Therapeutic Index: Calculation, Clinical Significance, and Application in Drug Development

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the therapeutic index (TI), a critical quantitative measure of drug safety.

Therapeutic Index: Calculation, Clinical Significance, and Application in Drug Development

Abstract

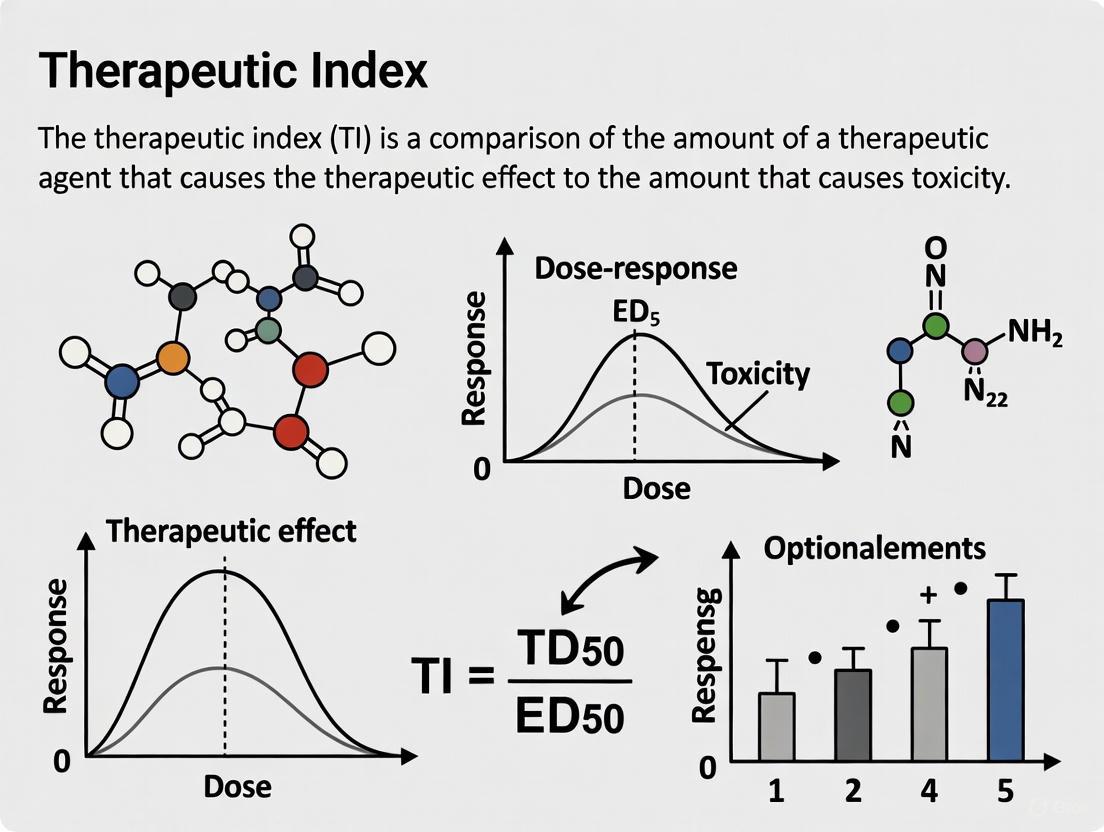

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the therapeutic index (TI), a critical quantitative measure of drug safety. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it covers the foundational principles of TI, including its standard calculation as TD50/ED50. It further explores methodological applications in preclinical and clinical settings, troubleshooting challenges with narrow-TI drugs, optimization strategies, and validation through regulatory and comparative frameworks. The content synthesizes current regulatory perspectives and scientific advancements to guide safety assessment throughout the drug development pipeline.

Defining the Therapeutic Index: Core Principles and Safety Significance

What is the Therapeutic Index?

The Therapeutic Index (TI) is a quantitative measurement of the relative safety of a drug, providing a critical comparison between its toxic dose and its therapeutic dose [1]. It is a cornerstone concept in pharmacology and drug development, serving as a key parameter for assessing the safety margin of a drug candidate [2]. In essence, the TI defines the window between the desired therapeutic effect and the onset of adverse effects, guiding dosing decisions in clinical practice and risk-benefit assessments during drug development [3] [4].

Core Concept and Calculation

The Therapeutic Index is fundamentally a ratio. Classically, it is calculated using the doses that produce a response in 50% of a population. In preclinical animal studies, the median lethal dose (LDâ‚…â‚€) is often used, while in clinical contexts, the median toxic dose (TDâ‚…â‚€) is more relevant [5] [1] [6].

The standard formulas are:

- Therapeutic Index (TI) = TDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€ or LDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€ [5] [7]

- Protective Index = TDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€ [1]

Where:

- EDâ‚…â‚€ (Median Effective Dose): The dose that produces a desired therapeutic effect in 50% of the test population [6].

- TDâ‚…â‚€ (Median Toxic Dose): The dose that produces a defined toxic effect in 50% of the population [6].

- LDâ‚…â‚€ (Median Lethal Dose): The dose that is lethal for 50% of the test population, primarily determined in animal studies [5] [6].

A higher TI value indicates a wider margin of safety. This means a patient would have to take a much higher dose to reach the toxic threshold than the dose required to elicit the therapeutic effect [7]. Conversely, a low TI indicates a narrow margin of safety, where the effective and toxic doses are close together [3] [4].

Table 1: Key Terms in Therapeutic Index Determination

| Term | Full Form | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| ED | Effective Dose | The dose or concentration of a drug that produces a intended biological response [1]. |

| EDâ‚…â‚€ | Median Effective Dose | The dose that produces a specified therapeutic effect in 50% of the population [6]. |

| TD | Toxic Dose | The dose at which toxicity occurs [1]. |

| TDâ‚…â‚€ | Median Toxic Dose | The dose required to produce a particular toxic effect in 50% of subjects [6]. |

| LDâ‚…â‚€ | Median Lethal Dose | The dose that causes death in 50% of a test population, typically measured in animal studies [5] [1]. |

Experimental Determination of Therapeutic Index

Determining the TI involves generating dose-response data for both efficacy and toxicity. The following workflow and methodology, exemplified by a comparative study of anti-inflammatory agents, outline a standard experimental approach [8].

Experimental Workflow for TI Determination

Detailed Methodology: In Vitro Assessment of Anti-inflammatory Agents [8]

This protocol determines the TI by comparing cytotoxicity (LCâ‚…â‚€) to the half-maximal inhibitory concentration (ICâ‚…â‚€) for a specific biochemical activity.

Cell Culture:

- Cell Line: Wehi-164 fibrosarcoma cells.

- Culture Conditions: Cells are maintained in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum, penicillin (100 U/mL), and streptomycin (100 µg/mL). Cultures are kept at 37°C in a humidified incubator with 5% CO₂.

Drug Treatment and Dose-Response:

- Test agents (e.g., dexamethasone, piroxicam, diclofenac, plant extracts like Glycyrrhiza glabra and Matricaria aurea) are prepared as sterile solutions.

- Two-fold serial dilutions of each agent are prepared in a phosphate-buffered saline (PBS).

- Triplicate wells of cells are treated with these dilutions for a set period (e.g., 24 hours). Untreated cells exposed only to PBS serve as the control.

Cytotoxicity Assay (Vital Dye Exclusion):

- After incubation, cells are washed with ice-cold PBS and fixed with 5% formaldehyde.

- Fixed cells are stained with a 1% crystal violet solution.

- After washing, the stained cells are lysed and solubilized with a 33.3% acetic acid solution.

- The density of the developed purple color is measured colorimetrically at 580 nm. The color density is directly proportional to the number of viable cells.

- Data Analysis: A concentration-response curve is plotted, and linear regression analysis is used to estimate the LCâ‚…â‚€ (the concentration that produces 50% cytotoxicity).

Functional Efficacy Assay (Gelatin Zymography):

- This step assesses the inhibition of matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), a therapeutically relevant target.

- Aliquots of conditioned media from treated cells are subjected to electrophoresis on gelatin-containing polyacrylamide gels (SDS-PAGE) under non-reducing conditions.

- Gels are then washed in 2.5% Triton X-100 to remove SDS and incubated for 24 hours at 37°C in an activation buffer (Tris-HCl, CaCl₂, pH 7.4).

- Gels are stained with Coomassie Blue. Proteolytic activity appears as clear bands against a blue background, where MMPs have digested the gelatin.

- Data Analysis: The surface and intensity of the lysis bands are quantified and compared to untreated controls. A concentration-response curve is plotted, and the ICâ‚…â‚€ (the concentration that produces 50% inhibition of MMP activity) is determined via linear regression.

