Validating Animal Disease Models in Pharmacology: Strategies to Enhance Predictive Power and Translation

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating animal disease models.

Validating Animal Disease Models in Pharmacology: Strategies to Enhance Predictive Power and Translation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on the critical process of validating animal disease models. It explores the foundational principles of why validation is essential for improving clinical translation, details established and emerging methodological frameworks for model assessment, addresses common challenges and optimization strategies, and compares validation approaches across different disease areas. By synthesizing current tools and evidence, this resource aims to equip scientists with the knowledge to select and justify animal models more effectively, thereby enhancing the efficiency and success of preclinical drug development.

The Critical Need for Model Validation: Foundations for Successful Translation

The Quantitative Landscape of Drug Development Attrition

The path of a new drug from discovery to market is a marathon of attrition, characterized by staggering failure rates and immense financial investment. Industry analyses consistently show that the average development timeline spans 10 to 15 years, with capitalized costs averaging $2.6 billion per approved drug [1]. The primary driver of this cost is the high failure rate during clinical development, where the likelihood of approval (LOA) for a drug candidate entering Phase I trials is a mere 7.9% [1]. This means more than nine out of every ten drugs that begin human testing will fail [1].

Recent dynamic analysis of clinical trial success rates (ClinSR) indicates that after a period of decline since the early 21st century, success rates have recently hit a plateau and are beginning to show signs of increase [2]. However, significant challenges persist. As of 2024, the success rate for Phase 1 drugs has plummeted to just 6.7%, compared to 10% a decade ago [3]. This contributes to a falling internal rate of return for R&D investment, which has dropped to 4.1%—well below the cost of capital [3].

Table 1: Drug Development Lifecycle by the Numbers

| Development Stage | Average Duration | Probability of Transition to Next Stage | Primary Reason for Failure |

|---|---|---|---|

| Discovery & Preclinical | 2-4 years | ~0.01% (to approval) | Toxicity, lack of effectiveness in models [1] |

| Phase I | 2.3 years | 52% - 70% | Unmanageable toxicity/safety [1] |

| Phase II | 3.6 years | 29% - 40% | Lack of clinical efficacy [1] |

| Phase III | 3.3 years | 58% - 65% | Insufficient efficacy, safety in larger populations [1] |

| FDA Review | 1.3 years | ~91% | Safety/efficacy concerns in submitted data [1] |

The failure rates vary substantially by therapeutic area. An analysis of phase-transition probabilities reveals that drugs for hematological disorders have the highest likelihood of approval from Phase I at 23.9%, while urology drugs have the lowest at just 3.6% [1]. The Phase II stage represents the single largest hurdle in drug development, where between 40% and 50% of all clinical failures occur due to a lack of clinical efficacy [1].

Table 2: Clinical Trial Success Rates by Therapeutic Area (2025 Analysis)

| Therapeutic Area | Phase I to Approval Success Rate | Notable Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Oncology | Tracked slightly behind 2024 approvals in H1 2025 [4] | High biological complexity, tumor heterogeneity |

| Hematology | 23.9% (Highest) [1] | - |

| Urology | 3.6% (Lowest) [1] | - |

| Anti-COVID-19 Drugs | Extremely low ClinSR [2] | Compressed development timelines, novel mechanisms |

| Drug Repurposing | Unexpectedly lower than new drugs [2] | May involve off-target effects or novel biology |

Animal Models in Preclinical Validation: Benefits and Limitations

Validation Criteria for Animal Models

The value of an animal model in predicting human outcomes depends on how well it meets three established validation criteria first proposed by Willner in 1984 and now widely accepted across biomedical research [5].

Predictive Validity: This is considered the most crucial criterion, especially in preclinical drug discovery [5]. It measures how well results from the model correlate with human therapeutic outcomes. An example is the 6-OHDA rodent model for Parkinson's disease, which has been valuable for predicting treatment response [5].

Face Validity: This assesses how closely the model replicates the phenotypic manifestations of the human disease. The MPTP non-human primate model for Parkinson's Disease, for instance, effectively reproduces many of the motor symptoms seen in humans [5].

Construct Validity: This examines how well the method used to induce the disease in animals reflects the currently understood etiology and biological mechanisms of the human disease. Transgenic mouse models for Spinal Muscular Atrophy, which incorporate human SMN genes, exemplify strong construct validity [5].

Limitations in Translational Predictivity

Despite these validation frameworks, no single animal model perfectly replicates clinical conditions or shows validity in all three criteria [5]. A model might have strong predictive validity but completely lack face validity, or vice versa [5]. This inherent limitation contributes to what is known as the "translation crisis."

Significant physiological differences between animals and humans lead to problematic disparities in drug metabolism, target interactions, and disease pathophysiology [6]. These differences help explain why over 90% of clinical drug development efforts fail [7], with approximately 60% of trials failing due to lack of efficacy and 30% due to toxicity—issues that animal models frequently fail to predict [6].

The field of neurodegenerative disease research has particularly struggled with translatability, whereas areas like oncology have seen improvements through the use of more sophisticated models like patient-derived xenografts (PDX) and humanized models [5] [4].

Emerging Solutions: Advanced Models and Technologies

Integrated Preclinical Model Systems

No single model can fully recapitulate human disease, making a multifactorial approach using complementary models essential for improving translational accuracy [5] [4]. The most effective preclinical screening employs a sequential, integrated strategy that leverages the unique advantages of each model system.

Table 3: Comparison of Preclinical Screening Models in Oncology Research

| Model Type | Key Applications | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Cell Lines [4] | - Initial high-throughput screening- Drug efficacy testing- Combination studies | - Reproducible & standardized- Low-cost & versatile- Large established collections | - Limited tumor heterogeneity- Does not reflect tumor microenvironment |

| Organoids [4] | - Investigate drug responses- Personalized medicine- Predictive biomarker identification | - Preserves patient tumor genetics- Better clinical predictivity than cell lines- More cost-effective than animal models | - More complex/time-consuming to create- Cannot fully represent complete tumor microenvironment |

| Patient-Derived Xenografts (PDX) [4] | - Biomarker discovery/validation- Clinical stratification- Drug combination strategies | - Preserves original tumor architecture- Most clinically relevant preclinical model- Mirrors patient tumor responses | - Expensive & resource-intensive- Low-throughput- Ethical considerations of animal use |

The Role of AI and Data-Driven Approaches

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are transforming drug development by enabling more predictive analysis of complex biological data. AI-driven platforms can identify drug characteristics, patient profiles, and sponsor factors to design trials that are more likely to succeed [3]. Pharmaceutical companies are increasingly leveraging these technologies to:

- Optimize clinical trial designs by identifying clear success/failure criteria and commercially meaningful comparator arms [3]

- Use real-world data to identify and match patients more efficiently to clinical trials [3]

- Build predictive models that assess product consistency and reduce quality control time [7]

- Create digital twins of patients to test new drug candidates before human trials [7]

The FDA has recognized the potential of these approaches, releasing guidance in 2025 on "Considerations for the Use of Artificial Intelligence to Support Regulatory Decision Making for Drug and Biological Products" [6].

Human-Relevant Model Systems

A tidal shift is underway toward more human-relevant models that can substantially reduce the cost and timeline of early-stage drug development [6]. These include:

Organs-on-Chips: Microfluidic devices lined with living human cells that mimic human organ functionality. For example, Liver Chip models have been found to outperform conventional models in predicting drug-induced liver injury [6].

Human Induced Pluripotent Stem Cells (iPSCs): These enable the study of disease mechanisms and drug responses in human cells with specific genetic backgrounds.

Quantitative Computational Models: In silico tools that predict drug metabolism, toxicities, and off-target effects before any physical testing [6].

Regulatory changes are supporting this shift. The FDA Modernization Act 2.0, signed into law in 2022, specifically states the intent to utilize alternatives to animal testing for Investigational New Drug applications [6]. In September 2024, the FDA's CDER accepted its first letter of intent for an organ-on-a-chip technology as a drug development tool [6].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

Integrated Biomarker Discovery Workflow

The early identification and validation of biomarkers is crucial to modern drug development. The following protocol outlines a holistic, multi-stage approach for biomarker hypothesis generation and validation:

Stage 1: Hypothesis Generation (PDX-Derived Cell Lines)

- Method: Utilize PDX-derived cell lines for large-scale screening across diverse genetic backgrounds [4].

