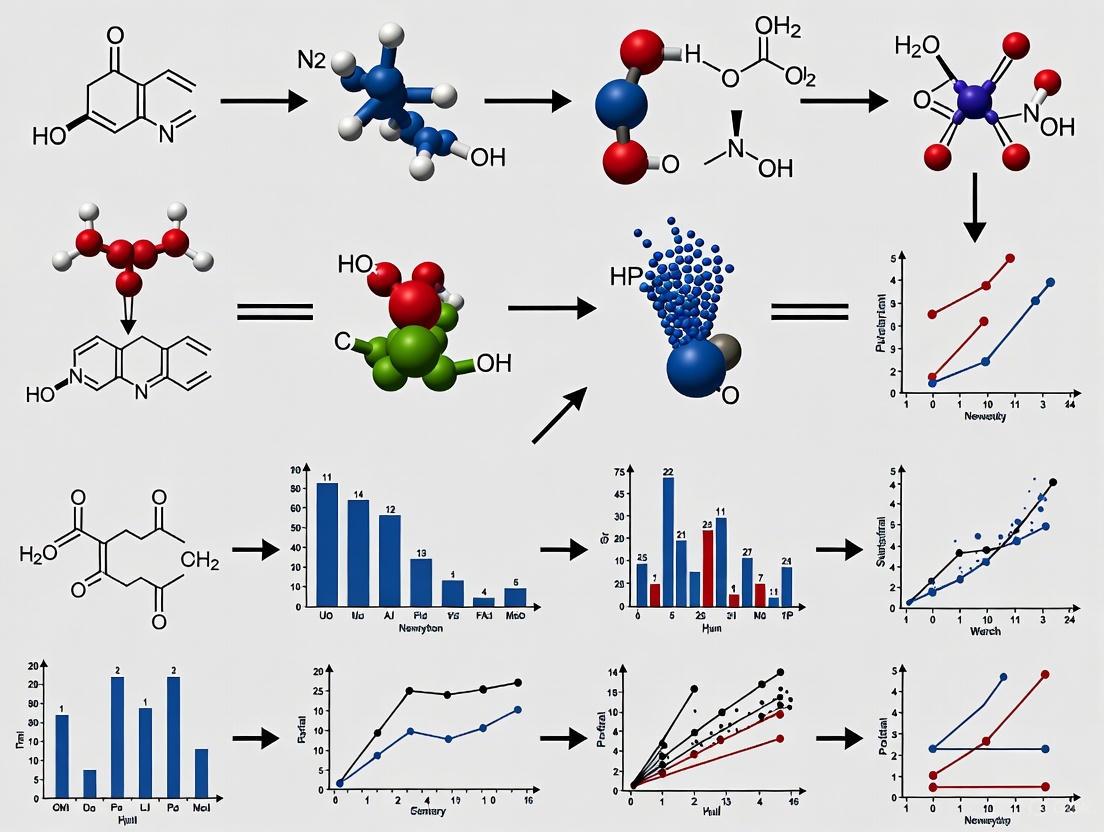

Diagram 1: Systematic NSB Troubleshooting Logic

Diagram 2: Three-Factor Model of Nonspecific Binding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Common Reagents for Controlling Nonspecific Binding

| Reagent Category | Examples | Primary Function & Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Blocking Agents | BSA, Casein, Non-fat dry milk | Cover unbound sites on solid surfaces (e.g., assay plates, sensor chips) with an inert protein, preventing subsequent NSB of the analyte [13]. |

| Surfactants | Tween 20, Triton X-100, CHAPS | Reduce hydrophobic interactions by forming a protective layer around the analyte or coating the surface. Can be ionic (SDS), non-ionic (Tween), or amphoteric (CHAPS) [11]. |

| Carrier Proteins | Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Added to analyte solutions (especially in low-protein matrices) to compete for surface binding sites, thereby protecting the analyte from NSB [10] [11]. |

| Chelating Agents | EDTA, EGTA | Bind to free metal ions in solution and passivate metal surfaces in liquid chromatography systems, crucial for preventing NSB of metal-chelatting analytes like nucleic acids and phosphorylated compounds [11]. |

| Low-Adsorption Consumables | Protein Low-Bind Tubes, Plates | Consumables manufactured with a proprietary polymer treatment that creates a hydrophilic, neutral surface, minimizing both ionic and hydrophobic interactions [10] [11]. |

| Specialized Chromatography | Low-Adsorption Columns, Inert Liners | HPLC/UPLC columns and system components with passivated metal surfaces (e.g., PEEK-silanced, MaxPeak) to minimize interactions with challenging analytes [11]. |

| PXS-5505 | PXS-5505, CAS:2409963-83-1, MF:C13H13FN2O2S, MW:280.32 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Phortress free base | Phortress free base, CAS:741241-36-1, MF:C20H23FN4OS, MW:386.5 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Non-specific binding (NSB) is a pervasive challenge in biochemical assays, capable of undermining the accuracy and reliability of experimental data. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding and mitigating NSB is critical for ensuring the validity of results, from early-stage discovery to diagnostic applications. At its core, NSB is frequently driven by fundamental molecular forces—hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic forces, and van der Waals forces. These forces can cause assay components to adhere unintentionally to surfaces, non-target proteins, or other interfering molecules, leading to elevated background noise, false positives, or false negatives. This guide provides targeted troubleshooting advice and detailed protocols to help you identify the sources of NSB in your experiments and implement effective strategies to minimize it, thereby enhancing the specificity and sensitivity of your assays.

FAQ: Understanding the Forces Behind Non-Specific Binding

1. What are the primary molecular forces responsible for non-specific binding?

The main culprits are hydrophobic interactions, electrostatic forces, and van der Waals forces [15]. Hydrophobic interactions drive the association of non-polar surfaces or molecules in an aqueous environment [16]. Electrostatic forces involve attractions between positively and negatively charged groups on molecules or surfaces [11] [5]. Van der Waals forces are weak, distance-dependent interactions arising from correlated fluctuations in the electron clouds of nearby atoms or molecules [17]. In many cases, NSB results from a combination of these forces rather than a single one.

2. How does non-specific binding impact diagnostic and research assays?

NSB can lead to false positives and false negatives, which directly compromise data integrity [1]. In immunodiagnostic assays, for example, this can result in the misdiagnosis of a disease or improper treatment decisions [1]. In drug discovery, ligands that self-assemble into colloidal aggregates can nonspecifically inhibit target proteins, leading to false positives in high-throughput screens [18].

3. Which types of molecules or compounds are most prone to causing NSB?

Large, amphipathic molecules often present the greatest challenge. This includes peptides, proteins, peptide-drug conjugates (PDCs), and nucleic acid drugs, which exhibit pronounced electrostatic and hydrophobic effects [11]. Cationic lipids, with their positively charged head groups and hydrophobic tails, are also particularly prone to adsorption [11]. Furthermore, some small molecule drugs in discovery can form sub-micrometer aggregates that inhibit enzymes nonspecifically [18].

4. Can the physical surfaces of my labware contribute to NSB?

Yes, the chemical nature of contact surfaces is a major factor. Glassware can engage in ion-exchange reactions, plastic consumables (like polypropylene and polystyrene) can interact via electrostatic and hydrophobic effects, and metal surfaces in liquid chromatography systems can also promote binding via electrostatic effects [11]. Using low-adsorption consumables designed for specific molecule types (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids) is a key mitigation strategy [11].