Therapeutic Index Calculation:

- The TI for each agent is calculated using the formula: TI = LCâ‚…â‚€ / ICâ‚…â‚€ [8]. A higher TI indicates a more favorable safety profile for the anti-inflammatory effect.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for TI Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Wehi-164 Fibrosarcoma Cell Line | A model system to study the cytotoxic and anti-inflammatory (MMP inhibitory) effects of drugs in a controlled in vitro environment [8]. |

| RPMI-1640 Culture Medium | Provides essential nutrients and a stable environment to maintain cell viability and growth during the experiment [8]. |

| Test Agents (e.g., Diclofenac, Dexamethasone) | The investigational drugs or compounds whose safety and efficacy margins are being determined [8]. |

| Crystal Violet Stain | A vital dye used to distinguish and quantify viable cells after fixed treatment; it binds to cellular proteins and DNA [8]. |

| Gelatin-Embedded Polyacrylamide Gels | The substrate for zymography; gelatin serves as the target for MMP enzymes, allowing visual quantification of their inhibitory activity [8]. |

| SDS (Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate) | A detergent used in electrophoresis to denature proteins while maintaining their enzymatic activity after renaturation [8]. |

Interpretation and Clinical Relevance in Drug Development

The calculated TI is not just a number; its interpretation is critical for decision-making in drug development and clinical use. A key application is the classification of Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs.

Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) Drugs

NTI drugs are those where small differences in dose or blood concentration can lead to serious therapeutic failures or severe, life-threatening adverse reactions [4]. Regulatory bodies like the FDA characterize NTI drugs as having less than a 2-fold difference in the minimum toxic concentration (MTC) and minimum effective concentration (MEC) in the blood [4].

Table 3: Examples of Drugs and Their Therapeutic Indices

| Drug | Therapeutic Index (Approximate) | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Remifentanil [1] [7] | 33,000 : 1 | Very wide margin of safety; dosing is more forgiving. |

| Diazepam [1] [7] | 100 : 1 | Relatively wide safety margin. |

| Morphine [1] [7] | 70 : 1 | Moderate safety margin. |

| Warfarin [3] [4] | Narrow (approx. 2:1 or less) | Requires careful therapeutic drug monitoring (INR checks) and dose titration due to high risk of bleeding or thrombosis [3] [4]. |

| Digoxin [1] | ~2 : 1 | Narrow margin; small dose increases can lead to toxicity (arrhythmias). Requires blood level monitoring. |

| Lithium [3] [1] | Narrow | Blood levels must be monitored closely to avoid toxicity. |

Considerations and Limitations of the Therapeutic Index

While invaluable, the TI has limitations that scientists and clinicians must consider [5] [6]:

- Endpoint Dependency: The TI value for a single drug can vary dramatically depending on the chosen therapeutic and toxic endpoints.

- Inter-individual Variability: The TI is a population-based metric and does not account for idiosyncratic reactions or individual patient factors like genetics (pharmacogenomics), age, or drug interactions [5] [4].

- Slope of Dose-Response Curves: The classic TI calculation does not consider the slopes of the efficacy and toxicity curves. Two drugs can have the same TI, but one may become lethal over a very narrow dose range, while the other may have a more gradual transition [6].

- Exposure vs. Dose: In modern drug development, the TI is increasingly based on plasma exposure levels (AUC, Cmax) rather than administered dose, as this provides a more accurate reflection of the drug's presence at the target site [2] [1].

The following diagram summarizes the logical relationship between the dose, population response, and the derived TI, while also highlighting key influencing factors.

TI Determination and Influencing Factors

The Therapeutic Index remains a fundamental, quantitative tool for evaluating the safety profile of a drug. From initial in vitro screening to clinical application, the TI and its derivative concept—the narrow therapeutic index—provide an essential framework for ensuring that medications are both effective and safe. For researchers and drug developers, a deep understanding of its calculation, interpretation, and limitations is crucial for optimizing candidate selection and designing clinical trials. For clinicians, it underscores the importance of precise dosing and vigilant monitoring, especially for NTI drugs, to achieve optimal patient outcomes.

In preclinical and clinical pharmacology, the quantal dose-response relationship is fundamental for evaluating the efficacy and safety of a drug. Unlike a graded response, which measures the intensity of an effect in a single individual, a quantal response is a binary, "all-or-none" event where the specified effect is either observed or not in each member of a population [9] [10]. This model is essential for determining critical safety parameters, primarily the therapeutic index, which quantifies the relative safety of a drug.

The following table summarizes the core definitions of the key metrics derived from quantal dose-response curves:

| Term | Definition | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| ED50 | The dose of a drug that produces a specified therapeutic effect in 50% of the test population [6] [11]. | A measure of the median effectiveness; a lower ED50 indicates a more potent drug. |

| TD50 | The dose required to produce a particular toxic effect in 50% of the population [6] [1]. | A measure of the median toxicity. |

| LD50 | The dose required to cause death in 50% of a test population (typically determined in animal studies) [6] [1]. | A measure of lethality, used predominantly in preclinical drug development. |

These values are graphically determined from a quantal dose-response curve, which plots the cumulative percentage of a population responding as a function of the logarithm of the dose. This characteristically produces a sigmoidal (S-shaped) curve for each endpoint—effect, toxicity, and lethality [6] [10].

Experimental Determination and Protocols

Standardized Experimental Workflow

The determination of ED50, TD50, and LD50 follows a structured experimental protocol, typically conducted during the preclinical phase of drug development. The general workflow for establishing a quantal dose-response relationship can be visualized below.

Detailed Methodologies for Key Experiments

Protocol for ED50Determination

The objective is to determine the dose at which 50% of the test population exhibits a predefined therapeutic effect.

- Endpoint Definition: The quantal effect must be unambiguously defined. For an anticonvulsant drug, for instance, the endpoint could be "prevention of tonic hindlimb extension in an electroshock seizure model" [12].

- Population and Grouping: A homogeneous animal population (e.g., inbred strain of mice) is selected. Animals are randomly assigned to groups, with each group (typically 8-12 animals) receiving a different dose of the test drug. A control group receives the vehicle.

- Dosing and Measurement: Doses are administered, often spaced logarithmically (e.g., 1, 2, 4, 8 mg/kg). After a predetermined time, the stimulus (e.g., electroshock) is applied, and each animal is scored as either "protected" or "not protected."

- Data Analysis: The cumulative percentage of responders at each dose is plotted against the log-dose. The resulting sigmoidal curve is fitted using statistical methods like probit analysis, which linearizes the curve for more accurate estimation of the ED50 and its confidence intervals [12].

Protocol for TD50and LD50Determination

The methodology for TD50 is analogous to that for ED50, but the monitored endpoint is a specific adverse event (e.g., a predefined level of motor inc coordination or hepatotoxicity) [6]. The LD50 test, historically a cornerstone of toxicology, follows a similar protocol with mortality as the endpoint [6].

- Endpoint Definition: For LD50, the endpoint is unequivocally death within a specified observation period (e.g., 14 days). For TD50, the toxic effect (e.g., a 50% increase in serum creatinine indicating nephrotoxicity) must be objectively measurable.

- Dosing and Observation: Groups of animals receive progressively higher doses of the drug. Subjects are closely monitored for signs of toxicity and mortality for a set duration.

- Data Analysis: The cumulative percentage of animals exhibiting toxicity or death at each dose is plotted. The TD50 or LD50 is the dose corresponding to the 50% response on the fitted sigmoidal curve.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details essential materials and their functions in these experiments.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| Inbred Animal Model (e.g., C57BL/6 mice, Sprague-Dawley rats) | Provides a genetically homogeneous test population to reduce variability in dose-response data [6]. |

| Test Compound / Drug Candidate | The investigational substance whose efficacy and toxicity are being quantified. |

| Vehicle Solution (e.g., saline, DMSO, carboxymethylcellulose) | The solvent or carrier used to dissolve or suspend the test compound for administration; serves as the negative control. |

| Probit Analysis Software (e.g., specialized bioassay tools in SAS, R, or GraphPad Prism) | Statistical software used to linearize the sigmoidal quantal response data and accurately calculate median doses (ED50, LD50) and confidence intervals [12]. |

| Clinical Chemistry Analyzer | An automated instrument used to measure biomarkers in serum/plasma (e.g., ALT, Creatinine) to objectively define toxic endpoints (TD50) [6]. |

| UFP-512 | UFP-512, MF:C31H33N5O5, MW:555.6 g/mol |

| APX-115 free base | APX-115 free base, CAS:1270084-92-8, MF:C17H17N3O, MW:279.34 g/mol |

Calculation of the Therapeutic Index and Its Application

Therapeutic Index Formulae and Interpretation

The therapeutic index (TI), also known as the therapeutic ratio, is a quantitative measure of a drug's safety margin. It is calculated directly from the median doses obtained from quantal dose-response curves [6] [1] [5].

The most common formula used in clinical pharmacology is: TI = TD50 / ED50

A higher TI value indicates a wider margin of safety, meaning there is a large difference between the dose required for efficacy and the dose that causes toxicity. Conversely, a low TI indicates a narrow therapeutic window, requiring careful dose titration and monitoring [3] [13] [11].