- Application: Identify potential correlations between genetic mutations and drug responses through targeted screening [4].

- Output: Generate initial sensitivity or resistance biomarker hypotheses for further validation.

Stage 2: Hypothesis Refinement (Organoid Testing)

- Method: Employ patient-derived organoids to validate biomarker hypotheses in more complex 3D tumor models [4].

- Multiomics Analysis: Integrate genomics, transcriptomics, and proteomics data to identify robust biomarker signatures [4].

- Output: Refined biomarker hypotheses with better clinical relevance.

Stage 3: Preclinical Validation (PDX Models)

- Method: Implement PDX models representing diverse tumor types to validate biomarker hypotheses before clinical trials [4].

- Application: Leverage the preserved tumor architecture and microenvironment of PDX models to understand biomarker distribution within heterogeneous tumors [4].

- Output: Clinically translatable biomarker signatures ready for patient stratification in clinical trials.

Research Reagent Solutions for Preclinical Validation

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Preclinical Oncology Studies

| Reagent / Model System | Function in Research | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| PDX-Derived Cell Lines [4] | Initial high-throughput screening platform | - Drug efficacy testing- Correlation of mutation status with drug response |

| Patient-Derived Organoids [4] | 3D culture preserving tumor characteristics | - Immunotherapy evaluation- Predictive biomarker identification- Safety studies |

| PDX Model Collections [4] | Gold standard for in vivo preclinical studies | - Biomarker discovery/validation- Clinical stratification- Drug combination strategies |

| Organ-on-Chip Devices [6] | Microfluidic devices mimicking human organs | - Prediction of drug-induced liver injury- Disease modeling- Personalized medicine |

| Multiomics Analysis Tools [4] | Integrated genomic, transcriptomic, proteomic analysis | - Biomarker signature refinement- Mechanism of action studies |

The translation crisis in drug development, characterized by persistently high attrition rates, remains a formidable challenge for the pharmaceutical industry. While animal models provide a necessary foundation for preclinical validation, their limitations in predictive validity contribute significantly to clinical failure. The path forward requires a multipronged approach: adopting integrated model systems that leverage the strengths of both traditional and emerging technologies, implementing AI-driven analytical tools to enhance decision-making, and embracing human-relevant models that better recapitulate human disease biology. Through these strategies, researchers can systematically address the validation gaps in preclinical research, ultimately improving the predictability of drug development and accelerating the delivery of effective therapies to patients.

In pharmacology research, the development of new therapeutics relies heavily on preclinical animal models. The validity of these models is paramount, as it determines how well experimental results can predict human outcomes. For researchers and drug development professionals, a rigorous understanding of validity types is not just academic—it is crucial for designing robust studies, interpreting data accurately, and making costly go/no-go decisions in the drug development pipeline. This guide provides a comparative analysis of three core validity principles—face, construct, and predictive validity—within the context of validating animal disease models for pharmacological research.

Defining the Core Validity Types

Validity refers to how accurately a method measures what it claims to measure [8]. In the specific context of animal models, it assesses how well the model represents the human disease and its response to therapeutic intervention.

| Validity Type | Core Question | Level of Formality | Primary Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Face Validity | Does the model appear to measure the intended phenomenon? [8] [9] | Informal, subjective, superficial [10] [11] | Superficial judgment by non-experts or researchers [9] [11] |

| Construct Validity | Does the model accurately measure the underlying theoretical construct? [8] [11] | Formal, theoretical, comprehensive [8] | Convergent and discriminant validity testing [10] [11] |

| Predictive Validity | Does performance on the model predict a concrete future outcome? [8] [11] | Formal, empirical, practical | Correlation with a future "gold standard" criterion [8] [9] |

Face Validity

Face validity is the least scientific measure of validity, as it is a subjective assessment of whether a test or model appears to be suitable for its aims on the surface [8] [9]. For example, an animal model of depression might be considered to have face validity if the animals exhibit behaviors such as lethargy or reduced appetite, which are surface-level symptoms of human depression [11]. While its simplicity makes it useful for initial assessments, it is considered weak evidence for a model's quality because it does not ensure that the model is actually measuring the underlying disease construct [8] [10].

Construct Validity

Construct validity evaluates whether a model truly represents the theoretical concept it is intended to measure [8]. A "construct" is an abstract concept that cannot be directly observed, such as depression, anxiety, or cancer progression [8]. Establishing construct validity requires demonstrating that the model behaves in a manner consistent with the scientific theory of the construct. This is often assessed through two subtypes:

- Convergent Validity: The model shows correlation with other tests or models that measure the same or similar construct [10] [11].

- Discriminant Validity: The model can be differentiated from tests or models that measure different constructs [10].

Predictive Validity

Predictive validity assesses how well the results from a model can forecast a concrete outcome in the future [8] [11]. In pharmacology, this is the gold standard for evaluating an animal model's utility: its ability to predict a drug's efficacy or toxicity in humans [11]. A model has high predictive validity if treatments that are effective in humans also show effectiveness in the animal model, and vice-versa. This is a key focus in the validation of models intended to de-risk clinical trials.

Comparative Analysis in Animal Model Validation

The following table summarizes how each validity type is applied and assessed in the specific context of developing and validating animal disease models for pharmacology.

| Aspect | Face Validity | Construct Validity | Predictive Validity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Role in Pharmacology | Initial, rapid screening of model phenotypes. | Ensuring the model recapitulates the human disease's underlying biology. | Determining the model's utility for forecasting human clinical outcomes. |

| Key Application | Selecting models that exhibit obvious, surface-level symptoms analogous to human disease (e.g., motor deficits in a Parkinson's model). | Demonstrating that the model shares key genetic, molecular, and pathway dysregulations with the human disease. | Using the model for lead compound optimization and toxicology studies to prioritize candidates for clinical trials. |

| Data Type | Qualitative, observational | Multimodal (genomic, proteomic, behavioral, physiological) | Quantitative, empirical (correlation with clinical trial results) |

| Experimental Evidence | - Behavioral tests (e.g., forced swim test for depression) [11]- Pathological inspection (e.g., tumor size) | - Genetic similarity (e.g., transgenic models) [8]- Biomarker profiling (e.g., inflammatory cytokines)- Response to known therapeutics | - Correlation between animal model efficacy and human clinical trial outcomes [11]- Retrospective analysis of successful and failed drugs |

| Limitations | - Does not guarantee accuracy.- Vulnerable to anthropomorphism.- Cannot stand alone as evidence. | - Complex and costly to establish.- Requires a deep, well-defined theoretical understanding of the disease. | - Can be context-dependent (e.g., a model may predict efficacy for one drug class but not another).- Ultimate validation requires years of clinical data. |

Experimental Protocols for Assessment

Protocol for Establishing Face Validity

This protocol outlines the steps for a systematic assessment of a new animal model's face validity for major depressive disorder.

- Objective: To determine if the model exhibits observable symptoms analogous to core human depression symptoms.

- Materials: Animal model cohort, control cohort, standard behavioral testing equipment (e.g., open field, sucrose preference apparatus, forced swim test tank).

- Procedure:

- Define Symptom Domains: Based on clinical criteria (e.g., DSM-5), define the key symptom domains to be modeled (e.g., anhedonia, psychomotor retardation, despair).

- Select Behavioral Assays: Map each domain to a standardized behavioral test (e.g., Sucrose Preference Test for anhedonia, Open Field Test for locomotor activity, Forced Swim Test for behavioral despair).

- Blinded Scoring: Conduct experiments with researchers blinded to the animal groups. Record quantitative and qualitative data.

- Expert/Stakeholder Review: Have pharmacologists and behavioral neuroscientists review the data and rate the apparent relevance of the model to human depression on a Likert scale [11].

- Output: A qualitative profile of the model's surface-level resemblance to the human condition.

Protocol for Establishing Construct Validity

This protocol describes a multimodal approach to assess whether a model accurately reflects the theoretical construct of a specific cancer type.

- Objective: To evaluate the model's alignment with the known human disease biology at multiple levels.

- Materials: Animal model tissues, equipment for omics analyses (RNA-seq, mass spectrometry), histological equipment, validated biomarkers.

