Validating Analytical Methods for Drug Stability: A Guide to ICH Q2(R2) and the 2025 Q1 Framework

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating analytical methods for drug stability testing within the modern ICH regulatory landscape.

Validating Analytical Methods for Drug Stability: A Guide to ICH Q2(R2) and the 2025 Q1 Framework

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating analytical methods for drug stability testing within the modern ICH regulatory landscape. It covers the foundational principles of the newly consolidated ICH Q1 (2025 Draft) guideline and the updated ICH Q2(R2) on analytical method validation. The scope extends from core concepts and methodological applications to troubleshooting common challenges and implementing a lifecycle approach for robust, compliant stability programs, including advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) and complex biologics.

The New Foundation: Understanding the 2025 ICH Q1 Consolidation and Its Impact on Analytical Validation

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) has undertaken a monumental step to modernize and consolidate the foundational guidelines governing the stability testing of pharmaceuticals. The new ICH Q1 Draft Guideline, which reached Step 2b of the ICH process in April 2025, represents a comprehensive revision that unifies the previously fragmented ICH Q1A-F and Q5C guidelines into a single, cohesive document [1] [2] [3]. This consolidation marks a significant shift from a series of documents developed incrementally since 1993 to a modernized, unified framework that reflects current scientific and regulatory practices [3]. The draft guideline outlines stability data expectations for drug substances and drug products, providing evidence on how their quality varies over time under the influence of environmental factors like temperature, humidity, and light [1].

The revision aims to address the evolving landscape of pharmaceutical development, which now includes complex biological products and advanced therapies that were not adequately covered in the original guidelines [4]. By promoting a more consistent, science- and risk-based approach to stability testing, the ICH seeks to harmonize regulatory expectations across global markets and provide a clearer, more adaptable framework that supports efficient drug development and robust product quality throughout the lifecycle [2] [3]. This article examines how the 2025 draft replaces the previous collection of guidelines, the implications for analytical method validation, and the new opportunities it presents for researchers and drug development professionals.

From Multiple Documents to One: The Scope of unification

The 2025 ICH Q1 draft guideline represents a significant consolidation of seven previously separate stability guidelines into a single comprehensive document. This unification simplifies the regulatory landscape for pharmaceutical scientists and establishes a coherent framework for stability testing across diverse product types.

The Pre-2025 Fragmented Landscape

Before this consolidation, stability testing requirements were spread across multiple documents, each addressing specific aspects:

- ICH Q1A(R2): Provided the core stability data package for new drug substances and products [5] [4].

- ICH Q1B: Focused specifically on photostability testing requirements [4].

- ICH Q1C: Addressed stability testing for new dosage forms [4].

- ICH Q1D: Covered bracketing and matrixing designs to reduce stability testing burden [4].

- ICH Q1E: Offered guidance on evaluation of stability data [4].

- ICH Q1F: Provided stability data requirements for new regions (now withdrawn) [2].

- ICH Q5C: Covered stability testing of biotechnological/biological products [4] [3].

This fragmented approach often led to challenges in interpretation and implementation, particularly for complex products that fell under multiple guidelines simultaneously [3].

The Unified 2025 Framework

The new draft guideline supersedes all aforementioned documents, creating a single source for stability testing requirements [1] [4]. The consolidated structure comprises 18 main sections and 3 annexes, organized to address both foundational stability principles and specialized needs of emerging product types [3]. This modular approach allows for more consistent application across synthetic molecules, biologics, and advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs) [2] [6].

Table: Direct Replacement Mapping of ICH Guidelines

| Previous Guideline | Primary Focus | Status in 2025 Draft |

|---|---|---|

| ICH Q1A(R2) | Stability testing of new drug substances & products | Fully incorporated and expanded |

| ICH Q1B | Photostability testing | Integrated into main document |

| ICH Q1C | Stability testing for new dosage forms | Incorporated with expanded scope |

| ICH Q1D | Bracketing and matrixing designs | Enhanced and included as Annex 1 |

| ICH Q1E | Evaluation of stability data | Integrated with new statistical guidance |

| ICH Q1F | Stability data for new regions | Withdrawn; global zones now included |

| ICH Q5C | Stability of biotechnological products | Fully integrated into main framework |

The unification specifically extends the scope to include synthetic and biological drug substances and products, including vaccines, gene therapies, and combination products that were not comprehensively covered under the existing stability guidances [4] [6]. This is particularly significant for developers of advanced therapies, who previously had to navigate multiple documents with potential gaps for their innovative products [3].

Key Changes and Implications for Analytical Method Validation

The 2025 ICH Q1 draft introduces substantial changes that directly impact how analytical methods for stability testing are developed, validated, and implemented throughout the product lifecycle. These changes reflect a modernized scientific approach that emphasizes risk-based principles and methodological robustness.

Expanded Scope and Lifecycle Management

The draft guideline significantly broadens its applicability to include product categories such as advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), vaccines, and other complex biological products including combination products [4] [2]. This expansion necessitates development of novel analytical methods capable of addressing the unique stability challenges presented by these advanced modalities, which may include cell viability assays for ATMPs or specialized potency assays for gene therapies [3].

Furthermore, the guideline introduces lifecycle stability management aligned with ICH Q12, encouraging a more proactive, ongoing stability planning throughout the product lifecycle [2] [3]. This represents a shift from stability as a box-ticking exercise for regulatory submission to an integrated component of pharmaceutical quality systems [3]. For analytical method validation, this means methods must be robust and adaptable enough to support continued verification throughout the product's market life, including post-approval changes.

Enhanced Statistical Modeling and Data Analysis

The draft provides clearer instructions on using statistical models for stability testing, replacing previous standards that were often perceived as vague and complicated [3]. This includes enhanced guidance on stability modeling and more precise requirements for statistical data analysis and extrapolation when establishing re-test periods or shelf life [2].

For analytical scientists, this emphasizes the need for statistically sound method validation approaches that generate data suitable for sophisticated stability modeling. The methods must produce reliable, precise data that can support the statistical models used to predict product stability under various conditions [3]. The draft also formally acknowledges the role of reduced stability studies using tools like bracketing, matrixing, and modeling, provided they are supported by adequate scientific justification and robust analytical data [3].

Risk-Based and Science-Driven Approaches

The new guideline strongly emphasizes the application of science- and risk-based principles throughout stability testing programs [1] [2]. This aligns with modern Quality-by-Design and lifecycle management principles, offering greater flexibility while maintaining regulatory confidence [3].

This approach requires analytical methods to be developed with a comprehensive understanding of critical quality attributes and their potential variation under stability testing conditions. Method validation should demonstrate the method's ability to detect meaningful changes in these attributes, with validation parameters tailored based on risk assessment [3]. The draft encourages leaner stability study designs but increases the burden for scientific justification, requiring more comprehensive data and documentation to support any reduced testing protocols [3].

Practical Implementation: Protocols, Materials, and Workflows

Implementing the new ICH Q1 guideline requires understanding updated experimental approaches and their implications for daily laboratory practice. This section provides practical guidance on methodologies, essential materials, and analytical workflows aligned with the new framework.

Research Reagent Solutions for Stability Testing

Stability testing according to ICH Q1 requires specific reagents and materials to ensure accurate, reproducible results. The following table details essential solutions and their functions in stability studies.