In preclinical animal studies, the TI is often calculated using the lethal dose: TI = LD50 / ED50 [1]

Another related metric is the Protective Index (PI), which is identical to the clinical TI formula: PI = TD50 / ED50 [1]

The relationship between these curves and indices is critical for understanding drug safety. The following diagram illustrates how the ED50, TD50, and the resulting therapeutic window are derived from quantal curves.

Limitations and Modern Interpretations

While foundational, the classical therapeutic index has significant limitations that researchers must consider [6] [5]:

- Endpoint Dependency: Different therapeutic or toxic endpoints will yield different ED50 and TD50 values, meaning a single drug has multiple TIs.

- Idiosyncratic Toxicity: The TI does not account for unpredictable, non-dose-related adverse reactions (e.g., anaphylaxis).

- Curve Slope Ignorance: The TI is a ratio of two specific points and does not consider the slopes of the dose-response curves. Two drugs can have the same TI, but one may become toxic with a small dose increase if its toxicity curve is steep [6].

- Animal-to-Human Translation: Preclinical LD50 data from animals may not accurately predict human toxicity.

Due to these limitations, modern drug development increasingly relies on exposure-based therapeutic indices, which use plasma concentration (e.g., AUC or Cmax) at steady-state rather than administered dose, providing a more pharmacologically relevant safety margin [1].

Quantitative Data and Clinical Relevance

Comparative Therapeutic Indices of Common Drugs

The therapeutic index varies dramatically among drugs, directly influencing their clinical use and monitoring requirements. The table below provides representative examples.

| Drug | Therapeutic Index (Representative) | Clinical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Penicillin G | Very High [13] | Generally safe; wide margin between antibacterial and toxic doses. |

| Diazepam | ~100 : 1 [1] | Relatively safe, but overdose is possible. |

| Morphine | ~70 : 1 [1] | Requires careful dosing due to respiratory depression risk. |

| Warfarin | ~2 : 1 [1] [11] | Narrow Therapeutic Index; necessitates intensive monitoring (INR tests). |

| Lithium | ~2 : 1 [3] [1] | Narrow Therapeutic Index; requires regular serum level monitoring. |

| Digoxin | ~2 : 1 [1] | Narrow Therapeutic Index; small dose increases can lead to severe toxicity. |

Application in Drug Development and Regulation

The determination of ED50, TD50, and the resulting TI is integral to the drug development pipeline. Regulatory agencies like the FDA use this information to categorize drugs. Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs are subject to more stringent bioequivalence standards for generic approval and require specific clinical monitoring guidelines in their prescribing information [3] [11]. For NTI drugs, the inter-individual variability in pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics is a critical concern, driving the need for personalized dosing strategies and therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) to ensure patient safety while maintaining efficacy [1].

The therapeutic index (TI), also referred to as the therapeutic ratio, is a quantitative measurement of the relative safety of a drug. It is a critical parameter in pharmacology that compares the amount of a therapeutic agent that causes a toxic effect to the amount that elicits the desired therapeutic effect [1]. This ratio provides a fundamental safety margin estimate, guiding clinicians in dosing decisions and informing drug developers about a compound's risk-benefit profile [5]. The TI is foundational to both clinical practice and pharmaceutical development, serving as a key indicator for determining how safely a drug can be administered across diverse patient populations.

The related concepts of therapeutic window or safety window refer to the range of doses between the minimum concentration required for efficacy and the maximum concentration before unacceptable toxicity occurs. This window represents the dose range that optimizes therapeutic benefit while minimizing adverse effects, providing a crucial framework for dosage regimen design [1]. Understanding both the TI and therapeutic window is essential for maximizing patient safety, particularly for medications where the difference between effective and toxic concentrations is small.

Calculation Methods and Formulas

Core Calculation Formulas

The therapeutic index is classically calculated using median effective and toxic doses derived from quantal dose-response curves:

Standard Therapeutic Index:

TI = TDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€where TDâ‚…â‚€ represents the dose that produces a toxic effect in 50% of the population, and EDâ‚…â‚€ represents the dose that produces the desired therapeutic effect in 50% of the population [1] [5] [14].Preclinical Safety Assessment: In animal studies, the TI is often calculated as

TI = LDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€where LDâ‚…â‚€ is the lethal dose for 50% of the animal population [1] [15].Efficacy-based Therapeutic Index: An alternative calculation

TI = EDâ‚…â‚€ / TDâ‚…â‚€is sometimes used, where a lower value indicates a larger therapeutic window [1].

Advanced Safety Calculations

For more refined safety assessments, particularly for drugs with narrow TIs, additional calculations are employed:

Protective Index:

PI = TDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€which is the inverse of the efficacy-based therapeutic index [1].Certainty Safety Factor (CSF):

CSF = TD₠/ ED₉₉which represents the ratio between the dose toxic to 1% of the population and the dose effective for 99% of the population. A CSF > 1 indicates that the dose effective in 99% of patients is lower than the dose that would be toxic to 1% of patients [14].Standard Safety Margin:

[(TD₠- ED₉₉) / ED₉₉] × 100which expresses the percentage by which the ED₉₉ must be increased to reach the TD₠[14].

Figure 1: Hierarchy of Therapeutic Index Calculations and Related Safety Metrics

Experimental Protocols for TI Determination

Preclinical TI Assessment Protocol

Objective: To determine the median lethal dose (LDâ‚…â‚€) and median effective dose (EDâ‚…â‚€) in animal models during early drug development.

Methodology:

- Animal Models: Utilize at least two mammalian species (typically rodent and non-rodent) with both sexes represented

- Dosing Groups: Minimum of four dose levels with 8-10 animals per group

- Administration: Route matching intended clinical application (oral, intravenous, etc.)

- Observation Period: 14 days with continuous monitoring for mortality and toxic signs

- Data Collection: Record time of onset, duration, and severity of toxic effects

- Necropsy: Gross pathological examination of all animals

- Statistical Analysis: Probit analysis to calculate LDâ‚…â‚€ with 95% confidence intervals

Endpoint Measurements: Mortality rates, clinical observations, body weight changes, and gross pathology findings [1].

Clinical TI Assessment Protocol

Objective: To establish the therapeutic index in human subjects during clinical trials.

Methodology:

- Study Design: Randomized, double-blind, dose-ranging studies

- Patient Population: Representative of target indication with appropriate inclusion/exclusion criteria

- Dose Escalation: Multiple dose levels from subtherapeutic to dose-limiting toxicity

- Endpoint Assessment:

- Efficacy endpoints specific to indication

- Toxicity grading using standardized criteria (e.g., CTCAE)

- Pharmacokinetic Sampling: Intensive sampling to determine exposure-response relationships

- Statistical Analysis:

- Logistic regression for quantal dose-response curves

- Estimation of EDâ‚…â‚€ and TDâ‚…â‚€ with confidence intervals

- Population modeling to assess covariates affecting TI

Endpoint Measurements: Primary efficacy outcomes, adverse event incidence and severity, pharmacokinetic parameters (AUC, Cmax, Tmax) [15].

Interpretation of High vs. Low Therapeutic Index

Drugs with High Therapeutic Index

A high therapeutic index indicates a wide margin of safety, meaning there is a substantial difference between the dose required for therapeutic effects and the dose that causes toxicity. Drugs with high TI values (generally >10) are considered relatively safe, as patients would need to take a much higher dose than the therapeutic dose to reach the toxic threshold [1] [3]. These medications typically have a wide therapeutic window, allowing for flexible dosing with minimal risk of adverse events at standard therapeutic doses [16].

Examples of high TI drugs include:

For high TI drugs, therapeutic drug monitoring is generally not required, and they can often be administered without extensive dose individualization or frequent safety monitoring [3].

Drugs with Low Therapeutic Index

A low therapeutic index indicates a narrow margin of safety, with only a small difference between therapeutic and toxic doses. Drugs with low TI values (generally <3) are considered potentially dangerous, as small increases in dose can result in toxic effects [15] [16]. These medications have a narrow therapeutic window, requiring careful titration and close monitoring to maintain plasma concentrations within the therapeutic range while avoiding toxicity [14].

The US Food and Drug Administration defines a drug as having a narrow therapeutic index when there is less than a twofold difference in median lethal dose (LDâ‚…â‚€) and median effective dose (EDâ‚…â‚€), or when there is less than a twofold difference in minimum toxic concentrations (MTC) and minimum effective concentrations (MEC) in the blood [15].