- Procedure:

- Convergent Validity Testing:

- Genomics: Compare tumor transcriptome from the model to human tumor databases (e.g., The Cancer Genome Atlas) for pathway enrichment similarity [10].

- Proteomics: Identify key protein biomarkers known to be dysregulated in the human cancer and confirm their presence and activity in the model.

- Pharmacology: Test if the model responds to standard-of-care drugs in a manner consistent with human patient responses.

- Discriminant Validity Testing:

- Demonstrate that the model's molecular profile is distinct from other, related cancer types.

- Show that therapies ineffective in the human disease are also ineffective in the model.

- Convergent Validity Testing:

- Output: A network of evidence showing the model's convergence with the human construct and divergence from unrelated constructs.

Protocol for Establishing Predictive Validity

This protocol uses a retrospective analysis to quantify an animal model's ability to predict human clinical efficacy.

- Objective: To calculate the model's predictive power for drug efficacy.

- Materials: Historical data on a set of drug compounds that have been tested in both the animal model and in human clinical trials.

- Procedure:

- Compound Selection: Assemble a blinded set of compounds, including both known clinically effective drugs and those that failed due to lack of efficacy.

- Model Testing: Review or run the compounds through the animal model to generate efficacy data (e.g., tumor growth inhibition, reduction in pathological score).

- Correlation Analysis: Compare the animal model results with the human clinical outcomes. Calculate metrics such as:

- Sensitivity: Proportion of effective drugs in humans that were positive in the model.

- Specificity: Proportion of ineffective drugs in humans that were negative in the model.

- Overall Predictive Accuracy: Proportion of all compounds correctly classified by the model [11].

- Output: Quantitative measures (sensitivity, specificity, accuracy) of the model's forecasting reliability.

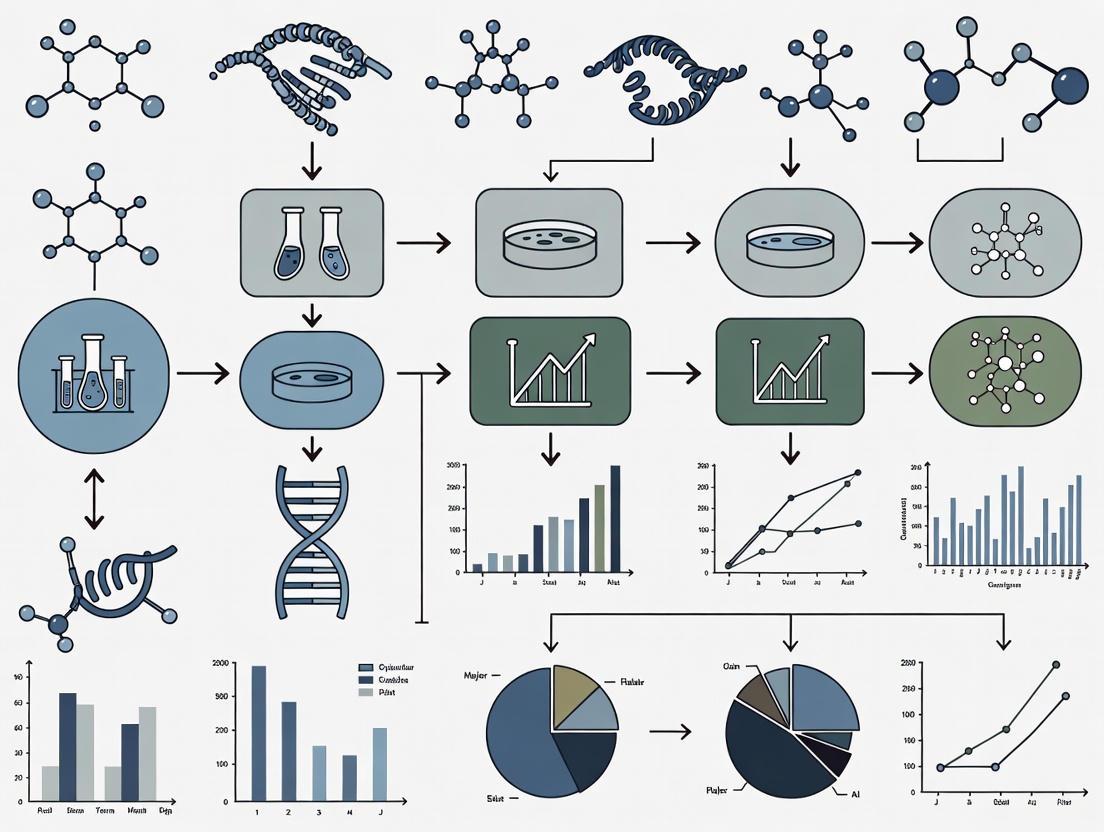

Visualizing the Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the logical sequence and relationships between the different validity assessments in a typical model development pipeline.

Research Reagent Solutions for Validation Studies

The following table details key reagents and tools essential for conducting the experiments described in the validation protocols.

| Reagent/Tool | Function in Validation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Behavioral Test Equipment | Quantifies face validity by measuring disease-relevant behaviors. | Assessing locomotor activity in neurodegenerative disease models; measuring anhedonia via sucrose preference test for depression models. |

| Omics Profiling Kits (e.g., RNA-seq, Proteomics) | Provides molecular data to establish construct validity. | Comparing gene expression profiles between animal tumors and human cancer databases to confirm pathway alignment. |

| Validated Biomarker Assays | Serves as a bridge for convergent validity between animal and human biology. | Measuring circulating inflammatory cytokines in a model of rheumatoid arthritis; assessing cardiac troponin in a cardiotoxicity model. |

| Reference Compounds (Clinical standards & failed drugs) | Critical for assessing both construct and predictive validity. | Establishing that a model responds to known effective drugs (positive control) and does not respond to known ineffective ones (negative control). |

| Microphysiological Systems (Organs-on-a-Chip) | Emerging human-relevant tools used as a comparative standard for animal model validation [12]. | Comparing drug toxicity or efficacy data from an animal model with data from a human liver-on-a-chip to assess translational relevance. |

Face, construct, and predictive validity form a hierarchical framework for validating animal models in pharmacology. While face validity offers an accessible starting point and construct validity ensures biological fidelity, predictive validity remains the ultimate benchmark for a model's utility in drug development. A model strong in all three areas provides the highest confidence for translating preclinical findings to clinical success. As the field evolves with new technologies like AI and human-based microphysiological systems [13] [12] [14], the principles of validity will continue to be the cornerstone for evaluating not only animal models but also these next-generation tools, ensuring rigorous and reliable pharmacology research.

In pharmaceutical research, the selection of a preclinical animal model is a critical determinant of a drug's eventual clinical success. High rates of drug development attrition, often due to insufficient efficacy or unexpected safety issues not predicted by animal studies, have prompted a reevaluation of traditional model validation approaches [15] [16]. While the standard three validity criteria (face, construct, and predictive validity) provide a foundational framework, they often fall short in ensuring translational relevance for complex human diseases. A more rigorous, multidisciplinary assessment that incorporates etiology (disease cause), pathogenesis (disease progression), and histology (tissue pathology) is emerging as essential for optimizing model selection and improving the predictive power of preclinical research [15] [17]. This guide compares animal models across these refined criteria, providing researchers with a structured framework for model selection in pharmacology research.

Comparative Analysis of Animal Disease Models

The following tables provide a quantitative and qualitative comparison of common animal models across key diseases, focusing on their fidelity to human disease characteristics.