Table: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Stability Testing

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function in Stability Testing | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Quantification of active ingredient and degradation products; system suitability [3] | Must be well-characterized and stored under validated conditions |

| Forced Degradation Solutions | Elucidating degradation pathways and validating stability-indicating methods [7] | Include acid, base, oxidative, thermal, and photolytic stress conditions |

| Mobile Phase Components | Chromatographic separation of analytes and degradation products [7] | pH, buffer concentration, and organic modifier must be robust |

| Microbiological Media | Microbial limit testing and sterility testing for parenteral products [7] | Growth promotion testing must meet pharmacopeial requirements |

| Preservative Efficacy Testing Materials | Evaluating antimicrobial effectiveness in multidose products [7] | Challenge organisms must represent likely contaminants |

Updated Stability Testing Workflow

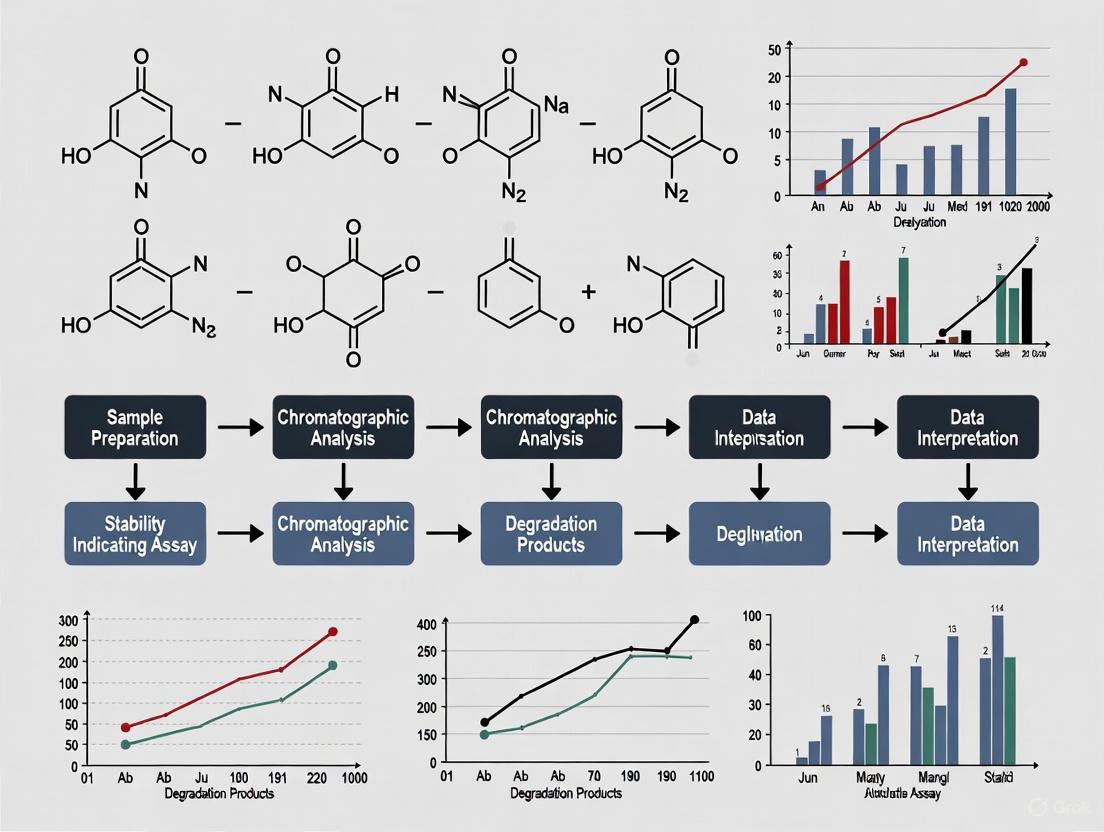

The new ICH Q1 guideline formalizes a comprehensive approach to stability testing that integrates quality by design and risk management principles. The following workflow diagram illustrates the key stages in designing and conducting stability studies under the updated framework.

Experimental Protocols for Key Stability Studies

The experimental methodologies for stability testing have been refined in the new guideline, with particular emphasis on scientific justification and risk-based approaches.

Long-Term Stability Testing Protocol

Long-term testing remains the cornerstone of stability programs, with the draft guideline reinforcing its importance while allowing for more flexible, risk-based designs [7].

- Objective: Evaluate drug substance/product quality under recommended storage conditions to establish shelf life or re-test period [7].

- Storage Conditions: 25°C ± 2°C / 60% RH ± 5% RH or 30°C ± 2°C / 65% RH ± 5% RH, depending on climatic zone [7].

- Testing Frequency: Every 3 months during first year, every 6 months during second year, and annually thereafter for drugs with proposed shelf life of at least 12 months [7].

- Key Analytical Parameters: Appearance, assay, degradation products, dissolution (for solids), moisture content, and microbiological testing where applicable [7].

- Statistical Analysis: Employment of stability modeling and statistical analysis for shelf life estimation, with clearer guidance provided in the new draft [2] [3].

Accelerated Stability Testing Protocol

Accelerated studies continue to play a crucial role in predicting long-term stability and identifying potential stability issues [7].

- Objective: Predict long-term stability over a shorter period and identify potential stability issues that may occur during storage and transport [7].

- Storage Conditions: 40°C ± 2°C / 75% RH ± 5% RH for minimum of 6 months [7].

- Testing Frequency: Typically at 0, 1, 2, 3, and 6-month timepoints [7].

- Key Analytical Parameters: Same as long-term testing, with particular attention to degradation products that may form more rapidly under stress conditions [7].

- Data Interpretation: Results from accelerated studies inform the design of long-term studies and may support extrapolation of shelf life when supported by statistical analysis [3].

Stability Testing for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs)

The new guideline includes specific, though limited, guidance for ATMPs, addressing a significant gap in the previous guidelines [3].

- Special Considerations: Account for unique stability challenges of cell and gene therapies, including viability, potency, and unique degradation pathways [3].

- Storage Conditions: Often require cryogenic conditions or specific temperature ranges not covered by standard climatic zones [3].

- Testing Parameters: Include product-specific quality attributes such as cell viability, identity, purity, and potency markers [3].

- In-Use Stability: Critical for products requiring thawing, dilution, or other manipulation before administration [3].

Comparative Analysis: Previous vs. New Framework

The transition from the previous collection of guidelines to the unified 2025 draft represents a fundamental shift in stability testing philosophy and practice. This section provides a detailed comparison of key aspects across both frameworks.

Table: Comprehensive Comparison of Previous vs. New ICH Q1 Framework

| Aspect | Previous Framework (Q1A-F + Q5C) | New 2025 Draft Framework | Impact on Analytical Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Document Structure | 7 separate guidelines with some overlapping and gaps [3] | Single unified document with 18 sections + 3 annexes [3] | Simplified reference; clearer requirements |

| Product Scope | Primarily synthetic drugs & some biologics [4] | Includes ATMPs, vaccines, combination products [4] [2] | New methods needed for novel modalities |

| Statistical Guidance | Vague and complicated standards [3] | Clear instructions on modeling and data analysis [2] [3] | More robust method validation required |

| Study Design Approach | Largely fixed designs with limited flexibility [3] | Science- and risk-based with reduced studies allowed [1] [3] | Higher burden for scientific justification |

| Lifecycle Management | Focused on registration requirements [5] | Integrated with ICH Q12 for full lifecycle [2] [6] | Methods must support post-approval changes |

| Climatic Zones Coverage | Limited to specific ICH regions [7] | Includes all zones for global harmonization [6] | Broader environmental validation needed |

| Reference Standards | Limited specific guidance [3] | Clearer instructions on testing and storage [3] | Improved standardization across methods |

Regulatory and Implementation Timeline

Understanding the implementation status of the new guideline is crucial for planning stability programs. The following diagram illustrates the development timeline and future milestones for the ICH Q1 draft guideline.

The 2025 ICH Q1 draft guideline represents a transformative shift from a fragmented collection of stability guidelines to a unified, modern framework that addresses the current and future needs of the pharmaceutical industry. By consolidating Q1A-F and Q5C into a single document, the draft provides a more coherent approach to stability testing while expanding coverage to include advanced therapies, implementing enhanced statistical guidance, and promoting science- and risk-based principles [1] [2] [3].

For researchers and drug development professionals, this consolidation means simplified referencing and more consistent expectations across different product types. However, it also brings new responsibilities in justifying stability strategies through robust scientific data and comprehensive risk assessment [3]. The emphasis on lifecycle management aligns stability testing with broader quality systems, requiring analytical methods to be validated for long-term use across the product's commercial life [2] [6].

As the guideline progresses toward final implementation, stakeholders should proactively prepare by reviewing the draft document, assessing its impact on current programs, updating training curricula, and exploring digital tools that support the enhanced modeling and statistical analysis requirements [3]. While the full implementation timeline remains ahead, early engagement with the new framework will position organizations to successfully navigate this significant evolution in stability testing requirements, ultimately supporting the development of safe, effective, and high-quality medicines for global markets.

