Traditional vs. Mechanism-Based PK Modeling: A Strategic Guide for Drug Development

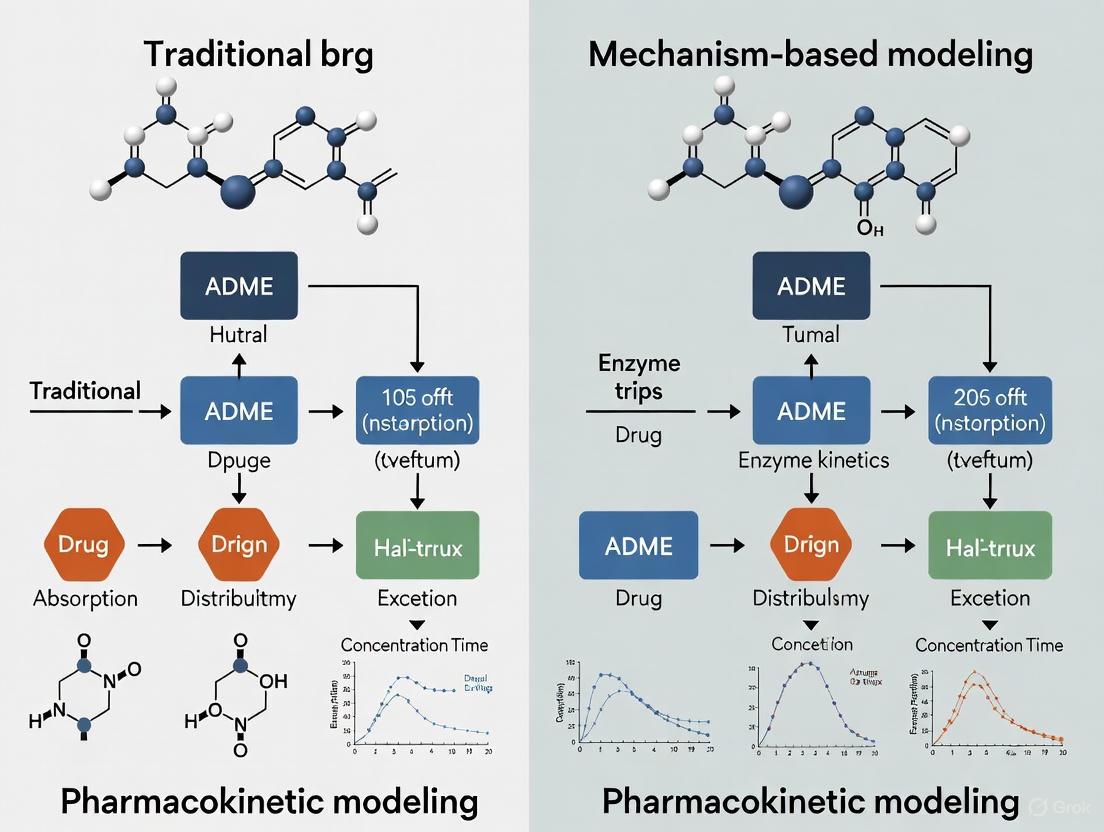

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals between traditional (compartmental, non-compartmental) and mechanism-based (PBPK, PK/PD) pharmacokinetic modeling approaches.

Traditional vs. Mechanism-Based PK Modeling: A Strategic Guide for Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison for researchers and drug development professionals between traditional (compartmental, non-compartmental) and mechanism-based (PBPK, PK/PD) pharmacokinetic modeling approaches. We explore their foundational principles, methodological applications, and strategic selection criteria. Drawing on recent studies and trends, the content synthesizes key differentiators, practical implementation challenges, and validation paradigms. The objective is to equip scientists with the knowledge to select the optimal modeling framework for enhancing predictive accuracy, streamlining development, and informing critical decisions from preclinical translation to clinical dose optimization.

Core Concepts: Defining Traditional Empiricism and Mechanistic Principles in PK Modeling

What is Pharmacokinetic Modeling? Defining the ADME Framework

Pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling is a mathematical discipline that quantifies how the body absorbs, distributes, metabolizes, and excretes a drug. By describing the time course of drug concentrations in the body, these models are indispensable for predicting efficacy, optimizing dosing regimens, and ensuring patient safety during drug development [1]. The foundation of pharmacokinetics is the ADME framework, which encompasses the key processes a drug undergoes after administration.

This guide compares two fundamental approaches in the field: traditional compartmental modeling and advanced mechanism-based modeling, providing researchers with a clear analysis of their methodologies, applications, and performance.

The ADME Framework: Core of Pharmacokinetics

The ADME framework describes the journey of a drug through the body, with each process influencing the drug's concentration at its site of action [1].

- Absorption: This is the process by which a drug enters the systemic circulation from its site of administration (e.g., the gastrointestinal tract for an oral drug). Factors like formulation and food effects can significantly impact the rate and extent of absorption, determining the drug's bioavailability [1].

- Distribution: Once in the bloodstream, the drug is distributed to various tissues and fluids. This process is influenced by blood flow, tissue permeability, and the degree of plasma protein binding, which affects how much free drug is available to exert its effect [1].

- Metabolism: The body typically transforms drugs into more water-soluble metabolites, primarily in the liver. Metabolism can inactivate a drug, activate a prodrug, or sometimes produce toxic metabolites. The cytochrome P450 enzyme family is a major player in this process [2] [1].

- Excretion: This is the removal of the drug and its metabolites from the body, occurring mainly through the kidneys (urine) or liver (bile) [1].

The following diagram illustrates the interconnected nature of these processes and their relationship with pharmacodynamics (PD), which studies the drug's effect on the body.

Traditional vs. Mechanism-Based Pharmacokinetic Modeling

The core difference between traditional and modern PK modeling lies in their descriptive versus predictive nature. The table below summarizes the key characteristics of each approach.

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional and Mechanism-Based PK Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Traditional Compartmental Modeling | Mechanism-Based PBPK/PKPD Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Core Philosophy | Empirically describes plasma concentration-time data [3] | Mechanistically simulates biological and drug-specific processes [4] [5] |

| Model Structure | Abstract "compartments" not directly tied to physiology (e.g., central, peripheral) [3] | Physiologically realistic structure representing organs/tissues with blood flows [6] [5] |

| Primary Output | Estimates of model parameters (e.g., clearance, volume of distribution) [3] | Prediction of drug concentrations in specific tissues and the impact of system perturbations [6] [7] |

| Extrapolation Power | Limited; relies on data from similar scenarios [4] | High; can extrapolate across populations, diseases, and dosing regimens by altering system parameters [6] [4] |

| Key Application | Population PK (PopPK) analysis to identify sources of variability in patient exposure [3] [8] | Predicting drug-drug interactions (DDIs), first-in-human dosing, and effects in special populations [6] [5] [2] |

The Evolution to Mechanism-Based Models

Mechanism-based pharmacokinetic-pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling represents a significant advancement. Unlike empirical models that merely describe data, mechanism-based models incorporate specific expressions to characterize the causal path between drug administration and its effect [4]. This includes:

- Target Occupancy: Modeling the binding of a drug to its molecular target (e.g., receptors, enzymes) [4].

- Target Activation: Quantifying the signal transduction processes that follow target binding [4] [9].

- Disease Progression: Integrating models of how a disease evolves over time and how a drug modifies this progression [7].

This mechanistic foundation provides vastly improved properties for extrapolation and prediction, forming a scientific basis for rational drug discovery and development [4].

Experimental Data and Model Performance Comparison

Case Study 1: PBPK for Drug-Drug Interaction (DDI) Prediction

A study developed a PBPK model for suraxavir marboxil (GP681), a prodrug, and its active metabolite (GP1707D07) to assess DDI risk with CYP3A4 inhibitors [2].

- Methodology: The model was built using in vitro physicochemical and metabolic parameters and verified against clinical data from a phase I DDI study with the strong inhibitor itraconazole [2].

- Results: The validated model predicted a significant increase in the active metabolite's exposure when co-administered with moderate inhibitors like fluconazole (AUC ratio 2.82) and verapamil (AUC ratio 2.35), comparable to the effect of itraconazole [2]. This demonstrates the utility of PBPK modeling for efficient DDI assessment without the need for multiple clinical trials.

Case Study 2: PBPK for Pediatric Dose Selection

A PBPK model was developed for ALTUVIIIO, a novel hemophilia A therapy, to support dosing in children under 12 [5].