Examples of low TI drugs include:

- Digoxin: TI ≈ 2:1 [1] [17]

- Lithium: Narrow therapeutic range [1] [14]

- Warfarin: Narrow therapeutic range [17] [14]

- Phenytoin: Narrow therapeutic range [14]

- Gentamicin: Narrow therapeutic range [14]

- Theophylline: Narrow therapeutic range [3]

Figure 2: Clinical Implications of High vs. Low Therapeutic Index Drugs

Quantitative Comparison of Drug Safety Profiles

Table 1: Therapeutic Indices of Common Medications

| Drug | Therapeutic Index | Therapeutic Class | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remifentanil | 33,000:1 [1] [7] | Opioid analgesic | Extremely wide safety margin; minimal overdose risk at therapeutic doses |

| Penicillin | >100 [17] [16] | Antibiotic | Wide safety margin; dosing flexible with minimal monitoring |

| Diazepam | 100:1 [1] [7] | Benzodiazepine | Moderately wide safety margin; some monitoring advised |

| Morphine | 70:1 [1] [7] | Opioid analgesic | Requires careful dosing due to respiratory depression risk |

| Cocaine | 15:1 [1] | Stimulant, local anesthetic | Narrow safety margin; high abuse and toxicity potential |

| Ethanol | 10:1 [1] | Sedative | Narrow safety margin; precise dosing control difficult |

| Paracetamol/Acetaminophen | 10:1 [1] | Analgesic/antipyretic | Narrow safety margin; hepatotoxicity with slight overdose |

| Digoxin | 2:1 [1] [17] | Cardiac glycoside | Very narrow safety margin; requires therapeutic drug monitoring |

Table 2: Drugs with Narrow Therapeutic Index Requiring Clinical Monitoring

| Drug | Primary Indication | Therapeutic Range | Toxic Manifestations | Monitoring Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Warfarin [14] [3] | Anticoagulation | INR 2.0-3.0 (most indications) | Bleeding, hemorrhage | INR, bleeding signs |

| Lithium [1] [14] | Bipolar disorder | 0.6-1.2 mEq/L | Tremor, polyuria, confusion, seizures | Serum lithium levels, renal function |

| Digoxin [1] [17] | Heart failure, atrial fibrillation | 0.5-2.0 ng/mL | Nausea, vomiting, arrhythmias, vision changes | Serum digoxin levels, ECG, electrolytes |

| Phenytoin [14] | Seizure disorders | 10-20 mg/L | Nystagmus, ataxia, drowsiness | Serum levels, neurological exam |

| Gentamicin [14] [3] | Severe bacterial infections | Peak: 5-10 mg/L (depending on infection)Trough: <1-2 mg/L | Nephrotoxicity, ototoxicity | Peak/trough levels, renal function, hearing tests |

| Theophylline [3] | Asthma, COPD | 10-20 mg/L | Nausea, tachycardia, seizures | Serum levels, clinical response |

Regulatory and Drug Development Considerations

Bioequivalence Standards for Narrow TI Drugs

For generic versions of narrow therapeutic index drugs, regulatory authorities generally recommend reduced bioequivalence limits due to the potential clinical consequences of small differences in bioavailability [15]. The standard bioequivalence acceptance range of 80-125% for the ratio of geometric means of AUC and Cmax may be tightened for NTIDs to ensure that generic substitutions do not result in toxic or subtherapeutic responses [15].

The high interpatient variability in drug exposure presents particular challenges for NTIDs. Highly variable drugs are defined by the FDA as those for which inter-subject variance (%CV) in exposure is greater than 30%. For some CAR-T cell therapies, pharmacokinetic variance can span three orders of magnitude, creating significant challenges for dosing precision [18].

Therapeutic Index in Advanced Therapeutics

The concept of therapeutic index applies differently to novel therapeutic modalities:

Engineered T-cell Therapies: These "living drugs" present unique challenges for TI determination due to their complex pharmacology involving proliferation, differentiation, tissue trafficking, and immune system interactions [18]. For CAR-T cells, both AUC and Cmax are predictive of both response and toxicity (primarily cytokine release syndrome), with some products showing little to no therapeutic index as the same mechanisms underlying efficacy also mediate toxicity [18].

Radiotherapy: The therapeutic ratio in cancer radiotherapy is determined by the maximum radiation dose for killing cancer cells and the minimum radiation dose causing acute or late morbidity in normal tissues. Strategies to improve the therapeutic ratio include employing image-guided intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IG-IMRT), protons, heavy ions, and molecular targeting of DNA repair pathways [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Methodologies

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Methods for TI Determination

| Reagent/Method | Function in TI Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| In Vivo Animal Models | Determination of LDâ‚…â‚€ and EDâ‚…â‚€ | Preclinical safety assessment in at least two mammalian species |

| Cell-Based Cytotoxicity Assays | In vitro assessment of therapeutic and toxic concentrations | High-throughput screening during early drug discovery |

| Liquid Chromatography-Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Precise quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices | Pharmacokinetic studies and therapeutic drug monitoring |

| Population PK/PD Modeling Software | Quantitative analysis of exposure-response relationships | Clinical trial data analysis and dose regimen optimization |

| Flow Cytometry | Cellular kinetics analysis for cell-based therapies | CAR-T cell persistence and activation monitoring |

| Cytokine Detection Assays | Quantification of inflammatory mediators | CRS risk assessment for immunotherapies |

| Genomic Sequencing Platforms | Identification of pharmacogenetic variants affecting drug metabolism | Personalized dosing strategies for NTIDs |

| Bioanalytical Method Validation Kits | Ensuring accuracy, precision, and reproducibility of concentration measurements | GLP-complinical preclinical and clinical studies |

| BSJ-03-123 | BSJ-03-123, MF:C47H56N10O11, MW:937.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Dabinol | Dabinol, CAS:41993-79-7, MF:C23H22O8, MW:426.4 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The therapeutic index remains a fundamental concept in pharmacology and drug development, providing a critical quantitative framework for assessing drug safety. The distinction between high and low TI drugs has profound implications for clinical practice, regulatory standards, and patient safety. Drugs with a narrow therapeutic index require sophisticated management strategies including therapeutic drug monitoring, careful dose titration, and consideration of individual patient factors that may influence drug disposition and response.

As drug development advances into novel modalities like engineered cell therapies, the traditional concepts of therapeutic index are being adapted to address increasingly complex pharmacological relationships. Nevertheless, the fundamental principle remains unchanged: optimizing the balance between efficacy and toxicity is paramount to developing and utilizing safe, effective therapeutics. Future directions in TI research will likely focus on personalized approaches that account for genetic, environmental, and disease-specific factors to maximize therapeutic benefit while minimizing risk for all patients.

The therapeutic index (TI) is a quantitative measurement of the relative safety of a drug, providing a critical assessment of the benefit-to-risk ratio for clinical use [1]. It is a comparison of the amount of a therapeutic agent that causes toxicity to the amount that causes the desired therapeutic effect [1]. Classically, the TI is calculated as the ratio of the dose that produces a toxic effect in 50% of the population (TDâ‚…â‚€) to the dose that produces an effective response in 50% of the population (EDâ‚…â‚€), expressed as TI = TDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€ [5]. In early preclinical animal studies, the lethal dose for 50% of the population (LDâ‚…â‚€) is sometimes used in place of the TDâ‚…â‚€ [1] [5].

The therapeutic window, sometimes called the safety window, refers to the range of plasma drug concentrations or doses between the minimum level required to achieve a clinical efficacy (the minimum effective concentration) and the maximum level at which unacceptable side-effects or toxicity begin to manifest [19] [1]. This window represents the target concentration range for optimizing individual dosage regimens, aiming for the greatest therapeutic benefit without resulting in unacceptable adverse effects [1]. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic range, there is little difference between toxic and therapeutic doses, making dosage adjustment critical and often guided by therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) protocols [1] [20].

Table 1: Key Terms in Therapeutic Index and Window Analysis

| Term | Abbreviation | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Effective Dose | EDâ‚…â‚€ | The dose that produces a therapeutic or biological response in 50% of the population [1]. |

| Toxic Dose | TDâ‚…â‚€ | The dose at which toxicity occurs in 50% of the population [1]. |

| Lethal Dose | LDâ‚…â‚€ | The dose at which death occurs in 50% of the population (measured in animal studies) [1]. |

| Therapeutic Index | TI | A quantitative measure of a drug's relative safety, calculated as TDâ‚…â‚€/EDâ‚…â‚€ or LDâ‚…â‚€/EDâ‚…â‚€ [1] [5]. |

| Therapeutic Window | - | The range of plasma drug concentrations between the minimum effective concentration and the maximum tolerated concentration [19] [1]. |

| Protective Index | PI | An alternative safety measure calculated as TDâ‚…â‚€/EDâ‚…â‚€, which is the inverse of the efficacy-based therapeutic index [1]. |

Quantitative Calculations and Interpretations

Types of Therapeutic Indices

The calculation and interpretation of the therapeutic index can be approached from two primary perspectives, safety and efficacy, leading to two distinct types of indices [1]:

- Safety-Based Therapeutic Index (TIsafety): This is calculated as TIsafety = LDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€ [1]. A higher value for this index is preferable, as it indicates that a much larger dose is required to reach the lethal threshold compared to the dose needed for the therapeutic effect, implying a wider safety margin [1].

- Efficacy-Based Therapeutic Index (TIefficacy): This is calculated as TIefficacy = EDâ‚…â‚€ / TDâ‚…â‚€ [1]. Conversely, a lower value for this index is preferable. This indicates that the dose required to produce a toxic effect is much higher than the dose required for efficacy, again signifying a larger therapeutic window [1].