Troubleshooting Guide: Identifying and Resolving NSB

Problem: High Background or False Positives in Immunoassays (e.g., ELISA, Western Blot)

- Potential Cause 1: Incomplete Blocking. The blocking buffer may not be effectively preventing primary and secondary antibodies from binding to the membrane or other assay components [19].

- Solution: Increase the concentration of your blocking reagent (e.g., from 2% to 5% BSA), extend the blocking incubation time, or switch to an engineered blocking buffer [19] [20]. For fluorescent Western blotting, use a buffer specifically designed for that application [19].

- Potential Cause 2: Low Antibody Specificity or High Concentration. The primary antibody may have low specificity for your target, or the concentration used may be too high, promoting off-target binding [19] [20].

- Solution: Titrate your primary antibody to find the lowest effective concentration. Perform the primary antibody incubation at 4°C to reduce non-specific binding. For polyclonal antibodies, which are more promiscuous, consider switching to a monoclonal antibody if the problem persists [20].

- Potential Cause 3: Hydrophobic or Electrostatic Interactions. The antibody may be interacting with surfaces or non-target molecules via its Fc region or other domains [1].

- Solution: Use a commercial immunoassay diluent or blocker, such as those containing proprietary formulations of proteins and surfactants, which are designed to block Fc receptors and other sites of nonspecific interaction without sacrificing the intended assay signal [1].

Problem: Non-Specific Bands in Western Blot

- Potential Cause: Antibody Cross-Reactivity or Protein Multimers. The antibody might be recognizing similar epitopes on other proteins, or your target protein may form dimers/trimers [20].

- Solution: Check the literature to see if your protein is known to form multimers; if so, boiling the sample in Laemmli buffer for 5-10 minutes may disrupt them [20]. Ensure you are not overloading the gel with too much protein, as this can cause "ghost bands" [20]. Increase the number and stringency of washes (e.g., use 0.1% Tween-20) [20].

Problem: Loss of Signal or Irreproducible Results in Bioanalytical Assays (e.g., Sample Analysis for PK Studies)

- Potential Cause: Analyte Adsorption to Consumables. This is a common issue for peptides, proteins, PDCs, and nucleic acid drugs, especially in low-protein matrices like urine, bile, or cerebrospinal fluid [11].

- Solution: Add a carrier protein like BSA to compete for binding sites, use low-adsorption tubes and plates, or include a suitable surfactant in the solution to improve the solubility state of the analytes [11].

Problem: Non-Specific Signals in Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR)

- Potential Cause: Direct, non-specific interaction of the analyte with the sensor chip surface. This can be due to charge-based or hydrophobic interactions [5].

- Solution: Systematically optimize your running buffer. This can include:

- Adjusting buffer pH to neutralize the charge of your analyte or the sensor surface [5].

- Adding a non-ionic surfactant like Tween 20 (e.g., 0.05%) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [5].

- Increasing salt concentration (e.g., 150-200 mM NaCl) to shield electrostatic attractions [5].

- Using a protein blocker like BSA (e.g., 1%) to coat the surface [5].

Problem: Colloidal Aggregation in Drug Screening

- Potential Cause: Ligand self-association into large colloidal assemblies that nonspecifically inhibit target proteins [18].

- Solution: Include additives like the non-ionic detergent Triton X-100 (e.g., 0.01%) or human serum albumin (HSA) in your assay buffer. These attenuators can convert inhibitory aggregates into non-binding coaggregates or act as a competitive sink for the free inhibitor, respectively [18].

Experimental Protocols for Mitigating NSB

Protocol 1: Optimizing a Blocking Buffer for Immunoassays

This protocol is designed to reduce NSB in techniques like ELISA and Western blotting by combining multiple blocking mechanisms.

Materials:

- PBS Buffer

- Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA)

- Non-ionic surfactant (e.g., Tween-20)

- Normal IgG from the host species of your secondary antibody

- (Optional) Dextran Sulfate

Procedure:

- Prepare a base buffer of 1x PBS.

- Add BSA to a final concentration of 1-3% (w/v) as a primary blocking agent.

- Add Tween-20 to a final concentration of 0.05-0.1% (v/v) to disrupt hydrophobic interactions.

- Add normal IgG (e.g., 0.1 mg/mL) to bind to potential non-specific sites [21].

- For antibody-oligonucleotide conjugates, include 0.02-0.1% (w/v) dextran sulfate to compete for electrostatic binding and 150 mM NaCl to increase ionic strength [21].

- Mix the solution thoroughly and ensure the pH is appropriate for your assay (typically 7.2-7.4 for PBS).

- Use this buffer for blocking and, if compatible, for diluting your antibodies.

Protocol 2: Evaluating and Preventing Analyte Adsorption in Solution

Use this method to test if your valuable samples (e.g., proteins, peptides) are adsorbing to vial walls during storage or processing.

Materials:

- Your analyte in solution

- Low-adsorption microtubes (e.g., protein/low-bind tubes)

- Standard polypropylene microtubes

- Silanized glass vials (optional)

- Selected additives (e.g., BSA, CHAPS, Tween-20)

Procedure:

- Prepare a dilute solution of your analyte in your standard buffer.

- Aliquot equal volumes of this solution into both standard tubes and low-adsorption tubes.

- As a test, add a potential desorption agent (e.g., 0.1% BSA or 0.01% Tween-20) to another aliquot in a standard tube.

- Store all tubes for a set time (e.g., 1-2 hours) at the temperature you plan to use.

- Recover the solution and quantify the analyte concentration using a sensitive method (e.g., HPLC, spectrophotometry).

- Compare the recovery rates. A significantly higher recovery from the low-adsorption tube or the tube with additives indicates that NSB to the standard tube surface was occurring.

Quantitative Data for Assay Optimization

Table 1: Common Surfactants and Additives to Reduce NSB

| Additive | Type | Common Working Concentration | Primary Mechanism of Action |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSA | Protein Blocker | 1-5% (w/v) | Blocks adsorption sites on surfaces; shields the analyte from interactions [5]. |

| Tween 20 | Non-ionic Surfactant | 0.05-0.1% (v/v) | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions [5] [20]. |

| Triton X-100 | Non-ionic Surfactant | 0.01-0.1% (v/v) | Prevents hydrophobic compounds from aggregating; interferes with aggregate-protein interactions [18]. |

| NaCl | Salt | 150-200 mM | Shields electrostatic interactions by increasing ionic strength [5] [21]. |

| Dextran Sulfate | Polyanion | 0.02-0.1% (w/v) | Competes with negatively charged molecules (e.g., nucleic acids) for electrostatic binding sites [21]. |

| EDTA | Chelating Agent | 1-5 mM | Chelates metal ions, reducing metal-mediated adsorption on surfaces [11]. |