- Methodology: A minimal PBPK model for monoclonal antibodies was used, incorporating the FcRn recycling pathway. The model was first validated using clinical data from a similar drug (ELOCTATE) by optimizing age-dependent parameters like FcRn abundance [5].

- Results: The model accurately predicted exposure in both adults and children, with prediction errors for key metrics (Cmax and AUC) within ±25%, confirming its utility for pediatric dose justification before clinical data collection [5].

Quantitative Model Performance Metrics

When comparing PopPK models, especially for clinical Model-Informed Precision Dosing (MIPD), performance is evaluated using specific metrics. The following table outlines the key metrics and why the forecasting approach is considered the gold standard for real-world applicability [10].

Table 2: Key Metrics for Evaluating Pharmacokinetic Model Performance

| Metric | Definition | Interpretation in PK Context | Gold Standard Approach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bias (MPE) | Mean Prediction Error: Average difference between predicted and observed concentrations [10] | Measures whether a model consistently under- or over-predicts drug levels. Ideal value is 0 [10]. | Forecasting future drug levels (Approach 3) [10] |

| Accuracy (e.g., % within range) | Percentage of predictions within a pre-defined acceptable range (e.g., within 15% of the observed value) [10] | A more critical measure than bias; indicates the proportion of clinically usable predictions. Higher is better [10]. | Forecasting future drug levels (Approach 3) [10] |

| AIC/BIC | Akaike/Bayesian Information Criterion: Penalizes the model's objective function value for complexity [3] | Used for structural model selection during development. Lower values indicate a better balance of fit and parsimony [3]. | Model fitting to historical data (Approach 2) [10] |

Research Toolkit: Essential Methods and Reagents

Successful PK modeling relies on a combination of in silico, in vitro, and in vivo tools.

Diagram: Integrated Workflow in Modern PK Modeling

Key Research Reagents and Solutions

| Tool / Reagent | Function in PK Modeling |

|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS (Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry) | Gold-standard analytical method for the sensitive and specific quantification of drug and metabolite concentrations in biological samples (e.g., plasma, tissues) [1]. |

| Recombinant CYP Enzymes / Human Hepatocytes | In vitro systems used to characterize a drug's metabolic stability, identify metabolizing enzymes, and obtain parameters (e.g., Km, Vmax) for PBPK models [2]. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing | Technology to create novel animal models (e.g., humanized enzyme rats) for studying the specific role of genetic factors in drug metabolism and transport [6]. |

| NLME Software (e.g., NONMEM) | Industry-standard software for performing population PK analysis using non-linear mixed-effects models, which handle sparse and dense data from diverse populations [3] [8]. |

| PBPK Software Platforms (e.g., GastroPlus, Simcyp) | Commercial platforms containing extensive physiological and demographic databases to build, simulate, and verify PBPK models for prediction in virtual populations [6] [5]. |

| Leu-Enkephalin amide | Leu-Enkephalin amide, MF:C28H38N6O6, MW:554.6 g/mol |

| DAMGO TFA | DAMGO TFA, MF:C28H36F3N5O8, MW:627.6 g/mol |

The evolution from traditional compartmental models to mechanism-based PBPK and PK/PD modeling marks a paradigm shift in drug development. While traditional PopPK remains valuable for analyzing variability in observed clinical data [3] [8], mechanism-based models offer superior predictive power for de-risking development [6] [4]. The integration of these models with artificial intelligence and machine learning is further automating and enhancing their capabilities, promising even faster and more effective development of safe, personalized therapies [6] [8]. The choice between approaches is not mutually exclusive; rather, they are complementary tools that, when used together, provide a comprehensive quantitative framework for informed decision-making from the lab to the clinic.

In the evolving landscape of model-informed drug development (MIDD), traditional pharmacokinetic analysis methods remain fundamental tools for characterizing drug behavior in vivo [11]. Compartmental modeling and non-compartmental analysis (NCA) represent two cornerstone approaches for quantifying drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties [12]. While mechanism-based approaches like physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling continue to advance, compartmental and NCA methods provide the critical foundation for understanding fundamental pharmacokinetic parameters [7] [5]. These traditional frameworks continue to play essential roles across drug discovery, preclinical development, and clinical trials, supporting critical decisions from lead optimization to dosage selection [11] [13].

The strategic selection between compartmental modeling and NCA depends largely on the specific research questions, available data quality, and intended application of results [11] [12]. Both approaches offer distinct advantages and limitations, making them suitable for different contexts of use throughout the drug development pipeline. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these traditional pharmacokinetic analysis methodologies, their experimental applications, and their positioning within the broader framework of modern pharmacometric approaches.

Theoretical Foundations and Key Concepts

Non-Compartmental Analysis (NCA)

Non-compartmental analysis is a model-independent approach that calculates pharmacokinetic parameters directly from observed concentration-time data without assuming a specific structural model [14] [12]. This method provides a straightforward determination of exposure metrics without requiring prior knowledge of the drug's underlying distribution characteristics [12]. NCA is particularly valuable for its simplicity, reduced potential for model-based bias, and ability to generate actionable parameters quickly [14].

Key NCA Parameters:

- C~max~: The peak concentration observed during a dosing interval, crucial for understanding safety and acute effects [14]

- AUC (Area Under the Curve): A measure of total drug exposure, highly relevant to therapeutic and toxic effects [14]

- T~max~: The time to reach maximum concentration [14]

- Terminal Half-Life: The time required for plasma concentration to decrease by 50% during the terminal phase [14]

Compartmental Analysis

Compartmental modeling divides the body into one or more hypothetical compartments, representing groups of tissues with similar distribution characteristics [12]. Unlike NCA, this approach employs mathematical models to describe the kinetics of drug transfer between compartments and elimination from the body [12]. Compartmental models range from simple one-compartment structures to complex multi-compartment systems that more accurately represent drug distribution patterns [12].

Model Progression:

- One-Compartment Model: Simplifies the body to a single homogeneous unit [12]

- Two-Compartment Model: Distinguishes between central (plasma and highly perfused tissues) and peripheral (poorly perfused tissues) compartments [12]

- Three-Compartment Model: Further separates distribution into plasma, highly perfused tissues, and scarcely perfused tissues [12]

- Population PK (PopPK): Extends compartmental modeling to quantify and explain variability in drug exposure across individuals [15]

Methodological Comparison: NCA vs. Compartmental Analysis

The table below summarizes the fundamental characteristics, advantages, and limitations of each approach.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison Between NCA and Compartmental Analysis

| Characteristic | Non-Compartmental Analysis (NCA) | Compartmental Analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Theoretical Basis | Model-independent; based on statistical moments [12] | Model-dependent; based on hypothetical compartments [12] |

| Structural Assumptions | No compartmental structure assumed [14] | Assumes specific number and arrangement of compartments [12] |

| Data Requirements | Rich sampling preferable for accurate AUC [14] | Can accommodate sparse data through population approaches [15] |

| Primary Outputs | Direct exposure parameters (AUC, C~max~, half-life) [14] | Model parameters (clearance, volume, rate constants) [12] |

| Key Strengths | Simplicity, speed, reduced model bias [14] | Predictive capability for different scenarios [12] |

| Major Limitations | Limited extrapolation beyond observed data [14] | Model misspecification risk, complexity [12] |

Regulatory Context and Parameter Usage

Regulatory agencies including the FDA and EMA rely heavily on specific NCA parameters for critical decisions. For bioequivalence assessments, food effect evaluations, and drug-drug interaction studies, regulators primarily focus on C~max~ and AUC~last~ values rather than parameters derived from terminal slope estimations [14]. This regulatory preference underscores the importance of well-designed sampling schemes to generate reliable NCA parameters for submission packages.

Experimental Applications and Case Studies

Protocol: NCA in Formulation Development

Objective: Compare pharmacokinetic profiles of novel extended-release (ER) ketorolac tromethamine tablet-in-tablet (TIT) formulation versus conventional immediate-release (IR) tablets [16].

Methodology:

- Study Design: Single-dose, crossover study in beagle dogs (n=18) [16]

- Formulations: Conventional IR tablets (10 mg) vs. novel ER TIT formulation [16]

- Dosing: Oral administration after 12-hour fast [16]

- Blood Sampling: Serial blood collection at predetermined time points [16]

- Bioanalysis: LC-MS/MS quantification of ketorolac plasma concentrations [16]

- NCA Parameters: C~max~, T~max~, AUC~last~, AUC~inf~, half-life [16]

Key Findings: The TIT formulation demonstrated extended-release characteristics with significantly longer T~max~ (5 h vs. 1 h) and lower C~max~ compared to conventional tablets, confirming the feasibility of once-daily dosing [16].