The stability testing landscape for pharmaceuticals is undergoing its most significant transformation in over two decades. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) has consolidated its previously fragmented stability guidances (Q1A-F and Q5C) into a single, comprehensive document—the draft ICH Q1 guideline released in 2025 [8] [9] [4]. This overhaul represents more than mere administrative consolidation; it fundamentally modernizes stability requirements to accommodate advanced therapeutic modalities that did not exist when the original guidances were written. For researchers and drug development professionals, this expansion explicitly brings Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs), complex biologics, and combination products under a harmonized stability framework for the first time, addressing critical gaps that have long challenged developers of innovative therapies [8] [9].

This guide compares the new stability testing paradigm against previous requirements, with particular focus on product categories that previously lacked clear ICH direction. We examine the experimental approaches and analytical method validation strategies needed to comply with the modernized, science-driven framework that emphasizes risk-based principles and lifecycle management [9].

Comparative Analysis of Old vs. New Stability Guidance

Table: Comparison of Key Changes in ICH Stability Guidance

| Aspect | Previous Approach (ICH Q1A-F, Q5C) | New Consolidated Approach (ICH Q1 2025 Draft) |

|---|---|---|

| Document Structure | Fragmented across multiple documents (Q1A-R2, Q1B, Q1C, Q1D, Q1E, Q5C) [8] | Single comprehensive guideline (18 sections + 3 annexes) [9] |

| Product Scope | Primarily small molecules; some biologics under Q5C [8] | Explicit inclusion of ATMPs, vaccines, oligonucleotides, peptides, combination products [8] [9] |

| Philosophical Basis | Standardized, "one-size-fits-all" protocols [8] | Science- and risk-based approaches with "alternative, scientifically justified approaches" [9] |

| Stability Strategy | Fixed study designs | Encourages bracketing, matrixing, predictive modeling with justification [8] |

| Lifecycle Perspective | Focused primarily on pre-approval data [8] | Formalized stability lifecycle management continuing post-approval [8] [9] |

| Statistical Guidance | Limited statistical evaluation guidance [8] | New annex dedicated to stability modeling and statistical evaluations [9] |

Experimental Protocols for New Product Categories

Stability Study Design for Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs)

ATMPs present unique stability challenges due to their living cellular components, complex biological activities, and frequently cryopreserved storage requirements [10]. The new ICH Q1 draft includes Annex 3, which provides specific stability guidance for these products [9].

Critical Methodology Considerations:

- Potency Assay Validation: Employ orthogonal methods using different scientific principles to measure the same critical quality attribute (CQA). For cell-based therapies, this includes both functional assays and viability measurements [11].

- Real-Time Stability Protocols: Design studies that monitor critical quality attributes throughout the proposed shelf life. For cryopreserved products, this includes stability through multiple freeze-thaw cycles [10].

- Container Closure System Testing: Verify compatibility with final container systems, including potential interactions with cryopreservatives and storage bags [9].

- In-Use Stability Assessments: Evaluate stability under conditions of actual clinical use, including post-thaw hold times and administration periods [9].

Stability Testing for Complex Biological Products

The expanded guidance explicitly addresses stability considerations for vaccines, oligonucleotides, peptides, and plasma-derived products [9].

Key Experimental Approaches:

- Forced Degradation Studies: Conduct under more severe conditions than accelerated testing to identify potential degradation pathways and develop stability-indicating methods [9].

- Multi-Parameter Stability Assessment: Monitor biological activity, conformational integrity, and particulate formation in addition to traditional chemical and physical parameters [9].

- Adjuvant and Excipient Stability: For vaccines and formulated biologics, include novel excipients and adjuvants in stability protocols due to their potential impact on product quality [9].

Combination Product Stability Considerations

For drug-device combination products, the guidance requires integrated stability approaches that account for both pharmaceutical and device components [9].

Essential Protocol Elements:

- Functionality Testing: Include device performance metrics throughout stability studies to ensure proper operation at expiry [9].

- Interface Assessment: Evaluate chemical and physical interactions between drug and device components over time [9].

- Simulated-Use Testing: Incorporate testing that mimics patient use conditions at various timepoints throughout the shelf life [9].

Analytical Method Validation in Stability Testing

Phase-Appropriate Validation Requirements

The regulatory approach to analytical method validation has evolved to reflect a phase-appropriate framework while maintaining scientific rigor [11].

Table: Analytical Method Expectations Across Development Phases

| Development Phase | Method Validation Expectation | Stability Testing Application |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1 | Assay qualification (reliable, reproducible, sensitive enough for safety decisions) [11] | Monitoring of critical safety attributes (sterility, purity, identity) |

| Phase 2 | Refinement of critical process parameters; beginning of phase-appropriate validation [11] | Expanded stability testing with tighter specifications |

| Phase 3 to Commercial | Full validation per ICH Q2(R2) [12] [11] | Comprehensive stability-indicating methods for shelf-life determination |

Orthogonal Method Implementation

Regulators increasingly expect orthogonal methods—employing different scientific principles to measure the same attribute—particularly for critical quality attributes of complex products [11].

Implementation Framework:

- Justification Strategy: Provide scientific rationale for each orthogonal method selected, explaining how different measurement principles collectively ensure result reliability [11].

- Method Comparison Protocols: Establish correlation between different methods during development phase to demonstrate complementary value [11].

- Phase-Appropriate Implementation: Introduce orthogonal methods early in development, with increasing rigor through commercialization [11].

Visualization: Modern Stability Strategy Development

Modern Stability Strategy Development Flow

This workflow illustrates the science- and risk-based approach endorsed by the modernized ICH Q1 guideline. The process begins with thorough product understanding, proceeds through risk assessment, and implements flexible, justified stability strategies with ongoing lifecycle management [9].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Key Reagents for Advanced Stability Programs

| Reagent/Category | Function in Stability Testing | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Standards | Quantification and method qualification | Must be fully qualified; characterized for CQAs [11] |

| Cell-Based Assay Systems | Potency determination for biologics and ATMPs | Functional, biologically relevant assays required by regulators [11] |

| GMP-Grade Culture Media | ATMP manufacturing and stability assessment | Essential for maintaining cell viability and function [10] [11] |

| Molecular Characterization Tools | Genetic stability assessment for ATMPs | Karyotype analysis to detect genetic instability [10] |

| Orthogonal Detection Reagents | Multiple method implementation for CQAs | Different scientific principles for same attribute [11] |

The consolidated ICH Q1 guideline represents a paradigm shift in stability testing, moving from rigid, standardized protocols to flexible, science-driven strategies. This expansion to include ATMPs, complex biologics, and combination products addresses longstanding gaps in regulatory guidance while creating new considerations for drug developers [8] [9].

Successful implementation requires:

- Early engagement with regulatory agencies through INTERACT or pre-IND meetings for complex products [11]

- Development of orthogonal analytical methods for critical quality attributes [11]

- Comprehensive risk assessment to justify reduced designs or modeling approaches [9]

- Lifecycle planning for stability monitoring beyond initial approval [8]

The modernized stability framework offers opportunities for more efficient, scientifically grounded stability programs while demanding greater expertise and justification from sponsors. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding these expanded requirements is essential for successfully navigating the approval pathway for advanced therapies.

The recent publication of the draft ICH Q1 guideline, a consolidated revision superseding the ICH Q1A-F and Q5C series, marks a significant evolution in global stability testing requirements for pharmaceuticals [1] [13]. This updated framework expands its scope to encompass a broader range of product types, including advanced therapy medicinal products (ATMPs), vaccines, and other complex biologicals, while emphasizing science- and risk-based principles [14] [2]. Within this modernized context, the role of thoroughly validated analytical methods becomes more critical than ever. They form the foundational backbone that generates the reliable, reproducible stability data upon which all subsequent decisions—from shelf-life estimation to regulatory approval—depend.

This guide examines the integral connection between the new ICH Q1 framework and validated stability-indicating methods, providing a direct comparison of traditional versus modernized approaches. We will explore the experimental protocols that underpin method validation and demonstrate how these methodologies ensure data integrity throughout the product lifecycle.