Table 1: Comparison of Inflammatory and Metabolic Disease Models

| Disease & Model | Etiological Fidelity | Pathogenetic Fidelity | Histological Concordance | Key Pharmacological Utility | Translatability Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adoptive T-cell Transfer Colitis (Mouse) | Induced (Transfer of T-cells) | Recapitulates immune dysregulation & inflammation | Transmural inflammation, epithelial hyperplasia | Target validation for immune-modulators [15] | High for specific immune mechanisms |

| Chemically-Induced Colitis (e.g., DSS in Mice) | Induced (Chemical damage) | Epithelial barrier disruption → inflammation | Mucosal ulceration, leukocyte infiltration | Screening anti-inflammatory compounds [15] | Moderate (acute injury vs. chronic disease) |

| Zebrafish Diabetes Model | Induced (Chemical/Genetic) | Beta-cell dysfunction, hyperglycemia | Islet morphology changes, not full human pathology | High-throughput screening of metabolic drugs [17] | Moderate for pathways, limited for systemic complications |

| Diet-Induced Obesity (Rodents) | Induced (High-fat diet) | Mirrors human metabolic syndrome: insulin resistance, dyslipidemia | Hepatic steatosis, adipose tissue inflammation | Evaluating weight-loss drugs and insulin sensitizers [17] | High for metabolic syndrome phenotype |

Table 2: Comparison of Infectious Disease and Oncology Models

| Disease & Model | Etiological Fidelity | Pathogenetic Fidelity | Histological Concordance | Key Pharmacological Utility | Translatability Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Syrian Hamster COVID-19 | High (SARS-CoV-2 infection) | Viral replication in respiratory tract → lung inflammation [18] | Mirrors human-like lung pathology and viral load | Vaccine and antiviral efficacy testing [18] | High for respiratory disease progression |

| Humanized Mouse (Oncology) | Variable (Patient-derived xenografts/PDX) | Human tumor in mouse microenvironment | Retains original tumor histoarchitecture | Personalized therapy screening, immunotherapy development [18] [19] | Very High for human-specific drug target interaction |

| Genetically Engineered Mouse (GEMM) for Cancer | High (Specific genetic alterations) | Spontaneous tumor development in immune-competent host | Tumor histology and stroma interaction similar to human | Studying oncogenesis and targeted therapies [19] [17] | High for mechanism-driven drug discovery |

Experimental Protocols for Enhanced Model Validation

Protocol 1: Comprehensive Validation of an Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IBD) Model

This protocol utilizes the Animal Model Quality Assessment (AMQA) tool to ensure translational relevance [15].

- Model Induction and Justification: Justify the selected model (e.g., adoptive T-cell transfer vs. DSS-induced) based on the specific research question (e.g., testing an immunomodulator vs. a barrier-enhancing agent) [15].

- Etiological Assessment: Document how the model's induction method (e.g., specific immune cell population) aligns with known or hypothesized human disease triggers.

- Pathogenetic Profiling:

- Temporal Analysis: Conduct weekly measures of disease activity (e.g., weight, stool consistency, occult blood).

- Cytokine & Immune Phenotyping: Use flow cytometry and multiplex ELISA to profile inflammatory mediators (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, IL-12/23, IFN-γ) in colonic tissue and serum, comparing to human IBD profiles.

- Microbiome Analysis (Optional): Sequence 16S rRNA from fecal samples to assess dysbiosis, a key pathogenic factor in human IBD.

- Histopathological Evaluation:

- Collect and fix colon segments in 10% neutral buffered formalin.

- Process, embed in paraffin, section at 5µm, and stain with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E).

- Score blinded sections using a validated system (e.g., scoring for inflammation severity, crypt loss, architectural distortion, and immune cell infiltration).

- Pharmacological Challenge: Administer a reference therapeutic (e.g., anti-TNF-α antibody) to confirm the model's responsiveness and predictive value for drug classes under investigation.

Protocol 2: Validation of a "Humanized" Mouse Model for Immuno-Oncology

This protocol is critical for evaluating models used to test human-specific immunotherapies [18] [19].

- Model Generation and Characterization:

- Employ NSG or similar immunodeficient mice.

- Engraft with human hematopoietic stem cells (CD34+) or a patient-derived xenograft (PDX).

- Confirm engraftment level (>25% human CD45+ cells in peripheral blood) via flow cytometry at 12-16 weeks post-transplant.

- Etiological and Histological Concordance:

- For PDX models, perform genomic and transcriptomic analysis to verify retention of the original human tumor's key drivers.

- Upon study termination, compare tumor histology from the mouse to the original patient biopsy using H&E and immunohistochemistry for relevant markers (e.g., PD-L1, tumor-specific antigens).

- Functional Pathogenetic Validation:

- Drug Exposure: Treat mice with a human-specific immunotherapy (e.g., anti-PD-1 antibody).

- Endpoint Analysis: Measure tumor volume regression. Harvest tumors for flow cytometric analysis of tumor-infiltrating human lymphocytes (CD8+/CD4+ T-cell ratios, activation markers) to confirm the drug's mechanism of action on the human immune system within the model.

Visualization of Model Validation Workflows

The following diagrams outline the logical workflows for implementing the enhanced validation criteria discussed in this guide.

Diagram 1: A workflow for selecting and validating an animal model for a specific Context of Use (COU), based on the AMQA framework. It emphasizes the sequential evaluation of etiology, pathogenesis, and histology before making a final model selection [15].

Diagram 2: The role of a thoroughly validated animal model within a modern, integrated drug development workflow that also leverages New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) like in silico and in vitro tools [18] [16] [20].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Materials for Advanced Model Validation

| Reagent/Material | Function in Validation | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Species-Specific Cytokine ELISA/Multiplex Kits | Quantifies key inflammatory mediators to profile pathogenesis and drug response. | Measuring TNF-α, IL-6, IL-1β in mouse colitis models to compare to human cytokine profiles [15]. |

| Flow Cytometry Antibody Panels | Characterizes immune cell populations in tissues (infiltration, activation state). | Profiling human T-cell subsets (CD4, CD8, Treg) in "humanized" mouse models for immuno-oncology [18] [19]. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Gene Editing Systems | Creates genetically engineered models (GEMs) with precise etiological mutations. | Generating knockout mice with loss-of-function mutations to mimic human genetic diseases [18] [19]. |

| Patient-Derived Xenograft (PDX) | Provides a histologically accurate and genetically stable tumor for oncology studies. | Transplanting human tumor tissue into immunodeficient mice to test personalized therapy regimens [19]. |

| Organ-on-a-Chip Microfluidic Devices | Serves as a human-relevant complementary tool to de-risk in vivo studies. | Using a human lung-on-a-chip to study SARS-CoV-2 infection pathophysiology before animal testing [18] [16]. |

| IHC/IF Antibodies for Tissue Markers | Enables histological evaluation and scoring of disease-specific pathology. | Staining for collagen deposition in fibrosis models or specific neuronal proteins in neurodegenerative models [15] [17]. |

| 2-Oxoglutaric Acid | 2-Oxoglutaric Acid, CAS:34410-46-3, MF:C5H6O5, MW:146.10 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Afzelin | Afzelin (Kaempferol 3-Rhamnoside) |

The evolving landscape of drug development, marked by both scientific advancement and regulatory shifts toward human-relevant methods [21] [16] [20], demands a more sophisticated approach to animal model validation. Moving beyond the three classic validity criteria to a deeper, evidence-based assessment of etiology, pathogenesis, and histology provides a powerful framework for researchers. This rigorous multi-parameter comparison, supported by the structured tools and protocols outlined in this guide, enables more informed model selection. Ultimately, this enhances the translational predictive value of preclinical pharmacology research, de-risks drug development pipelines, and accelerates the delivery of effective new therapies to patients.

Ethical Imperatives and the 3Rs (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) in Model Selection

The validation of animal disease models represents a cornerstone of pharmacology research, ensuring the translational relevance of therapeutic discoveries. This process is intrinsically guided by the ethical framework of the 3Rs—Replacement, Reduction, and Refinement—first articulated by William Russell and Rex Burch in 1959 [22]. Today, regulatory and scientific evolution is accelerating the integration of these principles into mainstream research practice. The recent FDA Modernization Act 2.0, signed into US law in 2022, has abolished the mandatory requirement for animal testing before advancing to human clinical trials, permitting the use of scientifically valid non-animal methods [23] [12] [24]. This paradigm shift, coupled with initiatives from regulatory bodies like the FDA and EMA to actively phase out animal testing for specific products like monoclonal antibodies, underscores the growing imperative for a more ethical and human-relevant approach to disease modeling [20] [21]. This article objectively compares traditional animal models with emerging 3R-aligned alternatives, evaluating their performance, validation, and application within modern pharmacological research.

The 3Rs Framework: From Principle to Practice

The 3Rs provide a systematic ethical framework for governing the use of animals in science [25] [22].