Protocol: Population PK (PopPK) in Clinical Development

Objective: Develop a population pharmacokinetic model for subcutaneous nivolumab to support non-inferiority assessment against intravenous formulation [17].

Methodology:

- Study Design: Phase III trial (CheckMate 67T) in patients with renal cell carcinoma [17]

- Modeling Approach: Population PK using NONMEM with PRIOR subroutine [17]

- Data Integration: Leveraged extensive historical nivolumab PK data across tumor types [17]

- Exposure Metrics: Time-averaged serum concentration over first 28 days (C~avgd28~) and steady-state trough concentration (C~minss~) [17]

- Validation: Clinical trial simulations to assess robustness [17]

Key Findings: Model-based analysis provided more accurate exposure estimates than NCA, demonstrating non-inferiority of subcutaneous administration and supporting regulatory approval [17].

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 2: Essential Research Materials for Traditional PK Studies

| Material/Resource | Function/Application | Example Context |

|---|---|---|

| LC-MS/MS System | Bioanalytical quantification of drug concentrations in biological matrices [16] | Ketorolac plasma concentration measurement [16] |

| NONMEM Software | Non-linear mixed effects modeling for population PK analysis [17] [15] | Subcutaneous nivolumab PPK model development [17] |

| Stable Isotope IS | Internal standard for bioanalytical method accuracy [16] | [²H₅]-Ketorolac as internal standard [16] |

| PK Sampling Scheme | Strategic blood collection timepoints for rich or sparse data [14] | Optimal sampling for reliable AUC estimation [14] |

| Geraniin (Standard) | Geraniin (Standard), MF:C41H28O27, MW:952.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| PAR-4 Agonist Peptide, amide TFA | PAR-4 Agonist Peptide, amide TFA, MF:C36H49F3N8O9, MW:794.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integration with Modern Modeling Approaches

Traditional PK analysis methods are increasingly integrated with advanced modeling approaches within the MIDD paradigm [11]. The selection between NCA and compartmental modeling follows a "fit-for-purpose" principle, aligning the methodology with specific research questions and context of use [11].

Strategic Implementation:

- Early Discovery: NCA for rapid screening of formulations or lead compounds [13]

- Preclinical Development: Compartmental modeling for interspecies scaling and first-in-human dose prediction [13]

- Clinical Development: Population PK to quantify variability and identify covariates [15]

- Regulatory Submission: Hybrid approaches incorporating both NCA and model-based analysis [17] [5]

This integrated approach enables more efficient drug development, with traditional methods providing foundational exposure data that informs mechanism-based models including PBPK and quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) [11] [7].

Visual Guide: Method Selection and Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the decision-making process for selecting between NCA and compartmental analysis, and their positioning within the modern MIDD framework.

Diagram 1: PK Method Selection in Modern Drug Development

Both non-compartmental and compartmental analyses maintain critical positions in contemporary pharmacokinetic research and drug development. NCA provides unbiased exposure assessment essential for regulatory decision-making, while compartmental modeling enables predictive simulations and population-based variability analysis [17] [14]. The strategic integration of these traditional approaches with emerging mechanism-based methodologies represents the future of efficient, scientifically rigorous drug development [11] [5].

Understanding the appropriate context of use for each method allows researchers to construct a comprehensive pharmacokinetic assessment strategy that progresses from traditional exposure assessment to sophisticated predictive modeling, ultimately accelerating the development of safe and effective therapeutics [11] [13].

Pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling is a cornerstone of modern drug development, enabling researchers to understand a drug's behavior in the body. This guide compares traditional compartmental PK modeling with mechanism-based approaches, primarily Physiologically Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) and Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling. While traditional models offer a simplified, empirical description of drug concentrations, mechanism-based models integrate physiological, biological, and pharmacological details to provide a mechanistic understanding of drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion (ADME), and effect. This comparison explores the fundamental principles, applications, and experimental protocols for each approach, providing researchers with the data needed to select the appropriate tool for their development challenges.

Pharmacokinetic modeling is a mathematical technique used to quantify and predict the fate of pharmaceutical compounds in the body [18]. In drug development, these models are critical for reducing failure rates and increasing the efficiency of bringing new therapies to market. The evolution of PK modeling has progressed from traditional, empirical methods to more sophisticated, mechanism-based frameworks that align with the goals of Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD).

Traditional compartmental models view the body as a series of interconnected compartments, typically one or two, that do not necessarily correspond to specific anatomical entities. These models are "top-down," starting from observed clinical plasma concentration-time data to estimate parameters like clearance and volume of distribution [19]. Their strength lies in their simplicity and efficiency in characterizing average drug behavior in a population.

In contrast, mechanism-based models, including PBPK and PK/PD models, adopt a "bottom-up" approach. PBPK models represent the body as a network of anatomically meaningful compartments (e.g., liver, kidney, brain) linked by the circulatory system. They incorporate independent prior knowledge of human physiology and the drug's physicochemical properties to achieve a mechanistic representation of ADME processes [20]. PK/PD modeling extends this further by linking the drug concentration at the site of action (predicted by PBPK or other PK models) to the magnitude of the pharmacological effect, creating a multiscale model that describes both drug behavior and its impact on the biological system [20] [7].

The following sections provide a detailed, data-driven comparison of these paradigms, highlighting their respective roles in advancing drug development.

Comparative Analysis: Traditional vs. Mechanism-Based Modeling

The table below summarizes the core characteristics of traditional population PK (PopPK), PBPK, and integrated PBPK/PD models, providing a clear, structured comparison.

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of Pharmacokinetic Modeling Approaches

| Feature | Traditional PopPK Models | Mechanism-Based PBPK Models | Integrated PBPK/PD Models |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Empirical, "top-down"; data-driven [19] | Mechanistic, "bottom-up"; physiology-driven [20] [19] | Multiscale and mechanistic; integrates physiology and pharmacology [20] |

| Structural Basis | Abstract compartments (central, peripheral) without direct physiological correspondence [18] | Anatomically meaningful compartments representing specific organs and tissues [20] | PBPK structure linked to a pharmacodynamic model describing the drug's effect [20] |

| Key Input Parameters | Observed clinical PK data; patient covariates (weight, renal function) [19] | Drug physicochemical properties (lipophilicity, pKa), in vitro data, and physiological parameters (organ volumes, blood flows) [20] | All PBPK inputs, plus PD parameters (e.g., Emax, EC50) derived from in vitro or in vivo effect data [21] |

| Primary Outputs | Population estimates of CL, Vd, and inter-individual variability [8] | Concentration-time profiles in plasma and specific tissues/organs [20] | Concentration-time and effect-time profiles; prediction of efficacy and toxicity [21] |

| Typical Applications | Dose optimization, identifying covariate relationships, study design [22] [8] | Predicting drug-drug interactions (DDI), extrapolation to special populations (pediatric, organ impairment), formulation assessment [20] [23] [5] | Target engagement analysis, dose selection to maximize efficacy/safety, preclinical to clinical translation [20] [21] |

Workflow and Application Comparison

The fundamental difference in approach leads to distinct workflows, as illustrated in the diagrams below.

Traditional Empirical Modeling Workflow illustrates the standard top-down process for building population PK models.

Mechanistic PBPK Modeling Workflow shows the bottom-up process of building a physiologically-based model.

Experimental Protocols and Case Studies

Protocol: Building and Qualifying a PBPK Model

The "middle-out" approach for PBPK model development is commonly used, integrating in vitro and pre-clinical data, then refining with clinical data.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Platforms for PBPK/PK/PD Modeling

| Tool / Reagent | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Simcyp Simulator | Software Platform | Population-based PBPK simulator with extensive physiological and enzyme database [23]. |

| GastroPlus | Software Platform | PBPK modeling platform focused on absorption prediction and biopharmaceutics [20]. |

| NONMEM | Software Platform | Industry-standard software for non-linear mixed effects (population) PK/PD modeling [8]. |

| PK-Sim & MoBi | Software Platform | Whole-body PBPK modeling and model integration toolkit [20]. |

| Fraction Unbound (fu) | In Vitro Parameter | Measured fraction of drug unbound to plasma proteins; critical for estimating effective drug concentration [18]. |

| Tissue:Plasma Partition Coefficient (Kp) | In Vitro/Derived Parameter | Predicts the distribution of a drug into specific tissues relative to plasma [20]. |

Detailed Methodology:

- Parameter Collection: Gather the drug's physicochemical properties (molecular weight, lipophilicity expressed as Log P, acid dissociation constant pKa) and in vitro ADME data. This includes permeability, fraction unbound in plasma (fu), and metabolic clearance data from human liver microsomes or recombinant CYP enzymes [20] [23].