The New ICH Q1 Framework: A Consolidated Foundation for Modern Products

The ICH Q1 draft guideline, reaching Step 2 of the ICH process in April 2025, represents a comprehensive effort to harmonize and modernize global stability testing practices [14] [2]. Its core objective is to provide harmonized requirements for generating stability data that supports regulatory submissions and post-approval changes across a diverse spectrum of drug substances and products [13].

Key Updates and Expanded Scope

The revised guideline is structured into 18 sections and three annexes, covering everything from development stability studies to lifecycle considerations [14]. A primary update is the expansion of product coverage, moving beyond traditional synthetic chemicals to include:

- Synthetic chemical entities, including oligonucleotides and semi-synthetics

- Biologicals, such as therapeutic proteins and plasma-derived products

- Advanced Therapy Medicinal Products (ATMPs) like cell and gene therapies (e.g., CAR-T cells)

- Vaccines and adjuvants

- Combination drug-device products [14] [2]

This consolidation also introduces new content on in-use studies, short-term stability, stability modeling, and guidance for product lifecycle management aligned with ICH Q12 [14] [2]. The guideline emphasizes that stability studies must provide evidence on how the quality of a drug substance or product varies over time under the influence of environmental factors like temperature, humidity, and light [1].

Stability Testing Conditions in the New Framework

The following table summarizes the core storage conditions for stability testing as outlined in the ICH guidelines, which are designed to simulate the climatic zones where products will be marketed.

Table 1: Standard ICH Stability Testing Conditions for Climatic Zones I and II

| Study Type | Storage Conditions | Minimum Time Period | Primary Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long-Term | 25°C ± 2°C / 60% RH ± 5% RH or 30°C ± 2°C / 65% RH ± 5% RH | 12 months | Primary data source for re-test period/shelf life [15] |

| Intermediate | 30°C ± 2°C / 65% RH ± 5% RH | 6 months | Bridges long-term and accelerated data [15] |

| Accelerated | 40°C ± 2°C / 75% RH ± 5% RH | 6 months | Evaluates short-term, extreme condition effects [15] |

The Indispensable Role of Validated Analytical Methods

Within the structure of ICH Q1, validated analytical methods are not merely a technical requirement but the critical component that ensures the integrity of the entire stability assessment. As defined by regulatory requirements, "The accuracy, sensitivity, specificity, and reproducibility of test methods employed by the firm shall be established and documented" [16]. Method validation is the process of demonstrating that an analytical procedure is suitable for its intended purpose, confirming it can execute reliably and reproducibly to generate accurate data for monitoring drug substance and product quality [16].

The Stability-Indicating Method: A Core Concept

A stability-indicating method is an analytical procedure that can accurately and reliably measure the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and its degradation products without interference [16]. The core requirement is that the method must physically separate (baseline-resolve) the API, process impurities, and degradation products above the reporting thresholds [16]. This is typically achieved through forced degradation studies during method development, which investigate the main degradative pathways of the drug substance and product. These studies provide samples with sufficient degradation products to evaluate the method's ability to separate and quantify all relevant analytes, thereby demonstrating its specificity [16].

Comparative Analysis: The Impact of Method Validation on Stability Data Quality

The quality of stability data generated under ICH Q1 is directly contingent upon the rigor of the analytical method validation. The table below contrasts the outcomes of stability studies supported by poorly characterized methods versus those backed by fully validated, stability-indicating methods.

Table 2: Comparison of Stability Study Outcomes Based on Analytical Method Robustness

| Aspect | Poorly Characterized Methods | Validated Stability-Indicating Methods |

|---|---|---|

| Data Reliability | Questionable; potential for inaccurate potency and impurity results [16] | High; results are accurate, reproducible, and reliable for decision-making [16] |

| Degradation Detection | May miss critical degradants or misidentify peaks [16] | Comprehensively identifies and quantifies degradants through forced degradation studies [16] |

| Shelf-Life Estimation | Risky; based on potentially incomplete data, risking patient safety and product quality [15] | Scientifically sound; supports justified and accurate shelf-life claims using statistical evaluation [14] |

| Regulatory Compliance | Low; fails to meet ICH Q2, USP <1225>, and GMP requirements [16] | High; meets all regulatory validation requirements for submissions like NDAs [16] |

| Lifecycle Management | Difficult to manage post-approval changes due to unreliable baseline [16] | Enables effective lifecycle management and support for post-approval changes (per ICH Q12) [2] |

Core Validation Parameters and Experimental Protocols

The validation of a stability-indicating HPLC method is a systematic process governed by protocols with pre-defined acceptance criteria. The following section details the key parameters and methodologies involved.

Method Validation Parameters and Their Definitions

The validation of a stability-indicating method involves assessing multiple inter-related parameters to ensure its overall suitability.

Figure 1: The core parameters required for validating a stability-indicating analytical method, demonstrating their relationship to the overall method's purpose [16].

Detailed Experimental Protocols for Key Parameters

Specificity

- Objective: To demonstrate the method's ability to unequivocally assess the analyte in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradants, or excipients [16].

- Protocol:

- Forced Degradation Studies: Expose the drug substance and product to stress conditions (e.g., acid, base, oxidation, heat, and light) to generate degradation products [16].

- Chromatographic Separation: Inject stressed samples and demonstrate that the analyte peak is free from interference and that all degradation products are baseline-resolved [16].

- Peak Purity Assessment: Use a photodiode array (PDA) detector or mass spectrometry (MS) to confirm the homogeneity of the API peak, proving that no co-eluting impurities are present [16].

Accuracy

- Objective: To establish the closeness of agreement between the value found and the value accepted as a true or reference value [16].

- Protocol:

- Spiked Recovery Experiments: For a drug product, prepare a placebo blank and spike it with known quantities of the API (and available impurities) at multiple concentration levels, typically 80%, 100%, and 120% of the target assay concentration [16].

- Replication: Perform a minimum of nine determinations over the three concentration levels (e.g., three preparations at each level) [16].

- Calculation: Calculate the percent recovery of the analyte. Acceptance criteria are often set, for example, at 98.0–102.0% recovery for the API at the 100% level [16].

Precision

- Objective: To demonstrate the degree of scatter between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample [16].

- Protocol:

- Repeatability: Inject a minimum of five replicates of a homogeneous standard or sample preparation by one analyst on the same day. System precision (injection repeatability) is often required to have an RSD < 2.0% for peak areas [16].

- Intermediate Precision: Have a second analyst on a different day using different equipment repeat the assay of a homogeneous sample batch. The combined data from both analysts should meet pre-set criteria (e.g., overall RSD < 2.0%) [16].

Table 3: The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials for Method Validation

| Reagent / Material | Critical Function in Validation |

|---|---|

| Drug Substance (API) Reference Standard | Serves as the primary benchmark for identity, potency, and purity assessments [16]. |

| Known Impurity & Degradation Standards | Used to confirm method specificity, establish relative response factors, and validate accuracy for impurities [16]. |

| Placebo Formulation (for Drug Product) | A mock drug product without API; critical for demonstrating specificity and accuracy free from excipient interference [16]. |

| Forced Degradation Reagents | Acids, bases, oxidants, etc., used to intentionally degrade the product and challenge the method's stability-indicating properties [16]. |

| Mass Spectrometry-Compatible Solvents | Enable the use of MS as an orthogonal detection technique for peak identification and purity confirmation during method development [16]. |

The updated ICH Q1 guideline provides a modernized, harmonized framework for stability testing, but its effectiveness is entirely dependent on the quality of the analytical data fed into it. Validated, stability-indicating methods are not a peripheral compliance activity; they are the critical backbone that ensures the reliability of stability data for shelf-life prediction, supports regulatory submissions across a widening array of complex products, and ultimately safeguards patient safety. As the industry moves toward greater adoption of risk-based approaches, stability modeling, and lifecycle management, the demand for robust, well-understood analytical procedures will only intensify. The successful implementation of the new Q1 framework, therefore, hinges on a continued commitment to rigorous analytical method validation.