- Replacement: The use of non-sentient material to replace conscious living higher animals. This can be full replacement (e.g., computer models, human organoids) or partial replacement (e.g., using invertebrates like Drosophila or zebrafish embryos, which are not protected by animal welfare legislation in its entirety) [25] [24].

- Reduction: Employing methods to obtain comparable levels of information from fewer animals, primarily through sophisticated experimental design and statistical analysis [25] [22].

- Refinement: Modifying husbandry or experimental procedures to minimize pain and distress and improve animal welfare [25].

Regulatory agencies worldwide are now working to incorporate this framework. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has published guidelines on the regulatory acceptance of 3R testing approaches [26], while the FDA has detailed specific contexts—from safety pharmacology to chronic toxicity studies—where streamlined nonclinical programs and reduced animal use are acceptable [20].

Comparative Analysis of Model Systems: Performance and Validation

The selection of a model requires a careful balance of ethical considerations, biological relevance, and predictive validity. The following sections and tables provide a comparative analysis of various models.

Traditional Animal Models: Utility and Limitations in Pharmacology

Animal models, from rodents to non-human primates, have been invaluable for understanding whole-body physiology, complex immune responses, and long-term safety profiles [27] [12]. Their use is rooted in the phylogenetic and physiological resemblance to humans, especially in mammals [27]. However, their predictive validity for human outcomes is not guaranteed, as illustrated by the stark contrast between high success rates in animal models and the >99% clinical trial failure rate in Alzheimer's disease [28].

Table 1: Advantages and Limitations of Selected Traditional Animal Models

| Animal Model | Significances and Common Uses | Key Limitations and Ethical Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Mice/Rats | Easy breeding, low cost, well-established genome, many transgenic strains; used in cancer, cardiovascular, and genetic studies [27]. | High inbreeding limits genetic diversity; not ideal for all human disease responses (e.g., inflammation); findings not always translatable [27]. |

| Non-Human Primates | Close genetic and physiological similarity to humans; critical for AIDS, Parkinson's, and vaccine research [27]. | Highest ethical constraints; expensive; long maturity period; specialized housing required [27]. |

| Zebrafish | Vertebrate with high genetic similarity; transparent embryos for developmental biology and toxicology; high regenerative capacity [27] [24]. | Less resemblance to human anatomy and physiology than mammals; not ideal for all disease studies [27]. |

| Guinea Pigs | Outbred model suitable for asthma, tuberculosis, and vaccine research [27]. | High phenotypic variation; limited use for some pathogens (e.g., Ebola) [27]. |

New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) as Replacements and Refinements

NAMs encompass a suite of non-animal technologies designed to provide more human-relevant safety and efficacy data [20] [23]. Their adoption is a key component of the FDA's plan to reduce animal testing [21].

Table 2: Performance and Validation of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs)

| Methodology | Description and Experimental Protocol | Performance Data and Regulatory Context |

|---|---|---|

| In Silico Modelling | Uses computational tools, AI, and machine learning to simulate drug pharmacokinetics (e.g., PBPK models) and predict toxicity [12] [24]. | A computer model for cardiac arrhythmia risk prediction demonstrated ~90% accuracy, compared to ~75% from traditional animal-based hERG testing [24]. |

| Organ-on-a-Chip (OoC) | Microfluidic devices with human cells that mimic the structure and function of human organs (e.g., lung, gut, liver) [12] [24]. | Roche has developed a commercial colon-on-a-chip using a patient's own cells to replicate the gastrointestinal tract for personalized therapy testing [24]. |

| Organoids | 3D cell cultures from human stem cells that model complex tissue interactions and disease mechanisms [12]. | Used for high-throughput compound screening and studying disease pathways in a human-relevant context [12]. |

| In Vitro Assays | Use of cultured human cells combined with high-content imaging and 'omics' technologies to study mechanisms of action and toxicology [12]. | In vitro liver models are accepted by the FDA to predict hepatotoxicity and drug-induced liver injury by assessing biomarker changes [20]. |

Experimental Validation and Workflow in 3R-Compliant Research

Adopting 3R-aligned models requires a rigorous and structured approach to validation. The following workflow diagrams and reagent toolkit outline the key components of this process.

Decision Workflow for 3R-Compliant Model Selection

This diagram illustrates the logical process a researcher should follow to select the most appropriate and ethical model for a pharmacological study, in line with the 3Rs hierarchy.

Integrated Strategy for Model Validation

This diagram outlines an integrated testing strategy (IATA) that combines multiple NAMs to build a robust, non-animal safety assessment, as encouraged by organizations like the OECD [23].

Research Reagent Solutions for 3R-Aligned Pharmacology

This table details key reagents and platforms essential for implementing advanced, non-animal research methodologies.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for 3R-Compliant Research

| Reagent/Platform | Function in Experimental Protocol |

|---|---|

| Recombinant Antibodies | Non-animal-derived antibodies (e.g., from the PETA/ARDF Recombinant Antibody Challenge) that replace animal-derived monoclonal or polyclonal antibodies in research and testing [25]. |

| Stem Cells (Human) | Source material for generating organoids and populating organ-on-a-chip systems to create human-relevant disease and toxicity models [12] [24]. |

| Microfluidic Chips | The physical platform for organ-on-a-chip devices, enabling precise control of cell microenvironments and fluid flow to mimic human organ physiology [12] [24]. |

| QSAR Models & AOPs | Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models and Adverse Outcome Pathways (AOPs) are computational tools used as part of Integrated Approaches to Testing and Assessment (IATA) to predict chemical toxicity without animal tests [23]. |

| GastroPlus/Simcyp | Established software platforms that utilise PBPK modelling and simulation to predict oral bioavailability and inform formulation strategies, replacing certain animal pharmacokinetic studies [24]. |

The validation of animal disease models is undergoing a profound transformation, driven by the ethical imperatives of the 3Rs and supported by rapid technological advancement. Regulatory changes, such as the FDA Modernization Act 2.0, have provided the necessary impetus for the scientific community to embrace NAMs not merely as alternatives, but as superior, more human-predictive tools [21] [23] [12]. While traditional animal models continue to provide value in understanding whole-body systems, their role is becoming more targeted and judicious. The future of pharmacology research lies in integrated testing strategies that synergistically combine in silico, in vitro, and human-centric data [12]. This paradigm shift promises to enhance the predictive power of preclinical research, accelerate the development of safer therapeutics, and firmly align scientific progress with the highest ethical standards.

Frameworks in Action: Methodologies for Systematic Model Assessment

In pharmaceutical drug discovery, animal studies are a regulatory expectation for preclinical compound evaluation before progression into human clinical trials [29] [15]. However, the field faces a significant challenge: high rates of drug development attrition have prompted serious concerns regarding the predictive translatability of animal models to the clinic [29] [30] [15]. For instance, in acute ischaemic stroke research, only 3 out of 494 interventions showing positive effects in animal models demonstrated convincing effects in patients [30]. This translation gap represents not just scientific but also ethical and economic challenges, driving the need for systematic approaches to evaluate animal model relevance.

The Animal Model Quality Assessment (AMQA) emerges as a direct response to these challenges. Developed at GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), this structured tool provides a consistent framework for evaluating animal models to optimize their selection and application throughout the drug development continuum [15]. Unlike informal assessment approaches, AMQA offers a transparent, multidisciplinary methodology to reflect key model features and establish a clear connection between preclinical models and clinical intent, thereby rationalizing a model's usefulness for specific contexts of use [15].

Understanding AMQA: Development and Core Components

The Genesis of a Quality Assessment Tool

The AMQA tool originated from an internal after-action review at GSK that analyzed both successful and unsuccessful clinical assets to identify key points of misalignment between preclinical animal pharmacology studies and their corresponding clinical trials [15]. This investigation revealed several critical features that contribute to translational weaknesses, including fundamental understanding of the human disease, biological context of affected organ systems, historical experiences with pharmacologic responses, how well the model reflects human disease etiology and pathogenesis, and model replicability [15].

The tool evolved through three rounds of pilots and iterative design with input from various disciplines including in vivo scientists, pathologists, comparative medicine experts, and non-animal modelers [15]. This collaborative development ensured applicability across a broad portfolio of models, appropriateness for both well-characterized and novel models, and practical utility for researchers. The resulting framework addresses a recognized need in pharmacological research for more standardized approaches to model evaluation [15].