- Model Construction: Input these parameters into a PBPK software platform (e.g., Simcyp, GastroPlus). The platform uses built-in physiological databases (organ volumes, blood flow rates) and distribution models (e.g., Poulin and Theil) to estimate tissue-plasma partition coefficients (Kp) and build the initial model structure [20].

- Model Verification & Qualification: Simulate clinical PK studies (e.g., single-dose IV infusion) in a virtual population and compare the simulated concentration-time profiles to observed clinical data. Key metrics like AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (maximum concentration) are compared, typically aiming for a prediction within a 2-fold error range [23] [18].

- Model Application: Once qualified, the model is used for simulation and extrapolation. This includes predicting DDIs, exploring PK in special populations (e.g., pediatrics, renally impaired), or supporting dose selection for new clinical scenarios [20] [5].

Case Study: PBPK for Pediatric Dose Selection of a Novel Antibiotic

Objective: To predict an effective pediatric dose of gepotidacin for pneumonic plague where clinical trials in children are not feasible [23].

Experimental Protocol:

- Model Development: A gepotidacin PBPK model was constructed in Simcyp using physicochemical and in vitro data. The model was optimized using clinical PK data from a dose-escalation intravenous study in healthy adults [23].

- Model Qualification: The model was verified by simulating other adult clinical studies, including a human mass balance study, and comparing predictions to observed data [23].

- Pediatric Extrapolation: The qualified adult model was scaled to pediatric populations by incorporating age-dependent changes in physiology (organ sizes, blood flows), body composition, and the ontogeny (maturation) of key elimination pathways (CYP3A4 enzyme and renal function) [23].

- Dose Prediction: Simulations were run for various pediatric age and weight brackets. The proposed dosing regimen was weight-based for subjects ≤40 kg. The goal was for ~90% of the predicted pediatric exposure (AUC) to fall between the 5th and 95th percentiles of the effective adult exposure [23].

Supporting Data: The study reported that both PBPK and a traditional PopPK model could reasonably predict gepotidacin exposures in children, though they differed in predictions for children under 3 months old, highlighting PBPK's advantage in accounting for enzyme maturation [23].

Case Study: AI-Enhanced PBPK/PK/PD for Aldosterone Synthase Inhibitors

Objective: To predict the PK/PD properties of aldosterone synthase inhibitors (ASIs) from their structural formulas during early drug discovery to select candidates with high potency and selectivity [21].

Experimental Protocol:

- AI-PBPK Model Workflow: The protocol involved a multi-step workflow as shown in the diagram below.

- Model Calibration and Validation: Baxdrostat, the ASI with the most clinical data, was used as the model compound. The AI-predicted PK parameters were calibrated against its published clinical trial data. External validation was performed using data for other ASIs (Dexfadrostat, Lorundrostat) [21].

- PD Modeling: A pharmacodynamic model was developed based on the simulated free (unbound) plasma concentrations of each drug. An Emax model was used to predict the inhibition rate of the target enzyme (aldosterone synthase) and the off-target enzyme (11β-hydroxylase). The selectivity index (SI) was calculated as the ratio of the IC50 for the off-target to the IC50 for the target [21].

Supporting Data: The study demonstrated that the AI-PBPK model could infer the PK/PD properties of an ASI from its structural formula within a certain error range, providing a reference for early lead compound screening and optimization [21].

Regulatory Perspective and Future Directions

Regulatory agencies like the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) increasingly recognize the value of mechanism-based models. A landscape analysis of submissions to the FDA's Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research (CBER) from 2018 to 2024 shows a growing trend in the use of PBPK modeling, supporting applications for gene therapies, therapeutic proteins, and other biological products [5]. These submissions often aim to justify and optimize dosing, particularly in special populations like pediatrics, and to provide a mechanistic understanding of a drug's behavior [5].

The future of mechanism-based modeling is being shaped by several key advancements:

- Automation and Machine Learning: AI and automation are being applied to streamline model development. Automated PopPK tools can now identify optimal model structures from vast search spaces in a fraction of the time required for manual development [8]. As demonstrated in the case study, AI is also being integrated with PBPK models to predict ADME parameters directly from molecular structures, accelerating early drug discovery [21].

- Hybrid and Multi-Scale Models: The line between model types is blurring. Research confirms the compatibility between PBPK and traditional compartment models, showing that a PBPK model can be theoretically "lumped" into a simpler compartmental structure with similar predictive power for plasma concentrations [18]. This allows for more flexible, fit-for-purpose model development.

- Expansion into Novel Modalities: PBPK and PK/PD modeling are expanding beyond small molecules to support the development of complex biological products, including therapeutic proteins, monoclonal antibodies, cell and gene therapies, and mRNA therapeutics [5].

In the field of pharmacokinetics (PK), two dominant modeling philosophies compete and complement each other: the data-driven, empirical approach of traditional compartmental modeling and the mechanism-based, biology-driven approach of physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling. This guide provides an objective comparison for researchers and drug development professionals.

Philosophical Foundations and Core Applications

Empirical Curve-Fitting: Traditional Compartmental Modeling

This approach conceptualizes the body as a system of abstract mathematical compartments, often without direct physiological correlates. The primary goal is to find a mathematical model that best fits observed plasma concentration-time data. Population PK (PopPK) is a widely used implementation that employs nonlinear mixed-effects (NLME) models to characterize inter- and intra-individual variability in drug exposure [8].

Biology-Driven Simulation: Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) Modeling

PBPK modeling is structured on a mechanism-driven paradigm, representing the body as a network of physiological compartments (e.g., liver, kidney) interconnected by blood circulation. It integrates system-specific physiological parameters (e.g., organ weights, blood flow rates) with drug-specific properties (e.g., lipophilicity, protein binding) to quantitatively predict PK profiles [24].

Core Applications in Drug Development: PBPK modeling has gained substantial traction in regulatory submissions. An analysis of FDA-approved new drugs from 2020-2024 shows that 26.5% (65 of 245) of NDAs/BLAs included PBPK models as pivotal evidence [24]. Its applications are diverse, as shown in the table below.

Table: Primary Application Domains of PBPK Models in Regulatory Submissions (2020-2024)

| Application Domain | Proportion of Instances | Specific Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Drug-Drug Interactions (DDI) | 81.9% | Enzyme-mediated (e.g., CYP3A4), transporter-mediated (e.g., P-gp), acid-reducing agent effects [24]. |

| Dosing in Organ Impairment | 7.0% | Hepatic impairment (4.3%), renal impairment (2.6%) [24]. |

| Pediatric Dosing | 2.6% | Extrapolation from adult data using known physiological differences [24]. |

| Other (Food-effect, etc.) | 8.5% | Formulation development, bioequivalence studies [24]. |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for Automated Empirical PopPK Model Development

Modern approaches aim to automate the traditionally labor-intensive process of PopPK model development. The following workflow, enabled by tools like pyDarwin, can identify robust model structures in less than 48 hours on average [8].

Detailed Methodology [8]:

Define Model Search Space: A generic model space containing over 12,000 unique PopPK model structures for extravascular drugs is constructed. This space includes variations in:

- Number of compartments (1, 2, or 3)

- Absorption models (first-order, zero-order, transit compartments)

- Elimination models (linear and non-linear, e.g., Michaelis-Menten)

- Residual error models (e.g., additive, proportional, combined)

Run Optimization Algorithm: A machine learning-driven optimization (e.g., Bayesian optimization with a random forest surrogate) explores the model space. The algorithm efficiently evaluates a small fraction (<2.6%) of all possible models to identify promising candidates.

Model Evaluation and Selection: A custom penalty function is applied to select the final model. This function balances:

- Goodness-of-fit: Using criteria like Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) to prevent over-parameterization.

- Biological Plausibility: Penalizing abnormal parameter values (e.g., unrealistically high clearance or volume of distribution) that would be rejected by a domain expert.

Protocol for Developing and Qualifying a PBPK Model

The development of a biology-driven PBPK model is an iterative process of building, evaluating, and refining a mechanistic hypothesis.