The Protective Index (PI = TDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€) is mathematically the inverse of the TIefficacy and is often a more practical measure of safety, as it uses the toxic dose rather than the lethal dose, which is more relevant for many clinical adverse effects [1].

Interpreting Therapeutic Indices in Practice

A high TI value (from the safety perspective) indicates a wide margin of safety, meaning the drug can be administered at doses well above the EDâ‚…â‚€ without significant risk of lethal toxicity [1]. A low TI indicates a narrow margin of safety, where the effective and toxic doses are close together, necessitating careful dose individualization and monitoring [1].

Table 2: Representative Therapeutic Indices of Various Substances

| Drug / Substance | Therapeutic Index (Approximate) | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Remifentanil | 33,000:1 [1] | Very wide safety margin; considered very forgiving. |

| Diazepam | 100:1 [1] | Less forgiving safety margin than remifentanil. |

| Morphine | 70:1 [1] | Requires careful dosing due to moderate safety margin. |

| Cocaine | 15:1 [1] | Low safety margin; high risk of toxicity. |

| Ethanol | 10:1 [1] | Narrow safety margin; risk of acute poisoning. |

| Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) | 10:1 [1] | Narrow safety margin; overdose can cause severe hepatotoxicity. |

| Digoxin | 2:1 [1] | Very narrow therapeutic range; requires therapeutic drug monitoring. |

Methodologies: Relating Blood Concentration to Clinical Effect

Experimental Protocol for Determining Dose-Response

The following methodology outlines the key steps for establishing the dose-response and toxicity relationships necessary for calculating the therapeutic index in a preclinical setting.

- Objective: To determine the EDâ‚…â‚€ and TDâ‚…â‚€ (or LDâ‚…â‚€) of a novel drug candidate in an animal model to calculate its therapeutic index and establish an initial therapeutic window.

- Materials:

- Test Compound: The drug substance of interest, purified and solubilized in an appropriate vehicle.

- Animal Model: Typically rodents (e.g., Sprague-Dawley rats, CD-1 mice) of a defined strain, age, and weight range. Animals are randomly assigned to groups.

- Dosing Equipment: Calibrated syringes, gavage needles for oral administration, or micro-infusion pumps for intravenous delivery.

- Efficacy Assay Kit: Specific reagents and equipment to quantitatively measure the pharmacological response (e.g., ELISA kits for biomarker analysis, mechanical/thermal pain stimulus tools for analgesics).

- Clinical Pathology Analyzer: Automated hematology and clinical chemistry analyzer to assess biomarkers of organ toxicity (e.g., ALT, AST, creatinine, BUN).

- Procedure:

- Study Design: A minimum of five dose groups and a vehicle control group are established (n=10-20 animals per group). Doses are selected based on preliminary range-finding studies to bracket the anticipated effective and toxic doses.

- Dosing: The test compound is administered according to a predefined schedule (e.g., single dose, once-daily for 7 days) via the intended clinical route (oral, intravenous, etc.).

- Efficacy Assessment (for EDâ‚…â‚€): At a predetermined time post-dose (Tₘâ‚â‚“), the pharmacological effect is quantitatively measured for each animal. For example, in an analgesic study, the percentage reduction in pain response relative to controls is calculated.

- Toxicity Assessment (for TDâ‚…â‚€/LDâ‚…â‚€): Animals are monitored for signs of overt toxicity, morbidity, or mortality for a defined period (e.g., 14 days). Body weight, food consumption, and clinical observations are recorded daily. At the end of the observation period, blood samples are collected for clinical chemistry, and key organs are harvested for histopathological examination.

- Data Analysis: The quantitative efficacy data and the incidence of a predefined toxic event (or death) are recorded for each dose group. The EDâ‚…â‚€ and TDâ‚…â‚€/LDâ‚…â‚€ values are calculated using non-linear regression analysis (Probit analysis or log-dose vs. response curve fitting) using statistical software (e.g., GraphPad Prism, SAS).

- Calculation: The therapeutic index is calculated as TI = TDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€ (or LDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€).

Clinical Protocol for Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM)

In clinical practice, the relationship between blood concentration and effect is managed through TDM, which is the clinical practice of measuring specific drugs at designated intervals to maintain a constant concentration in a patient's bloodstream [20].

- Objective: To individualize the dosage regimen of a drug with a narrow therapeutic window to optimize clinical efficacy and minimize the risk of adverse effects.

- Indications for TDM: TDM is used for drugs with a narrow therapeutic range, marked pharmacokinetic variability, medications for which target concentrations are difficult to monitor, and drugs known to cause therapeutic and adverse effects [20]. It is particularly critical for drugs like digoxin, lithium, aminoglycosides, cyclosporine, and phenytoin [1] [20].

- Procedure:

- Initial Dosing: An initial dosage regimen is determined based on the patient's clinical condition, age, weight, organ function (especially hepatic and renal), and concomitant drug therapy [20].

- Blood Sampling: A blood sample (plasma or serum) is drawn at a precise time, typically at steady-state (after 4-5 half-lives of the drug) and at the correct time point in relation to the dosing interval (e.g., trough concentration just before the next dose) [20].

- Sample Analysis: The drug concentration in the blood sample is measured using validated analytical techniques, most commonly immunoassays or chromatographic methods like High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) coupled with mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) for high specificity and sensitivity.

- Interpretation and Dosage Adjustment: The measured concentration is compared to the established therapeutic range. A clinical pharmacist or pharmacologist uses pharmacokinetic principles to interpret the level in the context of the sampling time, dosage history, and patient's clinical response. The dosage regimen is then adjusted accordingly to bring and maintain the drug concentration within the target therapeutic window [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Successful research and clinical monitoring in this field rely on specific reagents and analytical tools. The following table details key materials used in the experiments and practices described.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Therapeutic Index and TDM Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function and Application in Research |

|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | The gold-standard analytical instrument for quantifying drug concentrations in biological matrices (e.g., plasma) with high specificity and sensitivity, essential for TDM and pharmacokinetic studies [20]. |

| Validated Drug Assay Kits | Ready-to-use immunoassay kits (e.g., ELISA) for specific drugs like digoxin or cyclosporine; provide a high-throughput, though sometimes less specific, alternative to chromatography for routine TDM [20]. |

| Pharmacokinetic Modeling Software | Software tools (e.g., WinNonlin, NONMEM) used to model concentration-time data, calculate key parameters (half-life, clearance), and simulate dosage regimens to predict and optimize drug exposure. |

| Clinical Chemistry & Hematology Analyzers | Automated systems to measure biomarkers of organ function and toxicity (e.g., liver enzymes, renal function markers) in preclinical and clinical studies, critical for defining the toxic dose (TDâ‚…â‚€) [20]. |

| Reference Standard (Drug Substance) | A highly purified and well-characterized sample of the drug, essential for calibrating analytical instruments and ensuring the accuracy and precision of concentration measurements. |

| Blank Biological Matrix | Drug-free plasma or serum from the relevant species, used to prepare calibration standards and quality control samples for bioanalytical method development and validation. |

| 1-Hexanol-d13 | 1-Hexanol-d13, MF:C14H9Br3N2O2, MW:476.94 g/mol |

| MS402 | MS402, MF:C20H19ClN2O3, MW:370.8 g/mol |

Critical Considerations and Diagram of Drug Fate and Effect

In modern drug development, the therapeutic index is increasingly calculated based on plasma exposure levels (e.g., Area Under the Curve - AUC) rather than administered dose, as it is the tissue exposure to the drug over time that drives both pharmacological and toxicological effects [1]. This accounts for inter-individual variability in drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion. For toxicities that manifest after multiple doses, the TI should be calculated using exposure at steady-state [1].

Historical Context and Evolution of TI in Pharmacology

The therapeutic index (TI) is a cornerstone concept in pharmacology, providing a quantitative measure of a drug's safety and relative efficacy. This whitepaper traces the historical context and evolution of TI from its origins in preclinical animal models to its current application in modern, exposure-based drug development. We detail the fundamental calculation methodologies, explore the critical distinction between safety-based and efficacy-based indices, and examine the regulatory and clinical challenges posed by narrow therapeutic index drugs. Framed within broader research on TI's role in pharmacotherapy, this guide serves as a technical resource for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, integrating quantitative data, experimental protocols, and visualizations to elucidate this pivotal pharmacological principle.

Core Concepts and Calculation

The therapeutic index (TI), also referred to as the therapeutic ratio, is a quantitative measurement of the relative safety of a drug [1]. It is a comparison of the amount of a therapeutic agent that causes toxicity to the amount that causes the desired therapeutic effect [1]. The primary purpose of the TI is to provide a comparative safety margin, helping clinicians and researchers understand the dose range in which a drug is effective without causing unacceptable adverse events [3].