Table 2: Strategies for Different Biological Matrices

| Matrix Type | NSB Challenges | Recommended Desorption Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| Plasma/Serum | Complex matrix; weak adsorption due to carrier proteins. | Use commercial immunoassay diluents designed for complex samples [1]. |

| Urine, Bile, Cerebrospinal Fluid | Low protein/lipid content increases adsorption risk. | Add organic reagents, BSA, or surfactants; use low-adsorption consumables [11]. |

| Fecal Homogenates | Complex and heterogeneous. | Use surfactants; passivate solid surfaces [11]. |

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Key Reagents for Minimizing Non-Specific Binding

| Reagent | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| StabilGuard / StabilBlock | Commercial dried protein stabilizers and blockers that provide a one-step process for stabilizing coated proteins and blocking surfaces. | Immunoassay development on microplates and other solid surfaces [1]. |

| MatrixGuard Diluent | Commercial protein-containing assay diluent designed to block matrix interferences in complex biological samples while maintaining true assay signal. | IVD kit manufacturing; immunoassays using serum or plasma [1]. |

| Low-Adsorption Tubes/Plates | Consumables with specially treated surfaces that minimize the adsorption of biomolecules. | Sample storage and analysis for peptides, proteins, and nucleic acids [11]. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) | Polymer used in chemical surface modifications to create a hydrophilic, protein-repellent layer. | Functionalization of electrode surfaces in biosensors [15]. |

Visualization of NSB Mitigation Strategies

The following diagram illustrates a decision-making workflow for diagnosing and addressing the primary causes of non-specific binding.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: Why is there often a discrepancy between the binding affinity (Kd) I measure in a simple biochemical assay and the activity I see in a cellular assay?

This is a common challenge driven by the fundamental differences between a test tube and a cell. In a standard biochemical assay with a buffer like PBS, your protein interacts with its ligand in an idealized, dilute solution. Inside a cell, the environment is drastically different due to factors like macromolecular crowding, different ionic concentrations, viscosity, and lipophilicity. These intracellular physicochemical conditions can alter Kd values by up to 20-fold or more [22]. Additionally, in a cellular context, you must account for membrane permeability, target specificity, and compound stability, which do not influence purified biochemical assays [22].

FAQ 2: What are "quinary interactions" and how do they affect my assay results?

Quinary interactions are weak, non-specific interactions that occur between your protein of interest and the vast network of other macromolecules, membranes, and protein complexes inside a cell [23]. While these interactions may be transient, they can significantly slow down the tumbling rate of your protein, leading to broadened signals or even a complete loss of signal in techniques like NMR [23]. In a binding assay, this "stickiness" of the protein surface can lead to inaccurate measurements of binding affinity, as the theoretical model for a 1:1 interaction in a clean solution no longer holds [24] [23].

FAQ 3: My in-cell Western assay has a high background. Could the buffer environment be a factor?

While high background in an in-cell Western is often linked to antibody-specific issues like insufficient blocking or non-specific antibody binding [25], the crowded intracellular environment can exacerbate these problems. The complex matrix can increase the likelihood of non-specific binding. Furthermore, inadequate cell fixation and permeabilization—steps that are highly sensitive to buffer conditions like pH and salt concentration—can lead to incomplete antibody penetration and uneven staining, contributing to a high background signal [25].

Troubleshooting Guide: Bridging the Biochemical-Cellular Assay Gap

Problem: Inconsistent Kd values between biochemical and cellular binding assays.

Potential Causes and Solutions

| Potential Cause | Underlying Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Non-physiological Buffer | Standard buffers (e.g., PBS) mimic extracellular, not intracellular, conditions [22]. | Replace PBS with a cytoplasm-mimicking buffer (see "Experimental Protocol" section below). |

| Ligand Depletion | In cell-based assays, a significant fraction of the ligand binds to receptors, reducing the free ligand concentration and distorting Kd calculations [24]. | Ensure the receptor concentration is <0.1 x Kd. If not, use equations to correct for depletion in your data analysis [24]. |

| Failure to Reach Equilibrium | The binding reaction is measured before it has reached a steady state, leading to an inaccurate Kd [24]. | Calculate the equilibrium half-time (t1/2) and incubate the reaction for at least 5 x t1/2 to ensure >97% equilibrium [24]. |

| Macromolecular Crowding | The crowded cytoplasmic environment affects protein diffusion, conformational dynamics, and binding behavior [22] [23]. | Incorporate macromolecular crowding agents (e.g., Ficoll, dextrans) into your biochemical assay buffer [22]. |

Problem: Protein signals are lost or broadened in in-cell NMR experiments.

Potential Causes and Solutions

| Potential Cause | Underlying Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Specific Functional Interactions | The protein is engaging with its natural binding partners inside the cell, which slows its tumbling rate [23]. | This may be a desired biological outcome. To study the free protein, consider using a non-native cellular environment (e.g., express a human protein in bacterial cells) [23]. |

| Non-Specific "Sticky" Interactions | The protein surface interacts weakly with various cellular components, a phenomenon known as quinary structure [23]. | Introduce point mutations on the protein's surface to reduce its overall "stickiness" while preserving its fold, as demonstrated with Profilin 1 [23]. |

Experimental Protocol: Creating a Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer

Standard phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) is designed for extracellular conditions and is inadequate for simulating the intracellular environment. The table below compares key parameters, highlighting the significant gaps [22].

| Physicochemical Parameter | Standard PBS (Extracellular-like) | Cytoplasmic Environment | Cytoplasm-Mimicking Buffer Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dominant Cation | Na⺠(157 mM) | K⺠(140-150 mM) | Use K⺠as the dominant cation (e.g., 140-150 mM). |

| Potassium (Kâº) | Low (4.5 mM) | High (140-150 mM) | Drastically reduce Na⺠levels (to ~14 mM). |

| Macromolecular Crowding | No | Yes (20-40% of volume) | Add crowding agents (e.g., 100-200 g/L Ficoll-70 or similar polymers). |

| Viscosity | Low (~1 cP) | Higher (~3-4 cP) | Adjust viscosity with glycerol or other viscogens. |

| Redox Potential | Oxidizing | Reducing (high glutathione) | Use with caution: Consider low mM DTT or β-mercaptoethanol, but note they may disrupt disulfide bonds [22]. |

Detailed Protocol:

- Base Buffer: Start with a buffer that uses a potassium salt, such as Potassium Phosphate or HEPES-KOH, to maintain a pH of ~7.2-7.4.

- Ionic Composition: Add KCl to bring the potassium concentration to approximately 150 mM. Keep the total Na⺠concentration low (aim for ~14 mM).

- Crowding and Viscosity: Incorporate a macromolecular crowding agent like Ficoll-70 at a concentration of 100-150 g/L. This will simultaneously increase the viscosity and mimic the crowded cellular interior.