Detailed Methodology [25] [24]:

System Data Collection: Gather human physiological parameters for the target population (e.g., organ volumes, blood flow rates, expression levels of enzymes/transporters). These can be specific to age, disease state, or other covariates.

Drug Data Collection: Obtain drug-specific parameters, ideally from in vitro assays. Key parameters include:

- Physicochemical properties: Lipophilicity (Log P), pKa, solubility.

- Binding data: Plasma protein binding.

- Metabolism/Transport: Kinetic parameters (e.g., V~max~, K~m~) from human liver microsomes or transfected cell lines for relevant enzymes and transporters.

Model Building & Implementation: Integrate system and drug data into a mathematical model structure, typically a system of ordinary differential equations (ODEs). The model can be implemented as a stand-alone application for a specific drug or using a flexible template or superstructure that can be configured for multiple chemicals [26].

Model Verification and Validation (V&V):

- Verification: Ensure the computer code correctly implements the intended mathematical model (quality assurance).

- Validation: Compare model simulations against observed clinical PK data not used for model building (e.g., from drug-drug interaction studies or special populations). This step is critical for establishing model credibility.

Model Application: The qualified model is used to simulate and predict drug exposure in untested clinical scenarios, such as complex DDIs, pediatric populations, or patients with organ impairment, to inform dosing recommendations and clinical trial design.

Performance Comparison: Quantitative Data

Predictive Accuracy and Regulatory Impact

Table: Comparison of Modeling Approaches Based on Published Data

| Performance Metric | Empirical PopPK / Curve-Fitting | Biology-Driven PBPK |

|---|---|---|

| Regulatory Acceptance (2020-2024) | Standard for exposure-response and dose justification. | Used in 26.5% of new drug approvals; dominant in DDI assessment (81.9% of PBPK applications) [24]. |

| Therapeutic Area Focus | Universal, applied across all disease areas. | Highest use in Oncology (42%), followed by Rare Diseases (12%) and CNS (11%) [24]. |

| Key Strength | Optimizes description of observed data; robust for interpolation within studied population. | Strong extrapolation capability to untested populations and conditions (e.g., pediatrics, organ impairment) [24]. |

| Primary Limitation | Limited extrapolation power; parameters lack direct physiological meaning [24]. | Relies on accurate in vitro to in vivo translation; model complexity can be high [25]. |

Computational Efficiency and Implementation

Computational performance is a key practical consideration, especially for large-scale simulations like Monte Carlo analyses.

Table: Computational and Implementation Factors

| Factor | Empirical PopPK | Biology-Driven PBPK |

|---|---|---|

| Model Development Time | Automated search can find robust structures in <48 hours [8]. | Development is typically longer, requiring extensive data collection and model qualification. |

| Simulation Speed | Generally fast, due to simpler model structures with fewer compartments. | Can be slower; a 30% computational time saving was achieved by fixing body weight parameters instead of treating them as time-varying [26]. |

| Software & Platforms | NONMEM, Monolix, nlmixr2, Pharmpy, pyDarwin [27] [8]. |

Simcyp (industry leader, ~80% usage), GastroPlus, Open Systems Pharmacology (OSP) suite [24] [28]. |

| Automation Potential | High (e.g., pyDarwin automates model structure search) [8]. |

Moderate. Template-based approaches (e.g., EPA's PBPK template) reduce implementation time and QA review burden [26]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Table: Key Tools and Platforms for PK Modeling

| Tool/Reagent | Function/Benefit | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| pyDarwin | An automated tool that uses optimization algorithms to efficiently search the PopPK model space [8]. | Automates the identification of the structural PopPK model from clinical data, reducing manual effort and improving reproducibility [8]. |

| PBPK Model Template | A pre-verified model "superstructure" containing common equations found in PBPK models [26]. | Accelerates the implementation of chemical-specific PBPK models and streamlines the quality assurance (QA) review process [26]. |

| Simcyp Simulator | The industry-leading platform for PBPK modeling and simulation [24]. | Used extensively for predicting drug-drug interactions and pharmacokinetics in virtual patient populations [24]. |

| R / nlmixr2 Package | An open-source environment for population PK/PD modeling and analysis [27]. | Used in a pipeline to compute initial parameter estimates for PopPK models, handling both rich and sparse data scenarios [27]. |

| Open Systems Pharmacology (OSP) | An open-source software suite that supports PBPK and quantitative systems pharmacology modeling [28]. | Used to develop a physiologically based biopharmaceutics model (PBBM) for vericiguat, integrating dissolution and solubility data [28]. |

| sn-Glycero-3-phosphocholine-d9 | sn-Glycero-3-phosphocholine-d9, MF:C8H20NO6P, MW:266.28 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Rifaximin-d6 | Rifaximin-d6, MF:C43H51N3O11, MW:791.9 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

Integrated Applications and Future Directions

The distinction between empirical and mechanistic modeling is blurring with the emergence of hybrid approaches and artificial intelligence (AI).

Synergistic Applications:

- Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD): Both PopPK and PBPK are pivotal MIDD tools. A "fit-for-purpose" strategy selects the appropriate tool based on the key question, context of use, and available data at different drug development stages [11].

- AI/ML Integration: Machine learning is being applied to both paradigms. For PopPK, it automates model development [8]. For PBPK, ML aids in parameter estimation, uncertainty quantification, and simplifying complex models, helping to address the "large parameter space" challenge [25] [29].

Future Outlook: The integration of PBPK modeling with AI and multi-omics data is poised to enhance predictive accuracy further [24]. The market growth of biosimulation, projected to reach $9.65 billion by 2029, underscores the increasing reliance on these in silico technologies to improve the efficiency and success rate of drug development [30].

In the field of pharmacokinetics (PK) and pharmacodynamics (PD), the traditional parameters of Area Under the Curve (AUC) and Maximum Concentration (Cmax) have long been foundational for assessing drug exposure in plasma. However, growing evidence underscores that these plasma-based metrics often fail to accurately predict clinical efficacy and toxicity, as they may not reflect drug concentrations at the site of action or account for complex pharmacological mechanisms [31]. This guide objectively compares the traditional reliance on AUC/Cmax with the more nuanced approaches of tissue distribution and receptor occupancy, framing the discussion within the broader thesis of traditional versus mechanism-based PK/PD modeling research. The integration of tissue exposure and target engagement parameters is critical, as slight structural modifications can significantly alter a drug's tissue selectivity and clinical profile without substantially changing its plasma PK [31].

Comparative Analysis of Key Parameters

The following tables summarize the core characteristics, experimental methodologies, and functional outputs of the discussed pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic parameters.

Table 1: Core Parameter Comparison

| Parameter | Definition | Primary Source Matrix | Key Strengths | Principal Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | The total drug exposure over time | Plasma/Serum | Standardized, high-throughput assays; Well-established regulatory acceptance [31] | Poor correlation with target tissue exposure; Relies on free drug hypothesis [31] |

| Cmax | The peak drug concentration after administration | Plasma/Serum | Simple to determine; Useful for assessing acute toxicity risk [31] | Single time-point metric; Does not inform on exposure duration |

| Tissue Distribution | Drug concentration in specific organs or tissues | Tissue Homogenate (e.g., tumor, liver, brain) | Directly measures exposure at the disease site; Can explain efficacy/toxicity discrepancies [31] | Invasive sampling; Complex, low-throughput methodologies [31] |

| Receptor Occupancy | The proportion of target receptors bound by a drug | Target Tissue (often inferred) | Directly measures target engagement; Links PK to pharmacological effect [32] | Technically challenging to measure in vivo; Requires specialized tools (e.g., PET ligands) [32] |

Table 2: Experimental and Output Comparison

| Parameter | Primary Experimental Methods | Key Output Metrics | Role in Model-Informed Drug Development (MIDD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC | Serial blood sampling followed by LC-MS/MS bioanalysis [31] | AUC0-t, AUC0-∞ | Input for traditional non-compartmental analysis (NCA) and PopPK models [23] |

| Cmax | Serial blood sampling followed by LC-MS/MS bioanalysis [31] | Cmax, Tmax | Used in dose selection and for setting safe starting doses in clinical trials |

| Tissue Distribution | Terminal tissue sampling, homogenization, and LC-MS/MS analysis [31] | Tissue-to-Plasma Ratio; Tissue Specific Selectivity Index [31] | Critical for verifying and refining PBPK models; Informs human tissue exposure predictions [31] [23] |

| Receptor Occupancy | Radioligand binding assays; Positron Emission Tomography (PET); Indirect Response PD Models [32] | % RO vs. Time; IC50 or Kd for binding | Central to mechanism-based PK/PD models; Enables prediction of clinical efficacy from in vitro potency [32] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol for Tissue Distribution Studies

A definitive tissue distribution study involves quantifying drug concentrations in various organs relative to plasma [31].