In the landscape of global pharmaceutical development, the International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines Q8, Q9, and Q10 represent a fundamental shift from traditional, quality-by-testing approaches toward a modern, integrated framework built on science-based and risk-based principles [17]. These guidelines form a synergistic system that guides the entire product lifecycle, from initial development through commercial manufacturing, with the ultimate goal of robustly ensuring product quality, safety, and efficacy [18] [19]. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) emphasizes that these guidelines should be viewed as an integrated system, with each providing specific details to support product realization and a lifecycle that remains in a state of control [20].

This triad of guidelines can be visualized as a three-legged stool, where each leg is essential for stability [21]. ICH Q8 (Pharmaceutical Development) introduces the systematic methodology of Quality by Design (QbD), ensuring that quality is built into the product from the outset. ICH Q9 (Quality Risk Management) provides the tools and principles for a proactive approach to identifying and controlling potential risks to quality. ICH Q10 (Pharmaceutical Quality System) establishes a comprehensive management framework that enshrines these concepts and drives continual improvement [17] [18]. Together, they enable the industry to achieve a more "maximally efficient, agile, [and] flexible pharmaceutical manufacturing sector that reliably produces high quality drug products" [21].

Comparative Analysis of ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10 Guidelines

While functionally interdependent, each ICH guideline possesses a distinct scope, primary objective, and set of core elements. Their complementary roles form the backbone of a modern pharmaceutical quality system.

Table 1: Core Components and Functions of the ICH Q8-Q10 Guidelines

| Guideline | Primary Focus & Objective | Key Concepts & Elements | Contribution to the Integrated System |

|---|---|---|---|

| ICH Q8 (R2): Pharmaceutical Development [17] [22] [21] | Focus: Pharmaceutical development process.Objective: To ensure systematic design and development of drug products and processes to consistently deliver intended performance. | • Quality by Design (QbD)• Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP)• Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)• Critical Process Parameters (CPPs)• Design Space• Control Strategy | Provides the scientific foundation and road map (QTPP, CQAs) for development. Establishes a proactive framework (QbD) for building in quality, rather than testing it in. |

| ICH Q9 (R1): Quality Risk Management [17] [22] | Focus: Risk management principles and tools.Objective: To provide a proactive framework for identifying, assessing, controlling, communicating, and reviewing risks to quality. | • Risk Assessment (Identification, Analysis, Evaluation)• Risk Control (Reduction, Acceptance)• Risk Communication & Review• Risk Management Tools (e.g., FMEA, HACCP) | Provides the decision-making framework. Enables science-based decisions by ensuring the level of effort and control is commensurate with the level of risk to the patient. |

| ICH Q10: Pharmaceutical Quality System [17] [18] | Focus: Comprehensive quality management system.Objective: To establish a robust system for managing quality across the product lifecycle, enabling continual improvement. | • Process Performance & Product Quality Monitoring• Corrective and Preventive Action (CAPA) System• Change Management System• Management Review• Knowledge Management | Provides the operational infrastructure and culture. Ensures QbD and QRM principles are effectively implemented, monitored, and improved upon throughout the product's life. |

The Integrated Workflow: From Concept to Commercial Product

The power of ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10 is fully realized when their principles are woven into a single, seamless workflow from product conception to commercial manufacturing and beyond. The following diagram illustrates this integrated, lifecycle approach.

The workflow begins with ICH Q8, where the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) is defined as a prospective summary of the drug's desired quality characteristics [21]. This leads to the identification of Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs)—the physical, chemical, biological, or microbiological properties that must be controlled to ensure product quality [22] [21].

ICH Q9's risk management principles are then applied to link Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) and Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) to the CQAs [19]. This risk assessment is foundational for developing a control strategy to ensure that CQAs are consistently met [20]. The knowledge gained feeds back into Q8 to establish the manufacturing process and its associated design space—the multidimensional combination of variables demonstrated to assure quality [22].

Finally, ICH Q10 ensures this developed product and process are effectively managed throughout the commercial lifecycle. Its four key components—process performance monitoring, CAPA, change management, and management review—work together to maintain a state of control and facilitate continuous improvement [17] [18].

Experimental Protocols for Implementing QbD and QRM

Protocol 1: Establishing a QbD-Based Control Strategy for a Solid Dosage Form

The application of QbD is a systematic process that moves from high-level goals to a defined and well-understood control strategy.

- Define the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP): The first step is to create a prospective list of the drug's target quality characteristics. For a solid oral tablet, this typically includes elements such as dosage form, strength, dissolution criteria, stability requirements, and container closure system [21].

- Identify Critical Quality Attributes (CQAs): Using the QTPP as a guide, determine which physicochemical or biological properties are critical to ensuring quality. For a tablet, common CQAs include assay/potency, content uniformity, dissolution rate, impurity profile, and moisture content [21]. A risk assessment is often used to screen and rank potential attributes based on their impact on safety and efficacy.

- Link Raw Materials and Process Parameters to CQAs: This stage employs Design of Experiments (DoE) and risk assessment tools (e.g., Failure Mode and Effects Analysis, FMEA) to understand the relationship between input variables and the CQAs [20]. The goal is to determine which Critical Material Attributes (CMAs) of the ingredients (e.g., API particle size distribution, excipient grade) and which Critical Process Parameters (CPPs) of the unit operations (e.g., blender speed, compression force, granulation endpoint) significantly impact the CQAs.

- Develop and Refine the Design Space: Based on the experimental data, a design space is developed for the CPPs to define their proven acceptable ranges that consistently yield product meeting all CQAs [22]. Operating within this space is not considered a change, providing operational flexibility.

- Implement and Validate the Control Strategy: The control strategy is a comprehensive plan that combines controls for CMAs, CPPs, and in-process tests, along with final product specifications, to ensure the process performs as expected and the product meets its QTPP [20]. This strategy is confirmed during process validation.

Protocol 2: Conducting a Risk Assessment for a Sterile Filling Operation

A practical application of ICH Q9 in a high-risk manufacturing environment involves a structured risk assessment to identify and control critical hazards [22].

- Risk Identification: Assemble a cross-functional team to systematically identify potential hazards (e.g., microbial contamination, endotoxin, incorrect fill volume) using tools like process mapping and historical data analysis [18].

- Risk Analysis: For each identified hazard, evaluate the severity of the impact on the patient and the probability of occurrence. A risk matrix is commonly used, often with a "traffic light" principle (Red/Amber/Green) to visualize priority levels [22] [20].

- Risk Evaluation: Rank the risks based on their analysis. A case study on a sterile-fill operation used this method to identify hazards with a risk priority number (RPN) of ≥105 as critical, requiring immediate and targeted controls [22].

- Risk Control: Implement measures to mitigate high-priority risks. This could include design modifications (e.g., isolator technology), process adjustments (e.g., defined environmental monitoring), and enhanced quality controls (e.g., 100% fill weight checks) [22] [18].

- Risk Review and Communication: Document the entire assessment and communicate the findings to all relevant stakeholders. The risk assessment should be a living document, reviewed periodically and when changes occur to the process or equipment [17].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Lifecycle Management

The implementation of a science- and risk-based approach to analytical methods, in alignment with the ICH Q8-Q10 framework, relies on specific tools and reagents. The USP has advocated for a lifecycle model for analytical procedures, mirroring the concepts used for process validation [23].