- Other Components: Add Mg²⺠(1-2 mM) as an essential cofactor for many biological processes. The use of reducing agents is system-dependent and should be empirically tested.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Cytoplasmic Mimicry

| Research Reagent | Function in Assay | Brief Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Ficoll-70 / Dextrans | Macromolecular Crowding Agent | Inert polymers that simulate the volume exclusion and altered diffusion effects of the crowded cellular cytoplasm, which can significantly influence binding equilibria and kinetics [22]. |

| HEPES-KOH Buffer | pH Buffering | A good buffering system that allows for the creation of a high Kâº, low Na⺠environment, mirroring the cytoplasmic ionic balance [22]. |

| Dithiothreitol (DTT) | Reducing Agent | Mimics the reducing environment of the cytosol (maintained by glutathione). Caution: Can denature proteins with structural disulfide bonds [22]. |

| AzureCyto In-Cell Western Kit | Standardized Cellular Assay | A commercial kit that provides validated reagents for assays like in-cell Westerns, reducing optimization time and improving consistency by mitigating issues like high background [25]. |

| GCPII-IN-1 | GCPII-IN-1, CAS:1025796-32-0, MF:C12H21N3O7, MW:319.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PDE4-IN-16 | PDE4-IN-16, CAS:223500-15-0, MF:C13H12F3N3O2, MW:299.25 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Diagram: The Assay Environment Gap Impact

The diagram below illustrates how different buffer environments influence experimental outcomes, leading to the gap between biochemical and cellular assay results.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is non-specific binding (NSB) and how does it affect my data? Non-specific binding (NSB) occurs when an antibody, ligand, or analyte binds to unintended sites, such as non-target proteins, assay container walls, or sensor surfaces, rather than specifically to its intended target [5] [1]. In PK assays, this can lead to false positives by creating a signal where no specific interaction exists, or false negatives by sequestering the analyte and reducing the detectable signal, thereby compromising data accuracy and leading to incorrect conclusions about a drug's concentration or behavior [18] [10] [1].

What are the common experimental hallmarks of NSB? Common signs that your experiment may be affected by NSB include:

- Promiscuous Inhibition: Your compound shows activity against multiple, unrelated target proteins [18].

- Bell-Shaped or Non-Classical Dose-Response Curves: Potency increases with concentration but then decreases at higher levels, which can indicate the ligand is being sequestered by aggregates or other sinks [18].

- Reduced Potency in the Presence of Additives: The apparent effect of your compound changes when non-ionic detergents (e.g., Triton X-100, Tween) or carrier proteins (e.g., BSA, HSA) are added to the assay [18] [5].

- Increased Potency with Prolonged Incubation Time: This can suggest slow formation of inhibitory aggregates [18].

- Inconsistent or Low Analytical Recovery: Especially in PK assays, this can indicate adsorption of your analyte to container walls or system tubing [10].

How can I confirm the presence of colloidal aggregates, a common cause of NSB? You can use direct and indirect methods to detect aggregating compounds [18]:

- Direct Observation: Techniques like Dynamic Light Scattering (DLS) and Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) can visually identify and size sub-micrometer colloidal aggregates.

- Indirect Confirmation: Saturation Transfer Difference (STD) NMR can signal the presence of high molecular weight complexes like aggregates. The appearance of STD signals at concentrations above the critical aggregation concentration (CAC) is indicative of self-association [18].

What are the main mechanisms by which NSB attenuators work? Different agents reduce NSB through distinct mechanisms, which is important for experimental design as they can also potentially suppress specific signals [18]:

- Non-Ionic Detergents (e.g., Triton X-100, Tween 20): Attenuate ABI by converting inhibitory, protein-binding aggregates into non-binding coaggregates [18]. They also disrupt hydrophobic interactions [5].

- Carrier Proteins (e.g., Bovine Serum Albumin - BSA, Human Serum Albumin - HSA): Minimize nonspecific interactions by acting as a reservoir for the free inhibitor, preventing its self-association into aggregates and its adsorption to surfaces [18] [5]. They can also shield the analyte from charged surfaces [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Mitigating NSB in Pharmacokinetic (PK) Assays

PK assays are particularly susceptible to NSB, which can derail critical decisions in drug development [10].

Problem: Inaccurate measurement of drug concentration due to analyte loss to container surfaces or system components, leading to low recovery and unreliable data [10].

Investigation and Solutions:

- Step 1: Identify the Binding Surface. Understand the properties of the surfaces your analyte contacts (e.g., glass, polypropylene, polystyrene, metal filters in HPLC systems) [10].

- Step 2: Match the Solution to the Problem. Based on the binding surface and your compound's properties, implement one or more of the following strategies:

| Problem Cause | Mitigation Strategy | Specific Action |

|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobic Interactions (e.g., with plastic surfaces) [10] | Use low-adsorption consumables; add mild detergents [10]. | Use polypropylene containers labeled "low-binding"; add non-ionic surfactants like Tween 20 to solutions (e.g., 0.01-0.1%) [10] [5]. |

| Charge-Based Interactions (e.g., with glass silanol groups) [10] | Adjust ionic strength; use charged competitors [10] [5]. | Increase the salt concentration (e.g., 150-200 mM NaCl) in your buffer to shield electrostatic attractions [5]. |

| General Adsorption | Add a carrier protein [10]. | Include Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) at 1-5% (w/v) in your buffers to act as a competitive scavenger for nonspecific sites [26] [5]. |

Advanced Consideration: For new molecular entities like peptides and oligonucleotides, NSB can occur on chromatographic columns, leading to peak tailing and carryover. Mitigation strategies include adjusting the mobile phase ionic strength, using inert tubing, and increasing column temperature [10].

Guide 2: Overcoming NSB in Biomolecular Binding Assays (e.g., SPR, NMR)

Binding assays like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) and NMR are powerful tools but are highly vulnerable to artifacts from NSB [18] [5].

Problem: Nonspecific interactions between the analyte and the sensor surface (SPR) or nonspecific protein-ligand associations (NMR) inflate response signals or cause misleading shifts, leading to erroneous affinity and kinetic calculations [18] [5].

Investigation and Solutions: A preliminary test is to run your analyte over a bare sensor surface (SPR) or look for specific vs. nonspecific spectral patterns (NMR). If NSB is detected, use the following table to select countermeasures:

| Strategy | Mechanism | Protocol Example |

|---|---|---|

| Optimize Buffer pH [5] | Adjusts the net charge of biomolecules to reduce electrostatic NSB. | Determine the isoelectric point (pI) of your protein. Set the buffer pH to a value where the protein has a neutral net charge, or away from the pI if surface charge is opposite [5]. |

| Add Non-Ionic Surfactant [18] [5] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions by forming non-binding coaggregates or micelles. | Add Triton X-100 to your running buffer at a low concentration (e.g., 0.01-0.05%). Note: This can also suppress specific binding, so use judiciously [18]. |

| Include a Blocking Protein [18] [5] | Competes for and saturates nonspecific binding sites on surfaces. | Use BSA or human serum albumin (HSA) at 1-5% (w/v) in your assay buffer. In SPR, this can also prevent analyte loss to tubing [5]. |

Key Experimental Insight: NMR studies have revealed that some aggregating ligands form a distinct class of aggregates that do not bind proteins but act as competitive sinks for the free inhibitor, causing a decrease in specific signal at high concentrations (bell-shaped curves). This dissociation can be observed in NH-HSQC titrations as chemical shifts revert toward the ligand-free state [18].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Properties of Aggregating Inhibitors

The following data, derived from investigations on EPAC-selective inhibitors, quantifies the characteristics of colloidal aggregation [18].

| Ligand | Critical Aggregation Concentration (CAC) | Average Aggregate Diameter (DLS) | Aggregate Morphology (TEM) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CE3F4R | ~150 µM | ~250 nm | Amorphous |

| ESI-09 | ~150 µM | ~250 nm | Spherical, Micellar |

Protocol 1: Differentiating Specific Binding from Aggregation-Based Inhibition (ABI) using NMR

This protocol outlines how to use NMR to distinguish specific ligand-protein interactions from nonspecific aggregation-based inhibition [18].