Key Assessment Domains and Workflow

The AMQA employs a question-based template that guides investigators through critical considerations for evaluating and justifying an animal model for a specific human disease interest [15]. This approach makes implicit assessments explicit, focusing on the relevant questions being asked in drug development. While the full questionnaire is detailed in the original publication, key assessment domains include:

- Human Disease Understanding: Evaluating the fundamental knowledge of human disease pathology and mechanisms.

- Biological/Physiological Context: Assessing the relevance of organ systems and physiological processes affected.

- Pharmacological Responsiveness: Reviewing historical experiences with drug responses in the model compared to humans.

- Etiological and Pathogenetic Alignment: Examining how well the model disease reflects human disease causes and progression.

- Replicability and Consistency: Determining the model's reliability across experiments and research settings.

The typical workflow for applying AMQA in pharmacological research involves multiple stages, as illustrated below:

The assessment culminates in a practical output that clearly identifies strengths and weaknesses of a model, providing insights that can guide model selection, highlight knowledge gaps requiring additional investigation, or suggest when alternative platforms might be more appropriate [15].

AMQA in Practice: Experimental Application and Protocol

Implementation Methodology

Implementing AMQA requires a systematic, collaborative approach with clearly defined protocols. The experimental application of AMQA involves several key phases:

Phase 1: Team Assembly and Scope Definition

- Convene a multidisciplinary team including in vivo scientists, laboratory animal veterinarians, pathologists, and clinical pharmacologists [15]

- Clearly define the context of use for the animal model within the drug development pipeline (e.g., target validation, efficacy testing, safety assessment) [31]

- Establish the specific human clinical condition of interest and key clinical endpoints to be modeled

Phase 2: Evidence Collection and Assessment

- Gather existing literature and historical data on the animal model's performance characteristics

- Collect internal experimental data from previous studies using the model

- Complete the AMQA question-based template through structured discussion and evidence review

Phase 3: Scoring and Interpretation

- Apply the high-level scoring system to evaluate predictive translatability

- Identify critical weaknesses that might limit clinical translation

- Develop mitigation strategies for identified weaknesses through model refinement or complementary approaches

A specific example documented in the literature demonstrates the application of AMQA to the adoptive T-cell transfer model of colitis as a mouse model to mimic inflammatory bowel disease in humans [15]. This published example provides researchers with a template for implementing the assessment in their own pharmacological research contexts.

Research Reagent Solutions for AMQA Implementation

The following table details essential materials and resources required for effective AMQA implementation in pharmacological research:

| Research Reagent Solution | Function in AMQA Implementation |

|---|---|

| Multidisciplinary Expert Team | Provides diverse perspectives on model relevance across scientific disciplines [15] |

| Historical Model Performance Data | Offers evidence-based insights into model consistency and pharmacological responsiveness [15] |

| Clinical Disease Characterization | Serves as reference standard for evaluating model alignment with human condition [15] |

| Pharmacological Response Database | Enables comparison of drug effects between model and human patients [15] |

| Standardized Assessment Template | Guides consistent evaluation process across different models and research teams [15] |

| Pathological Validation Tools | Provides objective measures of disease recapitulation at tissue and cellular levels [15] |

Comparative Analysis: AMQA Versus Alternative Assessment Approaches

Established Model Assessment Frameworks

While AMQA represents a comprehensive approach developed within the pharmaceutical industry, other frameworks exist for evaluating animal models in pharmacological research. The Framework to Identify Models of Disease (FIMD) includes factors to help interpret model similarity and evidence uncertainty [15]. Other approaches have suggested disease-specific functional deficit assessments [15] or incorporated various scoring systems to quantify model relevance [15].

What distinguishes AMQA is its specific development within a global pharmaceutical context and its direct focus on optimizing decision-making throughout the drug development pipeline. Unlike frameworks primarily designed for basic research, AMQA explicitly connects model assessment to clinical translation success, addressing the specific evidence needs for advancing compounds through preclinical development toward human trials [15].

Emerging Non-Animal Technologies (NAMs)

The landscape of preclinical assessment is rapidly evolving with the emergence of New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) that offer complementary or alternative approaches to traditional animal models. The following table compares AMQA with leading alternative assessment frameworks:

| Assessment Approach | Primary Focus | Key Strengths | Limitations in Pharmacology |

|---|---|---|---|

| Animal Model Quality Assessment (AMQA) | Evaluation of in vivo animal models for translational relevance [15] | • Industry-developed for drug development context• Structured, question-based approach• Multidisciplinary perspective• Direct line of sight to clinical intent | • Limited application to non-mammalian models• Requires significant expertise across disciplines• Less familiar in academic settings |

| Framework to Identify Models of Disease (FIMD) | Interpretation of model similarity and evidence uncertainty [15] | • Systematic evaluation of disease recapitulation• Considers multiple dimensions of model relevance | • Less specific to pharmacological context• Limited guidance on predictive translatability for drug response |

| New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) | Replacement, reduction, and refinement of animal use [31] [32] | • Human-relevant biology (organoids, organs-on-chips)• High-throughput capability• Reduced ethical concerns• Potential for human genetic diversity integration | • Limited regulatory acceptance for standalone use• Challenges with systemic disease modeling• Variable reproducibility between platforms• Often requires defined context of use [31] |

| Functional Deficit Assessment | Disease-specific functional outcomes [15] | • Focus on clinically relevant endpoints• Quantitative outcome measures | • Narrow scope limited to functional measures• May overlook pathological mechanisms |

The relationship between these assessment approaches and their applications across the drug development pipeline reveals distinct but complementary roles:

Quantitative Assessment: Performance Data and Validation Metrics

Impact on Decision-Making and Translation

While specific numerical outcomes of AMQA implementation are proprietary, the tool's value is demonstrated through its systematic approach to addressing key sources of translational failure in pharmacology. Quantitative analysis of historical translational challenges highlights the critical importance of rigorous model assessment:

| Translational Challenge Domain | Impact on Drug Development Success | AMQA Mitigation Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Biological Relevance | Species-specific differences in drug target homology limit predictive value for 100+ human-specific targets [31] | Structured assessment of target conservation and pharmacological responsiveness [15] |

| Disease Recapitulation | Fewer than 50% of animal studies sufficiently predict human outcomes in systematic reviews [30] | Evaluation of etiological and pathogenetic alignment with human disease [15] |

| Study Design Limitations | Underpowered animal studies (often with small group sizes) reduce reliability and reproducibility [30] | Consideration of model replicability and consistency in assessment [15] |

| Environmental Standardization | Overly strict standardization increases false-positive rates by 15-20% in some models [30] | Evaluation of model performance across varied experimental conditions [15] |

Integration with Complementary Assessment Methodologies

The most forward-looking application of AMQA involves its integration with emerging computational and AI-driven approaches. The AnimalGAN initiative developed by the FDA represents a complementary approach that uses generative AI to simulate animal study results and reduce reliance on animal testing [33]. In a pilot study, synthetic data from AnimalGAN for toxicogenomics, hematology, and clinical chemistry showed potential for use in toxicity assessments, mechanistic studies, and biomarker development similar to actual experimental data [33].

Furthermore, artificial intelligence and machine learning (AI/ML) approaches are increasingly being applied to enhance the assessment of model relevance and translation. AI/ML can help distinguish signal from noise in biological data, reduce data dimensionality, and automate the comparison of alternative mechanistic models [31]. The integration of these computational approaches with structured assessment tools like AMQA represents the future of model evaluation in pharmacology.

Future Directions: AMQA in the Evolving Preclinical Landscape

Integration with NAMs and Computational Approaches

The future of animal model assessment lies in integrated approaches that combine tools like AMQA with New Approach Methodologies and computational modeling. As recognized by regulatory agencies including the FDA, opportunities now exist to waive certain animal testing requirements, particularly for therapeutics targeting human-specific pathways, using NAMs that provide human-relevant data [31]. In this evolving landscape, AMQA can play a valuable role in determining when traditional animal models remain essential and when alternative approaches may provide superior predictive value.

Clinical pharmacologists are increasingly positioned to lead the integration of mechanistic models with AMQA assessments. Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models and quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP) approaches can translate in vitro NAM efficacy or toxicity data into predictions of clinical exposures, thereby informing first-in-human dose selection strategies [31]. These integrated approaches enable more robust decision-making in early drug development by combining human-relevant data from NAMs with structured assessment of traditional models through frameworks like AMQA.