The related concept of the therapeutic window (or safety window) describes the range of doses optimized between efficacy and toxicity, aiming to achieve the greatest therapeutic benefit without resulting in unacceptable side-effects [1]. In clinical practice, this window is often defined by the range of drug concentrations in the blood between the minimum effective concentration (MEC) and the minimum toxic concentration (MTC) [21].

Fundamental Calculations

Classically, the TI is calculated using median doses obtained from population dose-response curves.

- Standard Therapeutic Index (TI): The ratio of the dose that produces a toxic response in 50% of the population (TD50) to the dose that produces a therapeutic response in 50% of the population (ED50) [5] [4].

- Formula: TI = TD50 / ED50

- Lethal Dose Alternative: In preclinical animal studies, the TI may be calculated using the lethal dose for 50% of the population (LD50) [1] [15].

- Formula: TIsafety = LD50 / ED50

- Efficacy-based Therapeutic Index (TIefficacy): This formulation compares the effective dose to the toxic dose [1].

- Formula: TIefficacy = ED50 / TD50

- A lower TIefficacy indicates a larger therapeutic window.

- Protective Index (PI): Similar to the safety-based TI, it uses TD50 and ED50 [1].

- Formula: PI = TD50 / ED50

- It is the inverse of TIefficacy (PI = 1 / TIefficacy).

Interpreting the Therapeutic Index

The numerical value of the TI has direct implications for drug safety and clinical use.

- High TI: A drug with a high TI (e.g., 100 or 1000) has a wide margin of safety [1] [21]. There is a large difference between the dose required for efficacy and the dose that causes toxicity. This generally indicates a safer drug, where small dosage variations are unlikely to cause harm. Examples include penicillin and diazepam [1] [3].

- Low/Narrow TI: A drug with a low or narrow TI (e.g., less than 2-3) has a small safety margin [15] [4]. There is only a small difference between therapeutic and toxic doses. For these drugs, small increases in dose can result in toxic effects, while small decreases can lead to therapeutic failure. Examples include warfarin, digoxin, and lithium [1] [3] [4]. Drugs with a narrow TI are also known as narrow therapeutic index drugs (NTIDs) or critical dose drugs [15].

Historical Evolution and Modern Approaches

The concept and application of the therapeutic index have evolved significantly from its origins in basic toxicology to a more nuanced, exposure-driven parameter in contemporary drug development.

Historical Preclinical Foundation

The earliest determinations of TI were frequently performed in animals and utilized mortality as the primary toxicity endpoint [1]. The LD50 (median lethal dose) was a standard metric, and the TI was calculated as LD50 / ED50 [1] [15]. This "academic" definition was straightforward for preclinical experiments but opened the door to variable interpretations in clinical practice, where severe toxicities often occur at sublethal doses [1] [15].

Shift to Clinical and Exposure-Based Paradigms

Modern pharmacology has moved away from reliance on lethal doses toward more sophisticated and clinically relevant endpoints.

- From Dose to Exposure: A critical advancement has been the recognition that it is the exposure of a given tissue to a drug (i.e., drug concentration over time), rather than the administered dose, that drives both pharmacological and toxicological effects [1]. Factors such as inter-individual variability in metabolism, drug-drug interactions (DDIs), body weight, and environmental factors can lead to marked differences in exposure at the same dose [1].

- Plasma Exposure Levels: In modern drug development settings, TI is typically calculated based on plasma exposure levels, such as the maximum plasma concentration (Cmax) and the area under the plasma concentration-time curve (AUC) [1] [15]. This allows for a more accurate and personalized assessment of the benefit-risk profile.

- Steady-State Considerations: To account for delays between exposure and toxicity, the TI for toxicities that occur after multiple dose administrations should be calculated using exposure to the drug at steady state rather than after a single dose [1].

Regulatory Definitions and Refinements

Regulatory bodies have refined the definition of NTIDs to guide clinical practice and generic drug approval. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has proposed that a drug product can be considered an NTID if it meets criteria such as [15] [4]:

- There is less than a twofold difference in median LD50 and ED50 values, or in minimum toxic (MTC) and minimum effective concentrations (MEC).

- Safe and effective use requires careful titration and patient monitoring.

- Small differences in dose or concentration lead to serious therapeutic failures and/or adverse drug reactions that are life-threatening.

This evolution in thinking underscores that TI is not just a static number but a dynamic parameter whose interpretation must consider the nature of the pharmacological and toxicological endpoints [1].

Quantitative Data and Drug Examples

The therapeutic index varies widely among pharmaceutical substances, even within related therapeutic classes. The table below summarizes the TI for a range of drugs, illustrating the spectrum from very safe to those requiring extreme caution.

Table 1: Therapeutic Indices of Selected Drugs

| Drug | Therapeutic Index (Approximate) | Clinical Context and Monitoring |

|---|---|---|

| Remifentanil [1] | 33,000 : 1 | An opioid with an exceptionally high TI, indicating a very wide margin of safety. |

| Diazepam [1] | 100 : 1 | A benzodiazepine with a relatively high TI, but still requires careful dosing. |

| Morphine [1] | 70 : 1 | An opioid analgesic; dosage must be individualized to balance pain control and respiratory depression. |

| Penicillin [3] | High (Wide TI) | Considered a very safe drug; toxic doses are much higher than effective doses. |

| Cocaine [1] | 15 : 1 | A stimulant and local anesthetic with a low safety margin. |

| Ethanol [1] | 10 : 1 | A sedative with a narrow TI; toxic effects can occur at doses not much higher than those causing intoxication. |

| Paracetamol/Acetaminophen [1] | 10 : 1 | Common analgesic; overdose can cause severe liver damage. |

| Digoxin [1] | 2 : 1 | A cardiac glycoside with a very narrow TI; requires therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). |

| Warfarin [3] [4] | Narrow TI | An anticoagulant where small dosage changes can lead to thrombosis or hemorrhage; requires frequent INR monitoring. |

| Lithium [1] [3] | Narrow TI | Used for psychiatric disorders; requires TDM due to its narrow therapeutic range. |

| Theophylline [1] [3] | Narrow TI | A bronchodilator; TDM is used to maintain levels within the therapeutic window. |

| Gentamicin [1] [3] | Narrow TI | An antibiotic; TDM is essential to ensure efficacy and avoid nephro- and ototoxicity. |

Methodologies and Protocols

Determining the therapeutic index involves a series of structured preclinical and clinical experiments. The following protocols outline the core methodologies for establishing key parameters.

Preclinical Protocol: Determining ED50 and LD50/TD50

Objective: To quantitatively determine the median effective dose (ED50) and median toxic/lethal dose (TD50/LD50) for a novel chemical entity in an animal model of disease.

Workflow:

- Animal Model Selection: Select a species and strain appropriate for the disease target (e.g., rodent model of epilepsy for an anticonvulsant drug).

- Dose Formulation: Prepare the test article in a vehicle suitable for the chosen route of administration (e.g., oral gavage, intravenous injection).

- Dose-Ranging Study: Conduct an initial dose-ranging study to identify the approximate range of doses that cause no effect, the desired therapeutic effect, and toxicity/mortality.

- Definitive Dose-Response Study:

- Groups: Randomly assign animals to 5-8 dose groups, plus a vehicle control group (n=10-20 per group).

- Dosing: Administer a single dose of the test article or vehicle to each group.

- Therapeutic Effect Measurement (for ED50): At a predetermined time post-dose, apply a standardized stimulus or measurement to quantify the drug's effect (e.g., measure pain threshold in an analgesic model). Record the proportion of animals in each group showing a positive therapeutic response.

- Toxicity/Mortality Observation (for TD50/LD50): Observe animals for a defined period (e.g., 24-72 hours) for signs of severe toxicity or mortality. Record the proportion of animals in each group showing the toxic endpoint.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot the dose versus the percentage of animals responding (for both effect and toxicity) on a logarithmic scale.

- Fit the data points with a sigmoidal curve (e.g., using log-probit analysis or non-linear regression).

- ED50 Calculation: From the efficacy dose-response curve, determine the dose that produces the therapeutic effect in 50% of the animals.

- TD50/LD50 Calculation: From the toxicity dose-response curve, determine the dose that produces toxicity or death in 50% of the animals.

- TI Calculation: Calculate the preclinical TI as TD50 / ED50 or LD50 / ED50.

Clinical Protocol: Bioequivalence Study for Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Objective: To demonstrate that a generic drug product is bioequivalent to a reference (brand-name) NTI drug, ensuring that switching between products does not lead to therapeutic failure or toxicity.

Workflow:

- Study Design: A full-replicate, crossover design is recommended by regulatory agencies like the FDA [4]. In this design, the same subject receives both the reference product (R) and the test product (T) twice, in a randomized sequence (e.g., TRTR, RTRT).

- Subject Selection: Enroll healthy volunteers or patients (as appropriate) who meet strict inclusion/exclusion criteria.

- Dosing and Sampling: After an overnight fast, subjects receive a single dose of the assigned product. Blood samples are collected at predetermined intervals over multiple half-lives to characterize the plasma concentration-time profile.