Objective: To map specific binding sites and identify the concentration at which nonspecific aggregation interferes.

Materials:

- Uniformly 15N-labeled target protein (e.g., EPAC1CBD)

- Ligand of interest (e.g., CE3F4R, ESI-09)

- NMR spectrometer

- Appropriate deuterated buffer

Method:

- Prepare Samples: Create a series of samples with a constant concentration of your 15N-labeled protein and increasing concentrations of the ligand, spanning below and above its suspected CAC.

- Acquire NH-HSQC Spectra: For each titration point, collect an NH-HSQC spectrum.

- Analyze Spectral Changes:

- Specific Binding: Look for residue-dependent, multidirectional chemical shift changes in the protein's cross-peaks at ligand concentrations below the CAC.

- Aggregation-Based Interference: At concentrations above the CAC, monitor for one of two phenomena:

- Severe Line Broadening: Indicates transient interaction with large, slow-tumbling aggregates.

- Reversion of Shifts: A shift of cross-peaks back toward the ligand-free state suggests the ligand is being sequestered by aggregates, dissociating from the protein [18].

- Control Experiment: Perform a parallel titration with a carrier solvent (e.g., DMSO) to account for nonspecific solvent effects.

Protocol 2: A Mathematical Method to Correct for NSB in Mass Spectrometry and Single-Molecule Studies

This method separates specific from nonspecific binding without assuming a cooperative binding mechanism [27].

Objective: To determine the true distribution of specific binding stoichiometries from data inflated by nonspecific binding.

Assumptions:

- The number of specific binding sites, Ns, is known.

- Nonspecific binding is non-cooperative and can be described by a single binding constant, Kn [27].

Method:

- Determine Kn: Calculate the nonspecific association constant from the ratio of intensities for peaks corresponding to binding numbers larger than Ns. For a protein with two specific sites, Kn can be found from I₄/I₃ = Kn[S], where [S] is the free ligand concentration [27].

- Calculate Corrected Populations: Use the derived Kn to calculate the corrected concentration of protein species, CN, with N ligands bound to specific sites, using the formula: CN/[E] = Σ [ ( (Kn[S])â±â»Â¹ * IN - (*K*n[*S*])â± * I(N-1) ) / Iâ‚€ ] where the summation is over the observed peaks, and [E] is the free protein concentration [27].

- Determine Specific Binding Constants: The specific binding constants (K1, K2, etc.) can be obtained from the relationship CN/[E] = KN[S] C(N-1)/[E] [27].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential reagents used to prevent and mitigate NSB in various experimental contexts.

| Reagent | Function & Mechanism | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Triton X-100 [18] | Non-ionic detergent that converts protein-binding inhibitory aggregates into non-binding coaggregates. | Attenuating aggregation-based inhibition (ABI) in enzymatic assays; reducing hydrophobic NSB. |

| Tween 20 [5] | Mild non-ionic surfactant that disrupts hydrophobic interactions. | Reducing NSB in SPR and immunoassays; preventing analyte adsorption to tubing and containers. |

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) [26] [5] | Carrier protein that blocks nonspecific sites on surfaces and acts as a reservoir for hydrophobic compounds. | Blocking in IHC, ELISA, and SPR; additive in assay buffers to improve solubility and recovery. |

| Human Serum Albumin (HSA) [18] | Physiological carrier protein that prevents ligand self-association by acting as a competitive sink. | Used in HTS to minimize false positives from NSB; more physiologically relevant than BSA for some studies. |

| Normal Serum [26] | Contains antibodies and proteins that bind to reactive sites, preventing nonspecific binding of secondary antibodies. | Blocking in IHC and other immunodetection applications. Must be from the secondary antibody host species. |

| Commercial Blockers (e.g., StabilGuard) [1] | Proprietary formulations designed to maximize signal-to-noise ratio by blocking matrix interferences. | Optimizing immunoassays (ELISA, bead-based assays) to reduce false positives and false negatives. |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-59 | 4-(4,5-Dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)benzonitrile|CAS 850786-33-3 | 4-(4,5-Dihydro-1H-imidazol-2-yl)benzonitrile (SARS-CoV-2-IN-59). High-purity compound for research applications. For Research Use Only. Not for human or veterinary use. |

| Licarbazepine-d4-1 | Licarbazepine-d4-1, CAS:1188265-49-7, MF:C15H14N2O2, MW:258.31 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Experimental Workflows and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates the cascading effects of non-specific binding on experimental data and decision-making, and the parallel pathway for mitigation.

Practical Strategies: Proven Techniques to Reduce NSB in Your Assays

FAQs and Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ: Core Principles of Buffer Optimization

1. How do pH and ionic strength fundamentally affect biomolecular interactions? pH and ionic strength are critical environmental factors that govern the charge properties of biomolecules like proteins and antibodies. The pH of a solution determines the net charge of a protein by influencing the ionization state of its amino acid side chains. Ionic strength, referring to the concentration of ions in a solution, affects the shielding of these charges. High ionic strength solutions screen electrostatic attractions and repulsions between molecules, which can reduce non-specific binding driven by charge [28] [29].

2. What is the relationship between ionic strength and the Debye length? The Debye length (λD) is the distance over which a single charge is electrically screened by the ionic atmosphere in a solution. It is inversely related to the square root of the ionic strength. As ionic strength increases, the Debye length decreases, meaning electrostatic forces are effective over much shorter distances. For instance, at a physiological ionic strength of ~150 mM, the Debye length is about 0.78 nm, whereas at a low ionic strength of 1.6 mM, it elongates to 7.7 nm [28]. This is crucial for biosensor design and understanding binding events.

3. When should I adjust pH versus ionic strength to reduce non-specific binding? The choice depends on the primary cause of non-specific binding (NSB). If NSB is caused by hydrophobic interactions, adjusting pH will have minimal effect, and strategies like adding mild detergents are more suitable. If NSB is primarily due to charge-based interactions, both parameters can be tuned. Adjusting the pH to the isoelectric point (pI) of the interfering molecule can neutralize its charge, while increasing the ionic strength can shield existing charges [28] [5].