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Robust Analytical Methods

| Research Reagent / Material | Critical Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| System Suitability Reference Standards | Verifies that the analytical instrument and procedure are performing as intended at the time of the test. Essential for demonstrating method reproducibility and reliability as per ICH Q2. |

| Pharmaceutical Grade Reference Standards | Provides the definitive, highly characterized substance for identifying and quantifying the Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient (API) and its impurities. Critical for accurate method development and validation. |

| Process-Related Impurity Standards | Used to qualify and validate methods for specific impurities identified during risk assessment (ICH Q9). Enables accurate tracking and control of impurities as outlined in ICH Q3. |

| Stable Isotope-Labeled Internal Standards | Improves the accuracy and precision of mass spectrometry-based methods (e.g., LC-MS/MS) by correcting for variability in sample preparation and ionization. Key for robust bioanalytical methods. |

| Chromatography Columns & Consumables | Specific columns (e.g., UPLC, HPLC) and high-purity solvents/mobile phases are critical material attributes (CMAs) for chromatographic methods. Their consistent performance is vital for method robustness. |

The ICH Q8, Q9, and Q10 guidelines collectively provide a powerful, integrated framework for achieving a modern, robust pharmaceutical quality system. By moving from a reactive, quality-by-testing paradigm to a proactive, science- and risk-based approach, the industry can achieve significant benefits: enhanced product quality and patient safety, improved regulatory compliance, and increased operational efficiency through more strategic resource allocation [18]. The successful integration of these guidelines—where Q8 provides the scientific roadmap, Q9 enables risk-informed decision-making, and Q10 ensures effective lifecycle management—is the cornerstone of a maximally efficient and agile pharmaceutical manufacturing sector capable of reliably delivering high-quality medicines to patients [21] [19].

From Theory to Practice: Implementing ICH Q2(R2) Parameters in Stability Studies

Defining the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) for Stability-Indicating Methods

In the pharmaceutical industry, ensuring the quality, safety, and efficacy of drug substances and products over their shelf life is paramount. Stability-indicating methods (SIMs) are analytical procedures specifically designed and validated to measure the quality attributes of drug substances and products while reliably discriminating between the active pharmaceutical ingredient (API) and its potential degradation products [24]. Within the framework of International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines and the Quality by Design (QbD) paradigm, the Analytical Target Profile (ATP) has emerged as a foundational concept for the lifecycle management of these critical methods [25]. The ATP is defined as a prospective summary of the performance requirements for an analytical procedure, outlining the quality criteria that a reportable result must meet to ensure confidence in the decisions made about a product's quality and stability [25] [26]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the ATP-centric approach against traditional method development, detailing the experimental protocols and data requirements for defining the ATP for stability-indicating methods in compliance with ICH guidelines.

Core Concepts: ATP, QbD, and ICH Stability Guidelines

The Analytical Target Profile (ATP) Defined

The ATP serves as the cornerstone for analytical method development and validation, much like the Quality Target Product Profile (QTPP) does for drug product development. In essence, the ATP specifies the required quality of the reportable result generated by the analytical method. It defines the maximum allowable uncertainty associated with a measurement, ensuring the result is fit for its intended purpose in making quality decisions [25]. For a stability-indicating method, the primary purpose is to accurately monitor the potency of the API and quantify the appearance of degradation products over time, thereby supporting the assignment of a scientifically justified shelf life.

The QbD Paradigm in Analytical Development

The implementation of QbD principles in analytical development, as mandated by ICH Q8, shifts the focus from merely testing quality into building it into the method from the outset [26]. This systematic approach involves:

- Defining the ATP: Clearly stating the method's purpose and required performance.

- Identifying Critical Method Attributes (CMAs): These are the performance characteristics of the method, such as specificity, accuracy, and precision, that must be controlled to ensure the ATP is met.

- Identifying Critical Method Parameters (CMPs): These are the variables in the analytical procedure (e.g., mobile phase composition, column temperature, flow rate) that can impact the CMAs.

- Establishing a Method Operable Design Region (MODR): The multidimensional combination of CMPs within which variations do not adversely affect the method's ability to meet the ATP, ensuring robustness [26].

The Regulatory Landscape: ICH Guidelines for Stability

Stability testing is rigorously defined by a suite of ICH guidelines. ICH Q1A(R2) provides the core protocol for stability testing, defining the storage conditions (e.g., 25°C ± 2°C/60% RH ± 5% RH for long-term studies) and minimum timeframes (e.g., 12 months for long-term data) required for registration applications [15] [27]. ICH Q1B addresses photostability testing, while ICH Q2(R1) outlines the validation of analytical procedures. The development of ICH Q14 and the revision of ICH Q2(R1) aim to formally harmonize and integrate modern, QbD-based concepts like the ATP into the analytical lifecycle [25].

The following workflow illustrates how the ATP drives the analytical method lifecycle within the QbD framework and its connection to product stability studies:

Comparative Analysis: ATP-Driven vs. Traditional Method Development

The adoption of an ATP-driven, QbD-based approach represents a significant evolution from traditional method development practices. The table below summarizes the key differences between these two paradigms.

Table 1: Comparison of ATP-Driven (QbD) and Traditional Analytical Method Development

| Aspect | ATP-Driven / QbD Approach | Traditional Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Philosophy | Quality is built into the method design from the start [26]. | Quality is tested into the method at the end of development. |

| Focus | Fitness for purpose; quality of the reportable result [25]. | Adherence to a fixed set of operational conditions. |

| Development Process | Systematic, using structured risk assessment and Design of Experiments (DoE) [26]. | Often sequential, one-factor-at-a-time (OFAT). |

| Robustness | Formally assessed and understood through a defined Method Operable Design Region (MODR) [26]. | Typically tested at the end of development with limited scope. |

| Regulatory Flexibility | Higher potential for flexibility via established performance-based conditions (ICH Q12) [25]. | Less flexible; changes often require regulatory notification. |

| Lifecycle Management | Continuous improvement guided by the ATP [25]. | Changes may require a new validation. |

The ATP-driven approach offers several distinct advantages. It provides a clear and unambiguous target for method development and validation, which enhances communication between development teams and regulatory agencies. By focusing on the performance of the reportable result rather than a specific technique, it can facilitate technological advancements and method improvements without necessitating major regulatory submissions, as long as the ATP continues to be met [25]. This is particularly valuable for long-term stability studies, where a method might need to be transferred or updated over its lifespan.

Defining the ATP for a Stability-Indicating Method

Key Components of the ATP

For a stability-indicating method, the ATP must explicitly define the criteria that ensure accurate quantification of the API and its degradation products. The core components include:

- Analyte and Matrix: Clearly define the analyte (e.g., specific API) and the matrix (e.g., drug product formulation including all excipients).

- Reportable Result: Specify the type of result needed (e.g., % assay of label claim, % of specific degradation product).

- Acceptable Uncertainty: Define the maximum combined uncertainty for the reportable result, which integrates specificity, accuracy, and precision [25].

- Range: Define the expected concentration range over which the method must perform, from the low level of degradation impurities to the high level of the API in the drug product [25].

Experimental Protocols for ATP Verification

The verification of an ATP for a stability-indicating method relies on a set of rigorously designed experiments, primarily centered on forced degradation studies and method validation.

Forced Degradation Studies (Stress Testing)

Forced degradation studies are critical for demonstrating the stability-indicating power of the method. These studies involve intentionally degrading the drug substance or product under various stress conditions to generate degradation products [24]. The experimental protocol generally includes:

- Acidic and Basic Hydrolysis: Treatment with acids (e.g., 0.75 N HCl) or bases (e.g., 0.03 N NaOH) at elevated temperatures (e.g., 25-75°C) for a defined period [26].

- Oxidative Degradation: Treatment with oxidizing agents like hydrogen peroxide (e.g., 10% H₂O₂) under reflux at elevated temperatures (e.g., 50°C) [26].

- Thermal and Photolytic Degradation: Exposure to dry heat and controlled light as per ICH Q1B.

The method must be able to separate and resolve the API from all generated degradation products, proving its specificity. The use of hyphenated techniques like HPLC-DAD and LC-MS is highly recommended for this purpose, as they allow for parallel quantitative analysis and qualitative identification of impurities [24].

Validation of Critical Method Performance Characteristics

The following table outlines the key performance characteristics defined in the ATP and their corresponding experimental protocols for validation.