- Animal Model: Use relevant disease models (e.g., transgenic MMTV-PyMT mice for breast cancer studies) [31].

- Dosing and Sampling: Administer the drug (e.g., 5 mg/kg orally) and euthanize animals at predetermined time points (e.g., 0.08, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, 7 h). Collect blood (for plasma) and all tissues of interest (e.g., tumor, fat pad, bone, uterus, liver) [31].

- Sample Processing: Weigh and homogenize tissue samples. Precipitate proteins from plasma and tissue homogenates using ice-cold acetonitrile with an internal standard. Vortex and centrifuge the samples to obtain a clean supernatant [31].

- Bioanalysis: Analyze the supernatant using Liquid Chromatography with tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to determine the drug concentration in each matrix. Calculate tissue-to-plasma ratios and tissue selectivity indices [31].

Protocol for Assessing Receptor Occupancy via Indirect Response Models

Receptor occupancy can be inferred through integrated PK/PD modeling when direct measurement is infeasible [32].

- Pharmacokinetic Data: First, establish the plasma concentration-time profile (AUC, Cmax) of the drug in the test system.

- Pharmacodynamic Response: Measure a relevant, reversible pharmacological response that is directly mediated by the target receptor (e.g., prolactin release as a response to D2 receptor antagonism) [32].

- Model Fitting: Apply an indirect response model, where the drug inhibits or stimulates the production or loss of the PD marker. The model structure is defined by a set of differential equations (see Section 4.2).

- Parameter Estimation: Use software (e.g., NONMEM, Phoenix) to fit the model to the data, estimating the IC50 (concentration producing 50% of the maximum inhibitory effect). The estimated IC50 is a direct reflection of in vivo receptor affinity and occupancy [32].

Modeling Approaches: From Traditional to Mechanism-Based

Traditional Compartmental PK Modeling

Traditional models describe the body as a system of compartments, focusing solely on the time course of drug in plasma.

Traditional PK Model Workflow

Mechanism-Based PK/PD Modeling with Tissue Distribution and Receptor Occupancy

Mechanism-based models integrate drug-specific (e.g., tissue distribution, receptor binding) and system-specific (e.g., disease progression) parameters to predict the effect-time course.

Mechanism-Based PK/PD Integration

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Primary Function | Specific Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| Liquid Chromatography with tandem Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) | Highly sensitive and specific quantification of drug concentrations in complex biological matrices [31] | Measuring AUC from plasma and drug levels in tissue homogenates (e.g., tumor, bone) [31] |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Normalizes extraction efficiency and mitigates matrix effects during LC-MS/MS analysis [31] | Added to plasma and tissue homogenates during sample preparation for reliable bioanalysis [31] |

| Transgenic Animal Models | Provides a physiologically relevant in vivo system that mimics human disease for tissue distribution studies [31] | MMTV-PyMT mouse model for spontaneous breast cancer to study tumor penetration of SERMs [31] |

| PBPK Modeling Software (e.g., Simcyp) | Mechanistic platform that integrates in vitro and physiological data to predict PK in virtual human populations [23] | Predicting paediatric gepotidacin exposure and dose by incorporating age-dependent physiology [23] |

| Mechanism-Based PD Models | Mathematical frameworks (e.g., indirect response, signal transduction) that link drug exposure to pharmacological effect [32] | Modeling the time course of anticoagulant effect based on the inhibition of clotting factor synthesis [32] |

| Quetiapine-d8 Hemifumarate | Quetiapine-d8 Hemifumarate, MF:C25H29N3O6S, MW:507.6 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Belvarafenib TFA | Belvarafenib TFA, MF:C25H17ClF4N6O3S, MW:593.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis demonstrates that while traditional parameters like AUC and Cmax provide a essential foundation for understanding systemic exposure, they are insufficient alone for predicting clinical outcomes. The integration of tissue distribution data provides a critical link to understanding efficacy and toxicity at the target site, while receptor occupancy closes the loop by quantifying target engagement. The future of optimized drug development lies in the rigorous application of mechanism-based models that synthesize these multi-faceted parameters, moving beyond the limitations of traditional plasma-centric pharmacokinetics to a more holistic, predictive, and physiologically realistic framework.

Model in Action: Methodologies and Real-World Applications in Drug Development

In the field of pharmacokinetics (PK), the process of building a model revolves around two core, interdependent tasks: structural identification and parameter estimation. Structural identification involves determining the mathematical representation that best describes the drug's journey through the body—such as a one- or two-compartment model. Parameter estimation is the subsequent process of quantifying the rate constants, volumes of distribution, and clearances that define the chosen structure [3]. This guide focuses on characterizing traditional modeling approaches, primarily compartmental models and population pharmacokinetics (PopPK), and objectively compares them with emerging mechanism-based and machine-learning-driven methodologies.

Traditional pharmacometric models, often implemented via non-linear mixed-effects (NLME) modeling in software like NONMEM, are the established standard for informing dosing strategies and regulatory submissions [33] [8]. In contrast, mechanism-based models, such as Physiologically-Based Pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models, incorporate granular physiological details, while nascent machine learning (ML) approaches seek to automate and augment the model-building process [34] [35]. Understanding the capabilities and limitations of each approach is crucial for selecting the right tool in drug development.

Core Concepts and Methodologies

The Traditional Modeling Workflow: PopPK and Compartmental Models

The conventional process for building a PopPK model is often manual and iterative. It typically begins with a simple structural model (e.g., a one-compartment model), which is then progressively complexified—by adding compartments or alternative absorption models—until it adequately describes the observed data [33] [8].

- Structural Model Development: The structural model describes the typical concentration-time course within a population. Mammillary compartment models are predominant, where the number of compartments (one, two, or three) often corresponds to the number of distinct exponential phases observed in the log concentration-time curve. These models can be parameterized using derived rate constants or, preferentially, as volumes and clearances, which are more easily interpreted biologically [3].

- Statistical and Covariate Models: The statistical model accounts for "unexplainable" random variability, including between-subject, between-occasion, and residual variability. Covariate models explain variability by linking subject characteristics (e.g., weight, renal function) to model parameters [3].

- Parameter Estimation and Model Comparison: Parameter estimation is typically performed using maximum likelihood methods. The objective function value (OFV) is a key output used for model comparison. For nested models, the likelihood ratio test can be used, while for non-nested models, information criteria like the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) or Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) are employed, with lower values indicating a better fit while penalizing for model complexity [3].

Emerging Automated and Machine Learning Approaches

A modern alternative to the manual workflow is automated PopPK model development. One approach uses the pyDarwin library to search a vast pre-defined space of model structures. This method employs a penalty function that balances goodness-of-fit with model plausibility, using global optimization algorithms to efficiently identify suitable structures with minimal user configuration [33] [8].

Another innovative framework is the hierarchical ML approach, which operates in two steps: first, QSAR models predict PK parameters from chemical structures; second, another ML model uses these predicted parameters to forecast the full human PK profile [34].

Performance Comparison: Traditional vs. Emerging Methods

The table below summarizes a quantitative comparison of traditional and automated PopPK modeling approaches based on published studies.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Traditional vs. Automated PopPK Modeling

| Aspect | Traditional PopPK Modeling | Automated PopPK Modeling (pyDarwin) |

|---|---|---|

| Development Time | Manual, time-consuming; timelines depend on modeler expertise and data complexity [33]. | Average of <48 hours per model in a 40-CPU environment [33] [8]. |

| Model Search Strategy | Sequential, "greedy" local search; prone to finding local minima [33] [8]. | Global search (e.g., Bayesian Optimization); evaluates <2.6% of model space to find near-optimal solution [33] [8]. |

| Key Performance Metric | Relies on OFV, AIC, BIC, and biological plausibility assessed by an expert [3]. | Uses a custom penalty function combining AIC and plausibility checks on parameter values [33] [8]. |

| Reproducibility | Subject to variation based on individual modeler's decisions and preferences [33]. | High; the automated process explicitly encodes selection criteria, standardizing results [33] [8]. |

| Primary Advantage | Mechanistic interpretability; deep expert oversight. | Speed, exhaustive search, and reduced manual effort. |

The performance of traditional QSAR models in predicting physicochemical and PK parameters is well-established. For instance, a recent study demonstrated that consensus QSAR models could predict human clearance (CL) and volume of distribution at steady state (VDss) within a 2-fold error for 62-64% of test compounds [34]. When these parameters were used in a hybrid ML-PBPK framework, the prediction accuracy for human AUC and Cmax was within a 2-fold error for 40-60% of compounds and within a 5-fold error for 80-90% of compounds [34].