Troubleshooting Guide: Common Buffer-Related Issues

Problem: High Background Signal in a Binding Assay (e.g., ELISA) A high background signal often indicates that non-specific binding is occurring.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Charge-based NSB | Increase the salt concentration (e.g., NaCl) in the assay and wash buffers to shield charge interactions. Start with an addition of 150-200 mM [5]. |

| Ineffective Blocking | Change your blocking reagent (e.g., switch from BSA to a casein-based blocker) or add a blocking agent to your wash buffer [30]. |

| Insufficient Washing | Ensure a rigorous washing protocol with adequate soak times (e.g., add 30-second soak steps) to remove loosely bound molecules [30]. |

| Wrong Buffer pH | Adjust the pH of your buffers to ensure your protein of interest is not charged opposite to the surface or other components [5]. |

Problem: Inconsistent Results Between Experimental Replicates Erratic data can stem from unstable or improperly prepared buffer conditions.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Buffer Evaporation | Always seal assay plates completely with a fresh sealer during all incubation steps to prevent evaporation and concentration changes [30]. |

| Inconsistent Buffer Temperature | Ensure all buffers and reagents are at room temperature before starting the assay to avoid temperature-induced pH drift [31] [30]. |

| Poor Pipetting Technique | Use calibrated pipettes and ensure all reagents are mixed thoroughly before use to guarantee homogeneity [30]. |

| Old or Contaminated Buffers | Prepare fresh buffer solutions for each experiment. Precipitates or microbial growth can alter buffer properties [30]. |

Problem: Low or No Specific Signal When the desired specific signal is weak or absent, buffer conditions may be interfering with the target interaction.

| Potential Cause | Solution |

|---|---|

| Salt Concentration Too High | While salt reduces NSB, excessively high ionic strength can also disrupt specific, charge-dependent interactions. Titrate the salt concentration to find an optimal level [5]. |

| Incompatible Buffer | Ensure the assay buffer is compatible with your target. Check for enzyme inhibitors (e.g., sodium azide inhibits HRP) [30]. |

| pH Too Far from Optimal | The binding affinity between some molecules can be insensitive to pH over a range, but for others, it may be critical. Check the literature for the optimal pH of your specific interaction [28]. |

The following tables consolidate experimental data on how pH and ionic strength affect biomolecular interactions.

Table 1: Impact of Ionic Strength on Binding Affinity

This data, derived from a study on C-reactive protein (CRP) and its antibody, shows how sensitive an interaction can be to the ionic strength of the environment [28].

| Ionic Strength (mM) | Debye Length (nm) | Relative Binding Affinity |

|---|---|---|

| 1.6 | 7.7 | 45% |

| 11.0 | 2.9 | Data Not Provided |

| 23.1 | 2.0 | Data Not Provided |

| 150.7 | 0.78 | 100% |

Table 2: Effect of pH on IgG Binding to a Weak Cation Exchanger

This data illustrates how pH, by altering the net charge of a protein, dictates its binding to a charged surface. The binding capacity is highest when the protein (IgG) is positively charged and the surface is negatively charged [29].

| pH | Membrane Zeta Potential | IgG Net Charge | Static Binding Capacity |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4.5 | +6.8 mV | Positive | High |

| 5.3 | 0 mV (Isoelectric point) | Neutral | Very Low / None |

| 7.0 | -40 mV | Negative | Very Low / None |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Systematic Optimization of Buffer pH and Ionic Strength

This protocol provides a methodology for empirically determining the optimal buffer conditions to maximize specific signal and minimize background.

1. Prepare Stock Solutions:

- 1 M Phosphate Buffer Stock: Prepare separate 1 M stocks of Naâ‚‚HPOâ‚„ and KHâ‚‚POâ‚„. Mixing these in varying ratios will allow you to create buffers with a pH range from approximately 5.9 to 8.1 [28].

- 4 M NaCl Stock: For adjusting ionic strength.

- Blocking Solution: 1% Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) in your base buffer.

- Wash Buffer: 0.05% Tween 20 in your base buffer.

2. Set Up a Multi-Well Plate:

- Immobilize your ligand (e.g., an antibody or antigen) onto a multi-well plate overnight at 4°C [28].

- Remove the solution, rinse the wells three times with Wash Buffer, and then incubate with Blocking Solution for 1 hour to prevent non-specific binding.

- Rinse the wells again to prepare for the assay.

3. Test Analyte Binding:

- Prepare a dilution series of your analyte (the binding partner) in buffers of different pH and ionic strength. A suggested starting range for ionic strength is 1.6 mM to 150 mM, and for pH, 5.9 to 8.1 [28].

- Incubate the analyte solutions in the prepared wells for 1 hour.

- Rinse the wells four times with Wash Buffer to remove unbound analyte.

4. Detect and Analyze:

- Depending on your assay, use an appropriate detection method (e.g., fluorescence, colorimetric substrate).

- Measure the signal for each condition. The optimal condition is the one that yields the highest specific signal with the lowest background.

Protocol 2: Evaluating and Reducing Non-Specific Binding (NSB) in SPR

This protocol outlines steps to diagnose and mitigate NSB in Surface Plasmon Resonance experiments.

1. Diagnose NSB:

- Before immobilizing your specific ligand, flow your analyte over a bare sensor chip or a chip coated with an irrelevant protein.

- A significant response in this control channel indicates a problem with NSB [5].

2. Optimize Running Buffer: If NSB is detected, systematically add the following components to your running buffer and sample diluent, testing the NSB after each addition:

- Add a Blocking Agent: Include 1% BSA to block hydrophobic surfaces and prevent loss of analyte to tubing and surfaces [5].

- Add a Non-ionic Surfactant: Include 0.05% Tween 20 to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [5].

- Adjust Ionic Strength: Add NaCl to shield charge-based interactions. A concentration of 200 mM is a good starting point [5].

3. Validate:

- After optimizing the buffer, the response in the NSB control channel should be minimal. You can then subtract any remaining NSB signal from your specific binding data during analysis [5].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent | Function in Buffer Optimization |

|---|---|

| BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) | A common blocking agent used to coat surfaces and prevent non-specific binding of proteins to plastics, glass, and sensor surfaces [5]. |

| Tween 20 | A non-ionic surfactant that disrupts hydrophobic interactions, a major cause of non-specific binding. It is typically used at low concentrations (e.g., 0.05%) [5]. |

| Sodium Chloride (NaCl) | Used to increase the ionic strength of a buffer. It shields charged groups on proteins and surfaces, thereby reducing charge-based non-specific binding [28] [5]. |

| Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) | A standard buffer system used in many biochemical assays due to its physiological pH and salt concentration. It serves as a common starting point for optimization [28]. |

| Sodium Phosphate Buffer | A customizable buffer system allowing researchers to adjust pH precisely over a relevant biological range (approximately pH 5.8 to 8.0) to study charge-dependent interactions [28]. |

| ABBV-4083 | ABBV-4083, CAS:1809266-03-2, MF:C53H82FNO17, MW:1024.2 g/mol |

| Methyl citrate | Methyl citrate, CAS:26163-61-1, MF:C7H10O7, MW:206.15 g/mol |

In immunological assays, the selection of an appropriate blocking buffer is a critical step for minimizing non-specific binding, a common source of background noise that can obscure true signals and lead to inaccurate data interpretation [32]. Blocking agents such as Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA), casein, non-fat dry milk, and various commercial formulations work by occupying the non-specific binding sites on surfaces like membranes, slides, or microtiter wells, thereby preventing non-specific antibody attachment [32]. A well-chosen blocking buffer enhances assay sensitivity and specificity by improving the signal-to-noise ratio, which is especially vital for detecting low-abundance proteins [32]. This guide provides a detailed overview of blocking agent selection, optimization, and troubleshooting, framed within the essential context of minimizing non-specific binding in biochemical assays research.

Blocking Buffer Selection Guide

Selecting the optimal blocking agent is system-dependent, as no single blocker is ideal for every application due to the unique characteristics of each antibody-antigen pair [33]. The choice often involves balancing sensitivity and background noise.