Table 2: Key ATP Requirements and Corresponding Experimental Validation Protocols

| ATP Requirement | Experimental Validation Protocol | Typical Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity/Selectivity | Inject samples from forced degradation studies. The method should resolve the API from all known and unknown degradation products [24]. | Peak purity index for the API peak passes; resolution from closest eluting peak > 2.0 [24] [26]. |

| Accuracy | Spike the API into the placebo or sample matrix at multiple concentration levels (e.g., 50%, 100%, 150%). Calculate recovery of the known amount [24]. | Mean recovery between 98.0% - 102.0% for the API. |

| Precision | - Repeatability: Multiple injections of a homogeneous sample (e.g., n=6) at 100% concentration.- Intermediate Precision: Repeat the analysis on a different day, with a different analyst, or different instrument [24]. | Relative Standard Deviation (RSD) ≤ 2.0% for the API assay. |

| Linearity & Range | Prepare and analyze standard solutions at a minimum of 5 concentration levels across a specified range (e.g., 50-150% of target concentration) [26]. | Correlation coefficient (r) > 0.999. |

| Robustness | Deliberately vary critical method parameters (CMPs) such as mobile phase pH (±0.1), temperature (±2°C), and flow rate (±10%) using a structured DoE (e.g., fractional factorial design) [26]. | All samples meet system suitability criteria despite variations. |

Case Study: Application of the ATP for a Green HPLC Method

A 2023 study on developing a green stability-indicating method for the concomitant analysis of fluorescein sodium and benoxinate hydrochloride provides an excellent example of the ATP and QbD in practice [26].

- ATP Definition: The goal was a "green, robust and fast stability indicating chromatographic method" for analyzing both drugs in the presence of degradation products within four minutes, replacing toxic solvents with eco-friendly alternatives [26].

- CMPs and CMAs: Critical Method Parameters screened via Fractional Factorial Design (FFD) included buffer pH, % of organic modifier, and column temperature. The Critical Method Attributes included resolution between peaks, analysis time, and greenness scores (Ecoscale, EAT) [26].

- Optimization: A Box-Behnken Design (BBD) was then used to model the relationship between CMPs and CMAs and to find the optimal MODR [26].

- Outcome: The optimized method used an isopropanol/phosphate buffer mobile phase, achieved analysis in under 4 minutes, and was validated for specificity across forced degradation studies (acidic, basic, oxidative), demonstrating successful ATP attainment [26].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Stability-Indicating Method Development

| Item | Function/Explanation |

|---|---|

| Chromatography System (HPLC/UHPLC) | Equipped with a DAD or PDA detector for peak purity assessment and hyphenation with Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS) for impurity identification [24] [26]. |

| C18 Chromatography Column | The most common stationary phase for reverse-phase separation of APIs and their degradation products [26]. |

| Buffers & Mobile Phases | e.g., Potassium dihydrogen phosphate for pH control; green solvents like Isopropanol or Ethanol as organic modifiers to replace acetonitrile [26]. |

| Forced Degradation Reagents | e.g., Hydrochloric Acid (HCl), Sodium Hydroxide (NaOH), Hydrogen Peroxide (Hâ‚‚Oâ‚‚) for generating degradation products under stress conditions [26]. |

| Design of Experiments (DoE) Software | Essential for systematic screening (e.g., FFD) and optimization (e.g., BBD) of method parameters, ensuring a robust MODR [26]. |

| EN106 | EN106, CAS:757192-67-9, MF:C13H13ClN2O3, MW:280.70 g/mol |

| EGFR-IN-146 | 2-phenyl-N-(pyridin-3-ylmethyl)quinazolin-4-amine |

The Analytical Target Profile is a powerful tool that aligns analytical method development with the core principles of Quality by Design and the rigorous requirements of ICH stability guidelines. By prospectively defining the required quality of the reportable result, the ATP ensures that stability-indicating methods are fit for their purpose of reliably monitoring drug quality throughout its shelf life. The comparative data and experimental protocols detailed in this guide demonstrate that an ATP-driven approach provides a more systematic, robust, and scientifically justified framework for method development compared to traditional practices. As the regulatory landscape evolves with ICH Q14, adopting the ATP concept will be crucial for pharmaceutical scientists and drug development professionals to achieve regulatory flexibility, enhance product quality, and ensure patient safety.

Within the pharmaceutical industry, demonstrating the stability of a drug substance or product is a regulatory imperative. This process relies heavily on analytical methods that can accurately and reliably quantify the active ingredient and monitor the formation of impurities over time. The validity of any stability conclusion is therefore intrinsically tied to the validity of the analytical procedure used. Analytical method validation provides the documented evidence that a method is fit-for-purpose, ensuring that the data generated for stability studies are trustworthy and scientifically sound [28] [29].

The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) provides the harmonized framework for this validation, primarily through the Q2(R2) guideline on the validation of analytical procedures and the complementary Q14 guideline on analytical procedure development [28]. For professionals engaged in drug development, adherence to these guidelines is not merely a regulatory formality but a critical component of quality by design. It ensures that methods are capable of detecting changes in product quality attributes, such as a decrease in assay value or an increase in degradation products, which are essential for establishing a product's shelf life and storage conditions. This guide focuses on the five core parameters—Specificity, Accuracy, Precision, Linearity, and Range—that form the foundation of any validation protocol for drug stability testing.

Core Validation Parameters: Definitions and Experimental Protocols

The following sections detail each of the five core validation parameters, defining their significance and outlining the standard experimental protocols as per ICH guidelines.

Specificity

Definition and Significance: Specificity is the ability of an analytical procedure to assess the analyte unequivocally in the presence of components that may be expected to be present, such as impurities, degradants, or excipients [30] [28]. For stability-indicating methods, this is the most critical parameter. The method must be able to distinguish and quantify the analyte from its degradation products to provide an accurate stability profile.

Experimental Protocol: To demonstrate specificity, samples of the drug substance or product are subjected to stress conditions (e.g., acid, base, oxidation, thermal, and photolytic degradation) to generate degradants. The chromatogram of the degraded sample is then compared to that of a pure reference standard.

- Peak Purity Assessment: This is a crucial test, performed using a photodiode array (PDA) detector or mass spectrometry (MS). The software assesses the spectra across the entire analyte peak to confirm the absence of co-eluting impurities [29].

- Resolution: The resolution between the analyte peak and the closest eluting potential interferent must meet predefined acceptance criteria (e.g., Resolution > 1.5) [29].

Accuracy

Definition and Significance: Accuracy expresses the closeness of agreement between the value found and the value accepted as a true or reference value [30] [28]. It is a measure of trueness and is often reported as percent recovery. In the context of a stability test, an accurate method ensures that the reported potency or impurity level is a true reflection of the sample's quality.

Experimental Protocol: Accuracy is typically established by spiking the drug product with known quantities of the analyte.

- Sample Preparation: A minimum of nine determinations over a minimum of three concentration levels (e.g., 80%, 100%, 120% of the target concentration) covering the specified range should be performed [30] [29].

- Calculation: The recovery for each level is calculated as (Measured Concentration / Spiked Concentration) × 100%. The mean recovery across all levels should fall within predefined acceptance criteria, often 98–102% for the assay of an active ingredient [28].

Precision

Definition and Significance: Precision expresses the closeness of agreement between a series of measurements obtained from multiple sampling of the same homogeneous sample under prescribed conditions [30]. It is a measure of method variability and is subdivided into three levels:

- Repeatability (Intra-assay Precision): Precision under the same operating conditions over a short interval of time [29].

- Intermediate Precision: Precision within the same laboratory, incorporating variations like different days, different analysts, or different equipment [29].

- Reproducibility: Precision between different laboratories (assessed during method transfer) [29].

Experimental Protocol:

- Repeatability: Analyze a minimum of six determinations at 100% of the test concentration or nine determinations covering the specified range (e.g., three concentrations with three replicates each) [29].

- Intermediate Precision: A second analyst performs the same procedure on a different day, often using a different HPLC system. The results from both analysts are compared, and the % relative standard deviation (%RSD) is calculated for the combined data set [29].

- Data Reporting: Precision results are reported as the %RSD. For an assay method, an %RSD of ≤ 1.5% is often acceptable for repeatability [28].

Linearity and Range

Definition and Significance:

- Linearity is the ability of the method to obtain test results that are directly proportional to the concentration of the analyte within a given range [30] [31].

- Range is the interval between the upper and lower concentrations of analyte for which it has been demonstrated that the method has a suitable level of precision, accuracy, and linearity [30].