Expanding Applications Beyond Model Selection

While initially developed to guide animal model selection, AMQA's potential applications continue to expand. The tool provides quality context for evidence derived from models to inform decision-makers at critical development milestones [15]. Additionally, AMQA can support harm-benefit analysis by institutional ethical review committees by providing a more rigorous assessment of potential scientific benefit than traditional justifications based primarily on citations of previous work [15].

As pharmacological research evolves toward more complex disease modeling and personalized medicine approaches, structured assessment tools like AMQA will become increasingly valuable for evaluating model fit-for-purpose across diverse therapeutic contexts. The transparency provided by such assessments helps research teams acknowledge and mitigate model limitations while maximizing the translational value of preclinical evidence in support of innovative medicines for patients.

In pharmacological research, selecting a disease model with high predictive validity for human responses is a critical, high-stakes decision. For decades, animal models have been the cornerstone of preclinical testing, yet they often fall short in predicting human safety and efficacy, contributing to the high failure rates of drugs in clinical trials [34]. The recent regulatory shift, exemplified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) 2025 roadmap to phase out animal testing requirements for monoclonal antibodies, underscores the urgent need for robust, human-relevant models [12] [16]. This transition is fueled by the recognition that traditional animal-based data have been poor predictors of drug success, particularly for complex conditions like cancer, Alzheimer's, and inflammatory diseases [16].

In this evolving landscape, the Framework to Identify Models of Disease (FIMD) emerges as a vital standardized scoring system. FIMD is designed to provide researchers with a quantitative, transparent methodology to evaluate and compare the utility of various disease models—from traditional animal systems to advanced New Approach Methodologies (NAMs) like organ-on-chip, in silico modeling, and complex in vitro models [31]. By establishing a common metric for model assessment, FIMD aims to enhance the reliability of preclinical data, streamline regulatory submissions, and accelerate the development of safer, more effective therapies.

FIMD Core Architecture: Components and Scoring Methodology

The FIMD scoring system is built on a multi-axis architecture that quantifies the strengths and limitations of each model across dimensions critical for pharmacological research. The framework generates a composite FIMD Score on a 100-point scale, enabling direct, objective comparison between disparate models.

Table 1: The Core Components of the FIMD Scoring System

| Component | Max Score | Description | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physiological Relevance | 30 | Assesses how well the model recapitulates key aspects of human disease biology and pathophysiology. | Target homology, disease phenotype recapitulation, multicellular interactions. |

| Predictive Validity | 25 | Measures the model's historical accuracy in predicting clinical efficacy and safety outcomes in humans. | Concordance with clinical trial results, safety liability identification. |

| Technical Robustness | 20 | Evaluates the model's reliability, reproducibility, and scalability. | Inter-laboratory variability, assay standardization, throughput. |

| Context-of-Use (CoU) Alignment | 15 | Scores the model's suitability for a specific research application (e.g., target validation, toxicity screening). | Defined CoU, regulatory acceptance for the intended purpose. |

| Operational Practicality | 10 | Assesses feasibility of implementation, including cost, timeline, and ethical considerations. | Cost-effectiveness, timeline, ethical compliance (3Rs). |

The FIMD Calculation Formula

The composite FIMD Score is a weighted sum of its components:

FIMD Score = (Physiological Relevance × 0.30) + (Predictive Validity × 0.25) + (Technical Robustness × 0.20) + (CoU Alignment × 0.15) + (Operational Practicality × 0.10)

Scores are categorized as: Excellent (85-100), Good (70-84), Moderate (55-69), and Poor (<55). This standardized score allows researchers to quickly gauge a model's overall utility and suitability for their specific project.

Quantitative Comparison of Disease Models Using FIMD

Applying the FIMD framework to common models used in drug development reveals their relative strengths and weaknesses. The following comparison highlights why a one-size-fits-all approach is often inadequate and how FIMD guides model selection based on the specific research context.

Table 2: FIMD Quantitative Comparison of Different Disease Models

| Model Type | Example Systems | FIMD Score | Key Strengths | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Human Primate (NHP) | Cynomolgus monkey | 78 (Good) | Whole-body physiology; complex immune system [31]. | High cost, ethical concerns, poor predictor for some immunotherapies (e.g., TGN1412) [31]. |

| Rodent Models | Transgenic mice, rat disease models | 65 (Moderate) | Genetic manipulability, established historical data, low cost. | Significant species-specific differences in pathophysiology and drug targets [31]. |

| Organ-on-a-Chip | Lung-on-a-chip, gut-on-a-chip | 82 (Good) | Human cells; replicates tissue-level function and mechanical forces; high human relevance [12]. | Limited multi-organ integration; model complexity can lead to variability [31]. |

| In Silico / QSP Models | PBPK, Quantitative Systems Pharmacology | 85 (Excellent) | High throughput; can simulate human populations and virtual trials; integrates diverse data sets [35]. | Dependent on quality of input data; can be a "black box"; requires computational expertise [35]. |

| Human Organoids | iPSC-derived brain, liver organoids | 80 (Good) | Human genetics; 3D structure captures some tissue complexity; patient-specific [12]. | Immaturity of cells; lack of vascularization and full immune component; reproducibility challenges [35]. |

The data shows that advanced NAMs like in silico and organ-on-a-chip models are achieving FIMD scores comparable to, and in some cases exceeding, traditional animal models. This quantitative justification underpins the regulatory and scientific shift towards these human-relevant approaches. However, the scores also clearly indicate that no single model is superior in all categories, emphasizing the need for a fit-for-purpose selection based on the defined Context-of-Use.

Experimental Protocols for FIMD Validation and Application

Protocol 1: Establishing Predictive Validity for Safety

This protocol is designed to quantify a model's accuracy in predicting human-relevant safety outcomes, a critical aspect of the Predictive Validity component in FIMD.

- Compound Selection: Curate a reference set of 20-30 compounds with well-characterized clinical safety profiles, including known safe drugs, drugs withdrawn for toxicity (e.g., liver toxicity), and benchmark biologics.

- Model Dosing & Exposure: Treat the model (e.g., liver-organoid, organ-on-chip) with the compounds at concentrations covering therapeutic and supra-therapeutic ranges. Include appropriate positive and negative controls.

- Endpoint Analysis: Measure a panel of high-content endpoints at multiple time points. These include:

- Cell Viability: ATP-based assays.

- Cellular Stress: High-content imaging for oxidative stress (ROS), mitochondrial membrane potential, and DNA damage markers.

- Secretory Profile: Multiplexed cytokine/chemokine release assay.

- Tissue Integrity: Transepithelial electrical resistance (TEER) for barrier models.

- Data Integration & Score Calculation: Use the resulting data to calculate a prediction model. The concordance between the model's prediction and the known human outcome is used to generate the Predictive Validity sub-score within FIMD.

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Physiological Relevance for Monoclonal Antibodies

This methodology supports the scoring of the Physiological Relevance component, particularly for models used to test mAbs, a primary focus of recent FDA guidance [12] [16].

- System Setup: Establish the model system, which could be a humanized mouse model (expressing the human drug target) or a NAM such as a PBMC-loaded organ-on-chip system or a 3D co-culture of human immune and target cells.

- Challenge with Reference mAbs: Treat the model with a panel of reference therapeutic mAbs. This panel should include:

- mAbs with known on-target, off-tissue toxicity in humans.

- mAbs with known cytokine release syndrome risk.

- mAbs with a clean clinical safety profile.

- Phenotypic Readouts: Quantify key pharmacological and toxicological responses:

- Efficacy: Target cell depletion (e.g., via flow cytometry) or modulation of a functional endpoint.

- Safety: Measure cytokine storm markers (e.g., IL-6, TNF-α, IFN-γ) and histological evidence of tissue damage.

- PK/PD Relationship: Model the exposure-response relationship if possible.