Comparison of Common Blocking Agents

The following table summarizes the properties, benefits, and considerations of commonly used blocking agents to aid in selection [32] [33].

| Blocking Agent | Composition | Best For | Advantages | Limitations & Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bovine Serum Albumin (BSA) | Purified single protein [33]. | - Biotin-streptavidin detection systems [32] [33].- Detecting phosphoproteins [33].- Assays requiring high sensitivity for low-abundance proteins [33]. | - Biotin-free (does not interfere with avidin-biotin systems) [33].- Does not contain phosphoproteins [33].- A single protein source reduces chances of cross-reaction [33]. | - Can be a weaker blocker, potentially leading to more non-specific binding [33].- Purity matters: Different BSA preparations can cause varying levels of non-specific binding; some may contain contaminants that assay reactants bind to [34]. |

| Casein | Purified milk protein [33]. | - Applications requiring very low background [32].- Biotin-avidin complexes [32]. | - Often provides lower background than non-fat milk or BSA [32].- Single-protein buffer reduces cross-reactivity risk [33].- Inert and biotin-free [33]. | - More expensive than non-fat milk [33].- Not recommended for assays using Alkaline Phosphatase (AP) labels with PBS buffer; use TBS instead [32]. |

| Non-Fat Dry Milk | A mixture of many proteins, including caseins and whey proteins [33]. | - General purpose, cost-effective blocking for many standard applications [32]. | - Inexpensive and widely available [33]. | - Contains biotin and phosphoproteins, which can interfere with streptavidin-biotin detection and phospho-protein detection [32] [33].- Multiple proteins can sometimes mask antigens or lower detection limits [33]. |

| Normal Sera (e.g., Goat, Rabbit) | Whole serum from various animals [32]. | - Immunoassays where the secondary antibody was produced in the same species as the normal serum (e.g., use Normal Goat Serum with a goat-derived primary antibody) [32]. | - Provides specific and effective blocking for assays involving serum components. | - Can be more expensive.- Requires matching the serum source to the experimental design. |

| Specialty Commercial Blockers (e.g., StartingBlock, Blocker FL, SuperBlock) | Various; often a single purified protein (casein, glycoprotein) or formulated mixtures [33]. | - Optimizing new systems or when traditional blockers fail [33].- Fluorescent Western blotting [32] [33].- Multiplex assays [32].- Situations requiring rapid blocking (<15 minutes) [33]. | - Often pre-optimized for performance and consistency.- Serum- and biotin-free formulations available [33].- Formulated to reduce fluorescent artifacts [33]. | - Generally more costly than homemade buffers.- Performance may vary; testing is recommended. |

| Fish Gelatin | Gelatin from fish sources [32]. | - Assays using antibodies of mammalian origin [32]. | - Less likely to cross-react with mammalian antibodies than BSA or milk [32]. | - Not recommended for AP antibody labels in PBS; use TBS or BBS buffers instead [32]. |

The following decision diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting the most appropriate blocking agent based on your assay requirements and potential interferences.

Experimental Protocols for Testing Blocking Efficiency

Empirically testing different blocking buffers is often necessary to achieve the best results for a specific assay system [33]. The following protocol provides a methodology for comparing blocking efficiency, particularly in ELISA formats.

Protocol: Comparing Blocking Buffer Performance in ELISA

This protocol is adapted from research highlighting the importance of testing different BSA preparations and other blocking agents to identify sources of non-specific binding [34].

1. Coating: Coat ELISA 96-well Maxisorp Immuno plates with 5 µg/ml of your target antigen (e.g., a complement protein) in PBS overnight at 4°C. Include control wells coated with 5 µg/ml of the blocking agent itself (e.g., BSA, casein) to assess non-specific binding of your reagents to the blocker [34]. 2. Washing: Wash the plate with a low-salt washing buffer (e.g., 10 mM Tris pH 7.2, 25 mM sodium chloride, 0.05% Tween 20, and 0.25% Nonidet-P40) [34]. 3. Blocking: Divide the plate and block different wells with different candidate buffers for 2 hours at 37°C. Tested buffers should include [34] [33]:

- PBS with 5% BSA (note the catalog number and purity)

- PBS with 5% Non-Fat Dry Milk

- PBS with 1-2% Casein

- A specialty commercial blocking buffer 4. Incubation with Primary Agent: Serially dilute your protein of interest (e.g., an antibody or viral protein) in a washing buffer containing a lower concentration (e.g., 1-4%) of the corresponding blocking agent. Add the dilutions to the plate and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour [34]. 5. Incubation with Detection Antibody: After extensive washes, add a specific detection antibody (e.g., rabbit anti-target antibody) diluted in washing buffer with blocking agent, and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour [34]. 6. Incubation with Enzyme Conjugate: After further washes, add a horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (e.g., donkey anti-rabbit IgG) and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour [34]. 7. Detection and Analysis: After final washes, incubate with a colorimetric substrate (e.g., TMB). Stop the reaction and measure the absorbance at 450 nm. A good blocking buffer will show a high specific signal in antigen-coated wells and a very low signal (comparable to background) in the blocker-coated control wells [34].

The workflow for this experimental protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Common Blocking and ELISA Problems

| Problem | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High Background | Insufficient blocking or washing [35]. | - Ensure fresh blocking buffer is used for an adequate time (30 min - 2 hrs) [32].- Increase wash number/duration. Invert plate to drain completely [35]. |

| Blocking agent cross-reacts with assay components [34]. | - Switch blocking agents (e.g., from milk to BSA for biotin systems, or to casein for lower background) [32] [33].- Use a specialty commercial blocker [33]. | |

| Weak or No Signal | Blocking agent is masking the antigen-antibody interaction [33]. | - Test a different, less obstructive blocker (e.g., switch from milk to BSA or a specialty protein) [33]. |

| Over-blocking, which can mask antigens or inhibit enzymes [33]. | - Reduce the concentration of the blocking agent.- Shorten the blocking incubation time. | |

| Inconsistent Results | Non-specific binding to contaminants in the blocking agent [34]. | - Use a higher purity grade of blocker (e.g., globulin-free, low-endotoxin BSA) [34].- Include controls coated only with the blocking agent to identify this issue [34]. |

| Inconsistent washing or temperature during steps [35]. | - Standardize washing protocols and ensure consistent incubation temperatures [35]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What is the main purpose of a blocking buffer? The primary purpose is to prevent non-specific binding of antibodies and other detection reagents to the assay surface (e.g., the microtiter well or membrane). This reduces background noise, increases the specificity of the signal, and improves the overall accuracy and reliability of the assay results [32].

How long should the blocking step be? The duration can vary depending on the assay and the blocking buffer, but it typically ranges from 30 minutes to 2 hours at room temperature or 37°C. The optimal blocking time should be determined empirically for each specific assay system [32].

Can the blocking buffer itself cause non-specific binding? Yes. Not all preparations of a blocking agent like BSA are alike. Some BSA lots may contain contaminants (e.g., globulins or endotoxins) that assay reactants can bind to, leading to false-positive signals. This highlights the need to use a consistent, high-purity product and to include appropriate controls (wells coated only with the blocker) to identify this problem [34].