Table 2: Predictive Performance of QSAR Models for Key PK Parameters

| PK Parameter | Best Model Algorithm | Geometric Mean Fold Error (GMFE) | % Compounds within 2-fold Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fraction Unbound (Fu) | SVM with Merged Descriptors [34] | 2.01 [34] | 60% [34] |

| Clearance (CL) | Consensus Model [34] | 2.00 [34] | 64% [34] |

| Volume of Distribution (VDss) | Consensus Model [34] | 1.88 [34] | 62% [34] |

Beyond model building, the choice of modeling framework significantly impacts outcomes in applied fields like pharmacoeconomics. A 2025 comparative analysis of sunitinib therapy in gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) found that a pharmacometric-based model more accurately captured real-world toxicity trends and changes in drug exposure over time compared to traditional time-to-event and Markov models used in cost-utility analyses [36]. The traditional models excessively forecasted the percentage of patients with subtherapeutic concentrations (98.7% at cycle 16 vs. 34.1% predicted by the pharmacometric model) [36].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol for Traditional PopPK Model Building

The following workflow, used by expert modelers, was detailed in a 2025 study on automation and served as the benchmark for comparison [33] [8].

- Base Model Development: Begin with a one-compartment model with first-order absorption and elimination. Estimate population parameters (fixed effects), inter-individual variability (random effects), and residual error.

- Model Progression: Sequentially test a two-compartment model, then different absorption models (e.g., zero-order, sequential zero-first-order, transit compartments).

- Covariate Model Building: Incorporate patient demographics (e.g., body weight, age, organ function) and other covariates into the model. Use stepwise forward addition and backward elimination based on statistical significance (e.g., change in OFV).

- Model Evaluation: Assess the final model using diagnostic plots, visual predictive checks, and bootstrap analysis to ensure robustness and predictive performance.

Protocol for a Hybrid ML-PBPK Analysis

A 2025 study provided a detailed protocol for a hybrid machine learning and PBPK analysis, which can be used for early human PK prediction [34].

- Data Curation and Digitization: Compile a large dataset of small molecules' physicochemical and PK properties from public sources like ChEMBL and PubChem. Digitize human plasma concentration-time profiles from literature to create a comprehensive training set.

- QSAR Model Training: For each parameter (e.g., Fu, CL, VDss, pKa), train multiple QSAR models using different ML algorithms (e.g., SVM, XGBoost) and molecular descriptors. Develop a consensus model by averaging predictions from the top-performing individual models.

- PBPK Simulation: Use the ML-predicted drug-specific parameters as inputs for a PBPK software platform. Use system-specific parameters representing human physiology.

- Validation: Compare the PBPK-simulated plasma concentration-time profiles against actual clinical data for a test set of compounds withheld from model training. Report accuracy as the percentage of predictions within 2-fold and 5-fold error ranges for AUC and Cmax.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and key decision points in the traditional PopPK model-building process.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Software

The following table lists key software tools and computational resources used in the featured experiments and the broader field of pharmacokinetic modeling.

Table 3: Key Research Tools for Pharmacokinetic Modeling

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Application | Context / Study |

|---|---|---|

| NONMEM | Industry-standard software for non-linear mixed-effects (NLME) modeling, used for PopPK model development and parameter estimation. | Used as the core estimation engine in both traditional and automated PopPK studies [33] [8]. |

| pyDarwin | A Python library containing optimization algorithms for automating the search of PopPK model structures. | Employed for global search of model space using Bayesian optimization with a random forest surrogate [33] [8]. |

| PBPK Software | Software platforms (e.g., GI-Sim, Simcyp, PK-Sim) that simulate ADME processes using physiological and drug-specific parameters. | Used in hybrid ML-PBPK frameworks to generate human PK profiles from ML-predicted parameters [34]. |

| ChEMBL / PubChem | Public databases providing extensive data on drug properties, activities, and chemical structures for training QSAR models. | Used as data sources for curating large datasets of physicochemical and PK properties [34]. |

| Tofts Model | A specific, widely-used pharmacokinetic model for analyzing Dynamic Contrast-Enhanced MRI (DCE-MRI) data to estimate tissue permeability (Ktrans) and extravascular volume (ve). | Implemented in specialized software like DCE@urLAB for preclinical image analysis [37]. |

| SVM / XGBoost | Machine learning algorithms used to develop quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models for predicting PC/PK parameters from chemical structures. | Among the top-performing algorithms for predicting parameters like Fu, CL, and VDss [34]. |

| Foxy-5 TFA | Foxy-5 TFA, MF:C28H43F3N6O14S2, MW:808.8 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| ZM223 hydrochloride | ZM223 hydrochloride, MF:C23H18ClF3N4O2S2, MW:539.0 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

The comparative analysis reveals that traditional pharmacokinetic modeling, centered on NLME PopPK, remains a robust, interpretable, and regulatory-accepted methodology. Its strengths lie in mechanistic plausibility and deep expert oversight. However, emerging approaches present compelling advantages. Machine Learning and Automation significantly accelerate model development, improve reproducibility, and can achieve predictive accuracy comparable to traditional methods, especially in early-stage discovery for predicting human PK parameters [34] [33] [8]. Furthermore, mechanism-based models like PBPK and detailed pharmacometric models offer superior biological fidelity, more accurately capturing real-world dynamics such as time-varying toxicity and drug exposure, which translates into better predictions for pharmacoeconomic and clinical outcomes [36].

The future of pharmacokinetic modeling does not lie in the outright replacement of one approach by another, but in their strategic integration. Hybrid frameworks that leverage the speed and pattern-recognition capabilities of ML for parameter prediction, the physiological grounding of PBPK, and the rigorous statistical framework of traditional PopPK will likely define the next generation of tools, enabling more efficient and informative drug development.

Physiologically-based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) modeling represents a fundamental shift from traditional compartmental pharmacokinetic approaches, integrating detailed physiological, biochemical, and anatomical data to predict drug behavior throughout the body. Unlike classical "top-down" pharmacokinetic methods that lack physiological specificity, PBPK modeling adopts a mechanistic "bottom-up" approach that incorporates species- and population-specific parameters to simulate drug concentrations in various tissues and organs [38]. This comparative analysis examines the construction, applications, and advantages of PBPK modeling against traditional pharmacokinetic methods, highlighting how the integration of physiological realism enhances predictive accuracy in drug development.

Conceptual Foundations: Traditional PK vs. PBPK Modeling

Traditional Compartmental Pharmacokinetic Modeling

Traditional pharmacokinetic (PK) modeling employs a "top-down" approach that reduces complex physiological systems into abstract mathematical compartments. These models typically characterize drug absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) using central and peripheral compartments without direct correspondence to anatomical structures [38]. Parameters such as C~max~ (maximum plasma concentration), T~max~ (time to reach C~max~), AUC (area under the concentration-time curve), and half-life are derived from plasma concentration data without mechanistic physiological basis [38]. While useful for describing observed data, these models have limited predictive capability for extrapolating to different populations, disease states, or dosing regimens due to their empirical nature and lack of physiological specificity.

PBPK Modeling: A Mechanistic Framework

PBPK modeling represents a paradigm shift toward mechanism-based prediction, constructing mathematical representations of the human body as interconnected physiological compartments corresponding to specific organs and tissues [39]. Each compartment is characterized by its anatomical and physiological properties, including tissue volume, blood flow rate, and tissue composition [38] [39]. The model integrates these system parameters with drug-specific physicochemical properties and biochemical processes to simulate concentration-time profiles in blood and individual tissues [38]. This mechanistic framework allows PBPK models to extrapolate predictions across populations, disease states, and dosing scenarios with greater scientific rigor than traditional approaches.