- Bioanalytical Analysis: Measure the concentration of the active drug in all plasma samples using a validated method (e.g., LC-MS/MS).

- Pharmacokinetic Analysis: Calculate key PK parameters for each subject and period:

- AUC(0-t): Area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to the last measurable time point.

- AUC(0-∞): Area under the plasma concentration-time curve from zero to infinity.

- Cmax: Maximum observed plasma concentration.

- Statistical Analysis for Bioequivalence (BE): For NTI drugs, the FDA employs a reference-scaled average bioequivalence approach with tightened limits [4].

- The 90% confidence interval (CI) for the ratio of the geometric means (Test/Reference) for AUC and Cmax must fall within a narrowed range, typically 90.00% - 111.11% (when within-subject variability is low), instead of the standard 80.00% - 125.00% [4].

- Additionally, the within-subject variability of the test product must not be significantly greater than that of the reference product.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Therapeutic Index Research

| Reagent / Material | Function in TI Research |

|---|---|

| In Vivo Disease Models (e.g., transgenic mice, induced-pathology models) | Provides a biological system to evaluate the therapeutic effect (ED50) of a compound in a physiologically relevant context. |

| Test Article/Investigational Drug | The compound whose safety and efficacy are being quantified; must be of high and defined purity. |

| Vehicle for Formulation (e.g., saline, carboxymethyl cellulose, DMSO) | A physiologically compatible solvent or suspension agent to deliver the test article to the animal. |

| Analytical Standards (Pure drug substance, metabolites) | Essential for developing and validating bioanalytical methods (e.g., LC-MS/MS) to accurately measure drug concentrations in plasma and tissues for exposure-based TI calculations. |

| Cell-Based Assays for Cytotoxicity (e.g., MTT, LDH assays) | Used for initial, high-throughput screening of compound toxicity (TD50) in vitro before proceeding to more complex animal studies. |

| Validated Pharmacodynamic (PD) Biomarker Assay (e.g., ELISA, enzymatic activity assay) | A tool to quantitatively measure the drug's biological effect in both preclinical and clinical settings, helping to define the therapeutic response. |

| GNE-140 racemate | GNE-140 racemate, MF:C25H23ClN2O3S2, MW:499.0 g/mol |

| Hck-IN-1 | Hck-IN-1, MF:C16H11ClN6O3S, MW:402.8 g/mol |

Regulatory and Clinical Implications

The therapeutic index, particularly its narrow manifestation, has profound implications for drug regulation and clinical practice.

Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs (NTIDs) in Clinical Practice

Drugs with a narrow TI present unique clinical challenges. Their use requires careful individualization of dosage, as small changes in dose or blood concentration can lead to serious therapeutic failure or severe adverse events [15]. For example, with warfarin, an INR below 2 increases the risk of thrombosis, while an INR above 3 increases the risk of hemorrhage [4].

Consequently, the standard of care for most NTIDs involves therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM). TDM involves regularly measuring drug concentrations in a patient's blood to ensure they remain within the therapeutic window [1] [3]. This is critical for drugs like lithium, gentamicin, and digoxin [1] [3]. Furthermore, patient factors such as age, comorbidities, and genetic polymorphisms (e.g., in CYP2C9 and VKORC1 for warfarin) can significantly impact dose requirements and must be considered [15] [4].

Regulatory and Bioequivalence Considerations

The concept of NTI is crucial in the regulatory approval of generic drugs. For most drugs, a generic product is considered bioequivalent if the 90% CI for the ratio of its AUC and Cmax to the reference product falls within 80-125% [15]. However, for NTIDs, this standard is considered too wide.

Regulatory authorities like the FDA and EMA recommend more stringent bioequivalence criteria for NTIDs to minimize the risk of patients being switched to a product that could be subtherapeutic or toxic [15] [4]. As detailed in the experimental protocol section, this often involves tightened BE limits (90-111%) and the use of reference-scaled average bioequivalence studies with a full-replicate design to closely compare the variability of the test and reference products [4]. This ensures that generic versions of NTIDs are virtually identical in their rate and extent of absorption to their brand-name counterparts.

Calculating and Applying the Therapeutic Index in Research and Development

The Therapeutic Index (TI) is a fundamental quantitative measurement in pharmacology used to evaluate the relative safety of a drug. It is a ratio that compares the dose of a drug required to elicit a toxic effect to the dose needed to produce the desired therapeutic effect [5] [1]. This comparison provides a crucial margin of safety, indicating how selective a drug is in producing its intended effect versus causing adverse reactions [6].

The classical formula for calculating the therapeutic index is: TI = TD~50~ / ED~50~ Where:

- TD~50~ (Median Toxic Dose) is the dose that produces a toxic effect in 50% of the population.

- ED~50~ (Median Effective Dose) is the dose that produces a therapeutic effect in 50% of the population [5] [1] [22].

In pre-clinical animal studies, the LD~50~ (Median Lethal Dose), or the dose that is lethal in 50% of the test population, is sometimes used in place of the TD~50~ [6] [15]. The TI is a cornerstone concept in both drug development and clinical practice, guiding dosage decisions and informing regulatory standards for drug approval [15] [4].

Core Components of the Calculation

The Median Effective Dose (ED~50~)

The ED~50~ is defined as the dose at which 50% of individuals exhibit a specified quantal, or "all-or-none," therapeutic effect [6] [11]. This parameter is derived from a quantal dose-response curve, which plots the percentage of a population responding against the drug dose [6]. The ED~50~ is a measure of a drug's potency; a lower ED~50~ indicates a more potent drug [11]. In clinical practice, the ED~50~ serves as a critical starting point for clinicians when determining initial drug doses, though adjustments are almost always necessary based on individual patient factors [11].

The Median Toxic Dose (TD~50~) and Lethal Dose (LD~50~)

The TD~50~ is the dose required to produce a particular toxic effect in 50% of subjects [6]. This mirrors the ED~50~ but uses a defined adverse event as the endpoint. In pre-clinical animal studies, toxicity is often taken to its extreme, leading to the use of the LD~50~, which is the dose that causes death in 50% of the test population [6]. The LD~50~ was first introduced by J.W. Trevan in 1927 as a more reliable metric than the highly variable "minimal lethal dose" [6]. It is crucial to note that the nature of the toxic effect (e.g., minor side effect vs. lethality) dramatically influences the calculated TI and its interpretation.

Deriving the Index from Dose-Response Curves

The ED~50~, TD~50~, and LD~50~ are all determined experimentally from cumulative quantal dose-response curves [6]. In an ideal scenario, the dose-response curves for efficacy and toxicity are parallel and widely separated. The TI is calculated by reading the respective doses from these curves and applying the standard formula [6] [14]. The following diagram illustrates the relationship between these curves and the derived values.

Experimental Protocols for TI Determination

Pre-Clinical In Vivo Protocol for TI Estimation

This protocol outlines the standard procedure for estimating the Therapeutic Index in animal models, a critical step in pre-clinical drug development [6].

- Objective: To determine the ED~50~ and LD~50~ of a novel drug candidate in a rodent model to calculate its pre-clinical Therapeutic Index.

- Test System: Laboratory-bred strain (e.g., Sprague-Dawley rats or CD-1 mice), typically 8-12 weeks old, with equal gender distribution.

Materials:

- Test compound

- Vehicle control

- Syringes and needles for injection

- Behavioral or functional test equipment (e.g., hot plate for analgesics)

- Clinical observation sheets

Procedure:

- Dose Range-Finding: Conduct a preliminary study with a small number of animals (e.g., n=3 per dose) across a wide dose range (e.g., 10, 100, 1000 mg/kg) to estimate the approximate range of efficacy and lethality.

- Main Study - Group Allocation: Based on range-finding, select at least 4-5 logarithmically spaced doses. Assign animals randomly to dose groups (n=8-10 is common).

- Dosing: Administer the drug via the intended clinical route (e.g., oral gavage, intraperitoneal injection).

- Efficacy Assessment (ED~50~):

- At a predetermined time post-dose (T~max~), expose animals to a test measuring the desired therapeutic endpoint (e.g., time to pain response).

- A positive "quantal" effect is recorded if the animal's response meets a pre-defined criterion (e.g., ≥50% increase in response latency).

- Record the proportion of animals in each dose group showing a positive therapeutic effect.

- Toxicity/Lethality Assessment (LD~50~):

- Observe animals continuously for the first 4 hours post-dose and then periodically for 14 days.

- Record specific signs of toxicity (e.g., convulsions, paralysis) and mortality.

- The endpoint for LD~50~ is death within the 14-day observation period.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot two separate quantal dose-response curves: one for the therapeutic effect and one for lethality.

- Use probit analysis or non-linear regression (logistic function) to fit sigmoidal curves to the data.

- From the fitted curves, calculate the ED~50~ and LD~50~ values and their 95% confidence intervals.

- Calculate the Therapeutic Index as TI = LD~50~ / ED~50~.