- FIMD Scoring: The model's ability to recapitulate the human-specific efficacy and safety phenotypes of the reference mAbs directly contributes to its Physiological Relevance score. A model that correctly identifies the risky and safe mAbs scores highly.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of FIMD and the execution of the described protocols rely on a set of key reagents and platforms. The selection of high-quality, well-characterized materials is fundamental to ensuring the reproducibility and reliability of the model validation data.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Platforms for Disease Model Validation

| Reagent/Platform | Function | Application in FIMD Context |

|---|---|---|

| Reference Compound Sets | A curated library of drugs with definitively known human efficacy and safety profiles. | Serves as the gold standard for experimentally determining a model's Predictive Validity score. |

| Human Primary Cells/iPSCs | Non-immortalized cells or induced pluripotent stem cells derived from human donors. | Forms the biological basis for human-relevant NAMs; critical for scoring Physiological Relevance. |

| High-Content Imaging Systems | Automated microscopy platforms for multiparametric analysis of cell morphology and function. | Quantifies complex phenotypic endpoints (e.g., cytotoxicity, oxidative stress) for Technical Robustness. |

| Multiplex Cytokine Assays | Bead- or ELISA-based kits to simultaneously quantify dozens of secreted proteins. | Measures critical immune and toxicity responses (e.g., cytokine release) for Safety Pharmacological Assessment. |

| AI/ML Analytics Platforms | Software utilizing artificial intelligence and machine learning to analyze complex datasets. | Integrates high-dimensional data from NAMs to generate predictive readouts and support Context-of-Use Alignment [31]. |

| Cianidanol | Cianidanol, CAS:8001-48-7, MF:C15H14O6, MW:290.27 g/mol | Chemical Reagent |

| Allocryptopine | Allocryptopine | Allocryptopine, a natural isoquinoline alkaloid. Key research applications include neuroprotection and anti-inflammation. For Research Use Only. Not for human use. |

The Framework to Identify Models of Disease (FIMD) provides the pharmacological research community with a critically needed tool for the systematic, quantitative evaluation of disease models. By moving beyond subjective preference and tradition, the standardized FIMD score brings objectivity to the model selection process. As the industry undergoes a foundational shift—driven by both regulatory push [16] and the scientific pull of more predictive human-based NAMs [12] [31]—the adoption of frameworks like FIMD will be essential. It empowers scientists to make informed, defensible decisions, ultimately enhancing the translational success of new drugs and ensuring that resources are invested in the most promising, human-relevant research avenues.

The transition of therapeutic interventions from controlled laboratory settings to effective clinical applications remains a significant challenge in biomedical research. External validity, defined as the extent to which research findings from one setting, population, or species can be reliably applied to others, stands as a critical determinant of successful translation [36]. In pharmacology research, this concept is particularly crucial when evaluating animal disease models, which must bridge the gap between experimental findings and human therapeutic applications. High rates of drug development attrition—with many programs discontinuing even in clinical Phase III—highlight the persistent difficulties in predicting human responses based on preclinical data [37] [38]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of frameworks and methodologies for assessing external validity, offering researchers structured approaches to evaluate the translational potential of their experimental models.

Fundamental Concepts: Defining Validity in Animal Models

The assessment of animal models for biomedical research has traditionally centered on three established validity criteria, originally proposed by Willner in 1984 and now widely accepted across research domains [5] [39]. These criteria provide a multidimensional framework for evaluating how effectively a model recapitulates critical aspects of human disease.

Table 1: Core Validity Criteria for Animal Model Assessment

| Validity Type | Definition | Research Question | Example Assessment Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predictive Validity | How well the model predicts unknown aspects of human disease or response to therapeutics [5] | Does response to known therapeutics in the model correlate with human clinical responses? | Testing established treatments in the model and comparing outcomes to human clinical data |

| Face Validity | How closely the model replicates the phenotypic manifestations and symptoms of the human disease [5] [39] | Does the model display key observable characteristics of the human condition? | Comparative analysis of behavioral, physiological, or biochemical markers against human disease presentation |

| Construct Validity | How accurately the model reflects the underlying biological mechanisms and etiology of the human disease [5] [39] | Does the disease in the model share the same fundamental biological basis as the human condition? | Genetic, molecular, and pathway analysis to compare disease mechanisms between model and human |

These three criteria are not mutually exclusive, and a comprehensive validation strategy should address all dimensions. However, it is important to recognize that no single animal model perfectly fulfills all validity criteria, necessitating careful model selection based on research objectives and often requiring complementary approaches using multiple models [5] [15].

Figure 1: Multidimensional Framework for Assessing Animal Model Validity

Quantitative Assessment Frameworks: Structured Tools for Validity Evaluation

The Animal Model Quality Assessment (AMQA) Tool

Developed by GlaxoSmithKline to address translational challenges in drug development, the AMQA tool provides a structured question-based framework for evaluating animal models [15]. This approach emphasizes multidisciplinary collaboration between researchers, veterinarians, and pathologists to transparently assess a model's strengths and weaknesses. The assessment covers multiple dimensions, including: the fundamental understanding of the human disease; biological and physiological context; historical data on pharmacological responses in the model; how well the model reflects human disease etiology and progression; and the model's replicability and consistency [15]. The output facilitates informed decision-making about model selection and helps identify potential translational weaknesses before committing significant resources.

Framework to Identify Models of Disease (FIMD)

The FIMD represents a more recent approach designed to systematically evaluate various aspects of external validity in an integrated manner [38]. This framework was developed through a scoping review that identified eight key domains critical for model validation: etiology and pathogenesis, genetic basis, symptoms and clinical presentation, histopathology and morphology, biomarkers, comorbidities, disease progression, and response to treatment [38]. Unlike earlier approaches that relied heavily on researcher interpretation, FIMD provides a standardized scoring system that enables scientifically relevant comparisons between different models. This systematic approach helps researchers select the most appropriate model for demonstrating drug efficacy based on specific mechanisms of action and indications.

Table 2: Comparison of Structured Assessment Frameworks for External Validity

| Framework | Primary Focus | Key Features | Output | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AMQA Tool [15] | Translational relevance for drug development | Question-based template, multidisciplinary input, transparent weakness identification | Qualitative assessment with identified gaps | Model selection, ethical review support, decision-making context |

| FIMD [38] | Efficacy model validation for specific indications | Eight-domain structure, standardized scoring, integrated validation | Quantitative scores enabling model comparison | Optimal model identification for specific drug mechanisms |

| Three Criteria Framework [5] [39] | General model evaluation | Established validity concepts (predictive, face, construct) | Categorical validation assessment | Initial model screening, educational contexts |

Experimental Protocols for Assessing External Validity

A Priori vs. A Posteriori Generalizability Assessment

In clinical trial design and translation, generalizability assessment methods can be categorized based on when the evaluation occurs relative to trial completion [40]. A priori generalizability (also called eligibility-driven) evaluates the representativeness of the eligible study population to the target population before a trial begins, using data from study eligibility criteria and observational cohorts [40]. This approach provides investigators the opportunity to adjust study design before trial initiation, potentially improving future generalizability. In contrast, a posteriori generalizability (or sample-driven) assesses the representativeness of enrolled participants to the target population after trial completion [40]. Despite the advantages of a priori assessment, fewer than 40% of published studies utilize this approach, representing a significant missed opportunity for improving translational research [40].

Benchmarking Against Simple Models

In quantitative systems pharmacology (QSP), where complex mechanistic models integrate knowledge of physiology, disease, and drug effects, assessing predictive performance against simpler models provides a valuable validation approach [41]. This methodology involves developing simplified versions of complex models through techniques such as focusing on steady states, lumping compartments, and using approximations. The QSP model's predictions are then systematically compared against those generated by the simpler models. This benchmarking approach helps identify when added complexity genuinely improves predictive capability versus when it merely leads to overfitting of noise in the data [41]. Examples where this approach has proven valuable include cardiotoxicity prediction, where simple models of ion channel block sometimes outperformed complex biophysical models, and oncology drug combinations, where simple probabilistic models have successfully predicted combination responses [41].

Figure 2: Workflow for Benchmarking Complex Models Against Simpler Alternatives

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Validity Assessment

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Validity Assessment | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Genetically Engineered Models [5] [15] | Recapitulate specific genetic aspects of human diseases | Construct validity assessment for diseases with known genetic components |

| Disease Induction Compounds (e.g., MPTP, 6-OHDA) [5] | Create disease phenotypes in animal models | Face validity establishment for neurological disorders |