Table 1: Fundamental Differences Between Traditional PK and PBPK Modeling Approaches

| Characteristic | Traditional PK Modeling | PBPK Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Approach | Top-down, empirical | Bottom-up, mechanistic |

| Model Structure | Abstract compartments (central, peripheral) | Physiological compartments (organs, tissues) |

| Parameter Basis | Statistical fitting to plasma data | Physiological constants and drug properties |

| Tissue Concentration Predictions | Limited to plasma/blood | Multiple specific tissues and organs |

| Extrapolation Capability | Limited to similar conditions | Robust across populations, diseases, ages |

| Regulatory Acceptance | Established for PK parameter estimation | Growing acceptance for specific applications [38] |

PBPK Model Construction: Methodology and Workflow

Structural Design and Compartmentalization

The construction of a PBPK model begins with defining an appropriate anatomical structure comprising compartments representing key organs and tissues involved in drug disposition. A full PBPK model typically includes compartments for the liver, kidneys, gut, brain, lungs, heart, adipose tissue, muscle, and blood (both arterial and venous) [39] [40]. The specific compartments included depend on the drug's properties and the model's purpose, with tissues sharing similar characteristics sometimes "lumped" together to reduce complexity [39]. Each compartment is characterized by organ-specific volumes, blood flow rates, and composition data obtained from physiological literature [38].

The tissue model specification determines whether distribution is flow-limited (perfusion rate-limited) or membrane-limited (permeability rate-limited) [39]. Flow-limited models assume instantaneous equilibrium between blood and tissue, while membrane-limited models incorporate diffusion barriers using multiple subcompartments [39]. This distinction critically influences the mathematical equations governing drug transport and the parameterization requirements for accurate prediction.

Figure 1: PBPK Model Development Workflow

Mathematical Framework and Parameterization

PBPK models are constructed using mass balance differential equations that describe the rate of change of drug amount in each compartment [39] [40]. For a typical organ compartment, the general form of the distribution equation is:

dM~i~/dt = Q~i~ × (C~a~ - C~v~,~i~)

Where:

- dM~i~/dt = rate of change of drug amount in tissue i

- Q~i~ = blood flow to tissue i

- C~a~ = arterial drug concentration

- C~v~,~i~ = venous drug concentration leaving tissue i [40]

The model requires three categories of parameters:

- System-specific parameters: Species- and population-specific physiological values including organ volumes, blood flow rates, tissue composition, and protein levels [38]

- Drug-specific parameters: Physicochemical properties such as molecular weight, lipophilicity (logP/logD), pKa, solubility, and permeability [38]

- Drug-biological interaction parameters: Including fraction unbound in plasma (f~u~), tissue-plasma partition coefficients (K~p~), and metabolic clearance values [38]

These parameters are obtained from in vitro experiments, predictive algorithms, and literature sources, with refinement through in vitro-in vivo extrapolation (IVIVE) approaches [38] [41].

Figure 2: Anatomical Structure of a Full PBPK Model

Model Calibration, Validation, and Software Tools

PBPK model development follows a rigorous process involving calibration with available in vivo data and validation using independent datasets [38]. The "middle-out" approach, which integrates both "bottom-up" mechanism-based predictions and "top-down" parameter estimation from observed data, is frequently employed to address scientific knowledge gaps [38]. Model validation confirms predictive performance before application to simulation scenarios.

Specialized software platforms facilitate PBPK model construction and application:

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of PBPK Modeling Platforms

| Software | Developer | Key Features | Typical Applications | Access Type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simcyp Simulator | Certara | Extensive physiological libraries, virtual population modeling, DDI prediction | Human PK prediction, DDI assessment, pediatric/special population modeling | Commercial [38] |

| GastroPlus | Simulation Plus | Oral absorption modeling, dissolution, physiology-based biopharmaceutics | Formulation optimization, bioavailability prediction | Commercial [38] |

| PK-Sim | Open Systems Pharmacology | Whole-body PBPK modeling, open-source capabilities | Cross-species extrapolation, academic research | Open Source [38] |

Experimental Validation: Comparative Case Study in GIST Therapy

Experimental Design and Methodology

A comprehensive comparative analysis evaluated the performance of PBPK modeling against traditional pharmacoeconomic models in predicting outcomes of sunitinib therapy for gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) [36]. The study simulated a two-arm trial comparing sunitinib 37.5 mg daily versus no treatment using a pharmacometric-based PBPK framework to generate "true" clinical outcomes for 1000 virtual patients with metastatic/unresectable GIST [36]. Simulations ran over 104 weeks, incorporating realistic clinical practices including dose reductions based on adverse events.

The PBPK model framework incorporated multiple interconnected components:

- Time course models for adverse events (hypertension, neutropenia, hand-foot syndrome, fatigue, thrombocytopenia)

- Soluble Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor Receptor-3 (sVEGFR-3) concentration kinetics

- Tumor growth dynamics

- Overall survival (Weibull time-to-event model) [36]

Traditional modeling approaches included time-to-event (exponential and Weibull) and Markov (discrete and continuous) models with logistic regression for adverse events [36]. All models were compared against the PBPK-generated "truth" for accuracy in predicting clinical outcomes and cost-utility ratios.

Comparative Performance Results

The PBPK framework demonstrated superior performance in capturing dynamic toxicity patterns and drug exposure changes compared to traditional models:

Table 3: Comparative Performance of Modeling Approaches in Sunitinib GIST Therapy

| Model Framework | Cost-Utility Prediction | Deviation from PBPK Result | Toxicity Pattern Accuracy | Drug Exposure Prediction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PBPK (Reference) | 142,756 €/QALY | Baseline | Captured dynamic changes (e.g., HFS incidence peak at cycle 4) | Accurate (13.7% to 34.1% subtherapeutic) |

| Discrete Markov | 112,483 €/QALY | -21.2% | Stable incidence over all cycles | Overestimated (24.6% to 98.7% subtherapeutic) |

| Continuous Markov | 121,215 €/QALY | -15.1% | Stable incidence over all cycles | Overestimated (24.6% to 98.7% subtherapeutic) |

| TTE Weibull | 152,980 €/QALY | +7.2% | Stable incidence over all cycles | Overestimated (24.6% to 98.7% subtherapeutic) |

| TTE Exponential | 199,282 €/QALY | +39.6% | Stable incidence over all cycles | Overestimated (24.6% to 98.7% subtherapeutic) |

The PBPK model accurately represented the increase in hand-foot syndrome incidence until cycle 4 followed by a decrease, while traditional models showed stable incidence across all treatment cycles [36]. Additionally, traditional models excessively forecasted the percentage of patients experiencing subtherapeutic sunitinib concentrations over time compared to the PBPK framework [36].

Successful PBPK model construction requires specialized tools and resources across multiple domains:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for PBPK Modeling

| Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Function in PBPK Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Software Platforms | Simcyp, GastroPlus, PK-Sim, NONMEM, Phoenix WinNonlin | Model construction, simulation, parameter estimation, and data analysis [38] |

| Physiological Databases | ICRP publications, Brown et al. species-specific data | Source of physiological parameters (organ volumes, blood flows, tissue composition) [39] |

| In Vitro Assay Systems | Caco-2 permeability assays, metabolic stability assays, plasma protein binding assays | Generation of drug-specific parameters for model input [38] |

| Predictive Algorithms | Poulin & Theil, Rodgers & Rowland, Schmitt methods | Estimation of tissue:plasma partition coefficients from physicochemical properties [39] |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Platforms | Liver, intestine, kidney, multi-organ chips | Validation of model predictions using engineered human tissues [42] |

PBPK modeling represents a transformative approach that integrates physiology, biochemistry, and anatomy to overcome limitations of traditional pharmacokinetic methods. The mechanistic foundation of PBPK models provides superior predictive capability for drug behavior across diverse populations and conditions, as demonstrated in the sunitinib case study where the PBPK framework more accurately captured toxicity dynamics and drug exposure patterns [36]. While requiring more extensive parameterization and specialized expertise, PBPK modeling offers enhanced scientific rigor for drug development decisions, particularly for special populations, drug-drug interactions, and formulation optimization [38]. As these modeling approaches continue to evolve through integration with emerging technologies like organ-on-a-chip platforms and machine learning, they promise to further transform pharmacokinetic prediction and personalized therapy optimization [42].

Pharmacokinetic/Pharmacodynamic (PK/PD) modeling represents a critical discipline in clinical pharmacology that quantitatively integrates pharmacokinetics (what the body does to a drug) with pharmacological systems and pathophysiological processes to understand the intensity and time-course of drug effects on the body [43]. These mathematical models characterize the temporal aspects of drug effects by emulating mechanisms of action, allowing for the quantification and prediction of drug-system interactions for both therapeutic and adverse drug responses [43]. The field has evolved significantly from traditional empirical approaches toward more sophisticated mechanism-based models that offer greater predictive power and biological relevance.