Clinical TI and Therapeutic Window Determination

In clinical practice, the TI is often redefined using parameters more relevant to humans, moving from doses (ED~50~/TD~50~) to drug concentrations in the blood (MEC/MTC) [23] [15] [4]. This reflects the understanding that drug effects correlate better with plasma concentration than with administered dose.

- Objective: To define the therapeutic window for an approved drug in a patient population.

- Study Design: Population pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic (PopPK/PD) analysis of data from Phase II/III clinical trials, often supplemented with therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) data from post-marketing surveillance.

- Key Parameters:

- Minimum Effective Concentration (MEC): The lowest plasma concentration at which the drug's therapeutic effect is observed.

- Minimum Toxic Concentration (MTC): The plasma concentration at which unacceptable adverse effects begin to occur.

- Procedure:

- Data Collection: Collect dense PK/PD data from controlled trials and sparse TDM data from clinical practice.

- Efficacy Endpoint Analysis: Model the relationship between drug exposure (e.g., trough concentration, AUC) and a primary efficacy endpoint (e.g., prevention of graft rejection for immunosuppressants) [23].

- Toxicity Endpoint Analysis: Model the relationship between the same exposure metrics and the incidence of a key adverse drug reaction.

- Determine Concentration Ranges: Establish the population-average concentration range where most patients experience efficacy with minimal toxicity. The clinical TI is sometimes expressed as TI = MTC / MEC [4].

- Define the Therapeutic Window: The range of plasma concentrations between the MEC and the MTC is the therapeutic window, which provides direct guidance for dosing and TDM in patients [6] [14].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Therapeutic Indices of Common Drugs

The therapeutic index varies dramatically among different drug classes. The table below summarizes the TI for several well-known drugs, illustrating the wide spectrum of drug safety margins [1].

| Drug | Therapeutic Index (TI) | Clinical Implications |

|---|---|---|

| Remifentanil | 33,000 : 1 | Extremely wide safety margin; considered very safe within its intended use. |

| Diazepam | 100 : 1 | Relatively wide safety margin. |

| Morphine | 70 : 1 | Moderate safety margin; requires careful dosing. |

| Cocaine | 15 : 1 | Narrow safety margin; high risk of toxicity. |

| Ethanol | 10 : 1 | Narrow safety margin. |

| Paracetamol (Acetaminophen) | 10 : 1 | Narrow safety margin; overdose can cause severe liver damage. |

| Digoxin | 2 : 1 | Very narrow safety margin; requires therapeutic drug monitoring. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Successful determination of the therapeutic index relies on specific research tools and reagents. The following table details essential items used in the experimental protocols described above.

| Item | Function in TI Research |

|---|---|

| Laboratory Animals (e.g., Rodents) | In vivo test system for determining ED~50~ and LD~50~; chosen based on genetic uniformity and physiological relevance [6]. |

| Test Compound & Vehicle | The investigational drug and the solution used to dissolve/suspend it (e.g., saline, DMSO, carboxymethyl cellulose) for accurate dosing. |

| Behavioral Apparatus (e.g., Hot Plate, Rotarod) | Equipment to provide a standardized, quantal measure of the drug's therapeutic efficacy (e.g., analgesia, sedation) [6]. |

| Clinical Chemistry & Hematology Analyzers | Used to assess organ-specific toxicities (e.g., liver enzymes, renal function) as endpoints for TD~50~, beyond overt lethality. |

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Gold-standard analytical technique for measuring drug concentrations in plasma for clinical TI and therapeutic window studies [23]. |

| Probit Analysis Software | Statistical software package used to fit sigmoidal curves to quantal dose-response data and accurately calculate ED~50~, LD~50~, and their confidence intervals [6]. |

| Roginolisib | Roginolisib, CAS:1305267-37-1, MF:C26H27FN4O5S, MW:526.6 g/mol |

| MAO-B-IN-8 | (2Z)-6-hydroxy-2-(2,3,4-trimethoxybenzylidene)-1-benzofuran-3(2H)-one |

Regulatory and Clinical Significance

Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) Drugs

Drugs with a low TI are classified as Narrow Therapeutic Index (NTI) drugs. Regulatory bodies like the US FDA define NTI drugs as those where there is less than a 2-fold difference in the LD~50~ and ED~50~ (or MTC and MEC), and whose safe use requires careful titration and patient monitoring [15] [4]. For these drugs, small changes in dose or blood concentration can lead to serious therapeutic failure or severe, life-threatening adverse drug reactions [15]. The following diagram illustrates the critical differences between drugs with a wide and narrow TI.

Examples of NTI drugs include warfarin, lithium, digoxin, phenytoin, and theophylline [11] [14]. For instance, cyclosporine, an immunosuppressant, has a TI estimated between 2 and 3, placing it just at the threshold of being an NTI drug [23].

Impact on Drug Development and Regulation

The TI, particularly the classification of a drug as NTI, has direct consequences on regulatory policy, especially for the approval of generic drugs [15] [4].

- Standard Bioequivalence (BE): For most drugs, generic versions must demonstrate that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of their geometric mean exposure (AUC and C~max~) to the brand-name product falls within 80-125% [15].

- Stringent BE for NTI Drugs: Due to the high risk associated with small variations in NTI drugs, regulatory authorities like the FDA have proposed more stringent standards. This may involve narrowing the BE limits (e.g., from 80-125% to 90-111%) or using a reference-scaled average bioequivalence approach that accounts for the low within-subject variability characteristic of NTI drugs [15] [4].

- Therapeutic Drug Monitoring (TDM): In clinical practice, NTI drugs almost universally require TDM, where a patient's drug plasma levels are measured to ensure they remain within the therapeutic window, thus maximizing efficacy and minimizing toxicity [1] [15].

Limitations and Advanced Considerations

While the TI = TD~50~/ED~50~ is a valuable initial metric, it has significant limitations that scientists and clinicians must consider.

- Reliance on Animal Data (LD~50~): The classical TI often uses LD~50~ from animal studies, which may not accurately predict human toxicity risks from sublethal adverse effects [5] [6].

- Ignores Slope of Curves: The TI is a single ratio and does not account for the slopes of the dose-response curves for efficacy and toxicity. If the curves are not parallel, a drug with a high TI could still produce toxicity in a subset of patients at doses effective for the majority [6] [14].

- Idiosyncratic Reactions: The TI cannot predict unpredictable, non-dose-related adverse drug reactions, such as allergic reactions or idiosyncratic toxicities [5] [6].

- Individual Variability: The TI is a population-average measure. It does not capture inter-individual variability due to genetics (pharmacogenomics), age, organ function, or drug interactions, which can drastically alter a drug's effective and toxic doses for a single patient [5] [15] [4].

To address these limitations, more sophisticated safety metrics have been proposed, such as the Certain Safety Factor (CSF = TD~1~/ED~99~), which uses the doses at which a drug is effective in 99% of the population and toxic in 1% of the population, providing a more conservative and clinically relevant safety estimate [14]. Modern drug development increasingly relies on exposure-based TI calculations (using AUC and C~max~) and PK/PD modeling to create a more robust and predictive safety profile for new drug candidates [1] [15].

The therapeutic index (TI) is a quantitative measurement of the relative safety of a drug, providing a critical ratio that compares the drug's exposure level that causes toxicity to the exposure level that produces the desired therapeutic effect [1]. This concept is a cornerstone of drug safety and is indispensable during clinical trials and the post-market monitoring phase [3]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding and accurately calculating the TI is paramount for selecting viable drug candidates and optimizing their safety profiles. The TI serves as a key parameter in balancing the potential benefits of a drug with its risks, guiding dose selection for clinical studies and informing prescribing guidelines [2]. A drug with a high TI has a wide margin of safety, whereas a drug with a narrow therapeutic index (NTI) requires much more careful dosing and monitoring, as small changes in blood concentration can lead to adverse effects or therapeutic failure [3] [24].

Core Principles and Calculations

Fundamental Formulas and Terminology

Classically, the therapeutic index is calculated using median effective and toxic doses. In pre-clinical animal studies, the lethal dose (LDâ‚…â‚€) might be used, while in clinical development, the toxic dose (TDâ‚…â‚€) is more relevant [1] [5]. The most common formula for the safety-based therapeutic index is:

TI = TDâ‚…â‚€ / EDâ‚…â‚€

Where:

- TDâ‚…â‚€ is the dose that produces a toxic effect in 50% of the population.

- EDâ‚…â‚€ is the dose that produces the desired therapeutic effect in 50% of the population [3] [5].

An alternative calculation is the efficacy-based therapeutic index, expressed as TIₑᶠᶠᶦᶜᵃᶜʸ = ED₅₀ / TD₅₀. In this case, a lower value indicates a larger therapeutic window [1]. The inverse of this, TD₅₀/ED₅₀, is known as the protective index [1].

It is crucial to note that in modern drug development, the TI is increasingly calculated based on plasma exposure levels (e.g., AUC or Cmax) rather than administered dose, as exposure more accurately reflects the pharmacological and toxicological effects experienced by the patient [2] [1].