Are there non-protein alternatives for blocking? Yes, alternatives include synthetic polymers and detergents such as polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) or Ficoll [32] [34]. These can be useful in cases where protein-based buffers might cross-react with the antibodies or antigens in the assay [32].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Blocker BSA (10% Solution) | A purified, single-protein blocking agent. | Ideal for phosphoprotein detection and biotin-streptavidin systems where milk cannot be used [32] [33]. |

| Blocker Casein | A purified casein solution in PBS. | Used when very low background is critical; a high-performance replacement for homemade milk buffers [33]. |

| StartingBlock Blocking Buffer | A ready-to-use, serum- and biotin-free single protein solution. | Excellent for optimizing new systems, stripping/reprobing blots, and general use with a wide range of antibodies [33]. |

| Blocker FL Fluorescent Blocking Buffer | A detergent-free, single-protein blocking buffer. | Specifically formulated for fluorescent Western blotting to reduce fluorescent artifacts and background [33]. |

| Normal Sera (Goat, Rabbit, etc.) | Serum containing a mix of proteins from a specific animal. | Provides specific blocking when the secondary antibody is derived from the same species [32]. |

| Fish Gelatin Concentrate | Gelatin from fish sources. | Ideal for blocking when using mammalian antibodies to avoid cross-reactivity [32]. |

| SARS-CoV-2-IN-43 | SARS-CoV-2-IN-43, CAS:4940-52-7, MF:C16H12O3, MW:252.26 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Sodium 3-Methyl-2-oxobutanoic acid-13C2 | Sodium 3-Methyl-2-oxobutanoic acid-13C2, CAS:634908-42-2, MF:C5H7NaO3, MW:140.08 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Core Mechanisms & FAQs

â–‹ How do surfactants like Tween 20 reduce non-specific binding in assays?

Non-specific binding (NSB) in biochemical assays often stems from hydrophobic interactions and other weak forces (e.g., hydrogen bonding, van der Waals forces) between assay components and solid surfaces like plastic wells or sensor chips [5]. Surfactants disrupt these interactions through their unique chemical structure.

Surfactant molecules contain a hydrophilic (water-loving) head and a hydrophobic (water-fearing) tail [36]. In solution, they form micelles that trap hydrophobic impurities [37]. More importantly, they adsorb to hydrophobic interfaces on the assay surface, creating a hydrophilic layer that prevents proteins and other molecules from sticking nonspecifically [5] [36]. As non-ionic surfactants, they perform this function without introducing charges that could interfere with electrostatic interactions in your assay [38] [39].

â–‹ What concentration of Tween 20 should I use?

The optimal concentration is typically low, between 0.05% to 0.1% (v/v) in standard wash and blocking buffers [38] [39] [36]. The table below summarizes standard concentrations for different applications.

Table 1: Standard Tween 20 Concentrations for Common Applications

| Application | Typical Tween 20 Concentration | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| ELISA/Western Blot Wash Buffers (PBS-T/TBS-T) | 0.05% - 0.1% [38] [40] [36] | Reduce background by washing away nonspecifically bound proteins [36]. |

| Blocking Buffers (with BSA or milk) | ~0.05% [36] | Enhance blocking efficiency by coating hydrophobic sites on the membrane/plate [36]. |

| Antibody Diluents | ~0.1% [36] | Stabilize antibodies and prevent their nonspecific adsorption to tube walls [5] [36]. |

| Membrane Protein Extraction | Up to 2% [36] | Gently remove peripheral membrane proteins without dissolving the lipid bilayer [38]. |

â–‹ When would I choose an ionic surfactant over a non-ionic one like Tween 20?

The choice depends on the primary cause of NSB and the stability of your biomolecules. Tween 20 is the preferred first choice for most immunoassays to disrupt hydrophobic interactions [5] [40]. Consider ionic surfactants only when NSB is driven by strong electrostatic interactions and your protein can tolerate the conditions.

Table 2: Surfactant Selection Guide Based on NSB Cause

| Type of Surfactant | Example | Mechanism to Reduce NSB | Best For / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Ionic | Tween 20 [38] [36] | Disrupts hydrophobic interactions; forms a hydrophilic barrier [5] [37]. | Most immunoassays (ELISA, Western Blot) [38] [39]. Gentle, non-denaturing [36]. |

| Anionic | SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) [37] | Disrupts hydrophobic & electrostatic interactions; can denature proteins. | Strongly charged surfaces; note it may destroy protein structure and activity [37]. |

| Cationic | CTAB (Cetyltrimethylammonium bromide) [37] | Disrupts hydrophobic & electrostatic interactions; can denature proteins. | Strongly charged surfaces; note it may destroy protein structure and activity [37]. |

| Protein Additive | BSA (Bovine Serum Albumin) [5] [41] | Physically blocks sites and shields the analyte via its varied charge domains [5]. | Often used in combination with 0.05-0.1% Tween 20 for a synergistic effect [5] [41]. |

Advanced Applications & Combinatorial Strategies

For challenging cases of NSB, particularly in sensitive biosensing techniques like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Biolayer Interferometry (BLI) where high analyte concentrations are used, a combinatorial blocking strategy is often necessary [5] [41].

â–‹ Advanced Buffer Formulations

Research indicates that common additives like BSA or Tween 20 alone may only marginally suppress NSB at high micromolar analyte concentrations [41]. A more effective approach uses an admixture of blockers. One study demonstrated that a combination of 1% BSA, 20 mM imidazole, and 0.6 M sucrose dramatically reduced NSB across a range of proteins in BLI [41]. In this formulation:

- BSA acts as a physical blocking protein.

- Sucrose, an osmolyte, enhances protein solvation and reduces aggregation.

- Imidazole helps block specific interactions with Ni-NTA biosensor tips.

- Tween 20 can still be incorporated at 0.005-0.01% for additional hydrophobic interaction disruption [41].

â–‹ Surfactant Effects on Binding Affinity

The impact of surfactants on specific binding can be complex. A systematic study on molecularly imprinted polymers showed that increasing surfactant concentrations generally decrease binding affinity for the target ligand [37]. This effect is most pronounced with ionic surfactants like SDS and CTAB, while the non-ionic Tween 20 has a much weaker depressive effect on specific binding, making it a safer choice for preserving the activity of your biomolecules of interest [37].

Troubleshooting Guide

â–‹ High Background Signal

- Problem: High, uniform background across the entire membrane or plate.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Insufficient Blocking: Increase blocking time and/or the concentration of your blocking agent (e.g., BSA, casein, non-fat dry milk) [40].

- Inadequate Washing: Increase the number and/or duration of washes between steps. Ensure your wash buffer contains 0.05-0.1% Tween 20 (e.g., PBS-T or TBS-T) [40] [36].

- Antibody Concentration Too High: Titrate your primary and/or secondary antibody to find the optimal dilution [40].

- Contamination: Prepare fresh buffers and use clean plasticware to avoid HRP contamination, which can turn over substrate [40].

â–‹ No or Weak Specific Signal

- Problem: The expected signal is absent or too weak, even though background is low.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Tween 20 Concentration Too High: While rare, very high concentrations of Tween 20 (>0.5%) can, in some cases, disrupt specific antibody-antigen interactions [42]. Re-optimize the Tween 20 concentration, especially in antibody incubation buffers.