Experimental Protocol:

- Linearity: A series of standard solutions (a minimum of five) are prepared across the anticipated range (e.g., 50-150% of the target concentration). The responses are plotted against concentrations, and a linear regression model is applied. The correlation coefficient (r), y-intercept, and slope are reported. A correlation coefficient of >0.999 is typically expected for assay methods [28] [29].

- Range: The range is validated by demonstrating that the method meets the acceptance criteria for accuracy, precision, and linearity at the extremes and within the interval.

Table 1: Summary of Core Validation Parameters and Protocols

| Parameter | Experimental Methodology | Key Acceptance Criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | Analyze stressed samples; check peak purity via PDA or MS; measure resolution from closest eluting peak. | No co-elution; peak purity passes; resolution >1.5 [29]. |

| Accuracy | Analyze replicate samples (n≥9) at three concentration levels; calculate % recovery. | Mean recovery of 98-102% (for assay) [28] [29]. |

| Precision | Analyze homogeneous samples multiple times for repeatability; involve different analysts/days for intermediate precision. | %RSD ≤ 1.5% (for repeatability of assay) [28] [29]. |

| Linearity | Analyze a minimum of 5 concentrations across the specified range; perform linear regression. | Correlation coefficient (r) > 0.999 [28] [29]. |

| Range | Demonstrate that accuracy, precision, and linearity are acceptable across the entire range (e.g., 80-120% of target). | Meets all criteria for accuracy, precision, and linearity at the range limits [30]. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Validation Activities

This section provides detailed workflows for two fundamental validation experiments.

Protocol for a Method Comparison Study

When validating a new method (test method), it is often compared against an established one. This is critical for assessing systematic error or bias [32] [33].

- Selection of Comparative Method: Ideally, a well-characterized reference method should be used. If using a routine method, any large discrepancies must be interpreted with caution [32].

- Sample Selection: A minimum of 40 different patient specimens is recommended. These should be carefully selected to cover the entire working range of the method [32].

- Experimental Execution: Each specimen is analyzed by both the test and comparative methods. Analysis should be performed over a minimum of 5 different days to account for run-to-run variability. Specimens should be analyzed by both methods within a short time frame (e.g., two hours) to ensure stability [32].

- Data Analysis:

- Graphical Analysis: Use a Bland-Altman plot, where the x-axis is the average of the two methods and the y-axis is the difference between them (test minus comparative). This helps visualize bias and its consistency across the concentration range [33].

- Statistical Analysis: Calculate the average difference (bias) and the standard deviation of the differences. The limits of agreement are defined as Bias ± 1.96 × SD [33]. For data covering a wide range, linear regression (Y = a + bX) is used to estimate proportional and constant error [32].

The diagram below illustrates the logical workflow for this experiment.

Figure 1: Workflow for a Method Comparison Experiment

Protocol for a Robustness Evaluation

Robustness is the capacity of a method to remain unaffected by small, deliberate variations in method parameters [30] [29].

- Identify Key Parameters: Determine critical method variables (e.g., mobile phase pH, composition, column temperature, flow rate, different columns).

- Experimental Design: A bracketing approach is used, where each parameter is varied slightly around the specified optimum value while keeping others constant.

- Execution: A standard sample (often at 100% concentration) is analyzed under each varied condition.

- Assessment: Monitor the impact on critical performance attributes, such as resolution from a critical pair, tailing factor, and theoretical plates. The method is considered robust if these attributes remain within acceptance criteria despite the variations [30].

Comparative Analysis: A Case Study on Metoprolol Tartrate Assay

A 2024 study provides an excellent comparative analysis of two analytical techniques for quantifying Metoprolol Tartrate (MET) in pharmaceuticals: Ultra-Fast Liquid Chromatography with DAD detection (UFLC-DAD) and UV-Spectrophotometry [34]. This case study highlights the practical trade-offs between different analytical approaches.

Experimental Overview: Both methods were optimized and fully validated according to ICH guidelines. The UFLC-DAD method involved chromatographic separation, while the spectrophotometric method measured absorbance directly at 223 nm. The methods were compared based on their validation results and an assessment of their environmental impact using the Analytical GREEnness (AGREE) metric [34].

Table 2: Comparison of UFLC-DAD and UV-Spectrophotometry for Drug Assay

| Validation Parameter | UFLC-DAD Method | UV-Spectrophotometry Method |

|---|---|---|

| Specificity | High (Separation of analyte from excipients) [34] | Lower (Potential interference from excipients; cannot resolve mixtures) [34] |

| Linearity Range | Wider dynamic range [34] | Limited to a narrower range of concentrations [34] |

| Sensitivity (LOD/LOQ) | Higher sensitivity (Lower LOD and LOQ) [34] | Lower sensitivity (Higher LOD and LOQ) [34] |

| Operation & Cost | Complex operation, higher cost, longer analysis time [34] | Simple operation, low cost, rapid analysis [34] |

| Sample Consumption | Lower sample volume required [34] | Larger sample volume needed for analysis [34] |

| Environmental Impact | Lower greenness score [34] | Higher greenness score [34] |

Conclusion of the Case Study: The study concluded that the UFLC-DAD method was superior for specificity, sensitivity, and application across different dosage strengths. However, for the routine quality control of a single dosage form where specificity was not a primary concern, the UV-spectrophotometric method offered a valid, cost-effective, and greener alternative [34]. This demonstrates that the "best" method depends on the intended application and available resources.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table lists key materials and reagents essential for conducting robust analytical method validation, particularly for chromatographic assays.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Analytical Validation

| Item | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Reference Standard | Serves as the benchmark for accuracy and linearity testing; its accepted concentration is the "true value" [29]. |

| Placebo/Excipient Blend | Used in specificity and accuracy experiments to confirm the absence of interference from non-active components [29]. |

| Forced Degradation Samples | Stressed samples (acid, base, oxidative, thermal, photolytic) used to demonstrate the specificity of a stability-indicating method [29]. |

| Mobile Phase Components | High-purity solvents and buffers are critical for achieving robust and reproducible chromatographic separation. |

| System Suitability Test Solutions | A reference preparation used to verify that the chromatographic system is performing adequately before and during validation runs [28] [29]. |

| Bergamottin | Bergamottin, MF:C21H22O4, MW:338.4 g/mol |

| Valone | Valone, CAS:145470-90-2, MF:C14H14O3, MW:230.26 g/mol |

In the realm of pharmaceutical development, controlling impurities is a fundamental aspect of ensuring drug safety and efficacy. The International Council for Harmonisation (ICH) guidelines Q2(R2) and Q14 emphasize that analytical procedures should be validated for their intended use, particularly for the detection and quantification of very low levels of impurities and degradation products [35]. Within this framework, the Limit of Detection (LOD) and Limit of Quantitation (LOQ) are two pivotal performance characteristics that define the lowest concentrations at which an analyte can be reliably detected or quantified, respectively [36] [37]. Establishing these limits is not merely a regulatory checkbox; it is a critical exercise that defines the capability and limitations of an analytical method, ensuring it is "fit for purpose" for drug stability testing and impurity profiling [36] [38]. This guide provides a practical comparison of the methodologies for determining LOD and LOQ, underpinned by experimental protocols and data relevant to researchers and drug development professionals.

Fundamental Concepts and Definitions

Understanding the distinct meanings of LOD and LOQ is essential for their correct application.

Limit of Detection (LOD): The LOD is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be detected—but not necessarily quantified as an exact value—by the analytical procedure [39]. At this level, the analyte's signal can be distinguished from the background noise with a stated confidence level, typically 99% [39]. It is the point of decision, answering the question: "Is the analyte present or not?"

Limit of Quantitation (LOQ): The LOQ is the lowest concentration of an analyte that can be quantitatively determined with acceptable precision (repeatability) and accuracy (trueness) under stated experimental conditions [36] [37]. While the LOD confirms presence, the LOQ ensures that the numerical value generated is reliable enough for making informed decisions.

A third related term, the Limit of Blank (LoB), is often used as a statistical foundation. The LoB is the highest apparent analyte concentration expected to be found when replicates of a blank sample (containing no analyte) are tested [36]. The relationships and evolution from blank to detection to quantitation are visually summarized in the following workflow.

Methodological Comparison: How to Determine LOD and LOQ